What do you get if you cross an orange with a songbird? A tanager-ine! These colourful birds light up forests all over western North America. Whether you recognized the vivid plumage or the robin-like song, western tanagers are a fascinating and beautiful highlight of birding in BC!

Identification and Classification:

Birding for western tanagers can be difficult because of its expert camouflage. Before we get too far into the details I have designed an exercise to help train your eyes so when the time comes you can pick them out from their surroundings:

SPOT THE DIFFERENCES

If you’ve heard of the western tanager before you’re probably most familiar with the vibrant warm colours of the males. While male western tanagers may look like they’re incredibly embarrassed, the bright red “blushing” of their face is actually caused by a unique pigment called “rhodoxanthin” which the tanagers obtain from insects in their diet (All About Birds). During the breeding season this red plumage can cover the entire head, while the rest of the year it is mostly confined to around the beak (Sibley, 2016). Female western tanagers lack the distinctive red plumage and have much more subdued colouration overall.

Other identifying features of male western tanagers are the black wings, back and tail, with yellow shoulder feathers (median coverts) and a white wingbar (tips of the greater secondary coverts). Females are much less colourful, with a pale yellow head and rump, gray back and breast, and dark gray wings with two white wingbars.

Western tanagers belong to the genus Piranga which includes several other red-ish tanagers such as the flame-coloured tanager, red-headed tanager, and hepatic tanager.

While historically tanagers have belonged to the family Thraupidae, molecular evidence has found that many tanager species, including the western tanager, actually belong in the family Cardinalidae, alongside cardinals, grosbeaks, and buntings (Burns et al, 2014).

Distribution:

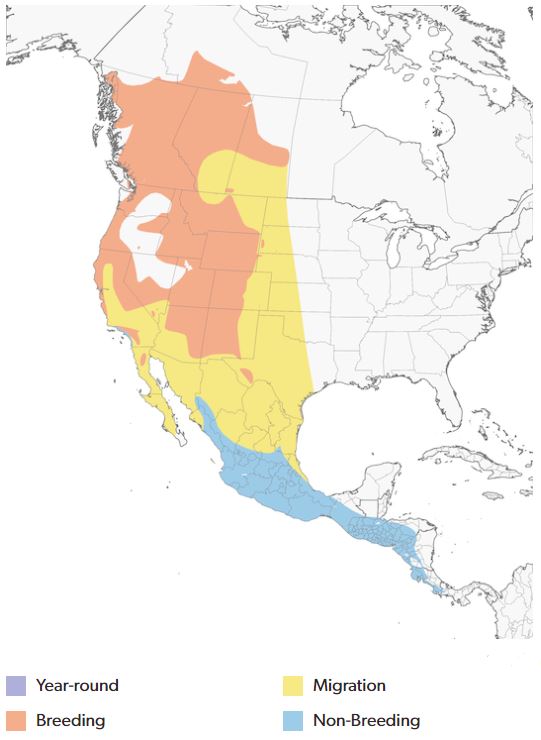

As their name suggests, western tanagers can be found in Western North America, with a breeding range that extends from the Pacific Coast to the eastern side of Saskatchewan. Western tanagers also have the most northerly distribution of any tanager, as they can be found establishing breeding communities up in the Northwest Territories. In general, western tanagers prefer wooded areas with open canopies, such as wetlands, forest edges, and burn sites. In urban settings these conditions manifest in parks and forested gardens (All About Birds).

Figure 1. Distribution of western tanager native ranges. Credit: Birds of the World

Western tanagers overwinter in Mexico before setting off for their northern breeding grounds in spring. In the fall these birds return south to their wintering grounds (State of the Birds). Migration occurs at night and generally in groups of 1-30 individuals (All About Birds; Hudon, 1999). All western tanagers migrate each year, so they do not have any regions of year round habitat (All About Birds).

