Part 1: Introduction to the Dark-Eyed Junco

DESCRIPTION AND IDENTIFICATION

The Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis) is one of the most abundant birds in North America (Bailey et al., 2017) with recent estimates suggesting the entire population is somewhere around 630 million individuals (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019). This passerine (order Passeriformes) is part of the family Passerellidae also known as the New World Sparrows (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019). Often recognized by its burglar-like appearance here in BC due to its conspicuous black hood, the colouration of Dark-eyed Juncos actually varies greatly with geographical location; so much so that 5 out of the 6 recognized forms were considered different species until the 1980s (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019). Although the plumage pattern of juncos differs depending on their location, juncos are generally dark-grey or brown in colour. Despite this variation in plumage, it is easy to identify a junco based on their flashy white outer tail feathers that are easily spotted while they’re in flight (McGlothlin et al., 2007), as well as their light pink bill.

If you were to take a walk through the woods at this time of year, you would likely hear the soft chirps of local Dark-eyed Juncos as they wander through the brush, possibly trying to encourage other juncos to follow.

Male juncos across the different subspecies typically have repertoires of 2-8 song types, and are often slightly improvised or modified by the individual (Reichard, 2014). During breeding season, male juncos don’t rely solely on their plumage to attract and stimulate potential mates, songs play an important role in mate selection. The advertising song of a junco is usually a single trill, consisting of a single pitch (Audubon, 2019).

Certain calls given by the dominant male junco are used as aggressive warnings for other male juncos to essentially “back off” (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019). Some studies have shown that despite similarities between the 6 recognized subspecies’ calls, male juncos actually respond more aggressively to the trills of other local males rather than an almost identical call from a junco of a different geographical location (Reichard, 2014).

DISTRIBUTION

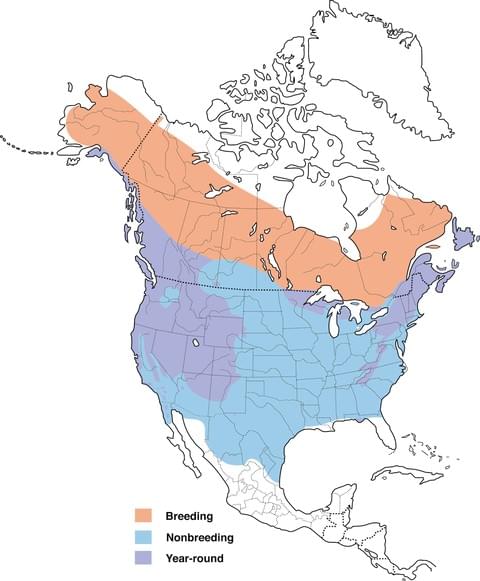

With a rapid radiation through North America since the last glaciation (Reichard, 2014), dark-eyed juncos are found in nearly every corner of the continent, from Alaska to Mexico and BC to Nova Scotia.

Fondly called the “original snowbirds of middle latitudes,” many Dark-eyed Juncos in the US leave the mountains in which they inhabit throughout the breeding season for a slightly milder winter in the Eastern United States (Audubon, 2018). Some juncos do stay year-round, while others just over-winter.

HABITAT AND NESTING LOCATION

No one has ever accused the Dark-eyed Junco of being overly picky about its habitat. This is likely because juncos can be found inhabiting coniferous forests (pine, Douglas-fir, spruce, and fir), deciduous forests (aspen, cottonwood, oak, maple, and hickory), open woodlands, fields, parks, gardens and even roadsides all throughout North America (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019).

This lack of fuss over habitat carries over into their selection of nest sites as well. Typically, juncos are ground-nesting birds (among roots, in rock crevices, at the base of vegetation, etc.) but they can also nest in taller vegetation such as trees, and even man-made structures such as buildings, window ledges, planter boxes and even hanging flower baskets (Bailey et al., 2017).

BEHAVIOUR

Dark-eyed Juncos are primarily socially monogamous birds, meaning that they tend to stick to one mate (Rice et al., 2013). During courtship, the male engages in a short-range song directed at a specific female (Rice et al., 2013) as well as proudly displays his tail whiteness. Tail-whiteness is an attractive trait to female juncos and could represent a male bird with a better diet (McGlothlin et al., 2007).

After a successful courtship, the female chooses the nesting location and builds the nest, while the male valiantly defends the area, chasing off intruders and angrily chirping at any disturbances (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019). The incubation period is typically 12-13 days and clutch sizes range between 3-6 eggs, each less than an inch in length (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019). Following current household gender-equality ideals, the male shares approximately half of the responsibilities during the nestling stage (Liebgold et al., 2013). Throughout this time, the recently hatched young are extremely dependent on their parents. After 9 days of being fed primarily insects, the young are capable of leaving the nest, but are often still reliant on their parents for up to 3 weeks. (Canadian Wildlife Federation, 2020).

