by Paula Waatainen EdD, VIU Faculty of Education

“I’d love to ___________, but my students are too ____________________ “

Did you finish my sentence for me? If so, what popped to mind?

I hear some version of this sentence once in awhile, from both practicing teachers and my students preparing for practicum. The “but my students are too…..” blank is filled with all kinds of things.

Too young

Too “low”

Too apathetic

Too marks-oriented

Too disengaged

Once someone followed up their statement with “that strategy may have worked for you at that school, but it wouldn’t work here.

I get the feelings that underlie those statements, having experienced some of them. I once briefly considered not doing an annual model parliament when I worried that some of the students in one of my blocks would be too rowdy. (In the end, that simulation was just what some of those students needed to be authentically engaged in our learning.)

My reaction was coming from a place of middle-of-the-night stress, but I think in other cases it comes from a better place. Perhaps an assumption that there are other things our students need from us before they would be capable of being offered a learning opportunity that is challenging – real-world – authentic – requiring critical thinking. (See article by Roland Case on this)

As we all start a new year, I would like to share two of the many studies that help remind me of the magic that can happen when we begin by assuming that our students are capable of great things, then help them get there.

Capability of children to deliberate on real-world issues

My dissertation research involved having grades 6 and 7 students make submissions to the Reimagine Nanaimo city planning process while their teachers and I worked on trying to design an assessment of the associated competencies. I was curious about the capability of younger students to participate as citizens in a real-world process. I suspected that with the right support and scaffolding, that they were more capable than we might assume, and found this confirmed in my findings (to be discussed in another blog or article).

In reviewing the literature, I was quite taken with a study conducted by Dr. Jennifer Hauver. Her purpose was “to identify the analytic frames children (ages 9 to 11) employed as they worked together to make sense of an ill-structured problem, what those same children did when their frames collided in the context of deliberative dialogue, and what they learned from the process of negotiation” (Hauver, 2017, abstract).

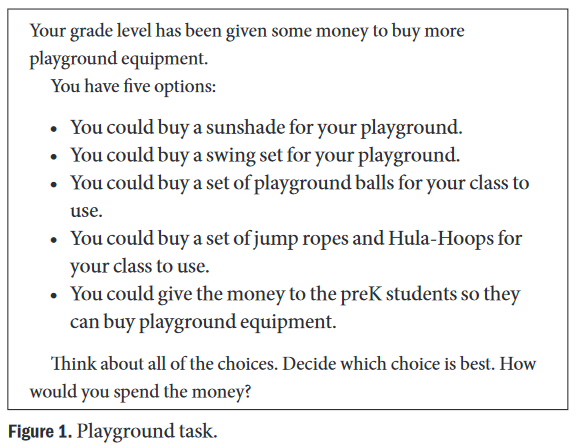

The setting was a 4th grade class at an elementary school somewhere in the American South East. The school’s PTA was considering 5 options to fund finishing the playground at the new school building. These 5 options were shared with the 4th graders, who were put into small groups, with each group engaged in deliberation on which option to recommend to the PTA. Students grappled with a real-world problem that had authentic importance to them, and knew that they would be sharing their results with an authentic audience. Results of the deliberations were shared with the PTA, raising the stakes of the deliberations well beyond a normal classroom conversation.

OK. Have a read over the options that the students were given. What do you think the students would have decided to prioritize for the playground?

If you’d be inclined to fill the blank in my opening sentence with a word like “young” or “self-centered” or “immature”, maybe you’d think “ah – they are just kids. They are going to pick whatever is most fun for their class to use.”

BUZZ – WRONG – TRY AGAIN!

This is not what happened at all.

In analyzing transcripts from the deliberations, Hauver identified common analytic frames visible in the deliberations. They were heavily weighted to considering fairness and the common good, to the point that Hauver named those as “super-ordinate frames, which resonated with peers and facilitated the building of consensus” (abstract). Self-interest as a frame was far, far less common. If a student did propose something that would only benefit their class, other students failed to pick up on those suggestions, and turned the discussion back to making arguments related fairness and the common good.

In responding to this study, Serriere (2017) wrote that researchers have to reject assumptions that young people are incapable of understanding perspectives of others at a young age. She drew on her own research when she wrote:

Like Hauver’s work here on fourth graders who rejected self-centered rationales, we found evidence of kindergarteners eager and willing to investigate multiple perspectives on an ethical dilemma at hand. Thus, it is important that we as scholars and teachers critique

egocentricism as a necessary part of childhood or a linear development. (p.3)

Now doesn’t it just make sense that these students were consulted on an issue like this that would have more authentic importance to them than it would to the adults? But how often do we actually ask those students and act on what they share with us? Here’s a Vancouver example of the magic that can happen when we do:

If we begin by assuming capability in our young students, we give ourselves permission to engage them in challenging, hopeful discussions about the world as they are experiencing it.

