Identification

Introducing the Surf Scoter or Melanitta perspicillata, this goofy-looking waterfowl earned his endearing nickname “Old Skunkhead” with the black and white patches of his head. (Cornell University: All about birds) They fall under the common name of the duck family, however, their correct family name is Anatidae. This little weirdo is easy to ID. With an unmistakeable marking that almost looks like it has a giant third eye at the base of their sloping orange bill they really can’t be missed. When differentiating between the females and males, as in most bird species, we look for the duller colours in females including a less haunting orange and white bill. when ID’ing solo females you want to look for two white patches on her head as well as the sloping beak with a grey, less eyeball looking, marking at the base.

Life as a Scoter

These birds are ground nesters that will nest and rear their chicks near lakes of northern Canada and Alaska. (Cornell: All About Birds) Scoters will find their mates during winter months when the males perform their courtship dance. Males will hold a stiff neck, periodically dipping their beak into the water and preening themselves. They may also do short bursts of almost flights out of the water landing near the female and calling out. If she is impressed by his moves, she will give a “chin-lift” behaviour and all, and then the wedding bells are ringing. Lastly, the male will raise his tail, shake his head and turn away to show off his handsome white patches. (Cornell: All About Birds) When its time for scoters to make their nests they will do so and hide it under vegetation to protect their eggs or fledglings. They create the classic nest bowl that we see in children’s books and cartoons. (Cornell: All About Birds) Then they spend the rest of their life cycle floating around the Atlantic and Pacific ocean coasts looking for aquatic vegetation and hunting benthic prey. (Ydenberg & Schenkeveld, 1895) Benthic prey being a fancy term for creatures that live at the bottom of the ocean floor. They too enjoy the delicacies of clams, mussels, and escargot, but will also munch on marine worms, hydrozoans (a cousin of the jellyfish) and aquatic vegetation. (Cornell: All About Birds)

True Diving Ducks

Surf Scoters will synchronously dive for food, meaning they will dive down and come back up in patterned groups. There are a few hypotheses as to why they do this. One being strength in numbers, they are often more successful and can corner more prey this way. It is also a good way to protect themselves from oncoming predators or pests. (Ydenberg & Schenkeveld, 1895). There have been sightings and reports of “non-foraging” dives. This is described as social behaviour, Scoters will form a group and synchronously dive just for the practice, mastering their routines for the next Olympics perhaps? They will also bring in reinforcement by adding more scoters to these impressive diving routines when pesky gulls are around to try and interfere with their hunt. (Ydenberg & Schenkeveld, 1895) Gulls are known to steal swipe the catches from scoters as they surface from a dive. (Ydenberg & Schenkeveld, 1895) I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, no one likes the gulls. Those little kleptomaniacs have prompted researchers to form the klepto-parasitism hypothesis, which they think is a part of the reason why Scoters (and other seabirds) synchronously dive. (Ydenberg & Schenkeveld, 1895) Kleptoparasitism is simply the act of food theft. (Gaglio et. al, 2018) Kleptoparasitism can have a huge effect on Surf Scoters as they get most of their daily food needs from a single mussel. If that mussel is robbed, they have spent a great deal of their energy on a wasted dive. (Ydenberg & Schenkeveld, 1895) There have been recordings of some huge groupings of scoters diving together. Have a look, this next video gets interesting at about 0:45.

How neat is that….

Surf Scoter’s and Telemetry

Surf Scoters play a large roll in a telemetry study with the Canadian Wildlife Cooperative, proving that I am not the only one who thinks these birds are pretty neat. (Net, et. al, 2019) Telemetry uses satellite transmitters to track things such as (but not limited to) ecology, population density and migration patterns of a specific species of bird. In diving ducks, researchers have found more success using an intracoelomic transmitter with an external antenna. This involves surgically implanting the transmitter into the coelom (internal body cavity). While this is more invasive than the external transmitters used in many bird species are monitored with telemetry, it has proven to prevent complications in the long term. (Mills et. al, 2016) Look at that little swimming car radio go, contributing to science and stuff.

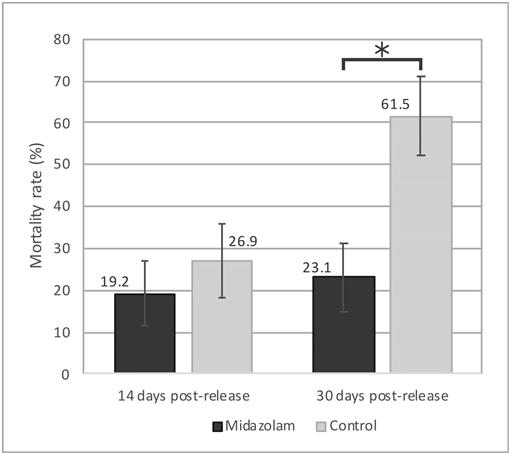

While these transmitters have been relatively safe for most diving ducks, they seemed to be posing a threat to our precious Surf Scoters. The mortality rate of other diving ducts was found to be 0-10% mortality after implantation, while Surf Scoters saw a 61% mortality rate. (Net et. al, 2019) The difference is staggering and it prompted a study by R. L. Net and his colleges, that searched for a way to reduce this. These numbers become even more embarrassing for our favourite water birds as they found that the main (but not only) culprit for the post-implantation mortality was due to stress. The stress of being taken away from their natural habit and handled is too much for our fragile little friends. Even though other diving birds handled the implantation process just fine, our especially sheltered waterfowl friends could not handle it. So to take away some of the stress they designed an experiment in which they sedated the Scoters, which I’m sure we all could benefit from sometimes.