This almost sassy bird spends its time fluttering among the underbrush, confidently hopping and running along the ground in search of seeds and insects. During breeding season, juncos primarily feed on insects and can often be seen in pursuit of a fresh arthropod victim (Canadian Wildlife Federation, 2020). In the winter, juncos can be viewed pecking or scratching at the ground litter in search of seeds which make up the bulk of their diet (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019). Migratory birds such as the Dark-eyed Junco often display this shift in diet-preference and food intake in order to store up fat (Holberton et al., 2006).

Dark-eyed juncos often create flocks in the winter in which multiple subspecies may be found and a distinct hierarchy is formed (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019).

CONSERVATION STATUS

Dark-eyed Juncos play important roles in many ecosystems across North America as both agents of seed dispersal and regulators of insect populations (Canadian Wildlife Federation, 2020). Although populations are currently abundant and widespread, the North American Breeding Bird Survey suggests a yearly 1.4% decrease between 1966 and 2015 which resulted in an overall 50% decline in population (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019).

Not only are these juncos important in ecosystems, but they also provide good scientific models due to their abundance as well as their known behaviour patterns (Holberton et al., 2006; Reichard, 2014).

Dark-eyed Juncos provide functional aspects of both ecosystems and research, but maybe one of their most fundamental roles is the bringing of joy. As one of the most common birds found in North American bird feeders (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019), bird enthusiasts can gain endless amounts of fascination and intrigue just by simply viewing them.

Part 2: The Effect of Immune System Activation on Reproductive Success

All birds, including Dark-eyed Juncos, have three very energetically demanding types of behaviours throughout their lives: moulting, migration and reproduction. Often these events are timed so that they don’t overlap in order to increase the likelihood that the bird will survive another year, but not all energetically costly events can be so easily controlled (Graham et al., 2017). If these energy-depleting events occur simultaneously in an individual, the bird will likely resort to trade-offs in which priority is placed often on the behaviour that will more likely lead to survival (Graham et al., 2017). Some researchers decided to explore this effect of trade-offs in energetically expensive activities in Dark-eyed Juncos, specifically the trade off between an immune response and reproductive effort (Graham et al., 2017).

Over the course of two years, researchers scoured the area around Mountain Lake Biological Station (MLBS) in Virginia in search of Dark-eyed Junco nests (Graham et al., 2017). The nests that they discovered were checked daily in order to track the start of the incubation period (Graham et al., 2017). On day six of incubation, the mothers were captured using a mist net and injected with either a mild antigen or saline solution (as a control) (Graham et al., 2017).

The researchers found a significant correlation between the juncos injected with the mild antigen and the nest survival rate 6 days after hatching with 62% of hatched control nests surviving more than 6 days, while only 21% of the immune-responders (Graham et al., 2017). At the time of hatching the mothers injected with the antigen would have a spike in their immune response, which would likely lead her to try to conserve her energy (Graham et al., 2017). This attempt by the mother to ensure that she survives into another reproductive season may make her less available for the high-energy activities required for raising a young nestling, and could therefore decrease the chances of offspring survival (Graham et al., 2017).

A similar study was done by another research team but this time they tried to determine whether or not inducing an immune response before breeding would delay the onset of breeding activities (for example egg production) (Needham et al., 2017) Earlier-breeding individuals tend to have higher offspring survival rates, but in order to breed early the mother must start developing the yolk as well as undergo the final maturation of the follicle in the spring when resources are still sparse (Needham et al., 2017). If the mother is exposed to an antigen at this time, another trade-off is likely to take place.

Initially there was no difference in the mass, fat score or skeletal sizes between the control group and the experimental group, yet the experimental group laid their eggs 8 days after the control group on average (Needham et al., 2017). This delay in reproduction is likely due to a prioritization of the mother’s personal health over the creation of the next generation.

These studies show that even the smallest of disturbances (such as a mild antigen) before or during reproduction can lead to energetically costly behaviours that can lead to a decrease in reproductive success. Since Dark-eyed Juncos are so prevalent across North America, they provide excellent models for experiments such as these, whose results can hopefully be applied to other species who may be more ecologically threatened. Hopefully research like this can lead to solutions that can be applied to attempt to increase the nesting success of not only Dark-eyed Juncos, but many other more at-risk species.

CONCLUSION

Dark-eyed Juncos are one of the most prevalent birds in North America, and they can provide inspiration and intrigue to bird-watchers across the continent. Despite their burglar-like appearance the only thing they are likely to steal is your heart.

References

Audubon (2019) Guide to North America’s Birds. (Internet): https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/dark-eyed-junco

Audubon (2018) Juncos are the Original Snowbirds. (Internet): https://www.audubon.org/news/juncos-are-original-snowbirds

Canadian Wildlife Federation (2020) Dark-eyed Junco. (Internet): https://cwf-fcf.org/en/resources/encyclopedias/fauna/birds/dark-eyed-junco.html

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology (2019) All About Birds: Dark-eyed Junco. (Internet): https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Dark-eyed_Junco/overview

Hi Maddy,

Lovely blog! I especially love your progression photos of the ORJU nest! Very precious little babes!! Did you get to watch the adults building the nest and coming to feed the young? Nesting behaviour is fun!

