INTRODUCTION

White-crowned Sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys) are a common species found here on the west coast of North America. These charming little birds are regular visitors to our yards and bird feeders, and their melodious song is often the background music to our springtime outings. Their bold, black and white heads allow the adults of this species to be readily identified, and they often seem perfectly comfortable to continue their activities as we look on from a short distance away.

The qualities of these sparrows have not gone unnoticed, in fact, they have been catching the attention of people for centuries! Its conspicuous nature, as well as its wide range and ability to thrive in captivity (Cornell Lab of Ornithology) have made it so attractive to ornithologists that White-crowned Sparrows have been referred to as the “white rat of ornithology” (Hultsch and Todt, 2004). Their songs in particular have been well studied and a great deal of what we know about birdsong development and modification has come from this species (Cornell Lab of Ornithology).

IDENTIFICATIION

White-crowned sparrows prefer habitats with low shrubs and grasses like meadows and forest edges where they can hop around on the ground looking for seeds, vegetable matter and insects to feed on. (Cornell University: All About Birds) They are on the larger end of the sparrow family (Passerellidae), weighing in at about 27 grams, with a body length of 17 cm and a wingspan of 24 cm (Sibley, 2016). Their bellies are a pale grey with brown flanks, and their wings have white bars with a pattern of brownish stripes, characteristic of many sparrows. Of course their most notable feature, the distinctive crown of black and white stripes, is the what lends these birds their name (Canadian Wildlife Federation).

As is the case with many sparrows, male and female White-crowned are mostly indistinguishable. Only subtle differences can be observed with a trained eye during the breeding season. Males are slightly brighter, and their dark supercilium (black stripe that extends from the eye to the back of the head) is clearer than their female counterparts. Male birds also tend to raise their crests (crown feathers) more than females do, often making the stripes appear broader, and their heads more squared (Sibley Guides).

Fledgling White-crowned Sparrows start out with stripey brown plumage so they can blend in with their surroundings. In their first fall they lose most of the stripes on their belly and look similar to adults, aside from lacking the distinct black and white head which they don’t gain until the following spring (BirdWeb). If you ever spot a sparrow with a grey belly and a crown of brown and tan stripes during the winter, you can identify it as a White-crowned Sparrow born that same year. The oldest White-crowned Sparrow ever recorded was just over 13 years (Cornell University: All About Birds).

HYBRIDIZATION

White-crowned Sparrows are also known to interbreed with other sparrows they are closely related to in areas where their ranges overlap (Sibley Guides). These hybrid birds will usually have some features of each species (try to pick these out in the photos below). On the west coast of BC, Golden-crowned x White-crowned Sparrows have been observed.

NESTING BEHAVIOUR

White-crowned Sparrow nests are made of grass, twigs, moss, bark and dead leaves. Resembling little cups, the nests are made comfortable with the addition of animal hair, feathers and soft grasses (Audubon). Female birds build the nests, lay four to five small greenish eggs dotted with reddish-brown spots, and incubate them for about twelve days. The males help to feed insects to the young birds soon after they have hatched up until they leave the nest seven to twelve days later. This process is repeated one or two more times for some populations, with White-crowned Sparrows that breed in the far South often raising up to 4 broods each year (Audubon).

DISTRIBUTION

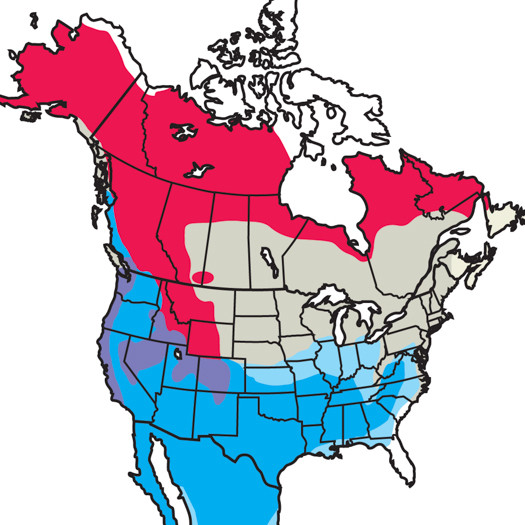

There are five recognized subspecies of White-crowned Sparrow: the Eastern Taiga, Western Taiga, Interior Western, Pacific (also known as Nuttall’s), and Puget Sound (Sibley Guides). All five have only subtle differences in colouration, although the Pacific groups (which include the Puget Sound subspecies) are distinctive in having a brighter yellow bill and fainter white head stripes than other populations (Cornell University: All About Birds). These west coast subspecies do not migrate and are year round residents, ranging from Vancouver Island to Southern California (Audubon).

