Natural History

Mallards are one of the most abundant ducks in the world, and likely the most familiar to passesby. The male Mallard has an iridescent green head and a dark brown breast separated by a thin white collar around the neck. Males in non-breeding plumage lose the identifying colours of their feathers but can still be identified by their bill colour. Females have orange and brown bills and mottled brown feathers. Both sexes can be identified by their speculum, a patch of feathers on the wing that’s visible during flight, which is iridescent blue with a white border (Allaboutbirds.org 2017).

Female (left) and male (right) Mallard

Photo: WildlifeNYC

Male Mexican Duck

Photo: Ryan O’Donnel

Male Mallard X American Black Duck hybrid

Photo: Gordon Johnston

Mexican Ducks are thought to be a subspecies of Mallard, but genetic evidence indicates they are more closely related to the American Black Duck. Instead of a pronounced difference between males and females, both genders are mottled brown like the northern female. Mallards will also hybridize with other duck species, like the American Black Duck, which creates a blend of colourations and patterns (Neotropical.birds.cornell.edu 2019).

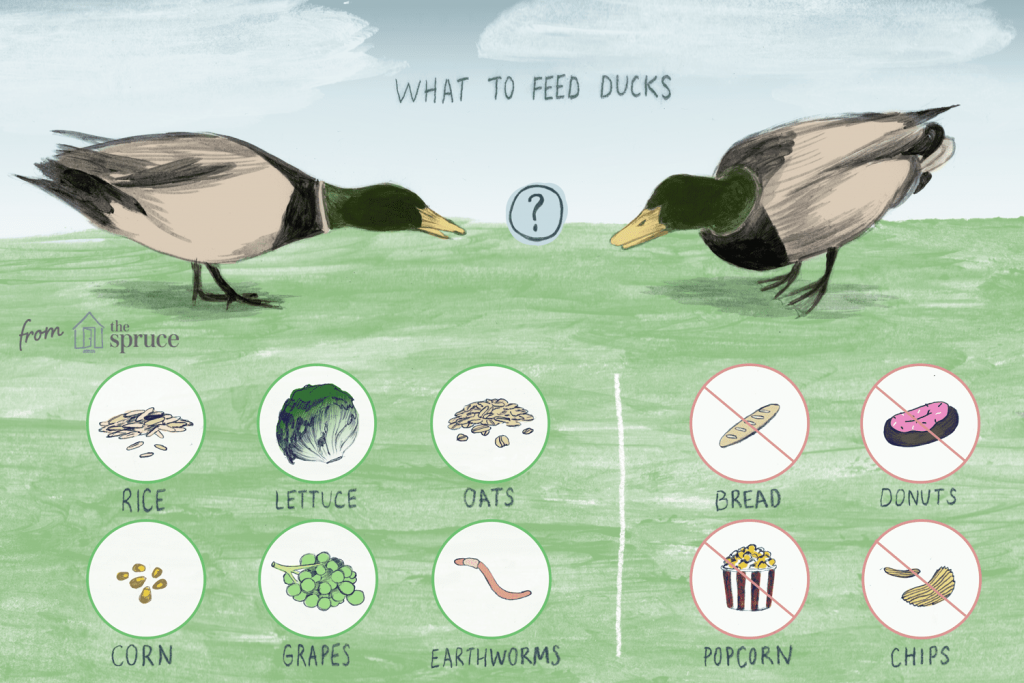

Mallards are dabbling ducks, submerging the head and neck while upending to probe the mud for food. They have an omnivorous diet consisting of seeds, roots, and grasses, as well as insects and small aquatic vertebrates. Mallards will also graze on land for these foods (Audubon.org 2019). They will also accept food from people at duck ponds and city parks. People commonly feed bread to wild ducks, which doesn’t provide the variety of nutrients present in their natural diet. As a substitute for bread, consider feeding ducks peas, corn, grains, seeds, or lettuce instead (Allaboutbirds.org 2017).

Male Mallard dabbling

Photo: Karen VK

They are widespread and common in the northern hemisphere, particularly in America, Canada, and Europe. Click here to see an interactive map of Mallard distribution. Some Mallards that breed in northern Canada and Alaska will migrate to the southern United States to over-winter. Others do not migrate and can be found year-round in most of America and coastal British Colombia (Audubon.org 2019). Mallards will live in most wetlands, both natural and artificial, from lush marshes to roadside ditches . Mallards are the most heavily hunted duck, estimating a third of all ducks shot in North America (Allaboutbirds.org 2017). The Mallard is not considered at risk, but the current population trend is decreasing (Nationalgeographic.com 2019).

