Part I: Introduction

While out on a walk, looking through your binoculars, you gaze up into the canopy where you hear a group of birds chirping. You come across a red bird with a very strange feature. It looks like a finch, but what happened to its bill? No the bird did not get into a fight, or fly face-first into a tree, it is simply a Red Crossbill!

Red Crossbills belong to the Order Passeriformes (songbirds) and the Family Fringillidae which consists of mostly small, seed-eating birds. Red Crossbills are treasures to Vancouver Island and are often found in flocks looking for pines and other conifers (Sibley Birds West). The remarkable crossed bill allows these birds to access heavily-protected seeds that are bound by the tough scales on conifer cones. This specialized feeding adaptation has lead to Crossbills occupying niches many other species cannot.

Description and Identification

The Red Crossbill is a type of finch that is described to have a large head, stocky body, and of course a uniquely crossed bill (eBird). These birds are classified as medium-sized songbirds that are larger than a warbler but smaller than a Red-winged Blackbird, however there is a lot of variation in size (All About Birds). Like many other finch species, Red Crossbills are sexually dimorphic. Sexual dimorphism means that males and females have different plumage colours or patterns, making the sexing of these birds relatively easy. Red Crossbill males are either dull red or orange, whereas the females are more of an olive-dull yellow colour. Both sexes have brownish wings and juveniles of this species are streaked.

A: Adult Male

B: Adult Female

C: Juvenile

While hiking through the forest, you may hear the sweet trill of a male Red Crossbill singing up in the treetops of conifers. Mostly males perform the warbling song but in rare cases female Crossbills will also sing (All About Birds). Audio 1 contains the Red Crossbill song that consists of several notes that sound like the flight call, followed by a loose trill. In Audio 2, the hard kip-kip flight call can be heard. This flight call is different than the song and performed by both males and females to communicate.

Red Crossbills come in many types, named “call types” with small variations in bill size and flight call. Differentiating between call types requires advanced identification skills, as well as analysis of recorded call sounds. For example, an experienced birder may be able to tell which call type the female Red Crossbill in Video 1 is based on the sound of her call and what type of tree she is found in.