I liked all the images comparing subspecies of DEJU, they are so variable! You mention that in the winter, there is a distinct hierarchy between the different junco subspecies. Can you elaborate on that? What does the hierarchy look like?

The research you looked into is really interesting. It makes sense to read, that a greater immune response is like increased stress leading to decreased nesting and successful clutches. One thing I noticed was that you mention how there was no difference in skeletal sizes between the control and experimental groups in the second study. What exactly does that mean? Surely they didn’t expect their skeleton to shrink/grow?

You nearly had me in tears with your last comment They really are sweet enough to steal our hearts!!

Thanks for a lovely read!

Cheers,

Sam

Thanks for the comment Sam!

I did get to see them bringing materials for the nest, and returning to feed the young once they hatched. It was a super special experience. I tried to stay out of the way as much as possible but every couple days I would try to sneak a picture, the mom eventually got used to me and would perch on a nearby tree letting out a few little chirps. It was super fun to watch all the action!

The hierarchy in the flocks isn’t necessarily determined by which subspecies, but actually which members have been there the longest! The birds who have been part of the flock longer tend to be near the top of the hierarchy, while more recent additions tend to be closer to the bottom.

I mentioned the skeletal size (and so did the experimenters) just to show that the delay in egg laying between the experimental and control groups wasn’t due to the overall size of the birds (such as skeletal size or body mass) before the experiment, but due to the induced immune response being a type of stress. Hope this answers your question!

Thanks for reading!

Maddy

Hi Maddy,

I really enjoyed your blog and learned so much more about Juncos! You mentioned how there is a possibility that females create sexual selection pressures for males to have white tail feathers and that the whiter they are the better the diet. My question is would it be the amount of food the Junco is consuming or just the type of food that qualifies as a “good diet”.

It was really interesting to see the effect introducing an antigen to the mother has on the length it takes for them to lay the eggs as well as the likelihood for the chicks to survive.

Another question I have is to do with the flock hierarchy; does the top of the hierarchy just lead the flock or are there any other roles these senior birds play?

Great job on the blog thanks for sharing these cute little guys with us!

Keely

Hi Keely,

Thanks for reading my blog!

To answer your first question, one experiment tested this out and compared 2 groups of juncos, one fed with just seeds to simulate times when insects were unavailable, and the other was fed the same seed diet in addition to high protein material (dog chow, boiled eggs, carrots and turkey) and both groups were able to eat as much as they desired. They found that the birds with the more enriched diets had larger and brighter tail white-spots, suggesting it’s the quality of the diet not the quantity. If you want to read a little more about this experiment you could check out the experiment here: https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/stable/27823519?pq-origsite=summon&seq=4#metadata_info_tab_contents

To answer your second question, the impression I got was that most social birds that flock together have a hierarchy so that the group can stay stable. If there is no hierarchy in which the bird knows its place among the flock then there is the risk of two birds fighting for dominance, so I think the hierarchy is a way to avoid this. Hope this helps!

Glad you enjoyed reading,

Maddy

Hi Maddy,

I really enjoyed reading this blog. I especially enjoyed the array of photos and media that was included, they were all fascinating to go through. I didn’t realize that such a common species could be so special. I had a few questions but other people already asked and you answered them wonderfully. I do still have one quick question, you mentioned how the species has been declining 1.4% per year. Would habitat loss be a big factor in this or would it not affect it so much considering they are so adaptable in finding nesting locations.

Thanks again for the fun read,

Eden

Thanks for reading Eden,

In the research I did, it wasn’t entirely clear what was causing the 1.4% decrease, it’s probably a combination of many factors and since the Dark-eyed Junco population isn’t under any serious threat I’m sure that most research is focused elsewhere. If you go to this website: (https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/dark-eyed-junco) and click on “Climate Vulnerability” there is actually an interactive map in which you can click on different temperature changes and see how it affects the possible range of DEJU. I’m sure this global warming-caused loss of habitat would play a part in their population decrease, and this map is a great way to visualize it!

Glad you enjoyed my blog!

Maddy

Hey Maddy,

Really nice blog post, very thorough! I was excited to read this as I often see them on my walks. I had a couple of questions for you:

1. I noticed you mentioned that the males would be more aggressive to varied calls from local males vs nearly-identical ones from less local juncos. How can the birds tell? Is it just from the diversity in the call that is developed between males? Why is the diversity in call developed?

2. The research you found was very interesting, though pessimistic. Are there any positive things found yet about things we can do to help the dark-eyed junco?

Cheers,

Kiera

Hi Kiera,

To answer your first question, the male DEJUs respond more aggressively to the calls of local birds due to slight variations in their dialects due to different geological locations. Even though we might not be able to hear the difference, the birds can pick up these tiny variations and respond accordingly.

To answer your second question, probably the best things the average person can do to help these little guys is to make sure your cats stay indoors, or make sure all your windows have markings or something to try to help reduce collisions.

Thanks for reading!

Maddy