Mallard chicks

Photo: Jen Goellnitz

Mallards will migrate once they have formed a breeding pair. A variety of courtship behaviours are used to establish pairs, including head-bobbing (seen in the video below), swimming quickly with the head lowered to the surface of the water, and, in males, whistling while circling a female (Allaboutbirds.org 2015) They nest on the ground or in protected cavities, and build nests out of sticks, grass and down (Nationalgeographic.com 2019). A nest will typically have between 1-13 cream coloured eggs, but on one occasion a female was observed associating with 29 ducklings. This extreme case be be the result of brood parasitism, when females will lay their eggs in another female’s nest (Seabrook-Davison, 2014).

Mallard nest

Photo: Greg Munson

Although conspecific brood parasitism (CBP) sounds awful (raising 29 ducklings is a hard job!) the negative effects on the parasitized female are typically quite low, and is fairly rare in Mallards. It’s estimated that CBP occurs in 0-10% of nests. Parastic females may choose a nest based on easy detectability and quality of the nest, or nesting female (Kreisinger et al, 2010). Parasitized nests tend to have fewer eggs than average, even after a second female has laid in them. This keeps the burden on the parasitized mother from growing too large, thus mitigating possible negative effects (Lokemoen, 1991). When broods do become large, som consequences include decreased hatching success, increased incubation period, and increased risk of abandonment by the mother (Kreisinger et al, 2010).

Males will abandon the nest once the eggs have hatched, leaving the female to care for the offspring. Ducklings are ready to leave nest within 13 hours of hatching. The young know how to swim as soon as they hatch and can feed on their own while the mother leads them between the nest and feeding grounds (Allaboutbirds.org 2017).

Mating Behaviour and Genital Morphology

Copulation in Mallards has been studied for many years and is still being studied today. Birds typically have simple genitalia, with males lacking external genitalia and females having simple vaginas. Waterfowl, including mallards, are the only birds that have a penis. A Mallard’s penis is corkscrew-shaped and is coated in ridges and spines (Brennan et al, 2007). The length of the phallus, the size of the testes, and the amount and size of ridges and spines all increase when forced copulation is common (Coker et al, 2002). The phallus is stored in a sac inside the body until it is everted. Eversion of the phallus has been termed “explosive,” with the phallus becoming fully erect within a third of a second (Brennan et al, 2009). Because Mallards typically copulate while swimming, using an intromittent organ like a penis may ensure that sperm are delivered to the female and not lost in the water (Coker et al, 2002).

Penis (top) and vagina (bottom) of the Mallard

Photo: Patricia Brennan

Female Mallards have corkscrew-shaped vaginas that turn in the opposite direction as the penis. This creates a mechanical barrier that makes full eversion of the penis difficult (Brennan et al, 2009). The vagina also has two different types of pouches. The first type of pouch is found near the cloaca, and likely act as “dead-ends” for the phallus, which can prevent sperm from reaching the egg. Sperm deposited in these pouches may even be ejected by the female. The second type of pouch is found closer to the utero-vaginal junction and is used for storing the sperm of successful males for fertilization. (Brennan et al, 2007)

An unfortunate female / Photo: Africa Gomez

Forced copulation is common in waterfowl, which causes conflict between the sexes. Older literature describes this behaviour by males as “rape”, but modern literature prefers to use “forced copulation” to avoid the use of the controversial term. Such behaviour is recognized by active pursuit, grasping, and overpowering of a female by a male. Many males have been observed pursuing a single female, and this aggressive behaviour may even lead to the death of the female. Pair copulations, in contrast, involve characteristic mating displays performed by both sexes (Burns et al, 1980). It has been shown that high testosterone levels will contribute to higher rates of forced-copulation attempts (Ellen S. Davis, 2002a).

The antagonistic morphology present in Mallards likely coevolved as a method for females to control fertilization by unwanted males. (Brennan et al, 2007) Pairs are established weeks or months before migration to the breeding grounds, and a female will not solicit extra-pair copulations. (Brennan et al, 2009) Females may choose mates based on the ability to defend against other males. In a study by Davis (2002b), females that paired to males with high testosterone, and presumably were more active in protection, were missing less feathers from forced copulation attempts.