The birds were captured in floating mist nests, a commonly used tool in many avian-based research and studies. (Net et. al, 2019) The sedative Midazolam Hydrochloride was then given shortly after their initial capture and shortly before returning back to the ocean, they then monitored their survival using the freshly placed transmitters. (Net et. al, 2019) The experiment monitored 56 female birds from time captured to surgical implantation, to recovery and release(Net et. al, 2019). Why did they choose to only perform this experiment on female scoters? I’m not entirely sure, my guess was to keep the experiment as controlled as possible. They gave 28 birds the Midazolam intranasally and 28 birds saline intranasally as a control. they used a soft-tipped catheter tip to inject the medication or placebo safely into the nostrils of the birds. This is more of a glorified squirt gun if you ask me. One of the perks of Midazolam is that it is highly effective and fast-acting when given intranasally, which reduces the handling time and stress of the bird further. (Mans, et. al 2012) Once they released our funky flying friends, the results came back extremely positive.

They saw a huge drop in the mortality rate when using the sedative post-implantation. They check in with the birds at 14 days and 30 days post-release. (Net et. al, 2019) The final results showing that the group of birds that did not receive the Midazolam had a mortality rate of 61.5%, as expected, while the birds treated with the drug only saw a mortality rate of 23.1%. (Net et. al, 2019) Excellent news for future scoters that are used in Telemetry.

Thanks for reading! Please feel free to ask any questions in the reply section below.

References

Gaglio, D., Sherley, R. B., Cook, T. R., Ryan, P. G., & Flower, T. (2018). The costs of kleptoparasitism: a study of mixed-species seabird breeding colonies. Behavioral ecology, 29(4), 939-947.

Mans, C., Guzman, D. S.-M., Lahner, L. L., Paul-Murphy, J., & Sladky, K. K. (2012). Sedation and Physiologic Response to Manual Restraint After Intranasal Administration of Midazolam in Hispaniolan Amazon Parrots (Amazona ventralis). Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery, 26(3), 130–139. doi: 10.1647/2011-037r.1

Mills, K. L., Gaydos, J. K., Fiorello, C. V., Whitmer, E. R., De La Cruz, S., Mulcahy, D. M., … & Ziccardi, M. H. (2016). Post-release survival and movement of western grebes (Aechmophorus occidentalis) implanted with intracoelomic satellite transmitters. Waterbirds, 39(2), 175-187.

Net, R. L., Mulcahy, D. M., Santamaria-Bouvier, A., Gilliland, S. G., Bowman, T. D., Lepage, C., & Lair, S. (2019). intranasal administration of midazolam hydrochloride improves survival in female surf scoters (melanitta perspicillata ) surgically implanted with intracoelomic transmitters. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine : Official Publication of the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians, 50(1), 167. doi:10.1638/2018-0115

Surf Scoter Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Surf_Scoter/overview.

Ydenberg, R. C., & Schenkeveld, L. E. (1985). Synchronous diving by surf scoter flocks. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 63(11), 2516-2519. doi:10.1139/z85-372

Hi Em,

Nice blog:) These adorable sea birds are so fun to watch, thank you for including some great videos to highlight their neat behaviour! I have been lucky enough to see those massive rafts of Surf Scoters, and it kind of looks like a Where’s Waldo game to find the treasures hidden among the scoters!

The research you chose on Surf Scoter telemetry was interesting. It seems like a very invasive method to be tracking these birds. You mention that researchers have found more success in diving ducks using an intracoelomic transmitter with an external antenna, do you know why that is? Do other transmitters just fall off a lot easier? It’s very sad that there is a 61% rate of mortality for Surf Scoters with these transmitters. Did the paper suggest any other methods to reduce this aside from sedatives? Even a 23% rate of mortality after sedatives seems too high. Imagine if bird research on passerines was the same – that would be heartbreaking. We talk about replacement, reduction, and refinement in animal research, so one would think that these researchers could think of a better way of tracking Surf Scoters. In this situation, it seems to me that ends might not justify the means.

Thanks for sharing your love of scoters!

Samuelle

Hi Samuelle!

Thanks for your comment!

They avoid using external transmitters as they actually found them to be more threatening to the birds. The external transmitters caused changes in their maintenance behaviours (preening), as well as thermoregulation, and hydrodynamic drag when they are diving/trying to hunt. So while surgical implantation is far more invasive up front, it serves to be safer in the long run.