Figure 2. Heat map of the relative weekly abundance of western tanagers. Brighter colours indicate higher relative abundance. Credit: State of the Birds

Diet and Foraging:

While in their breeding grounds, western tanagers primarily feed on large insects such as beetles, grasshoppers, and dragonflies (All About Birds). Insectivorous birds generally have two categories of hunting methods:

Gleaning

Hawking

For western tanagers, the region they inhabit significantly impacts the way they hunt. Western tanagers hunting in California split their time roughly evenly between gleaning and hawking, however those in British Columbia almost exclusively hunted by gleaning, with hawking only occurring in 3.7% of the observations (Morgan et al, 1991).

During their fall migration and while overwintering in Mexico, western tanagers’ diet mostly consists of fruits and berries (All About Birds).

Behaviour:

When looking for a female, male western tanagers establish territories and guard them by singing (All About Birds).

Female western tanagers build cup-shaped nests out of woven branches, roots, and grasses and lined with soft mosses, feathers, and sometimes even animal hair within which they lay clutches of 3-5 bluish eggs (All About Birds). Incubation generally takes less than two weeks.

How Are They Doing?

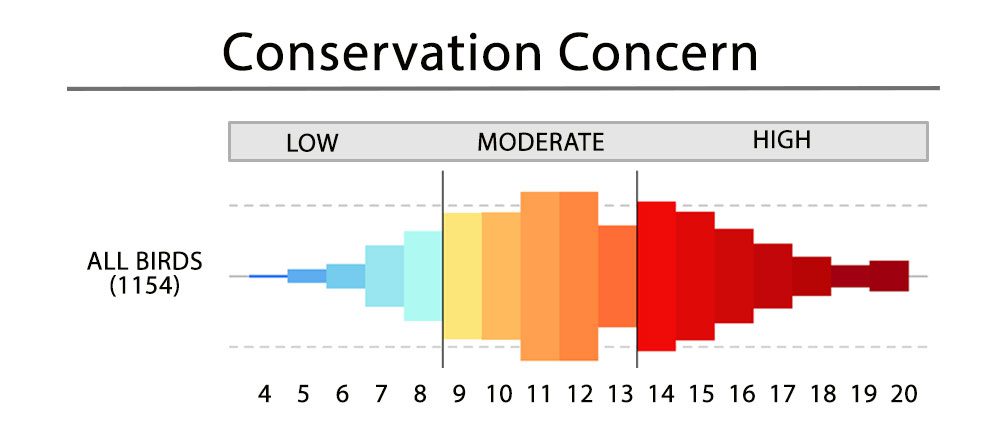

Western tanagers are categorized as least-concern by the IUCN (Government of Canada) and are rated a 9 out of 20 on the Continental Concern Score, indicating a position on the low side of moderate conservation concern (All About Birds).

There are estimated to be approximately 15 million western tanagers breeding in the wild (Partners in Flight).

Western tanagers are preyed upon by many larger birds such as red-tailed hawks, American goshawks, and Cooper’s hawks (Hudon, 1999). In addition, western tanager nests are often preyed upon by several species of owls and jays.

These nests are also plagued by rampant brood parasitism (laying eggs in another nest and making them raise the hatchlings) by brown-headed cowbirds.

When it comes to anthropogenic threats, as with many native bird species, domestic cats pose a considerable threat to western tanager populations (Hudon, 1999).

On a positive note, western tanagers are more resistant to the effects of habitat fragmentation than some other birds because they prefer to live in forest edges and are adapted to capitalize on natural disturbance sites like burns (All About Birds).

Tanagers of Science!

Western tanagers have been featured in several recent research projects. One such study examined the relationship between avian nesting behaviour and forest disturbance caused by the recent mountain pine beetle epidemic (Mosher et al, 2019). This study found that western tanagers (alongside Cassin’s vireo and Clark’s nutcracker) were more likely to inhabit ponderosa pine stands after their infestation with mountain pine beetles than before. If we think back to the nesting habits of western tanagers, this finding makes sense: western tanagers prefer open canopies and disturbed sites. Therefore, the increased tree mortality caused by the beetle epidemic would have opened up the canopy and made the stands more “attractive” to the nesting tanagers.

Another study compared how the “urban tolerance” (e.g. willingness to use urban areas for nesting, foraging, etc.) of birds changed over the course of the year. This study found that birds in general tend to use urban areas less during the breeding season (Callaghan et al, 2021). Another component of this finding was that migratory birds, including western tanagers, have a much greater aversion to using urban areas during the breeding season than resident birds. These results are important for helping to understand the effect of increasing urbanization in North America on native bird species.