Range of the White-Crowned Sparrow (Figure from Audubon).

- Red – breeding range

- Blue – winter range

- Grey – migration

- Purple – Year round residents

Although most people cannot tell them apart, in parts of North America it’s not uncommon for more than one subspecies to be in the same location during different times of the year (Sibley Guides). The migratory behaviour of Interior and Eastern White-crowned Sparrows varies considerably with some birds travelling short distances, and others flying thousands of kilometres from Alaska all the way to the Southern United States and back each year (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)!

Unlike other sparrows that prefer to travel in mixed flocks, the White-crowned migrates alone or with small numbers of its own species (Canadian Wildlife Federation). This strategy seems to work well for them as a lonely White-crowned sparrow was once tracked travelling 300 miles over one night (Cornell University: All About Birds)!

WHITE-CROWNED SPARROWS AS EXPERIMENTAL SUBJECTS

SONGS

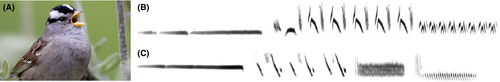

In White-crowned Sparrows, males are the usual vocalists, using their song to attract mates or uphold territory, but females may also sing to defend their resources (Cornell University: All About Birds). These sparrows are song learners, which means their songs are not innate, but must be learned from the local adults of their own species. This, and because adults often return to breed near to where they themselves were born, creates regional song variations or “dialects”. Birds that live on the edge of two areas have been known vary their song in order to be “bilingual”, and can sing and recognize both variations (Cornell University: All About Birds).

(video by Woodfibrebirder).

This interesting phenomenon has made these otherwise ordinary little sparrows the subject of ongoing study regarding the evolutionary history and significance of their songs. (Toews, 2017)

In 2017, research into song recognition was conducted on the Nuttall’s and Puget Sound subspecies. As male birds often use their voices to claim and defend territories, hearing another males song can illicit an aggressive response if they are thought to be competitor. In the study, recordings were made of the two subspecies’ songs and they were played for male White-crowned Sparrows of both subspecies in the wild. It was found that males responded more aggressively to the song of their own subspecies, and bilingual males that lived between ranges were aggressive to both songs (Lipshutz et al, 2016). This suggests that while there are still some birds that can interbreed between the two groups, primarily, males only consider those belonging to their own subspecies to be competitors for mates and resources. These findings indicate that song variation can be an important mechanism of reproductive isolation between subspecies (Toews, 2017).

(photo by Samuelle Simard-Provençal)

More research is still needed to determine how these song dialects develop and are used in populations, especially across smaller regions (Toews, 2017). For instance, on the Reyes peninsula in California, six separate song dialects were determined in a population of Nuttall’s White-crowned sparrows within an area of only 300 square kilometers. Interestingly, this data, combined with genetic analyses, can be very useful in establishing a timeline of when certain groups of birds became isolated, and how long ago they were reintroduced to each other (Lipshutz et al, 2016).

PESTICIDE EXPOSURE AND MIGRATION

White-crowned Sparrows are still living up to their nickname as the “white rats of ornithology” (Hultsch and Todt, 2004). A recent study used these birds to test the effects of exposure to a neonicotinoid pesticide on their migratory behaviour. Neonicotinoids are a class of insecticides known to be toxic to wildlife. Despite this, they continue to be used worldwide because of their low cost and convenience (Liao, 2019). Seed eating birds will often ingest crop seeds coated with these toxins (Eng et al, 2019).

In the study, White-crowned Sparrows were captured at a fall migratory stopover location in Northern Ontario. Over six hours they were exposed to varying doses of a neonicotinoid called imidacloprid (commonly used on Canadian farmland) at levels they would encounter in the wild. They were weighed (before and after exposure), measured, fitted with lightweight radio transmitters and released back into the wild to continue their journey (Liao, 2019).