By doing so with appropriate scaffolding, we contribute to building the competencies students need, and feel they need, to be our partners in these conversations.

Our planning can then shift to deciding how to frame issues in a way that meets the students where they are, and how best to offer appropriate scaffolding.

“We are Artists”

I spent two weeks in Kelowna this summer, teaching a course for UBCO’s Summer Institute of Education. I found myself thinking often of my friend Sara, and wishing I would have been able to visit her. Sara lived in Kelowna, but died earlier this year from ALS.

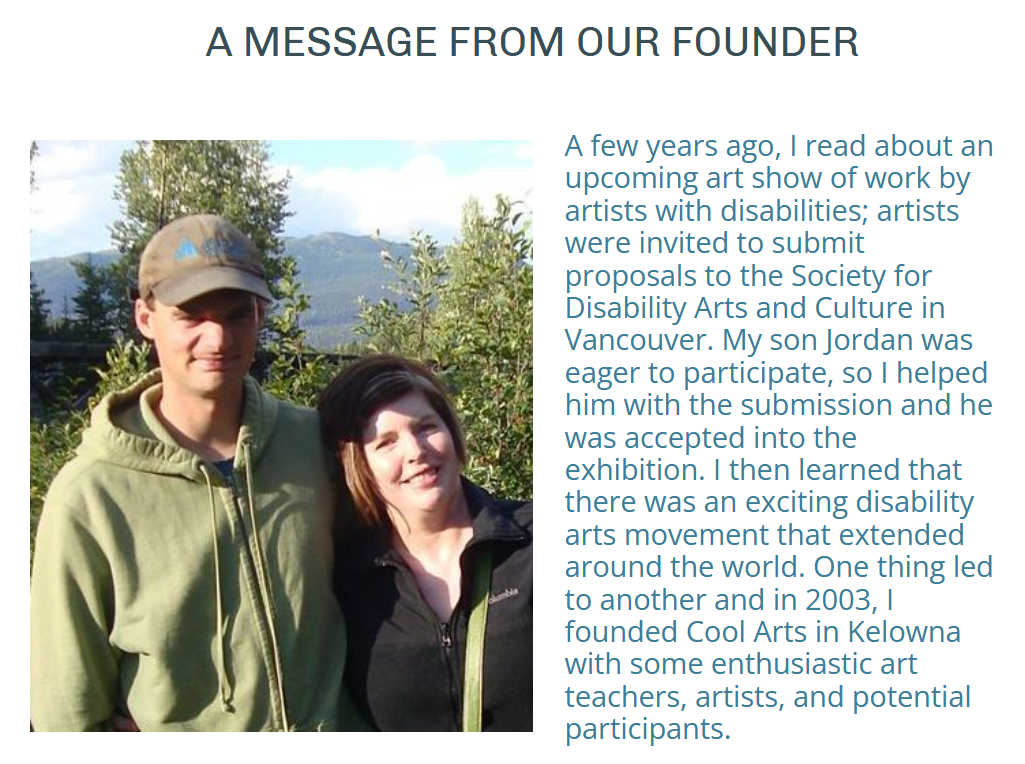

Sara McDonald (formerly Lige) was a talented studio artist and art teacher, a mother and a grandmother, and worked for years at the UBCO campus where I was teaching each morning. Sara was also a formidable advocate and organizer, most recently for ALS funding and awareness, but also for many years in creating an inclusive space in the art world for adults with developmental disabilities. She founded Kelowna’s Cool Arts Society in 2003.

In May 2021, I was following my doctoral supervisor’s advice to read theses and dissertations on many topics to see how the authors had structured their analysis chapters. After my daughter went to bed one night, I downloaded Sara’s thesis Adults with Intellectual Disabilities and the Visual Arts: “It’s NOT Art Therapy! from her MA in Interdisciplinary Studies at UBCO. Several pages in, I messaged Sara to let her know.

I sure didn’t fall asleep! I stayed up too late that night, fully drawn in. I had promised Sara I would skim parts and read only her findings and analysis carefully, but it was too interesting.