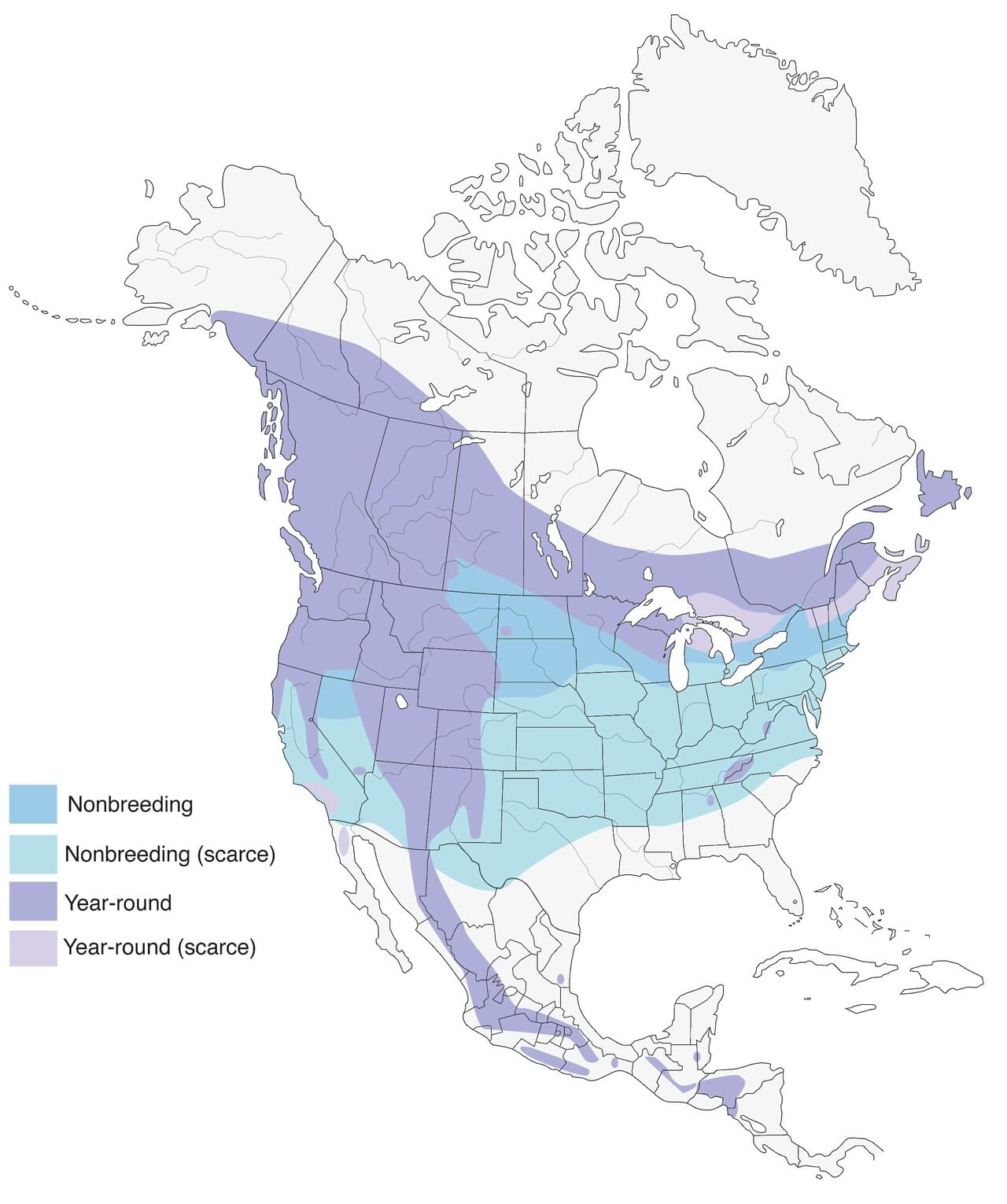

Distribution and Habitat

Red Crossbills mostly reside in coniferous forests and groves and favour trees such as spruce, pine, Douglas-fir and hemlock (All About Birds). British Columbia has an abundance of these coniferous forests and many are found on Vancouver Island. It is no surprise that you can find these conifer-specialists hanging out in our mature forests year-round. However, if you see a Red Crossbill in your neighbourhood don’t expect it to stay long. These birds are nomadic which means they track environmental conditions to go wherever is favourable.

Red Crossbill survival depends on their ability to adapt to the environments they reside in. Variability of Crossbills is found among different coniferous forests, or even within the same forest depending on which type of tree the bird specializes in. One of these variations can be bill-length (how deep the bill can go), which dictates how fast seeds can be extracted from cones. (Siepielski & Benkman, 2005).

Some studies have observed a co-evolution pattern between Red Crossbills and conifers. In regions that do not have many competitors for seeds, larger and thicker cones have evolved (Benkman, 2009). As you can guess, Red Crossbills that have larger bills are favoured to feed on these larger, deep- seeded cones. Having regions of conifer-Red Crossbill co-evolution can further increase the diversification of Crossbill types in geographical zone.

Behaviour

Unlike many birds, Red Crossbills do not necessarily breed during the typical spring breeding season. Instead, these unique birds take advantage of whenever breeding conditions are favourable and can breed any month of the year! Like most organisms getting ready to bring new life into the world, Red Crossbills have requirements that must be met in order to breed. One of the major influences of when Crossbills mate is cone production (Dixon & Haffield, 2013). Although they can nest anytime, most Red Crossbills in North America breed from late summer to early fall and/or from late winter to early spring when there are copious amounts of cones. If food availability is exceptionally abundant, monogamous breeding pairs may raise two broods in a single season (All About Birds).

Red Crossbills build their nests on the end of conifer branches and they can be up to 40 feet off the ground. These nests are built with many materials, ranging from twigs and bark to feathers and fur and normally house 3-4 eggs (What Bird). In order to make the magic happen, male courtship behaviour in Red Crossbills consists of a flight song display and in some cases, they may feed the female they are trying to woo (Audubon). Female Red Crossbills will not settle for any sub-par mate, they will only choose a male with the best song who can provide for them. Females invest much of their energy into reproduction, so it is only fair they have high standards!

Since Red Crossbills commonly travel in flocks, communication is key for success. What can be called “nervous energy”, is the Crossbills constantly calling and moving from one tree to the next. These calls seem to possibly be a communication mechanism for seed size, accessibility, or other factors (All About Birds). Red Crossbills are team players, if they find a gold mine of seeds they want everyone in the group to have their fair share.

