Hello, welcome here! I’d like to share with you something about one of my favorite birds which I suspect you may be familiar with: the legendary Trumpeter Swan. Trumpeter Swans are flipping amazing. To start with, they have the most epic Latin name: Cygnus buccinator (basically a gladiator name). On top of that, they happen to be the LARGEST living bird native to NORTH AMERICA, and the LARGEST waterfowl on the PLANET weighing up to 17kg with a wingspan up to 2.5 meters! (Kay, 2012) If you need any more convincing of their awesomeness, consider the fact that their population dropped to only 69 individuals in the wild in the mid 20th century and have rebounded to healthy populations again, a conservation success! (Mitchel 2010) Ironically, one of the contributing factors to their happy return is they appear to be one of the lucky few who are benefiting from climate change: expanding summer ranges! Survival of the giant bugling white mammoth water bird!

Description/ identification:

If you live anywhere from the far Pacific northwest to the lower US Midwest, you’ve likely seen these graceful giants resting in open farmers fields or along ice-free waterways in the winter, or heard their distinctive French horn bugle as they migrate their way north or south in a staggered flight pattern. Their large body size and entirely white plumage are unmistakable, along with their deep black eyes and large black bill and legs in mature individuals.

Other possible species that could potentially be miss-identified as trumpeter swans include the tundra swan, mute swan, and the snow goose. Tundra swan and trumpeter swan, although visually very similar, historically have inhabited separate geographical regions and therefore are typically not misidentified. However, this may become more likely as summer ranges of the trumpeter swan continue to increase northward into the habitat of the tundra swans. Luckily the isolated black eye in white plumage, concave shape of the bill, and the distinctive yellow lore of the tundra swan can be used to distinguish them from Trumpeter Swans. The Mute Swan, a species originally from Europe and introduced to North America, differs from the Trumpeter Swan by the orange color of its bill and knob on its forehead. Although not a Swan, occasionally the snow goose could be confused with the Trumpeter Swan but can be easily distinguished by its pink bill and much smaller size (Kiley 2018).

Distribution:

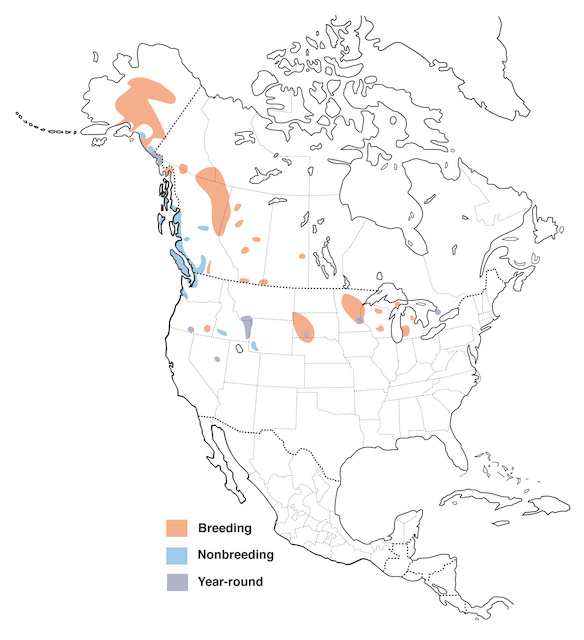

Trumpeter swans are typically either permanent residents or medium distance migrators. For the migrating populations, their summer breeding grounds range from pockets in the Midwest and central/northern BC to vast tracks in northern Alaska. The migrating birds from the Alaskan coast typically winter over in the temperate Pacific Northwest, while migrating populations from the Alaskan and BC interiors typically winter over in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. Non-migrating populations of Trumpeter Swans lay scattered in the inter-mountainous regions throughout the west. (Mitchell. 2012)

Habitat:

Trumpeter Swans usually prefer shallow undisturbed freshwater with lots of aquatic vegetation to feed on. Because of their huge size and high aspect ratio wings, Trumpeter swans need at least 90 meters to take off into flight. This, therefore, restricts their ability to live in thickly wooded regions or small ponds surrounded by tall vegetation. Pairs mate together year after year in the same nest, which they often hijack from muskrats or beavers’ dens on rises of land in shallow waters (Mitchell et al 2010).

Conservation:

As mentioned previously, Trumpeter Swan populations experienced a major decline from the 1600s to the 1800s, mostly due to hunting pressures from humans. At one point there were as few as 69 individuals remaining in the wild. Although populations have increased drastically since then and are currently considered not threatened, conservation biologists are concerned about the possible founder effects on the existing population due to having experienced a genetic bottleneck.

Trumpeter Swans are generally considered a classic conservation success (Mitchell 2010). This is largely due to groups of conservationists and volunteers dedicated to preserving this species. An example of one of these groups is the TTSS (The Trumpeter Swan Society) which is a group of volunteers and donors whose mission is to ensure the vitality and welfare of Trumpeter Swans. Since 1969, the TTSS has held a biennial conference where swan conservationists come from around North America to share recent relevant research and promote a strong “Swan network” across North America (Trumpeter, 2019).

