Part 1: The Norther Flicker

The Norther Flicker (Colaptes auratus) is an easily recognizable woodpecker due to the 1920’s inspired black and white polka dot dress and black bib it appears to be wearing. At a maximum length and weight of 31 centimeters and 160 grams respectively (similar to a Steller’s Jay), these birds are the second largest woodpecker in North America behind the Pileated Woodpecker (Cornell Lab of Ornithology 2017). This species of woodpecker exhibit sexual dichromatism, which allows for easy sexing of a bird based on color variations between males and females. Fittingly enough, males sport a proud mustache whereas females go without. Two main groups of Northern Flickers are present in North America: the yellow-shafted (found in the East) and the red-shafted (in the West) (Manthley et al. 2016). Identification between these two groups can be done by comparing the coloration of the nape, mustachial stripe and shafts of the feathers. The Red-Shafted Flicker has a brown nape, red mustachial stripe (males) and the shafts of flight feathers are pinkish red. In contrast, the Yellow-Shafted Flicker has a distinct red nape, black mustachial stripe and bright yellow feather shafts (Cornell Lab of Ornithology 2017).

Distribution, habitat and diet

Unlike most woodpeckers, which are often permanent residents, Northern Flickers may take part in short-distance migrations (Wiebe and Gerstmar 2010). The largest contributing factor dictating the total length of a migration is the original breeding location. Although quite uncommon, some banded individuals have undergone lengthy migrations from northern British-Columbia to the Baja peninsula in Mexico (2882 km) (Gow and Wiebe 2014). The larger proportion of Flicker populations, residing in more southern locations, will typically have much shorter migrations or avoid migration altogether and live a sedentary lifestyle.

Flickers can live in a wide range of environments. Their most common habitats are open forests, forest edges and fields but it is not unusual to see them near lakes, marshes and urban areas (Wiebe and Gow 2012). During the breeding season their diet is almost entirely comprised of ants (<90%). Flickers have also been documented to eat fruits and seeds when ant availability decreases (Wiebe and Gow 2012). Flickers probe the ground with their long bills and barbed tongues to pick away at ants and hidden nutritious larvae. Prey density and catch rate is higher in low grasslands and forest edges when compared to dense forests and very wet habitats. This makes Norther Flickers far more likely to be seen foraging on the ground along the edge of a forest than crawling up the bark of trees in densely vegetated areas like many woodpeckers (Elchuck and Wiebe 2003; Wiebe and Gow 2012).

Nesting, courtship and calls

Even though Northern Flickers prefer to forage for food along forest edges and open habitats, their nesting sites are more predominantly found within dense forests. This ensures a more secretive nesting location and decreases the risk of nest predation (Fisher and Wiebe 2005). Flickers form nest cavities in anything they are able to excavate. These can range from diseased trees, old poles and even the side of homes! Northern Flickers are generally considered primary cavity nesters; they excavate new cavities every year and are its first occupants. In some instances of rare excavation site availability, Flickers have been seen occasionally compete with secondary nesters for occupancy of old abandoned nests. In one instance, a Northern Flicker caused the death of a Whiskered Screech-Owl chick while trying to rearrange the nest for its own use (Estay-Stange et al. 2019).

The Northern Flicker can be territorial during breeding season and engage in elaborate “fencing-duels” to attract a potential mate’s attention. These duels, however, are purely visual and do not involve any sort of physical contact with the competitor.

The song heard during the breeding season is a series of short and loud alternating rising notes that last up to 10 to 15 seconds.

The call heard during the rest of the year is a single loud Klee-yer.

And last but not least, the Northern Flicker can call to others using a short drumming noise made of a series of about 25 strikes. Northern Filckers often have creative ways to amplify their drumming; metal guard rails, metal chimney caps and other man made structures are often used.

Conservation

The Norther Flickers are listed as a species at low risk of extinction as they are quite common and widespread. Their population has been monitored for a period of 44 years and a yearly decline of 1.5% of the population has been estimated (Cornell Lab of Ornithology 2017).

Part 2: Increased parental care in Northern Flickers: Great dads but at a cost.

The previous section outlined the general life history of Northern Flickers and exposed some unusual aspects of their behaviour when compared to other North American woodpeckers: partial migration, near exclusive ground foraging and occasional secondary cavity nesting. Their uniqueness does not stop there! Research on Norther Flickers has revealed that the males are responsible for the majority of parental care due to partially reverse sex roles (Gow and Wiebe 2014: Wiebe 2008).

