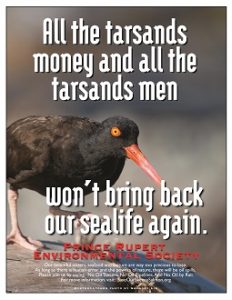

The Black Oystercatcher is a Keystone Species in the Pacific North West (Tessler 2007). The late Robert T. Paine coined the phrase “keystone species” back in 1969, as a species which has a disproportionately large affect on its environment in comparison to its abundance. With roughly 10,000 individuals from Alaska to Mexico, the Black Oystercatcher fits the bill, as its removal from an area will result in a trophic cascade that negatively impacts biodiversity. It has been recently noted that the bird is also thought to be a sentinel species, meaning that it is a strong indicator of the environmental integrity of the intertidal community, due to their sensitivity to environmental contaminants entering their food sources (Tessler 2007).

The populations of Black Oystercatchers appear to be regulated by their availability of quality nesting sites as well as healthy foraging habitat. This means that they are particularly sensitive to both natural, as well as human disturbances, and I’m sure you can guess which affects their populations more. Vessel wakes at high tide can soak nests and kill young, habitat is often encroached by oceanfront houses, nests are trampled, exotic predators can introduced, and Pollution like oil spills and industrial waste can cause a complete breakdown of the intertidal community on which these birds depend (Tessler 2007).

It’s not hard to imagine how something as simple as wake from a large boat could disrupt this nesting site.

The real value in using the Black Oystercatcher as a sentinel species, is that scientists can gauge the health of the intertidal community following a disaster of some sort. This is accomplished by observing the presence and survival of these birds and their chicks. During events like the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989, Black Oystercatchers are often extirpated from an area, and return of Oystercatchers into the area will often signal to naturalists that prey has not only returned to the area, but that it is no longer dangerously toxic (Tessler 2007)!

On the other side of the coin, When Oystercatchers are removed from an area due to nesting habitat loss, it has major ramifications on the intertidal ecosystem. Because Black Oystercatchers feed on grazers, such as limpets and snails, the removal of these birds from an ecosystem allows nearly unchecked growth by the grazers, which means that the algae on which they graze are nearly completely removed from the area. This means a lack of food for other creatures who depend on small bits of particulate matter, as well as loss of breeding and nesting habitat for many smaller invertebrates and fishes (Robinson 2016). This bird plays a key role in the health of our marine ecosystems, and it is no wonder that environmental groups along the coast are pushing for closer studies into all sorts of aspects of the Black Oystercatchers lifestyle, in an effort to gain more baseline data.

For all these reasons, this species is listed as a species of high concern within the United States and Canada, and is a part of Pacific shorebird conservation plans. The Black Oystercatcher is on the Audubon Society’s watch list, and was listed as a Bird of Conservation Concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Tessler 2007). It is good to know that our governments are keeping an eye on the Black Oystercatcher, but we as citizens need to be aware as well. That includes supporting habitat protection programs and keeping points of potential oil spills out of our waters. If this sounds like something you are interested in, check out this link and sign the petition! https://dogwoodbc.ca/campaigns/no-tankers/

References:

Paine, R. T. 1969. A note on trophic complexity and community stability. The American Naturalist 103: 91-93. Retrieved October 22, 2017 from https://doi.org/10.1086/282586

Robinson, B. H. 2016. Feeding ecology of Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) chicks. University of Alaska Fairbanks. Masters Thesis. Retrieved on October 22, 2017 from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1786926216

Tessler, D. F., Johnson, J. A., Andres, B. A., Thomas, S., & Lanctot, R. B. 2007. Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) conservation action plan. International Black Oystercatcher Working Group, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Anchorage, Alaska, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska, and Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences, Manomet, Massachusetts. Retrieved October 18, 2017 from http://www.whsrn.org/shorebirds/conservation_plans.html

Very informative blog post Brain! I had no idea that the Black Oystercatchers are considered a keystone and sentinel species. I found the photo you included of their nesting site (photo #2) to be quite surprising! I wasn’t aware that they basically lay their eggs on a pile of rocks. It was mentioned that oystercatcher populations are typically limited by the availability of quality nesting sites. What is considered to be a quality site for these birds, and are they heavily predated on while being so “out in the open”?

Hi Brian, not sure why my comment showed up as anonymous! Just thought I’d let you know this is Chanelle 🙂

Hey Chanelle, thanks for the feedback! The picture with the eggs on a pile of rocks is actually a good example of what can happen when nesting sites are limited. Generally, a black oystercatcher will lay its eggs in grass above the high tide mark, and the eggs are speckled brown for camouflage. Not only are the eggs on the rocks more open to predation, but they stand a higher chance of breaking and/or being taken by waves in a storm event. The other extreme would be a nesting site further from the shoreline where the parents have to spend more time away from a nest getting food, and as they grow, the chicks must travel farther as well, which increases the chances of predation. Thanks for your question!

Hi Brian,

Like Chanelle said, I also didn’t know that BLOYs are a keystone species or used a sentinel of marine ecosystem health. I love reading these blogs because these are the types of tidbits that are important to share with others to help increase awareness of our local natural history and how to help care for important creatures like the Black Oystercatchers! Side note: yet another cool species that relies on an intact marine ecosystem, free of oil spills! Thanks for pointing that out.

-Hannah

Very interesting Brian. Has the effect of BLOY as a keystone species been found to be as strong / evident as for the purple sea star? VIU Biology grad did her 491 project on BLOY foarging on varnish clams (http://bit.ly/2iKvAS3). It’s amazing how they adapted well to this introduced species, and they make quick work of them.