Part 1: An Introduction

The black-capped chickadee (ORDER Passeriformes, FAMILY Paridae, SCIENTIFIC NAME Poecile atricapillus), is an adorable bird measuring between 12 to 15 centimetres in length and weigh an average of about 11 grams! They have grey backs, dark grey wings and tails, with the white edging on the feathers. They are distinguished by their black cap that covers their eyes, white cheeks, a triangular black bib on their throat, and buffy (dull-yellow or yellowish-brown colour) sides that fade to a white chest.

While chickadees make a variety of calls, songs, and sounds, the most recognisable is the chickadee-dee-dee. Another common call, usually used by males during nesting season (late winter), is the fee-bee or fee-bee-bee, where the first note is usually higher and longer than the second or third (Hinterland Who’s Who, 2003).

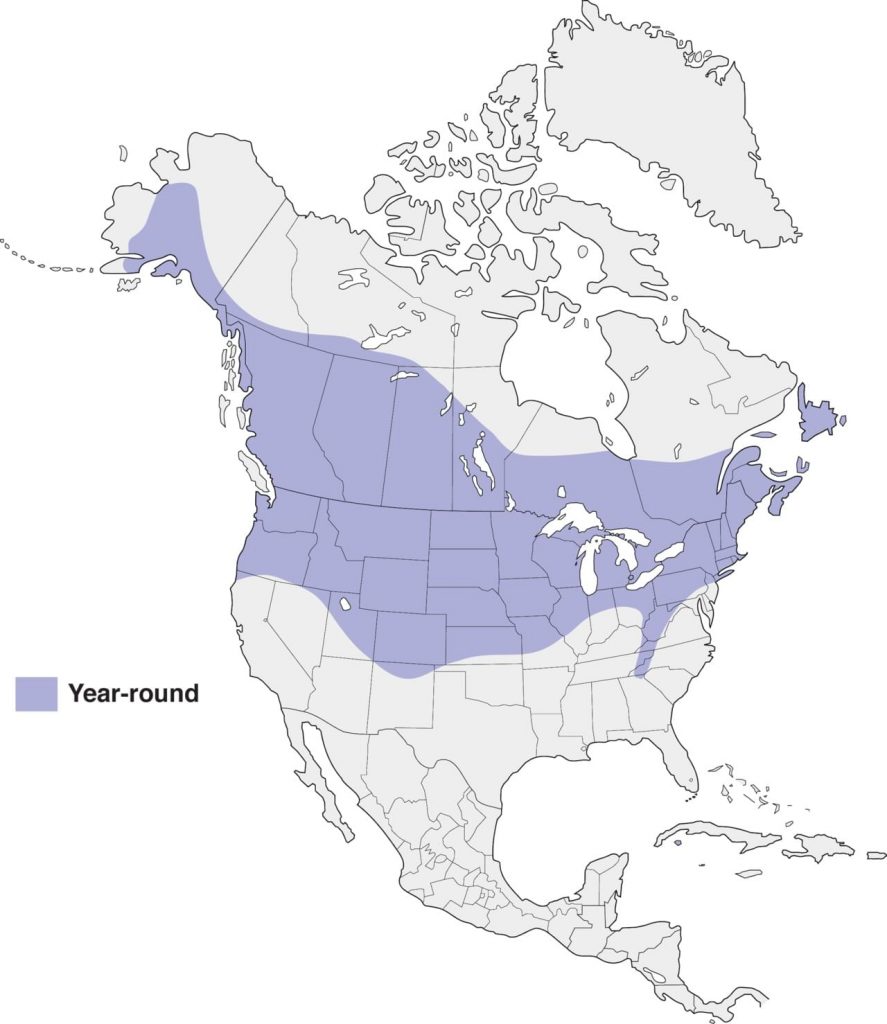

Black-capped chickadees are found throughout Canada and the United States. They habit central and southern parts of Alaska, southern parts of the Yukon and Northwest Territories in the north and extend as far south as Oregon, Utah, Kansas, Ohio, North Carolina, and the eastern-most states. They also range from Newfoundland to British Columbia, except for the coastal islands. The reason black-capped chickadees do not occur on the coastal islands, such as Vancouver Island, is thought to be due to resource competition with Chestnut-backed chickadees (Wright, 2015). However, more research has to be done on this topic.