For bird species with altricial young (chicks unable to move or feed on their own after hatching), parental care is most commonly associated with the females. In Northern Flickers, multiple factors are responsible for shifting the balance of traditional sex roles. Male Flickers are primarily responsible for finding suitable nesting sites and excavating them. After laying the eggs, the males and females have two hour rotation intervals during daytime incubation. At night, males are mainly responsible for the incubation of the eggs. This cycle results in females only being responsible for 8 hours of incubation per 24 hour period (33%) (Wiebe 2008). Although most pairs are monogamous, female Northern Flickers can sometimes be polyandrous. This means that one female may have more than one partner during one breeding season. The females can afford the increased energetic cost of multiple partners since Norther Flicker eggs are among the smallest when compared to female body mass and also have some of the lowest nutritional support for the developing embryo (Gow et al. 2013). Polyandry can result in decreased participation by the females and complete lack of maternal care in extreme cases. Male Norther Flickers have adapted to the higher incubation times by having a highly developed and vascular brood patch, making them equally efficient for incubating as females (Wiebe 2008). Despite low attendance of some females, male flickers choose to sacrifice future reproductive success and body mass rather than abandoning the clutch in order to assure paternity (Wiebe 2008: Gow et al 2013). Small males required less support from females than males with greater body mass due to a lower energetic and metabolic demand.

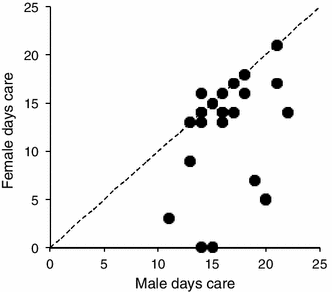

Feeding frequency of recently hatched chicks is equally shared between males and females, but tends to differentiate as young birds age. This species has an inverse relation with female feed rates and nestling period. Females were found to greatly reduce their feeding contribution as brooding demands increased during the late nestling periods (Gow et al. 2013). Older females were significantly more likely to abandon nests during these late periods (Wiebe 2008). A recent study discovered that 36% of females deserted the nests prior to fledgling independence, whereas no males were observed to do so (Gow and Wiebe 2014).

All of the extra energetic demand required by males during the breeding season comes at an extra cost. Bird banding records and geolocator data indicates that male flickers migrate farther South than females during winter (Gow and Wiebe 2014). This contradicts previous migratory trends observed in other species, where females are typically observed to migrate greater distances. Three main hypotheses are widely accepted to describe this behaviour: males winter in more northern locations in order to arrive on breeding sites earlier to increase reproductive success, larger males are able to withstand harsher wintering conditions and may also force smaller and less dominant individuals to migrate farther (Gow and Wiebe 2014). None of these hypotheses can be used to explain why male Northern Flickers migrate over greater distances than females. The males have a near assured chance of reproductive success (due to female behaviour) and are of identical size to the females (less than 3% variation). The fasting endurance hypothesis appears to be the most likely candidate. This suggests that the males, facing greater risk of starvation due to depleted energy stores, must travel greater distances to find better wintering habitats in order to recuperate from the exhaustive mating season (Gow and Wiebe 2014).

Northern Flickers are striking woodpeckers with a wealth of interesting behaviours that set them apart from the rest of their family. It is no wonder why so much time has been devoted to the research of these birds. Amazing and unknown finds always await further discovery, such as the fact that these devoted mustached males are able to retain a caring heart towards their offsprings even if it means travelling farther for a well-earned vacation.

References

Elchuck, C.L. and Wiebe, K.L. 2003. Home-range size of northern flickers (Colaptes auratus) in relation to habitat and parental attributes. CAN J ZOOL [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 81(6): 954-961. DOI: 10.1139/z03-077

Estay-Stange, A.E., Rodriguez-Estrella, R. and Bautista, A. 2019. Injuries to a whiskered screech-owl (Megascops trichopsis) chick inflicted by a northern flicker (Colaptes auratus) in a nest cavity. WILSON J ORNITHOL [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 131(1): 195-198. DOI: 10.1676/17-24

Fisher, R.J. and Wiebe, K.L. 2005. Nest site attributes and temporal patterns of northern flicker nest loss: effects of predation and competition. BEHAV ECOL [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 147(4); 744-753. DOI: 10.1007/s00442-005-0310-2

Gow, E.A. and Wiebe, K.L. 2014. Determinants of parental care and offspring survival during the post-fledging period: males care more in a species with partially reversed sex roles. OECOLOGIA [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 175(1): 95-104. DOI: 10.1007/s00442-014-2890-1

Gow, E.A. and Wiebe, K.L. 2014. Males migrate farther than females in a differential migrant: an examination of the fasting endurance hypothesis. ROY SOC OPEN SCI [cited October 1]; 1(4): 140346-140354. DOI: 10.1098/rsos.140346

Gow, E.A., Musgrove, A.B. and Wiebe, K.L. 2013. Brood age and size influence sex-specific parental provisioning patterns in a sex-role reversed species. J ORNITHOL [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 154(2): 525-535. DOI: 10.1007/s10336-012-0923-2

Manthley, J.D., Geiger, M. and Moyle, R.G. 2016. Relationships of morphological groups in the northern flicker superspecies complex (Colaptes auratus & C. chrysoides). SYST BIODIVERS [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 15(3): 183-191. DOI: 10.1080/14772000.2016.1238020

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2017. All About Birds: Northern Flicker. [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1] from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Flicker/id

Wiebe, K.L. and Gerstnar H. 2010. Influence of spring temperatures and individual traits on reproductive timing and success in a migratory woodpecker. AUK [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 127(4): 917-925. DOI: 10.1525/auk.2010.10025

