Introduction to the Warbling Vireo

Description and Identification

The Warbling Vireo (Vireo gilvus) is a member of the Order Passeriformes and Family Vireonidae, of which there are about 15 species in North America (Audubon). Like the plumage in most vireos, the Warbling Vireo is mostly drab with subtle or indistinct markings. Specifically, the Warbling Vireo is described as having a greyish-olive head and back, washed yellow along the flanks, with plain, pale lores (the area just between the eye and the bill of birds) creating a “blank-face” look (Sibley, 2000). What this description lacks is that it does not describe how beautiful and effortlessly elegant this species is. Their plumage, colours fading into one another so smoothly, looks as though an artist just finished a watercolour masterpiece.

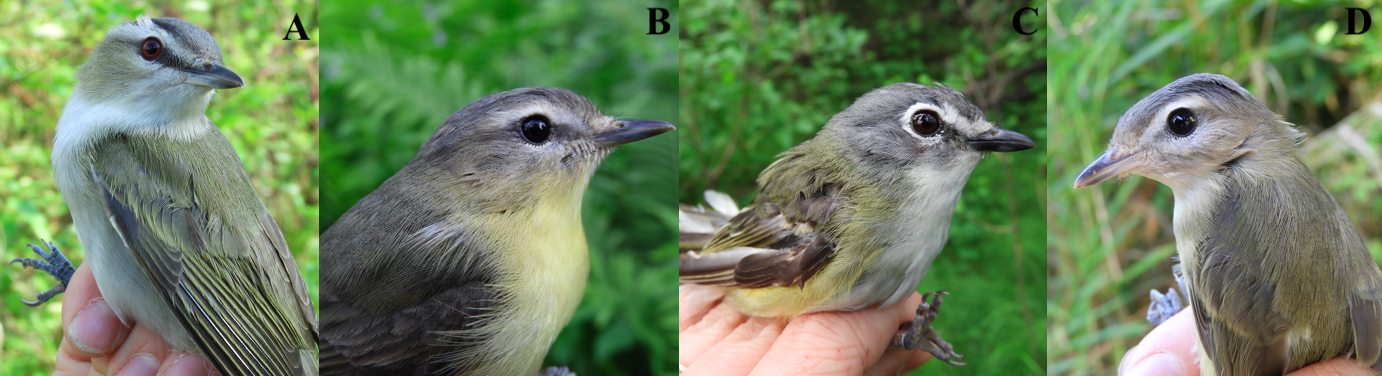

To make things even more interesting, there are also regional differences in Western and Eastern subspecies of Warbling Vireos that can make challenging identifications even more difficult. Overall, the Warbling Vireo is a medium-small, somewhat chunky passerine (perching birds) with a thick, straight, and slightly hooked bill (Cornell University: All About Birds). As seen in Figure 2, different species of vireos can have very similar appearances with subtle identifying field marks.

While the outward physical appearance of Warbling Vireos may be considered drab, their songs are anything but. One of the most melodious and ever-present songs we can hear all summer in North America belongs to this wonderful bird. Aptly named, the Warbling Vireo’s song is a rapid run-on warble, and was poetically described by ornithologist William Dawson as so: “Fresh as apples and as sweet as apple blossoms comes that dear, homely song from the willows.” (Cornell University: All About Birds). Again, just like their physical appearance, Western and Eastern subspecies of Warbling Vireos show a difference in songs and calls significant enough for hobby bird watchers to distinguish. On top of all this, because these guys love to give us a challenge, different populations within each subspecies may also present slight and subtle difference in song and call (Sibley, 2000). This observation may be due, in part, to the idea that song is learnt rather than ingrained in Warbling Vireos.

Studies have shown that among passerines, song development can be influenced by other individuals of the same species, and sometimes even by individuals of a closely related species (James, 1976). Furthermore, species that predominantly use the song-learning strategy to develop their final adult song show a greater degree of song variation compared to species that do not learn their song from others (James, 1976). For species such as the Warbling Vireo, this phenomenon would explain why we observe such variation in call and song across their range. How neat is that? (Pretty neat!)

