By Paula Waatainen EdD, VIU Faculty of Education

“Hey Miss Poikonen… what’s nationalism again?”

“Matt”, History 12 student, Sentinel School, June 1995.

My first year of full-time teaching began without warning – as is common – when a call to TOC became a full year leave replacement. I was a 24-year-old with a perm and “bright colours and vests” teacher look, teaching History 12. I needed to know enough about world history in the 20th century that I could adequately prepare students for a provincial exam worth 40% of their mark. I had never taken a course on the Middle East. Or China. Or Stalin. But somehow, I knew a LOT about praetorianism in South Asian politics, nuclear deterrence, and asymmetrical warfare (Finnish Winter War, thanks to family lore) so I allowed myself some tangents.

My students were under pressure to do well on that exam, to secure and hold those seats in university programs. Even the self-proclaimed class clown had applied to, and would attend, a circus university in the US. I gratefully accepted resources and ongoing advice that year from Steve May, the exceptional teacher I had stepped in for. I spent the year working my way through his binders, using his overhead notes, student-led seminars, debates, and research assignments. At the end of each unit, I unlocked the filing cabinet to find the numbered copies of multiple choice / definitions / essay exams, then returned them to the filing cabinet again after the students used them.

Late June: the morning of the provincial exam had arrived.

Students were dropping off their textbooks and picking up peppermints from me to have at their tables in the gym. Maybe they were ready! Maybe it was going to be OK, and they would get into university, and no parents would come shout at me or sue me (that actually happened to a colleague at the school – the judge threw out the case) and I would get another contract for next year! These students were a joy. I wished them well and sensed – correctly – that as my first group, I would remember their faces even after teaching thousands more students.

A few minutes before the exam, “Matt” burst through the door, looking – a little scattered. He was a tall kid with a mass of blonde curls and flushed cheeks, perpetually almost late but not actually late, and always with a smile for everybody. Virtually every mark I gave him all year was 80%. Tests. Homework. Essays. I didn’t really know what I was doing with assessment, but he was so consistent, and appeared to agree with me that 80% was accurate and fair.

“Hey Miss Poikonen… what’s nationalism again?”

Nationalism was a major theme in the curriculum.

Many past provincials had essay questions about it.

We had compared the definition to related terms.

They had applied it to case studies and debated its impact.

They had all made exam prep notes about course themes, including nationalism.

Matt had even attended an optional Saturday exam prep session and had participated in scribbling ideas and timelines on the board for the themes, including this one.

How could he not remember what this concept was? I had failed him! What was the point of any of this work that we had done if Matt, at 80%, needed to ask me what nationalism was?

Maybe I was not cut out for this!

I have no memory of what Matt got on that provincial. He probably did fine, and like the others, went on into more schooling and work and life, and doesn’t remember either. He probably can’t quite come up with my name anymore, just as I can see his face but can’t quite come up with his.

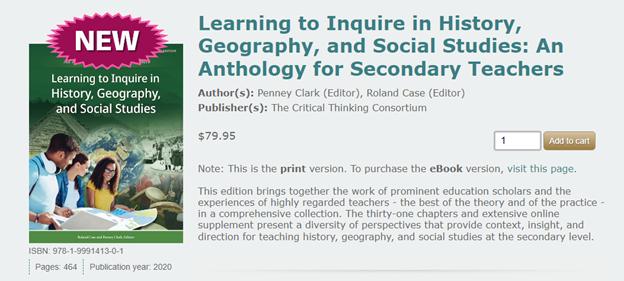

I related this story to Megan, a teacher I met with a couple of weeks ago. She was ending the year concerned her students were not adequately grasping some of the many key concepts in her grade 11 program. I recommended that she look for ideas in the chapter on teaching concepts by John Myers & Roland Case in the anthology that I assign to my secondary Socials Methods students. The chapter provides quite a comprehensive discussion of teaching for conceptual understanding, with many suggested activities.

Roland writes about a conversation with his niece, then in grade 9. Learning she had just scored 96% on a unit quiz on political and economic concepts, Roland asked her a question that would require her to apply capitalism to Canada. He learned that despite her accurate definition, she was unable to apply that definition to real-world examples. She didn’t appear to have much conceptual understanding of capitalism – just that memorized definition.

So. What would that anecdote have me to think about Matt’s conceptual understanding of nationalism? Matt was asking for a definition of this term, so did he go off into the world with less understanding of nationalism than Roland’s niece had of capitalism?