Imidacloprid was found to be very harmful. The birds with high exposure (10% of a predicted lethal dose) lost weight at an extreme rate – almost 6% of their body weight in only six hours! Even exposure to low levels (3% of a predicted lethal dose) caused a delay in migration of up to 2.5 days, as the sparrows had to recover their appetite and replace their fat stores before continuing migration (Eng et al, 2019). This extra time spent at stopover locations can increase the risk of predation, and impede reproduction if effected birds arrive late to their breeding grounds (Liao, 2019). Since imidacloprid and other neonicotinoids are used all across North America, repeated exposure over the course of a migration could be very detrimental to certain populations (Eng et al, 2019). These findings highlight the need for revisions to agriculture practices that depend on chemical insecticides, such as the commercial production of monoculture crops (Liao, 2019).

Although White-crowned Sparrows are considered to have a stable population and be a species of least concern (Cornell University: All About Birds), others have not been so lucky. Grassland birds, which include many fellow species of sparrow, have seen the worst reduction in numbers across all ecosystems- losing 53% of their total population since 1970, with 74% of grassland bird species still in decline (Rosenburg et al, 2019). Research into the causes of such devastating losses, like the prolonged of toxic pesticides as mentioned above, is essential. White-crowned Sparrows have been representing Class Aves in scientific experiments since 1772 (Cornell Lab of Ornithology), providing unique insight into the extraordinary lives of the birds around us. Today, they continue to be the valuable test subjects of studies working toward the protection and enhancement of their avian communities.

Hi Ally,

Lovely informative blog. The White-crowned Sparrow is a very pretty bird, and has clearly served researchers well over the years. It’s a shame we don’t catch more at Buttertubs! The first winter birds are great for ageing… I guess you could call it “slap in the face body plumage!” 😉

I like your bit on hybridization, I always find this topic so intriguing. You mentioned instances of Golden-crowned Sparrow x White-crowned Sparrow and Harris’s Sparrow x White-crowned sparrow (very cool!). Did you at all come across anything on hybrids with other Zonotrichia sparrows (White-throated Sparrow or Rufous-collared Sparrow – although the later I guess would have limited (if at all) range overlap with the White-crowned Sparrow).

Thank you for sharing your love of these lovely sparrows!

Samuelle

Hi Sam,

I am fascinated by the sparrow hybridization too! There is so much information on White-crowned Sparrow subspecies hybrids, but very little I could find on hybrids they form with other species. GCSP x WCSP seem to be the most commonly seen and photographed, the WTSP x WCSP are also fairly common and the HASP x WCSP seems to be the least. I only came across two people who had photographs recorded of Harris’ x White-crowned Sparrow hybrids.

Interestingly, the interactive map on eBird shows the only two locations where HASP x WCSP sightings have been reported are a small area in Wisconsin and a small area in Minnesota. The range of the other two hybrid sightings seems to be much more widespread.

I haven’t been able to find any mention of a hybrid between the White-crowned and Rufous-collared Sparrows. As you suggested they might be a little too far south for much interaction between those species. I bet it the result would be a really beautiful sparrow if that cross ever did happen!

Perhaps we will get lucky and see (or catch!) a hybrid sparrow at Buttertubs one day!

Thanks for your interest!

Hi Ally.

It’s such an interesting article! I did not know there were bilingual White-Crowned Sparrows among the populations and mate/rival recognition by dialects. Also this article gave me for the first time the realization of how fast and significant the common pesticides affect birds. The 6% body weight decease in six hours sounds pretty serious… and how it indirectly deceases the bird’s ability to migrate thus reproduction failure.

This article makes me curious about how the White-crowned x Golden-crowned hybrids are born. Do you know why some of them end up mistaking the species to mate while they seem to be very selective about the song dialects?

Hideki

Hi Hideki,

That is an excellent question! There seem to be more questions than answers as to how exposure to varied dialects effects young birds, and whether or not they are be predisposed to discriminate against songs that are not their own. It has been proposed that the mistake of breeding with a different species is evolutionary unfavourable so genetics will favour the ability to “filter out” other species songs they might hear. However, this is not always the case, as we can clearly see hybridization does occur and the fitness of these hybrid individuals is not always less than that of the parent species. It is clearly a complicated subject!