References

- Audubon.org (2019) Mallard, National Audubon Society.

- Allaboutbirds.org (2017) Mallard, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Nationalgeographic.com (2019) Mallard, National Geographic Society.

- Seabrooke-Davison, M (2014) Observation of a female mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) with 29 ducklings. Notornis, 61: 51-53

- Allaboutbirds.org (2015) How to recognize duck courtship displays, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Neotropical.birds.cornell.edu (2019) Mexican Duck, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Kreisinger, J., Munclinger, P., Javurkova, V., Albrecht, T. (2010) Analysis of Extra-Pair Paternity and Conspecific Brood Parasitism in Anas Platyrynchos using non-invasive techniques. J. Avian Biol., 41: 551-557. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-048X.2010.05002.x

- Lokemoen, J. T. (1991) Brood Parasitism among Waterfowl Nesting on Islands and Peninsulas in North Dakota. The Condor, 93(2): 340-345

- Brennan, P. L. R., Prum, R. O., McCracken, K. G., Sorenson, M. D., Wilson, R. E., Birkhead, T. R. (2007) Coevolution of Male and Female Genital Morphology in Waterfowl. PloSONE, 2(5): e418 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000418

- Coker, C. R., McKinney, F., Hays, H., Briggs, S. V., Cheng, K. M. (2002) Intromittent organ morphology and testis size in relation to mating system in waterfowl. Auk, 119(2): 403-413

- Brennan, P. L. R., Clark, C. J., Prum, R. O. (2009) Explosive eversion and functional morphology of the duck penis supports sexual conflict in waterfowl genitalia. Proc. R. Soc. B, 277: 1309-1314 doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2139

- Burns, J. T., Cheng, K. M., McKinney, F. (1980) Forced Copulation in Captive Mallards I. Fertilization of Eggs. Auk, 97: 875-879

- Ellen S. Davis (2002a) Male reproductive tactics in the mallard, Anas platyrhynchos: social and hormonal mechanisms. Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 52: 224-231 DOI 10. 1007/s00265-002-05 1 3-z

- Ellen S. Davis (2002b) Female choice and the benefits of mate guarding by male mallards. Animal Behaviour, 64: 619-628 doi:10.1006/anbe.2002.3079

Hi Sarah,

Nice blog! I love the video at the end – Ze Frank will always be hilarious. I was lucky enough this summer to stumble upon a Mallard’s nest while I was clearing net lanes. I flushed the poor mum, but what a cute nest on the river’s edge. I think there were nine eggs!

I love the precocial little chicks; baby passerines are cute, but baby ducks are CUTE! In the video, Ze Franks says that a duck’s penis withers and falls off after the breeding season, it that true for all duck species in general, including the non-migrating populations of Mallards? What about the females, do their reproduction organs shrink before migration, and return more complicated and with new/more “dead ends” the next breeding season? It’s also really interesting that these guys have courtship behaviours and displays even though forced copulation is common.

Thanks,

Samuelle

Hi Sam,

All the literature I’ve read seems to use “ducks” as a general term, so I would assume that all duck species have the ability to lose, or at least reduce, the size of their penis after the breeding season. As for non-migratory Mallards, I couldn’t find a conclusive answer. I guess it would depend on the energetic cost keeping the penis compared to the cost of regrowing it.

There is significantly less information on female genital morphology, so I was unable to find a conclusive answer to those questions. If I had to take an educated guess, I’d say it would make sense for the female’s reproductive organs to shrink after the breeding season to conserve weight. If this was the case, it would be interesting to see if new pouches grew in relation to the frequency of forced copulation a female experiences.

Here’s a couple links to some more reading that I found related to your question, if you’re interested:

https://doaj.org/article/093253b6952a41d795f5400d184a4d8e

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2017/09/duck-penis-size-social-group-study/

Hi Sarah!

Great article! I’m not sure about you, but I’ve definitely found a greater appreciation for these guys after watching them for so long in Animal Behaviour! I was curious about the brood parasitism mentioned. Were you bale to find anything that mentioned if female mallards were able to identify the parasitic egg or if they had any method of dealing with the resulting larger clutch size?

Again, very interesting blog!

Thanks,

Gen.

Hi Gen,

It seems that Mallards are unable to differentiate parasitized eggs from their own. The negative effects of brood parasitism in Mallards is generally low because parasites typically target nests with less eggs. In extreme cases, however, the large brood can result in decreased hatching success, prolonged incubation period, and increased chance of abandonment by the mother.