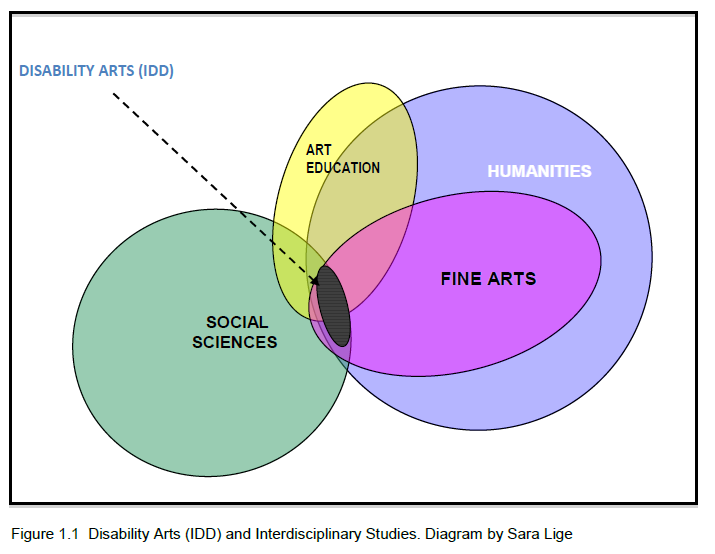

Sara created this diagram to show where her study connected to different fields. She had to cover a lot of ground to show these connections.

As I read, Sara and I wrote back and forth about what I was reading and how I was now reading it with my teacher-educator hat on. I was not her anticipated audience for this work, but it resonated deeply for me in how we think about capability. Sara recommended that I have a close read of the section of her lit review on Tobin Siebers’ research about fabric artist Judith Scott, who lived with Down’s Syndrome.

Sara wrote about Siebers (p. 52):

Siebers identifies as a long-held belief the notion that art is conventionally understood to be produced by ‘genius’, a term that can also be understood as an intelligence capacious enough to carry out works of art, or to use another term, ‘intention’. If art is to be made sense of in this way, then persons with an impaired intelligence cannot create art or are greatly limited in doing so. Siebers takes issue with this premise and asserts that an artist with IDD who produces artwork that is considered to be of a high standard challenges this notion and represents “an absolute rupture between mental disability and the work of art and applies more critical pressure on intention as a standard for identifying artists” (69).

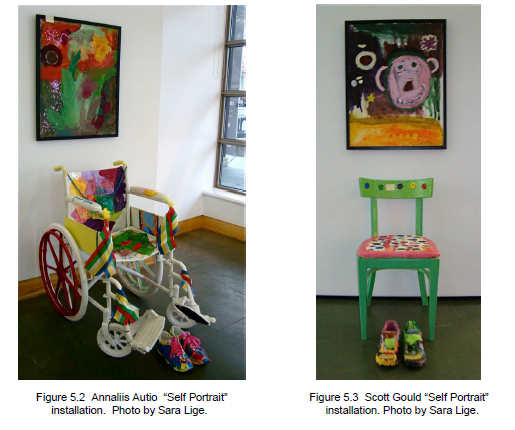

Sara curated the first Cool Arts exhibition at the Kelowna Art Gallery, and I find it exceptionally fitting that it was called “We Are Artists”. The exhibition featured self portraits, each accompanied by chairs and shoes with which Cool Arts artists represented themselves.

In the weeks leading to the opening of the exhibition, Sara began collecting data for her case study of Cool Arts artists. Her research question was “what is the experience of artists living with IDD in the context of their art-making practice, and how does this experience act to help establish that artists with IDD can have an authentic art-making practice?”

Three artists from Cool Arts consented to participate in this study. Sara filmed an art making session with each artist. In follow-up individual interviews, she and each artist watched the video of their art making session. Sara used each video as a prompt to ask the artists questions about their decision-making, to guide them to reflecting on their process.

Sara found that each participant was working in ways that are associated with being an “artist”, such as:

Demonstrating an understanding of materials and technique

Exhibiting individual styles

Engaging in choice-making

Sustaining focus and concentration

Seeing and describing themselves as artist

There are lessons teachers can draw on from this research and from the ongoing work of the Cool Arts Society, where the staff and guest instructors begin with an assumption of capability every day. If I have piqued your interest, I hope that you will download Sara’s thesis here or check out this podcast interview of Sara by her daughter, Rachel. Then start a conversation with your colleagues about how this can inform our impressions of capability. And inclusion.

Have a wonderful start to the school year, and try to begin it also with a sense of your own capability to do the sort of work that you would love to do this year with your students!

Note: I have focused narrowly on the value of starting with an assumption of capability, but I could have easily written this blog post about assessment of capability or competency. The capability of the artists became visible in observing it in action. Sara applied evidence from her observations and conversations and examination of the artists’ work to criteria that she had assembled from real-world application. This blog is too long as it is, so I will save assessment for another day.

So what do you think? Please share your comments about my call for an assumption of capability. What are your experiences?