Black-capped chickadees are a non-migratory species. However, when reproduction is high, juveniles may travel long distances. Such events are called “irruptions” and can also occur due to habitat destruction (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2017). Additionally, large numbers of birds are seen flying southward in the fall and are called “invasions” (Audubon, 2019).

Black-capped chickadees live in a variety of wooded areas and in deciduous and mixed forests. This can include woodlots, orchards, forests, residential neighbourhoods and parks, fields, and marshes (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2017). They nest in holes, sometimes old woodpecker holes, in soft or rotting wood, or in nesting boxes (Audubon, 2019).

In the fall and winter, chickadees live in flocks of up to 12 birds. Each flock establishes a social hierarchy, or “pecking order”. The determined dominant individuals get first access to all resources. Within the flock, the birds pair up according to rank, with the more dominant and/or aggressive females with the most dominant and/or aggressive males. Once the pecking order is determined, the flock will defend its territory fiercely. (Canadian Wildlife Federation, 2019)

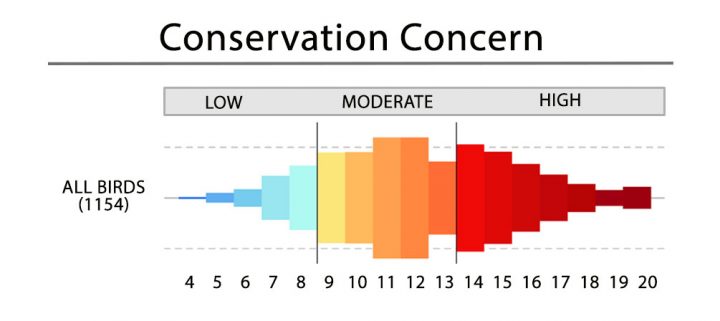

This species is very common, and the North American Breeding Bird Survey shows that populations have slightly increased between 1966 and 2015. Estimates show the population total to be approximately 41 million individuals. It rates a 7 out of 20 on the Continental Concern Score (State of the Birds, 2016) and did not make it to the 2016 State of North American’s Birds’ Watch list. Contrasting to many other bird species, removal of trees for human development projects can increase the amount of forest edge, which improves chickadees habitat. However, they can suffer if too many dead trees are removed for their habitat zones due to it being their choice of nesting site. (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2017)

Black-capped chickadees are very easy to attract to backyards. Suet, sunflower seeds, and peanuts are the best ways to bring these little guys closer. When there is plenty of food to go around, they will hide pieces over its territory for when food is scarcer, or for a midnight snack! They have an amazing memory and can remember where they hid their food for up to 28 days (Hinterland Who’s Who, 2003)…so much for bird brained! In some cases, black-capped chickadees will actually come and eat from a persons hand.

Each fall, Black-capped Chickadees allow brain neurons that store old information to die to replace them with new ones so they can adapt to changes in their flocks and environment (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2017)

Part 2: Fatal Interactions – Dominance and Aggressive Interactions within the Species

During an observation in 2010, researchers David Hof and Nicole Hazlett observed an interaction between two male black-capped chickadees. The pair noticed “gargle” calls near a feeding station. When they approached the source of the calls, they heard rustling and saw a colour-banded male fly from the ground to a perch. After a few moments, they watched the male fly back to the same spot on the ground and start pecking at something. After observing the male for a few minutes, they approached a bit closer and saw that he was pecking another chickadee. After watching the first chickadee peck the other for approximately five minutes, the pair approached the birds until the first male flew away. They then determined the second, identified as another male, was dead. (Hof and Hazlett, 2012)

Based on these observations, it was found that interactions between black-capped chickadees can turn fatal. The pair referenced another documented case of intense fighting during intraspecific (produced, occurring, or existing within a species or between individuals of a single species – Oxford dictionary) interactions from Otter and Ratcliffe in 1996, however the interaction was not fatal due to the researchers intervening. (Hof and Hazlett, 2012)