Habitat and Distribution

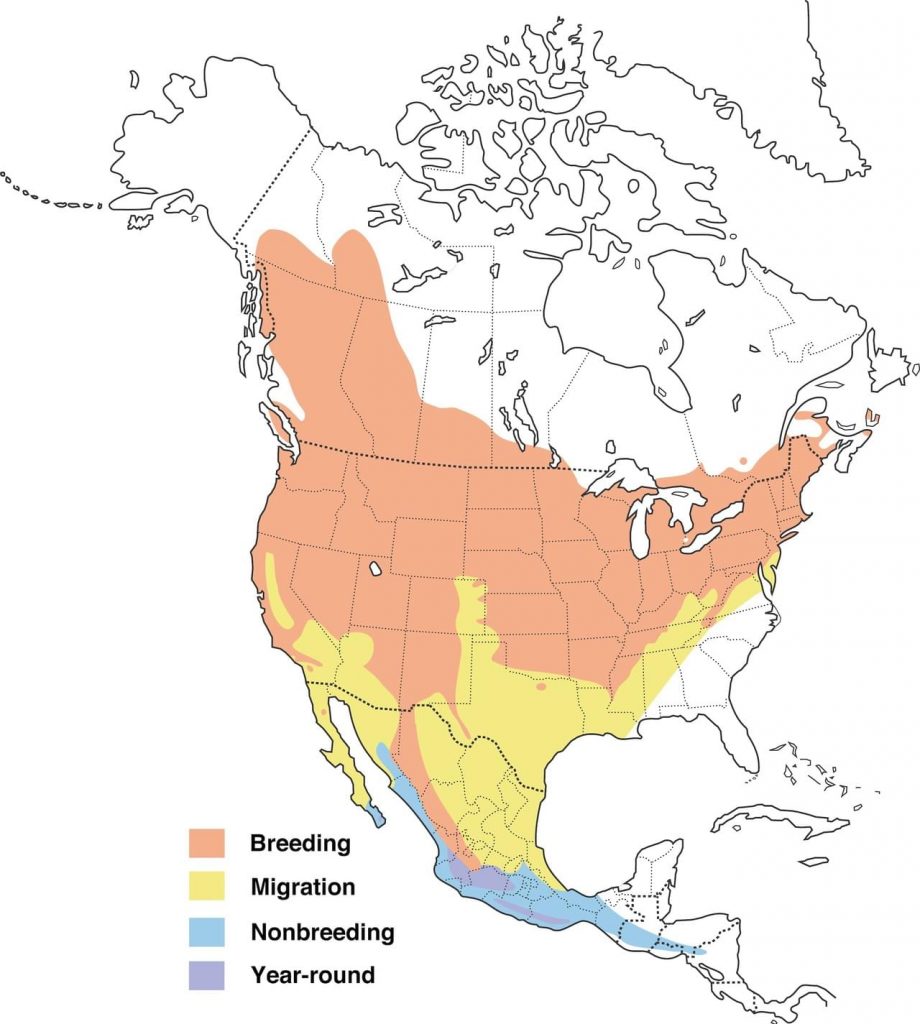

The Warbling Vireo is a common insectivorous passerine species found throughout North America during the breeding season (May-August). Figure 4 shows the expected range for Warbling Vireos during breeding season, migration, non-breeding (wintering) grounds, and where the species can be expected to remain year-round.

Within its broad geographic range, the Warbling Vireo can be found eating insects and sometimes berries in deciduous woodlands (Cornell University: All About Birds). Warbling Vireos are not too picky when it comes to where they choose to spend their time; mature forests or young deciduous stands that emerged after clear-cutting will both do the trick. However, they do tend to avoid dense un-broken forests (Audubon). They particularly like being near water, so are often spotted in treetops along riparian zones (along rivers and streams), marshes, ponds, and lakes (Cornell University: All About Birds). Because of the wide range of habitat these birds can occupy, they are a commonly observed species in neighbourhoods, which is why many people are familiar with their song (Cornell University: All About Birds).

Conservation

Warbling Vireo populations are numerous and are generally doing well throughout their range. Warbling Vireos may attribute their steady numbers to their adaptability to human landscapes and their capacity to breed in fragmented forests (Tewksbury et al, 1998). However, factors such as climate change, window collisions, pesticides, and domestic cats continue to pose a threat to many bird species, including Warbling Vireos.

General Behaviour

Warbling Vireos, like most other vireos, are generally found flitting around foraging among the leaves and hawking and flycatching insects in the treetops (Cornell University: All About Birds). Hawking is a feeding strategy for birds where they capture insect prey in the air while in flight. It is very similar to the flycatching feeding strategy, in which case there is emphasis on the bird being perched immediately before and after catching its prey. If you are trying to spot a Warbling Vireo, they tend to hop around branch to branch in the vegetation, but they will stay put for a few seconds before they move again. This can be said about most vireos. Warblers (another family of passerines), in comparison, do not generally stay still for as long as vireos do.