Wiebe, K.L. and Gow, E.A. 2013. Choice of foraging habitat by northern flickers reflects changes in availability of their ant prey linked to ambient temperature. ECOSCIENCE [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 20(2): 122-130. DOI: 10.2980/20-2-3584

Wiebe, K.L. 2008. Division of labour during incubation in a woodpecker Colaptes auratus with reversed sex roles and facultative polyandry. IBIS [Internet]. [cited 2019 October 1]; 150(1): 115-124. DOI: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2007.00754.x

Hi Jonathan,

Great blog! I don’t think I will ever forget your comparison of the Northern Flicker’s plumage to a 1920’s polka-dot dress, haha! A pretty accurate description. They really are a studly woodpecker! I also really like the video you added in of their courtship “fencing-dual”, I have seen it before but I didn’t realize it was their way to attract the attention of possible mates. It looks like they probably have some 1920’s music playing in their head to match those moves!

I knew that flickers and other woodpeckers shared the incubation work (that’s why brood patches won’t help you determine their sex!), but I had no idea that the males did the majority of the share. Very interesting. Did you come across anything in your research about this bahaviour being the consistent in other woodpecker species – where males do the majority of the work for parental care?

Again, awesome job!

Samuelle

Hi Samuelle,

That is a great question! I read through a few articles, as I was unsure as well, and found an interesting trend. The research seems to reaffirm that woodpeckers tend to have a higher degree a paternal care that most other species of birds. A research conducted in Sweden, on Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers, found a degree of paternal care similar to that of NOFL. Males were responsible for the majority of nest excavation, incubation and also fed the chicks for a longer duration since females also had a tendency to desert the nests. Polyandry was also common amongst the Spotted Woodpeckers. Other articles point out that the degree of paternal care can fluctuate depending on the species of woodpeckers (ie. some species’ males may do more nest maintenance and cleaning while other species may feed larger prey or do incubation).

So, all-in-all, paternal contributions seem to be at least equal to maternal contributions in some species and up to mostly paternal in others.

I hope this helped in clarifying your a question a little?

Thanks for reading my post!

Jonathan

P.S. here are articles about parental care in woodpeckers

1) Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1034/j.1600-048X.2000.310003.x

2) Hairy and White-Headed Woodpeckers: https://bioone.org/journals/the-wilson-journal-of-ornithology/volume-125/issue-3/12-188.1/Nestling-provisioning-by-Hairy-and-White-headed-woodpeckers-in-managed/10.1676/12-188.1.short

Hey Johnathon,

Well done, I really enjoyed reading more about Northern Flickers! I’m curious about why they drum on trees/ human made structures? Is it for mating purposes, territory signalling, or just to call to each other? I used to have one that drummed on my stove pipe and sent a loud rattling all the way into my house a few times a day!

Ally

Hello Ally,

Wood peckers have been responsible for many angry homeowners. Check out this video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GrEbH3MwHSA). This would be terrible to hear at 6:30 in the morning!

Your guess was spot-on! A recent article mentions that drumming, used by woodpeckers, is used to attract mates and signal territoriality to other near-by woodpeckers. The study I read mentioned that the speed and loudness of the drum may well be used to broadcast physical fitness to mates for two reasons. The first reason (rate of drumming) is that a rapid and constant drum requires very well developed musculature of the neck and head which indicates good health and genetics. The second reason (loudness) indicates similar features as well as increased cognitive ability to find better resonating surfaces (chimneys, metal rails, etc).

Thank you for your comment,

Jonathan A.

P.S.

Here is the article: http://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC5802847&blobtype=pdf

Hi Jonathan!

Amazing blog! I found it very interesting that Northern Flickers’ diet consist mostly of ants! I would have thought, based on their family, they would eat insects found in trees. I was curious as to why this is, seeing as they are fully capable of drumming through tree bark and into trees to excavate their own nests.

I was also curious as to which sex creates the nest. If males are the nest-makers as well at the primary caretakers of the clutch at night, where do the females go, and do they excavate their own nests?

Your blog was fun to read and flowed very well!

Thanks,

Melissa

Hi Jonathan,

Really great job on your blog! I loved the video of the Northern Flicker’s “fencing duels”! It seems like a really interesting ritual and would be pretty cool to be able to see!

I had a question about their conservation. You said that the population is seeing a decline of 1.5% per year and I was just wondering whether you found what was causing this small but still present yearly decline?

Thanks for teaching me about the Northern Flicker!

Danielle

Hi Danielle,

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment on my blog!

As you mentioned in your question, NOFI populations are declining at quite a slow rate. There was not a whole lot in the way of research specific to Northern Flicker conservation, but some key points can still be taken from conservation studies done on other woodpeckers.

It seems that the greatest factor that would be affecting their decline is the loss of suitable nesting habitat due to deforestation. Flicker’s rely on older trees with softer insides to excavate or sometimes use old cavities. This means that the loss of suitable trees combined with increased competition for holes with non-excavating species could increase the stress for nest acquisition. Additionally, Flickers tend to prefer nesting near forest edges (instead of densely forested areas) which may be favoured areas by other competing species.

Thanks again,

Jonathan A.