I found so much cool information on brood parasitism that I might add a couple more paragraphs on it to my blog!

Hi Sarah.

I really enjoyed reading your blogs and well it was a mix of well-researched cuteness and shocks!

I did not know there is a brood parasitism within the species and such harsh competition among the males. Their ability to copulate underwater is definitely the most intriguing part to know about, and no wonder they get such long penis.

I noticed there are so many duck species similar to Mallards. However, do you have any idea what traits make them so dominant and abundant in North America or even the world? Is it because we feed them?

Hideki

Hi Hideki,

Mallards are thought to be so common because of their adaptability to different environments, tolerance of human activity, and varied diet. Being hand fed by humans probably helps them too, especially in winter when food is less common. Their huge range may be due in part to domestication and transport to new areas by humans. Fun fact: All domestic duck species, except the Muscovy Duck, are relatives of the Mallard!

Thanks for the question!

Hey Sarah, very interesting article. You mentioned that the size of the phallus and testes increase when forced copulation is more common, is that purely from the increased testosterone that apparently increases forced copulation rates or do you know if there is other biochemical factors that affect that, and does rate of forced copulation purely increase out of chance or is there maybe other factors that increase it, such as increased competition for mates or less prospective mates for males within the population?

Thank you for your time,

John H.

Hi John,

Testosterone and the frequency of forced copulation within a species is one of the most important factor in determining phallus size in ducks. I couldn’t find any other hypotheses as to why testis and phallus size differs between species, but it’s always possible that there’s some other mechanism we haven’t thought of yet. Frequency of forced copulation is related to high testosterone. Any factor that increases testosterone, such as amount of surrounding males, acquisition of a mate, or even captivity, can in turn effect the rate of forced copulation.

Thanks for the question!

Hi Sarah,

Great blog! It looks very professional and your information was very interesting! I liked the video at the end 🙂

We observed quite a bit of courtship behavior when we observed these ducks for animal behavior this fall. You mentioned pairs are established weeks/months before migration. Do you know why pairing and courtship is displayed so far from breeding season? Does this strengthen the bond/reduce forced copulation in any way?

Thanks!

Merissa

Hi Merissa,

I loved watching the Mallards bob their heads in courtship! It’s such a simple gesture but its pretty cute.

Mallards begin to concentrate at staging grounds in fall to prepare for southward migration. Although pairing and courtship behaviour peaks in winter and early spring, it can begin as early as fall before migration. Because competition for mates is so fierce in Mallards it pays for a male to pair with a female early. Early pairing also allows females more time to assess mates, and lets a pair start breeding as soon as they arrive on the breeding grounds in the following spring. Like many duck behaviours, early pairing is unique, with other seasonally monogamous birds delaying pairing until spring.

This article has a lot more helpful information: https://www.ducks.org/conservation/waterfowl-research-science/understanding-waterfowl-courtship-and-pair-bonding

Hi Sarah!

Great blog! I love ducks and their quacks make me laugh (mostly because it sounds like they’re laughing, too)!

I was wondering if there have been observed instances of interspecific brood parasitism and whether the females notice and raise the other species young as her own? I was also wondering if you have heard of cases of females “adopting” other mallard ducklings and if cases of large broods were mostly from brood parasitism or these “adoptions”.

Thanks!

Melissa

Hi Melissa,

Yes, interspecific brood parasitism has been recorded, and it seems to be just as common as conspecific brood parasitism! It’s thought that brood parasites will seek out the most accessible, yet still compatible nests rather than a specific host. Mallards have been observed adopting other Mallard chicks, especially if the hen has chicks of her own that are the same size as the adopted ones. I wasn’t able to find any information on interspecific adoption in Mallards, but it may be possible if the chicks look similar enough for the hen to mistake the chicks for Mallards. I found one instance of interspecific adoption with a pair of Common Loons and a Goldeneye duckling. The reason for the adoption may have to do with Loons not being able to identify individual chicks, and being hormonally primed to care for chicks during the breeding season.

Thanks for the question! Here’s a couple of interesting articles on the topic if you’re still curious:

https://www.insider.com/duck-adopts-abandoned-ducklings-2018-6

https://www.audubon.org/news/a-pair-common-loons-adopted-lucky-goldeneye-duckling-and-it-was-big-deal

https://www.audubon.org/news/heres-why-mama-merganser-has-more-50-ducklings#