Nesting Behaviour

Warbling Vireos nest in the outer branches of deciduous trees, between 1-47 meters off the ground (Cornell University: All About Birds). Their small 7.5 centimeters wide and 5-7.5 centimeters deep nests that hang suspended from a forked branch are built almost entirely by the female and consist of soft material like animal hair, cobwebs, cotton, lichen, plant matter, and willow down (Cornell University: All About Birds). During nest construction and incubation, the male defends the female from other males seeking extra-pair copulation (defined as the promiscuous copulation behaviour of monogamous species). The average nest has about four eggs, and Warbling Vireos can have up to two broods per breeding season (California Partners in Flight). Both the male and female Warbling Vireo help take care of the young nestlings, but the female does the majority of the work (Cornell University: All About Birds).

Research on Nesting Ecology

Now let us take a look into some research topics on the interesting nesting ecology of Warbling Vireos. We will first explore cases of interspecific (between two different species) breeding of vireos and follow up with brood parasitism. Let’s dive in!

Hybridization

Hybridization (where two different species copulate to produce a hybrid individual) has been well documented in birds and it is typically due to extra-pair fertilization. In rare cases, hybridization is a result of socially bonded individuals, birds who have decided to nest together for the breeding season (McKee et al, 2016). McKee et al. (2016) investigate interspecific pair-bonding and hybridization in Warbling and Red-eyed Vireos. The limited observed cases of these successfully breeding pairs is interesting because while the two species share a similar geographic distribution, the observed cases were in the Western regions where Warbling Vireos are plentifully common and Red-eyed Vireos are in low numbers (McKee et al, 2016). This paper highlights some important questions regarding vireo nesting ecology. Why would a female Warbling Vireo choose a Red-eyed Vireo mate when male-male song competition is an important deciding factor in mate selection? If you remember way back to the beginning of this blog, I mentioned how the learnt song strategy in vireos can lead to variation in their adult song. This phenomenon, along with the fact that Warbling and Red-eyed Vireos share similar appearances and natural histories, may play a crucial role in why these socially bonded hybridizations occur (McKee et al, 2016). And again, we may be seeing these hybridizations in the West because genetically, the Red-eyed Vireo is slightly more closely related to the Western subspecies of Warbling Vireo than they are to the Eastern subspecies (McKee et al, 2016).

Brood Parasitism

Warbling Vireos are one of the most highly parasitized host species of the Brown-headed Cowbird (Ward and Smith, 2000). Brown-headed Cowbirds are generalist parasites that deposit their eggs in the nests of around 130 different species across North America (Barnagaud et al, 2015). Warbling Vireos have a rough time with these native parasites in the Okanagan Valley, British Columbia, suffering up to 80% nest parasitism in some populations (Ward and Smith, 2000). This is obviously a cause for concern for Warbling Vireos as the majority of nests that are parasitized produce no vireo young due to competition with the bigger and stronger cowbird chick (Ward and Smith, 2000). Warbling Vireos are a particularly ideal host species as they nest on the forest edge and are variable in their behaviour of ejecting the “bad eggs” from the nest (which is difficult to do with their small bills) (Underwood and Sealy, 2011). Warbling Vireos in the Okanagan Valley were not particularly good at ejecting cowbird eggs from their nest, while Warbling Vireos in Manitoba were more successful (which makes them the smallest bird to eject cowbird eggs – how neat is that!) (Ward and Smith, 2000). It is important to continue to monitor the Okanagan Valley populations of Warbling Vireos so we can determine if these populations are at risk of extirpation. If emigration from source populations (populations that are able to produce a surplus of offspring) to sink populations (populations that are unable to produce enough offspring on their own to avoid decline) becomes more rare, this will be a concern for local extirpation of Warbling Vireos (Ward and Smith, 2000).

If you are interested in learning more about brood parasitism and the interesting ecology of the Brown-headed Cowbird, check out Marissa Wright-LaGreca’s wonderful blog here! She does an excellent job highlighting the neatness and peculiarities of a very intriguing bird.

Concluding Thoughts

Just because the Warbling Vireo’s conservation status is alright for now, we cannot say the same for all birds. Recent research underlines the devastating reality that over 3 billion birds have been lost in North America since the 1970s. These are horrifying numbers! Contributors to this are habitat loss, window collisions, pesticide use, and outdoor domestic cats. Outdoor cats are responsible for killing around 1-3 billion birds per year in the United States alone. We all have to do our part in protecting the birds we love to watch in our backyards. Plant native vegetation in your yards, be responsible pet owners and keep your cats inside, talk to your neighbours and family members about this issue, and spread the word! You can read more about this issue here and here!