I agree the statistics don’t seem to support using Scoters as Telemetry subjects, my hope is that this is just the beginnings of their efforts to decrease the mortality rates. I would think that any ethics board would have a problem with these current numbers.

Nicely layed out and informative blog! I now want to go out and find some of these cuties to photograph!

Thank you Kim! Last I saw some Surf Scoters was at the Englishman River Estuary in Parksville, but I’m sure you could see some around Victoria as long as you have a good view of the ocean.

Hi Em,

Nice blog! I also love surf scoters, such a unique looking bird.

You mentioned that their way of diving in groups may reduce predation (i.e. safety in numbers). What are some predators of the surf scoter that would capture them while diving?

Also, for the transmitter research using a sedative, you said the sedative was given to the scoters “shortly before returning back to the ocean”. Did the study mention anything about this affecting their ability to evade predators and forage? Wouldn’t it be more effective to give the scoters the sedative immediately after the surgery and then let the sedative get mostly out of their systems before release?

Hey Olivia! Thank you for reading my blog!! I actually noticed an error in my blog thanks to one of your questions.

When it came to administering the Midazolam they gave it to them both at the time of initial capture (which I missed in my initial blog post) as well as shortly before returning to the water. My understanding of this is that the point of the sedative was to calm the birds during any handling done by the researchers which is mostly right when they get out of the water and as they return them. So it seems to me that it would make the most sense to give it to them at those times. I can note that most veterinarians would likely not give sedatives immediately after surgery as they want to allow the animal to wake up from the anesthetic and make sure they have healthy vitals post-op. I wouldn’t think it affects their foraging or swimming abilities as the mortality rate did drop significantly, but given the nature of the tracking, there was no way to watch their specific behaviour.

When it comes to their diving the few articles I read on them never mentioned specific predators, unfortunately, I tried to do some research further research to answer your question and the only specific example I could find was Raptors. Bald Eagles and Peregrin Falcons were the two that were listed.

Thank you again!

Em

Hi Em.

Thank you for writing this hip cool & up-to-date article! I really enjoyed it. I’m surprised there was a surgical implantation of transmitters for tracking birds. And I was further surprised that mortality was due to the stress, not the surgery itself. I loved the videos you chose too! The sync swimming, males swimming like wind-up boat to impress the females definitely made me laugh of cuteness!

I’m curious, how do the researchers catch Surf Scooters for attaching the transmitters? They can fly and dive and often are seen offshore, do these factors make this bird a difficult bird catch?

Hideki

Hey Hideki!

Thank you so much for taking the time to read my blog I’m glad you enjoyed it. The scoters were captured in floating mist nests, similar to the ones we use while banding with VIU. I would think that their sneaky habits would make it a little difficult to capture them, which may also contribute to their stress levels, I think this is why they gave the sedative immediately after capture as well as before being returned.

Hope this answers your question!

Thank you again!

Hi Em,

Definitely the most entertaining blog I’ve read so far. You have a great way of keeping me interested through the entire thing!

My question is about the synchronized diving. It is so impressive! I am mostly wondering about the mechanism that produces this synchronicity. How do they all know to dive at a specific moment? I thought maybe a sort of domino mechanism but it seems that huge groups dive completely simultaneously! Perhaps a call or signal of some kind to warn of a near predator? Just wondering if you came about any information on that during your research.

Thanks!

Emma

Hi Emma!!

That is a great question, I haven’t been able to find anything specifically on the exact mechanism in place, however, I would assume that the birds all pay attention to each other’s behaviours and notice when their fellow floating pals are about to dive. The domino effect is strategic, the point of it is to avoid kelpto-parasitism from other gulls that “cherry-pick” their catches, as well as to defend from any predators. Having some birds remain floating while others dive avoids both of these.

I hope this clears things up a little!

Em

Hi Em,

Great job, this was a really entertaining and interesting read! Sadly, I didn’t even know Surf Scoters existed before I took this class so it has been wonderful to learn more about them! Like many others I am fascinated by the communication and social dynamics of birds that perform massive synchronized moves like those dives.

I was just wondering if you came across anything about how their senses function when they are underwater? We learned about how birds have excellent eyesight, and many oceanic birds use their sense of smell to locate food, since these ducks dive for prey and do it in such a synchronized way, do they have any adaptations to their eyes (or other senses) that might help to sense prey and other birds while they are swimming underwater?

Thanks !

Ally

Hey Ally!

I’m glad you enjoyed the blog!! I looked into your question and I haven’t found any adaptations to the eyes specifically, I found an article that discussed the hearing abilities of diving ducks that stated they trained birds to respond to auditory stimuli and reported their range of hearing to be from 1.0–3.0 kHz. Unfortunately, this was the best I could come up with for your question. All the other articles I found predominantly discussed changes in their foraging behaviour based on prey density. I read an article that monitored their behaviour changes when food sources were low, they relied less on diving and more onshore combing for clams or other Bivalves. While interesting, unfortunately, they do not really answer your question.

Great question! Sorry I couldn’t be of more help!

Em