Nope. I don’t think so. 27 years later after Matt’s provincial, I have forgiven myself!

Thanks to the advice and the binders of a master teacher, I did some explicit work that year in exploring the nature of nationalism as a concept. We did a lot more than memorize terms. I suspect that Matt would have been able to draw on some transferable conceptual understanding of nationalism, when, a few months later, he watched the results come in from the Quebec sovereignty referendum, or this year, when he may have seen posts about Ukrainian resistance to Russia’s invasion in his social media feed. Maybe he has never had the occasion to say the word nationalism in all these years, but I hope that somewhere, the shape of this concept informs how he greets relevant new information.

Knowing the sort of explicit work on building conceptual understanding that Megan is doing, I suspect her students were also leaving her class with more conceptual understanding than she could measure with her assessments.

Here is why I think so:

Bransford and Schwartz (1999) reviewed literature on “transfer”, noting how disheartening many studies would appear to educators. The studies they reviewed showed more failures than successes. Students appeared to be struggling to transfer learning from one context to another. But then the authors asked if it could be that the way we tend measure transfer is “too blunt of an instrument” to pick up on it happening so gradually?

A striking feature of the research studies just noted is that they all use a final transfer task that involves what we call “sequestered problem solving” (SPS). Just as juries are often sequestered in order to protect them from possible exposure to contaminating information, subjects in experiments are sequestered during tests of transfer. There are no opportunities for them to demonstrate their abilities to learn to solve new problems by seeking help from other resources such as texts or colleagues or by trying things out, receiving feedback, and getting opportunities to revise. (Bransford & Schwartz, 1999, p. 68)

Bransford and Schwartz proposed an alternative way of looking at transfer, in considering what students learn as “preparation for future learning” (PFL). They cited the work of Broudy (1977) who wrote that in looking for transfer, we tend of focus only on replicative knowledge (“knowing that” – or in our case, knowing the textbook definition of nationalism) and applicative knowledge (“knowing how”). Broudy argued that we also “know with” our previously acquired concepts and experiences; that an educated person “thinks, perceives and judges with everything that he has studied in school, even though he cannot recall these learnings on demand” (p. 77)

Knowing with may be comparable to tacit understanding that people with some degree of expertise have with what they do regularly, even if they can’t pinpoint how this understanding developed over time or operationalize how to explain it. If you are an experienced teacher and have ever supervised a pre-service teacher on practicum, you likely have run into this. Perhaps over the years you have developed a tacit understanding of how to build community in your class but must pause to think about what that entails, so you can explain it to a novice.

The upshot (?)

I hope any of you who read this are starting a well-deserved summer with confidence that the conceptual understandings, dispositions, and competencies your students will be “knowing with” in the future were influenced by the work you did together this year.

Our work in BC on competencies and with proficiency scales has made us all more accustomed to thinking about learning as complex growth on a long continuum, over years. Designing assessments to adequately give us glimpses of that growth is a challenge that teachers across the provinces are rising to. I sense “knowing with” and “preparation for future learning” are ideas, older than our curriculum, that support our intentions.

That’s not to say these ideas make anything easier in practice. While wonderful to imagine contributing to something that may consolidate years later in a student, what are the practical implications for teachers work with students now, in planning for learning, and assessment? What do you think?

One recommendation by Bransford and Schwartz is to design opportunities for authentic inquiry. Something that will have value to students beyond getting an assignment done for class. The focus of most future posts in this blog will be on situating learning and assessment in real-world places, problems, and processes, should you like to come back to have a look again. I will also return to the topic of teaching for conceptual understanding with some links to activities.

Have a great summer!

PS – The glimpses I just provided of the work of Broudy, and of Branford & Schwartz, and the studies they reviewed are inadequate! They say a lot more that is very interesting and useful. If you are interested, I recommend reading further:

Bransford, J. D., & Schwartz, D. L. (1999). Chapter 3: Rethinking transfer: A simple proposal with multiple implications. In A. Iran-Nejad & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Review of research in education, 24 (pp. 61–101). American Educational Research Association. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X024001061

Interesting. Many points and feeling in this blog connected with me (and I am sure many others). Also so realistic how we teachers hold the responsibility of our students’ learning. Don’t get me wrong, I totally disagree with the philosophy that it is a students job entirely to plant and grow the seeds of knowledge I aimlessly toss about but the panicked ” did I do enough ” rings sovtrue. As we take off for our summers a gentle reminder to us all. It is “did we do enough “. Our learning and teaching is a dialogue.