“For me, [Warbling Vireos are] one of the neatest things on this planet. That is why […] I started [this blog]. Because [I] want everyone to know just how neat [Warbling Vireos are] instead of just me […] knowing it. How neat is that? That’s pretty neat.

Adapted parody from Neature Walks, episode 1 (Vicscrappyvideos).

Literature Cited

Neville, J., and M. Coulson. 2003. Beginners Guide to B.C. Bird Song. Neville Recording. Track 41.

McKee, A.T., D. Yang, Z. Ormsby, and F.X. Villablanca. 2016. Interspecific pair-bonding and hybridization in Warbling (Vireo gilvus) and Red-eyed (Vireo Olivaceous) Vireos. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 128 (4): 738-751.

Sibley, D.A. (2000). The Sibley Guide to Birds. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hey Sam,

Fantastic blog! With such subtle markings it’s difficult to appreciate just how elegant warbling vireos are when you don’t see them up close very often. Your photos really illustrate that well, and do them justice. Thanks for sharing them!

I found it so interesting to find out about the levels of parasitism warbling vireos encounter from brown-headed cowbirds. Did the study suggest a reason why the Manitoba populations were more successful at ejecting the cowbird eggs than the Okanagan Valley population?

Hi Ally,

Thank you for your feedback, I appreciate it! It really is so much easier to appreciate the subtle nuances of bird plumage when you are as fortunate as us to see them up close in the hand! It’s among the hundreds of reasons I love my “job”!

As for your inquiry, to put it simply: I don’t know. Ward and Smith (2000) don’t specifically mention why their studied Warbling Vireo populations in the West have not kept up with the Eastern subspecies’ ability to eject the “bad eggs” of the Brown-headed Cowbird (Sealy, 1996). Comparing both studies, we have to take into account that Sealy (1996) was observing substantially fewer parasitized nests in their study compared to Ward and Smith (2000). The later study looked at a total of 58 nests with 29 accounts of parasitism, while the former observed 56 nests of which 2 were parasitized.

Besides the difference in sample size, there may also be a cost to rejecting eggs from a nest. Sealy (1996) observed the vireos using a puncture-ejection method where the cowbird’s egg was punctured with the vireo’s beak before being tossed from the nest – but this could come at the cost of the vireo possibly hurting one of their own eggs if their beak ricochets off the cowbird egg. In general, birds with smaller bills are not as successful in removing the parasite’s eggs. The idea of an evolutionary lag comes into play and may account for why smaller birds don’t eject cowbird egg’s as successfully. However, I didn’t find a study that looked at the relation of cowbird egg acceptor species size and their ability to eject the egg.

All this to say, it is really cool that Warbling Vireo’s were observed to eject the cowbird eggs, even if these observations were limited.

Here are the links to the specific articles I mentioned above.

Sealy, S.G. 1996. Evolution of Host Defenses against Brood Parasitism: Implications of Puncture-Ejection by a Small Passerine. The Auk 113 (2): 346-355.

Ward, D., and J.N.M. Smith. 2000. Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism results in a sink population in Warbling Vireos. The Auk 117 (2): 337-344.

Thank you again for your comments, I hope I managed to somewhat answer your question!

Samuelle

Hi Sam,

That was an absolute treat to read- beautifully written, engaging, and very well-referenced. I can’t believe how many of these beautiful birds you’ve seen in your banding career. The photos you’ve taken absolutely do their effortless beauty justice. However, I definitely don’t envy the person who had to come up with the ‘lyrics’ to the vireo’s song. So melodious, but quite the mouthful!

I have a question about one of the other common species of vireo. Since we’re often able to age or sex other bird species based on eye colouration, does any of that apply to the red-eyed vireo? Or are they aptly named for all having red eyes? Is there a simple way to age/sex the warbling vireos from afar since they don’t have the same eye distinction?

Again, thank you so much for sharing your knowledge of these stunning little birds. It totally makes sense that they’re what Rodney’s pal was talking about during the neature walk. Pretty darn neat!

Shenade

Hi Shenade,

Thank you very much for such encouraging feedback! I am really glad you enjoyed the beautiful Warbling Vireo as much as I did. And you are right, their song is super complex! Phonetically, their song (kind of) sounds like viderveedeeviderveedeeviderVEET, and their calls can be meeerish, meeezh, or gwit (Sibley, 2000). You are welcome to try and sound these out at home, but you may sound a little loon-y! 😉

Thank you for such a great question! Regarding the Red-eyed Vireo, you’re right! Eye colour can be helpful in aging these guys. Juvenile birds have a brown or grey-brown iris, while adults usually have the bright red eye. However, sometimes second year (SY) birds retain the brownish iris colour in the spring, and even after second year (AHY) birds may still never acquire the full red colour (Pyle, 1997). So while eye colour is usually a helpful indicator of age when you are comparing hatch year birds to anything else, it’s good to have a look at other characteristics to confirm.