After some further digging I found an interesting article regarding a case of a bird thought to be a Grasshopper x Savannah Sparrow hybrid that was observed to sing Savannah Sparrow songs as well as (strangely) Song Sparrow songs.

Here is a link: https://search.proquest.com/docview/198638643?pq-origsite=summon

There is also another article that specifically tested Golden-crowned Sparrow song learning and responses when exposed to White-crowned Sparrow vocalizations. There was no evidence of hybridization between those two populations however.

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2019/09/06/756445.full.pdf

This is a very interesting topic and perhaps an area for future research as our ability to investigate genetics improves!

Thanks for reading!

Hey Ally! Great blog.

I happen to love these little birds as I have a few that return to my yard and sing quite frequently.

I think its so interesting that they have different “dialects” based on their locations and how they use this to detect other white-crowned sparrows from different territories.

I am just wondering of you came across any information about the predation on these little birds based on their habitats and migration patterns.

You mentioned how some migrate long distances and some do not travel very far at all. Im just curious as to what are the pros and cons of these different migration patterns since some populations do not migrate.

Overall, I really enjoyed your blog.

Cheers,

Mason Friman

Hi Mason,

Thank you!

It is super interesting that different populations of the same species can have such different and distinct characteristics! It was hard to dig up much information on the details of WCSP subspecies migrations. I would suggest that the winter on the west coast is much more mild than central and eastern North America’s tends to be, so the pacific WCSP populations are able to find enough food to sustain themselves through the winter. Since migration is so energetically expensive, if they are able to stay in one location all year, and spend more of their energy on reproduction!

In regards to predation, there was an interesting study I read on how a songbird’s weight affects their likelihood of succumbing to predation. The higher body mass birds take on during migration may affect their maneuverability and ability to get away safely from attacks. This may be another pro of staying put! Here is the link: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1034/j.1600-048X.2003.03049.x?casa_token=z2iqNsNol6gAAAAA%3AsG_povbHyk2NNFPMkhu8ll_0QfMcsnzGeh0aJdL5lPk_UKOnU6VW64yEGSFw4UhM9dOi0YKnkRKqHNY

Cheers, Ally

Thanks for the great read Ally! I see these cuties all the time outside and love to learn more about them!

Its interesting that male White-Crowned Sparrows are mainly only aggressive towards their own subspecies. I wonder if, as hybridization continues, males will become increasingly aggressive to other subspecies.

As a few other comments have mentioned, the use of pesticides and its effects on sparrows (and other birds) is a bit disturbing. Its a little overwhelming how large of an effect 3% exposure to a pesticide can have on the life cycle of sparrows. Since White-Crowned Sparrows on the island are present all year, do they experience similar negative impacts from pesticides? Or is the largest negative impact on migratory sparrows?

Also, weird question that may have not been mentioned in the study, but do you know how researchers estimate exposure levels to pesticides? Do they have to test birds that have died or do they just refer to the amount of pesticide-use a particular area has?

Thank you!

Hi there,

In the study I looked at the doses of imidaclopid were administered based on the birds’ body mass with a high dose considered 3.9 mg/kg of body mass and a low dose 1.2 mg/kg of body mass. These doses were considered non-lethal because they were below the median lethal dose of imidacloprid that was determined from previous studies with captive WCSP.

They determined the level of exposure the birds would encounter in the wild based on typical WCSP food consumption rates and current imidacloprid usage data from the US EPA . Essentially, they determined the high dose was equivalent to <1.5% of their daily diet being seeds treated with imidacloprid.

The question of non-migratory WCSP neonocitinoid exposure is a really interesting (and disturbing) one. This study only considered migrating WCSP in particular, but with such drastic and acute negative effects on their body mass, the results compel us to ask what kind of issues might occur in local populations that may consume contaminated seeds all year. I wasn't able to find any concrete research on neonicitinoid usage or effects on Vancouver Island, but thankfully many pesticides in that category are being becoming increasingly restricted across Canada.

If you are interested in reading more, here is a link to the article that I referenced: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/365/6458/1177

Thanks for your interest!

Ally