Aggressive, and sometimes fatal, interactions such as the one observed by Hof and Hazlett are predicted to be between two equally matched individuals (Enquist, Leimar, 1990). In this case, these two males had been observed for three years and both were documented as dominant and aggressive. (Hof and Hazlett, 2012)

Hof and Hazlett noted the sound of “gargle” calls during the attack. Gargle, or fighting calls (Dixon, Stefanski, 1970), are a sign between chickadees during close-range interactions to help establish ones dominance over the other . The point of the dominant males gargle call is to produce a submissive response from other males in the area. Based on the pairs observation of the fatal interaction, gargle calls provide information such as extreme aggressive states or predicting attacks between individuals. (Hof and Hazlett, 2012)

The use of gargle calls in predicting attacks was the subject of another article focused on black-capped chickadees and aggressive interactions. In this case, the researchers involved used five taxidermic mounts of male black-capped chickadees from individuals in Ontario, where the study occurred, that had been found dead from window-kills or had died naturally. The mounts were attached to a speaker apparatus that played recordings of chickadees collected from the same area in 1999. The vocalisation recordings were played for up to 20 minutes or until an attack on the mount occurred. The researchers considered an attack to be any contact made with the mount, usually by individuals landing on the mount’s head or shoulders and pecking at the head and/or eyes. The mount and recordings attracted 38 males, 21 of which attacked the mount within 20 minutes of the start of the recordings being played. All of the attackers produced gargle calls in the minute before attacking; the other 17 observed males that did not attack never made any calls. (Baker, Wilson, Mennill, 2012)

References

Baker, T. M., D. R. Wilson, and D. J. Mennill. In press . 2012. Vocal signals predict attack during aggressive interactions in Black‐capped Chickadees. Animal Behaviour.

Canadian Wildlife Federation. 2019. Black-Capped Chickadee. [Internet] http://cwf-fcf.org/en/resources/encyclopedias/fauna/birds/black-capped-chickadee.html

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2017. All About Birds: Black-Capped Chickadee. [Internet] https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Black-capped_Chickadee/overview

Dixon, K. L., and R. A. Stefanski. 1970. An appraisal of the song of the Black‐capped Chickadee. Wilson Bulletin 82: 53– 62.

Enquist, M., and O. Leimar. 1990. The evolution of fatal fighting. Animal Behaviour 39: 1– 9.

Hinterland Who’s Who. 2003. Black-capped Chickadee. [Internet] http://www.hww.ca/en/wildlife/birds/chickadee.html

Hof, D., Hazlett, N. 2012. Mortal combat: an apparent intraspecific killing by a male Black-capped Chickadee. Journal of Field Ornithology 83: 290-294

National Audubon Society. 2019. Guide to North American Birds: Black-capped Chickadee. [Internet] https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/black-capped-chickadee

Otter, K., and L. Ratcliffe. 1996. Female initiated divorce in a monogamous songbird: abandoning mates for males of higher quality. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 263: 351– 355.

State of the Birds. 2016. Methods – Conservation Status Assessment. [Internet] http://www.stateofthebirds.org/2016/overview/methods/

Wright, K.G. 2015. Black-capped Chickadee in Davidson, P.J.A., R.J. Cannings, A.R. Couturier, D. Lepage, and C.M. Di Corrado (eds.). The Atlas of the Breeding Birds of British Columbia, 2008-2012. Bird Studies Canada. Delta, B.C. http://www.birdatlas.bc.ca/accounts/speciesaccount.jsp?sp=BCCH&lang=en

Hi Melissa,

Nice blog! Black-capped Chickadees are pretty cute! It’s interesting that they replace older neurons in order to adapt to changing environments. It seems almost counterintuitive, but a BCCH has to do what a BCCH has to do!

For such cute tiny little birds, they seem to be quite mean to one another. It’s fascinating that their hierarchy relies on sometimes fatal interactions. Did you come across anything in your studies that suggests other chickadee species do the same thing? From my experience, BCCH seem the most aggressive, but I have no idea if other species have the same infraspecific interactions.

Thanks, and again great job!