Conservation Status

Although it may sometimes be difficult to see Red Crossbills feeding way up in the treetops, there is a significant population in most locations they are found. Since 1970, Red Crossbill populations have declined by an estimated 12% (Partners in Flight). Although this may seem like a large reduction, Red Crossbills still qualify as having an overall “low concern” conservation status (State of The Birds). The criteria State of the Birds used for assigning this species a conservation level was looking at looking at factors leading to vulnerability, such as population size, distribution, threats and population trends. The estimated global breeding population of Red Crossbills is 26 million and the estimated United States/Canada breeding population is 7.8 million (All About Birds).

The introduction of species to a habitat housing Red Crossbills may create competition that puts pressure on the bird’s population. One example being the introduction of red squirrels to Newfoundland, which has led to population declines in a subspecies of Red Crossbills (Hynes & Miller, 2014). The diet of red squirrels mostly consists of the seeds of coniferous trees (Trees for Life), which results in squirrels and Red Crossbills having to compete for resources. Red squirrels are also found to be nest predators and decrease the chances of Red Crossbill reproductive success. The Newfoundland Red Crossbill Project estimates there are only 500-1500 individuals of the Red Crossbill subspecies remaining in the entire province of Newfoundland. This subspecies is morphologically different than Red Crossbills found throughout North America, and is thought to only be found in Newfoundland. Unless serious conservation efforts are made, competition as well as habitat loss and deforestation may drive this subspecies to extinction.

Part II: How Did Call Types Evolve?

Over decades of observing Red Crossbills, ornithologists have found that there are slight intra-species differences between features such as bill length and variations in flight call. These very subtle differences have proven to be enough to result in Crossbills breeding almost exclusively with individuals that have the same variations as them, thus creating different “call types” (Sibley Birds West). In order to figure out how separate call types arose, there is speculation of different evolutionary mechanisms.

To identify why there may be as many as a dozen different call types in one geographical area, Martin et al., 2020 explored two hypotheses. The first hypothesis claims that Red Crossbills evolved call types with variation in bill morphology in order to specialize in a “key conifer” in which it feeds on. The second hypothesis Martin et al., 2020 investigated was that call types are geographically separate and spend most of their time in “core breeding areas” that have high seed productivity.

After 8 years of recording Red Crossbill data, Martin et al., 2020 used methods for observing if there were the same number of call types in an area as there were conifers, localizing core breeding areas, and identifying the production of conifer seeds in a core breeding area. This study found that the second hypothesis, geographical areas, can better predict the occurrence of Red Crossbill call types. Martin et al., 2020 found that some areas had more call types than conifers present, ruling out the hypothesis that each call type specializes in their own conifer. Another observation that invalidates this first hypothesis, is that Red Crossbill call types were found to feed on different species of conifers depending on season or location.

While the study conducted by Martin et al., 2020 observed Red Crossbills in Europe, similar results have been found between call types in North America. Red Crossbills were found to feed on seeds that were more readily available rather than a specific species of conifer (Kelsey, 2008). In addition, Kelsey, 2008 stated there was a tendency for call types to return to their core ranges geographically separated from other call types. This isolation may be an explanation for their adaptive radiation and supports the second hypothesis proposed by Martin et al., 2020.

Call types of Red Crossbills may spend long periods of time geographically isolated from each other to find available food suited for their bill morphology. If the hypothesis of geographic isolation remains supported over generations, we may find these adaptations in call types leading towards a speciation event.

References

All About Birds. Accessed Oct. 30, 2020. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

Audubon. Accessed Nov. 2, 2020. https://www.audubon.org

eBird. Accessed Oct. 30, 2020. https://ebird.org/species/redcro

Newfoundland Red Crossbill Project. Accessed Nov. 5, 2020. http://redcrossbillsightings.weebly.com

Partners in Flight. Accessed Nov. 3, 2020. https://partnersinflight.org

Sibley, D. A. (2016). Sibley Birds West: Field guide to birds of western North America (Second ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Siepielski, A.M. and Benkman, C.W. (2005). A role for habitat area in the geographic mosaic of coevolution between red crossbills and lodgepole pine. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 18: 1042-1049.

State of the Birds. Accessed Nov. 3, 2020. https://www.stateofthebirds.org

Trees for Life. Accessed Nov. 3, 2020. https://treesforlife.org

What Bird. Accessed Nov. 2, 2020. https://identify.whatbird.com

This is so informative and well written! I was wondering, is there a bird call that is similar to the Red Crossbill? Another bird it could be confused with?