Regarding the Warbling Vireo, we are a little out of luck if we wanted to attempt to age this bird in the field. For ageing these beauts we are looking at shape of primary coverts, tail shape, and we can also look at mandible lining colour (Pyle, 1997). Perhaps if you have an excellent camera and you were lucky enough to capture a photo of a Warbling Vireo with a nicely open wing, then ageing this bird in the field is certainly possible!

If you want to look into this even more, I’ll invite you to check out my sources:

Pyle, P. 1997. Identification guide to North American birds, Part I. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, California, USA.

Sibley, D.A. (2000). The Sibley Guide to Birds. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Thank you again for such an excellent question, and I hope I satiated your curiosity!

Sam

OH HECK

Great blog Sam!

It’s really cool how you took most of the visuals yourself! Makes me feel like I am reading the blog of a true expert These guys do have a nice sounding song, and it really does sound like they are asking a question. Excellent cover photo choice as well. I love that you can see the bristles near the bill in great detail!

I am curious to know if there is any reason Warbling Vireo’s in the Okanagan are experiencing such high rates of brood parasitism compared to Warbling Vireo’s elsewhere?

It is interesting how one sub-population can be in decline and another can be fine! Thanks for the informative and neat blog!

Joel

Hi Joel,

Thank you for your thoughtful comments! I’m glad you enjoyed my blog and I am happy that I was successful in sharing the neatness of this beautiful bird. I am very fortunate to have caught a couple of late season Warbling Vireos to have a photoshoot with, and even luckier to have caught more species of vireos this summer for comparison!

Thank you for your great question. Ward and Smith (2000) surveyed 27 plots of land in their study and within them, the Warbling Vireo nests tended to be in young conifer stands. These stands had been clear cut from 1979 to 1982. They also found that their nests were within 15 meters of the edge of forest habitat, and the majority of those (all but four) were even within 5 meters of the edge of forest habitat (Ward and Smith, 2000). That being said, these nest locations are particularly ideal for Brown-headed Cowbirds to come in and deposit eggs because these parasites love fragmented habitat. So I would imagine (and this is just my own speculation) that generally Warbling Vireo populations nesting in similar young (recently clear-cut) stands will suffer a higher rate of brood parasitism by cowbirds. The Okanagan Valley is a really good example highlighting this.

Studying source and sink populations is super important in conservation ecology, and I agree, it is really interesting!

I hope that helps. Thank you again for your feedback!

Samuelle

Ward, D., and J.N.M. Smith. 2000. Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism results in a sink population in Warbling Vireos. The Auk 117 (2): 337-344.

What a neat blog post!!

You obviously put an amazing amount of detail and research into this topic and presented it beautifully, not a single eye glazed over while reading this!

I’m particularly fascinated by how their songs can be influenced by others and am hoping you can expand on that for me a little. Are they influenced solely during development which affects their adult song? Once they are fully developed can their song be manipulated by neighbours or others of the same species?

Thanks Sam!!

Hi Em,

Thank you for taking a look at my blog, and I appreciate the kind feedback! I’m glad I could keep your eyes unglazed! 😉

Song development is a fascinating topic for sure. In the case of Warbling Vireos, song is learnt during juvenile development. Young male Warbling Vireos listen to and learn from their fathers and other surrounding males in their natal area to learn their song (since males generally do the singing) (McKee et al, 2016). Since vireo species can have overlapping breeding territories, these young Warbling Vireos can be exposed to the songs of other vireo species during the time of critical song development. This can influence the final (adult) song (McKee et al, 2016). Once developed, the final adult song of the Warbling Vireo is fixed, and they don’t continue to learn or add anything (James, 1976). Warbling Vireos aren’t mimics, but during the juvenile song development phase, they are highly susceptible to influences from related species, especially if the Warbling Vireos are less abundant in the area compared to another vireo species or if they have an absent father (James, 1976).

I hope that helps! Thanks again for a great question.

Samuelle

Here are some resources with lots of information on this:

James, R.D. 1976. Unusual songs with comments on song learning among vireos. Canadian Journal of Zoology 54: 1223-1226.

McKee, A.T., D. Yang, Z. Ormsby, and F.X. Villablanca. 2016. Interspecific pair-bonding and hybridization in Warbling (Vireo gilvus) and Red-eyed (Vireo Olivaceous) Vireos. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 128 (4): 738-751.