Samuelle

Hi Sam,

I did come across a study called “Interspecific dominance relationships and hybridisation between black-capped chickadees and mountain chickadees” (https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/23/3/566/223347/) where the researchers looked at the interactions between the two species. They found that BCCH were the dominant species where the habitats overlap in the Rocky Mountains (BCCH prefer lower elevations, where the mountain chickadees prefer higher elevations). I found it interesting that, in this study, they found that even the female BCCH was dominant over the males of the mountain chickadees and the juvenile BCCH were dominant over adult mountain chickadees where the ages of the individuals were known.

It seems to me that the study suggests that mountain chickadees have a similar hierarchy system…no totally sure if this is the case, though! And I couldn’t find much else in the articles I used on other species of chickadees, but similar studies have been done on vocalisations and dominance in other songbirds, such as swamp sparrows.

But I suppose their cuteness makes up for their aggressiveness in most cases!

Thanks for the question, Sam!

Awesome blog, Melissa!

As you already know, I have a new love for these little birds after feeding them directly from my hands.

In your blog you mentioned that they remember where they hid their food for up to 28 days. Im just curious if that is normal for them or if they have been recorded to remember after more than 28 days.

I guess my only real question here is how good of a memory do they have? If they can remember food stores from 28 days ago that points to them having wonderful memories. Probably even better than my own, i can hardly remember where I put my keys a few hours after putting them down.

If these little birds have such great memories do you think the ones at Rifle still remember us?

You did a really good job with your blog.

Cheers,

Mason Friman

Hi Mason! Thanks for reading my blog!

To answer your question, most studies conducted on BCCH food caching memory state that the best results for food recovery are between 3 to 24 hours at best. But I found a paper of memory in food caching animals that also stated “most studies with parids have suggested much shorter memory durations. For example, Hitchcock and Sherry (1990) found that black-capped chickadees did not find their caches at better than chance levels after postcaching intervals over 28 days.” This mainly has to do with the amount of time food is available to them. BCCH cache and recover during winter when food is more scarce, which means it only *really* needs to be stored for shorter periods of time.

I’d like to think the one’s at Riefel will remember us, at least for a while! I guess our trip also proved the fun fact about them eating right out of your hand!

Thanks again,

Melissa

Kamil, Alan C. and Gould, Kristy L., “Memory in Food Caching Animals” (2008). Papers in Behavior and

Biological Sciences. 61.

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibehavior/61

Hey Melissa,

Great job on your blog! These little guys sure are cute!

I really liked how you discussed that these birds develop pecking orders. I didn’t know this and found it super interesting how they do this in the fall and winter. My question is just whether you know why they don’t stay in these groups with pecking orders all year round? I’m assuming they don’t need to do this at other times in the year because resources are much higher?

Also, it is really interesting that they have such an amazing memory! Crazy that they kill off brain neurons every fall to basically “reboot” their system!

Great job on the blog!

Danielle

Hi Danielle!

Thanks for reading my blog! So most of what I could find on intraspecific dominance was observances from winter flocks (not helpful!), but I found some anecdotes from older studies that may help. I’d like to start by mentioning that flocks are made up of loosely aggregated individuals. They have some small sub-units that tend to flock together, which helps increase chances of finding food and avoiding predators.

First, one study from 1976 noted that discrete units (6 individuals on average) began forming around August (Smith). Second, a study from 1942 noted that between January to April, there is definite dominance and that dominance order doesn’t change much during the Spring. However, during the non-breeding season, birds don’t attempt to drive others away. This study also noted that dominance in not linear and is always subject to change (Odum). I suppose some submissive individuals get brave and happen to drive off a more dominant bird from time to time!

Most of the dominance displays and aggression is, like you suggested, due to lack of resources. This includes food, nest boxes, and females. However, BCCH have also been know to show dominance displays (fighting) as more of a social trait instead of being associated with feeding.

These feisty little guys can be bullies, but they make up for their bad attitude in cuteness (in my opinion)!

Thanks for the great question!

Melissa

Smith, S. M.1976. Ecological Aspects of Dominance Hierarchies in Black-Capped Chickadees, The Auk, Vol. 93, No. 1, pp. 95-107. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4084835

Odum, E. P. 1942. Annual Cycle of the Black-Capped Chickadee: 3, The Auk, Vol. 59, No. 4, pp. 499-531. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4079461