Hi Baneesha,

Thanks for reading! Bird calls can be hard to identify especially when there is a lot of chatter. One species that we have here locally that is pretty similar to the call of Red Crossbills is the American Goldfinch flight call. While their songs are quite different, the flight call has a similar chirping noise to the Red Crossbill. Although it takes practice, calls between these two species can be identified by listening to the pitch as well as pace of the call. American Goldfinch have a call that is typically faster and has 4-5 notes to it, whereas Red Crossbill calls are a bit slower based and tend to have only 2-3 “kip” notes.

Hope this helps!

Hi Keely,

A very interesting and well written read! I learned a lot and will look and listen for these unique birds. I really liked that the females had some olive green coloring, instead of the males having all the pretty coloring like in most bird species.

I’m glad you enjoyed Darcy! I agree it is nice that the males don’t get all the glory and the females are just as beautiful. If you see or hear a Red Crossbill let me know I would love to hear about it.

Super well done, I loved reading it!

Question about that 12% decline in the population, is that overall in Canada, or across all of North America?

Hi Erika,

Thanks for reading, glad you enjoyed. Looking back on the source where I got the 12% population decline, I gather they are talking about the worldwide population of Red Crossbills. They later go on to talk about specific population numbers from North America but don’t mention how much the populations here have declined.

Hi Keely papa and I always thought the female was the yellowish bird. Did’nt realize there was a red male. Good info ..Keep up the good work.We will be on the watch for other birds.

Hi Nana and Papa,

Now you know who’s who! I’ll be looking forward to talk about these awesome birds with you and maybe even see some together.

Hi keely! i am extremely impressed with all the layers of information! so much to know about this special bird. I can see why you chose it! unique just as you. Wonderful job keep up the amazing work!

Hi Colby,

Thanks so much for reading! Now you can see why I am developing a real love for birds, especially unique ones like these.

Hi Keely,

I love these birds so much, at first I thought I was imagining things when I saw their bill for the first time. Do gray squirrels also compete with the red crossbills, or do they have a different food source. If they do compete, is it to the same level as the red squirrels or would it be more since the grays are so much larger and require more food.

Thanks for sharing!,

Eden

Hi Eden,

I looked into the diet of gray squirrels and found that it is different from Red Crossbills. The squirrels have a large variety in their diet, from eating bark and nuts to wild berries and even fungi. While there may be some competition for conifer seeds, if Red Crossbills are abundant in the area gray squirrels can feed on other resources. As far the literature shows, Red Squirrels are the main competitors for food with Red Crossbills, and it is only the population in Newfoundland that is critically endangered.

Thanks for reading!

Keely

Hi Keely,

Great blog:) I desperately want to catch/band one so I can see that bill up close!!! Call types are really cool! I take it that call types are not the same as subspecies? Do you know if there is interbreeding between birds of different call types?

Thanks for sharing your love of RECR!!

Cheers,

Sam

Hi Sam,

Thanks for reading! I agree, banding a crossbill would be unreal and being able to see that amazing bill… wow. And call types are not classified as subspecies, the only subspecies that I came across was the endangered population on Newfoundland. Red Crossbills prefer to breed within their call types, but it is not unheard of for there to be interbreeding between call types. I believe if RECR bred exclusively within their call types, this could lead to the evolution of more subspecies.

Cheers,

Keely

Hey Keely,

Super cool blog! I have yet to get a good look at a crossbill in my bins, but I look forward to that day! Do you know if Red Crossbills will flock with other species? Similar to the way other species like chickadees and nuthatches go about foraging. Or do they kind of stick to a “member’s only” kind of vibe and only flock as a singular species.

Cheers,

Braemon

Hi Braemon,

Great question! From the literature, it seems as though Red Crossbills flock exclusively with their own. I found a paper that mentioned how even Red Crossbills and White-winged Crossbills do not usually form mixed flocks. This could be due to their extremely specialized mode of feeding and how each call type specializes in a certain type of cone, not needing other species to alert them to food sources they don’t necessarily need to eat. Another possible explanation could be that Red Crossbills are almost always found in flocks, and therefore do not need to join in a mixed flock to have more protection or warning against predators.

Here’s the link to the article I mentioned:(http://www.jeaniron.ca/2011/WinterFinches.pdf#:~:text=The%20two%20species%20normally%20do%20not%20form%20mixed,opening%20the%20small%20cones%20of%20spruce%20and%20Tamarack)

Thanks for reading,

Keely