Research:

Much research is currently being conducted into the Trumpeter Swan populations across North America. A current ongoing area of research on Trumpeter Swans is improving our understanding of migratory routes and migrating habits of metapopulations around the American Midwest. Scientists are using GPS tracking devices attached to cygnets (juveniles) to provide real-time tracking of individuals for up to three years. A hotspot of current research is in southeast Idaho where there is a particularly high rate of cygnet mortality and low rate of return for second-year cygnets after their first migration. Having a more accurate understanding of migrating habits will enable us to understand what geographical areas need to be protected to preserve these populations (Iowa State Uni 2019)

An additional area of study is the monitoring of Trumpeter Swan egg temperature in the Yellowstone ecosystem in Grays Lake National Wildlife Refuge in Idaho, USA. Biologists with the Western Oregon University are studying the effect of egg temperature on cygnet survivorship to pinpoint factors contributing to low survivorship. They hypothesize that egg temperature variance of ± 2° degrees from the ideal 39° C would result in decreased egg vitality and ultimately decreased cygnet health and survivorship. To test this, the researchers placed temperature probes into artificial eggs that were placed in Trumpeter Swan nests. When the eggs hatched the data collectors were retrieved and the results were analyzed using computer software. The data loggers were also put in an incubator for 4 weeks as a baseline negative control. Although the results were preliminary and needing further study with larger group size to support their findings, they demonstrated that the mean egg temperature was beneath the hypothesized optimal incubation temperature, and that increased frequency of recesses (drops in temperature bellow 2 degrees from the mean) resulted in lower fledgling rates (Snyder et al 2018).

I hope this has been educational and interesting for my readers! If nothing else, I hope that you may take away from this an appreciation for the magnificent birds that temporarily bless us with their presence as they pass through on their way to greener pastures.

References:

- Iowa State University: Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management. 2019. Accessed on Oct 31st, 2019. https://www.nrem.iastate.edu/track-trumpeter

- Kay, Jane; 2012. Trumpeter Swans Rebound, with an Assist from Global Warming. The Daily Climate. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/trumpeter-swans-rebound-assist-global-warming/

- Mitchell, Carl D.; Michael W. Eichholz. 2010. Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator), life history. All about birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Trumpeter_Swan/lifehistory

- The Trumpeter Swan Society. 2019. Date accessed: Oct 31, 2019. https://www.trumpeterswansociety.org/who-we-are/

- Roth, Kiley; 2018. 4 WAYS TO TELL APART SWANS AND SNOW GEESE, https://dickinsoncountyconservationboard.com/2018/04/09/4-ways-to-tell-apart-swans-and-snow-geese/

- Snyder, Jeffrey W.; Fliehr, Victoria B.; Long, Bill. 2018. Trumpeter Swan Egg Temperatures (Cygnus buccinator) in Relation to Cygnet Survivorship at Grays Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Idaho, USA. Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=fac_pres

Hi Kevin,

Interesting blog. I do love seeing Trumpeter Swans in the winter, they are noisy but elegant beasts! Keep an eye out in your fields for Tundra Swans, they do show up! You just have to look really thoroughly.

You mentioned in your blog that “conservation biologists are concerned about the possible founder effects on the existing population due to having experienced a genetic bottleneck.” Can you elaborate on that? Have researchers noted major negative outcomes due to this founder effect, like disease susceptibility or anything else? With only 69 individuals left in the wild, it seems like there would be some kind of genetic consequence. You say that they are considered a conservation success, so maybe these birds were very lucky to have avoided any serious damage due to low genetic variation?

Thanks for sharing your love for Trumpeter Swans!

Samuelle

Thanks for your comment Sam!

By bottleneck event I am referring to the term evolutionary biologists use to describe a drastic reduction in genetic variability in a population due to a reduction in population size. Although the population may recover to healthy numbers, the genetic variation in the recovered populations has basically the same genetic variability as in the few survival members who go on to reproduce. Genetic variation in a population provides the raw material on which natural selection will operate to allow species to respond to changes in their environment, to evolve. Decrease genetic variability due to founder events results in decreased resiliency in a species to cope with changes and increases the rate of genetic drift, which are changes due to random chance.

That said, I didn’t come across any specific examples of negative effects to Trumpeter swans as a result of these issues. Although genetic relatedness and outbreed/inbreeding coefficients can be calculated on swan populations, the ultimate effects of these factors on swan survivorship may only become apparent if and when unforeseen changes affect these animals negatively.

I haven’t found any current studies assessing the genetic relatedness of Trumpeter Swan populations. This would be critical information to ultimately assess the health of Trumpeter Swans in North America.

Cheers!

Hi Kevin,

I can really tell how passionate you are about these birds after reading your blog, and that enthusiasm is definitely infectious!

You mentioned that Trumpeter Swans are monogamous, and return to the same breeding site repeatedly. Are they seasonally monogamous or do they mate for life?

Thanks,

Sarah

Hi Kevin,

Nice blog! I can tell this is a favourite bird of yours. I had no idea that Trumpeter Swans were so big, that is definitely cool.

I was wondering about mating behaviors, and you briefly mentioned they engaged in monogamy. Mute Swans are famous in part for their “noisy but elegant” courtship behaviors. Do you know if there is any specific mating behaviour associated with Trumpeter Swan pairs?

Thanks!

Merissa