Western tanagers were also featured in a study looking at the habitat preferences of migrating birds. This study specifically examined northward migrations through central New Mexico, a route that many western tanagers take each spring (Avery & Keller, 2018). One key finding illustrated in this paper was that while migrating, these birds prefer to forage and rest in sites similar to their ideal breeding sites. This suggests that breeding habitat specificity impacts the birds’ behaviour even outside of the breeding season.

Lastly, a bizarre finding from one of these studies concerns the plant species Boerhavia torreyana or “Torrey’s spiderling”. The stems of these medium sized flowering herbs feature sticky rings to trap insects and deter herbivory (Wilder, 2019). What’s surprising is that these plants have been found to frequently trap–and occasionally kill–small birds that migrate south in the fall, including the western tanager. Because the insects trapped on the adhesive rings are often struggling to free themselves, it is likely that insectivorous birds could be inadvertently “lured” in and then become caught in a tangle of sticky stems.

Thank you for taking the time to learn about the magnificent western tanager! If you have any comments or questions, please do not hesitate to leave your thoughts in the comment section just past the references!

References

Avery, J. D., & Keller, G. S. (2018). Spring migration patterns of birds in montane habitats of the southwestern United States. The Southwestern Naturalist, 63(1), 17-25. https://doi.org/10.1894/0038-4909-63.1.17

Burns, K. J., Shultz, A. J., Title, P. O., Mason, N. A., Barker, F. K., Klicka, J., Lanyon, S. M., & Lovette, I. J. (2014). Phylogenetics and diversification of tanagers (Passeriformes: Thraupidae), the largest radiation of Neotropical songbirds. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 75, 41-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.02.006.

Callaghan, C. T., Cornwell, W. K., Poore, A. G. B., Benedetti, Y., & Morelli, F. (2021). Urban tolerance of birds changes throughout the full annual cycle. Journal of Biogeography, 48(6), 1503-1517. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14093

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Western tanager. All about birds. Retrieved September 22, 2024 from https://allaboutbirds.org/guide/Western_Tanager/lifehistory

Government of Canada. (2015, August 19). Western tanager (Piranga ludoviciana). Migratory Birds. Retrieved September 22, 2024 from https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/oiseau-bird-eng.aspx?sY=2019&sL=e&sM=c&sB=WETA

Hudon, J. (1999). Western tanager—Piranga ludoviciana. In A. Poole & F. Gill (Eds.), The birds of North America. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Morgan, K. H., Savard, J-P. L., & Wetmore, S. P. (1991). Foraging behaviour of forest birds of the dry interior Douglas-fir, ponderosa pine forests of British Columbia. Canadian Wildlife Service, Pacific and Yukon Region. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/eccc/cw69-5/CW69-5-149-eng.pdf

Mosher, B. A., Saab, V. A., Lerch, M. D., Ellis, M. M., & Rotella, J. J. (2019). Forest birds exhibit variable changes in occurrence during a mountain pine beetle epidemic. Ecosphere, 10(12). https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2935

North American Bird Conservation Initiative. (n.d). Methods. State of North America’s birds 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2024 from https://www.stateofthebirds.org/2016/overview/methods/

North American Bird Conservation Initiative. (n.d). Western Tanager. State of North America’s birds 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2024 from https://www.stateofthebirds.org/2016/resources/species-abundance-maps/western-tanager/

Partners in Flight. (n.d.). Avian conservation assessment database scores [Data set]. Bird Conservancy of the Rockies. https://pif.birdconservancy.org/ACAD/Database.aspx

Sibley, D. A. (2016). The Sibley field guide to birds of western North America. (2nd ed.). Alfred A. Knopf.

Wilder, J. A. (2019). A true “migrant trap”: Boerhavia (Nyctaginaceae) entanglement as a recurring cause of avian entrapment and mortality. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 131(3), 658-663. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27014186

What a great study. I found it very interesting to listen to the variations of this bird’s song in this article. Additionally, the many lovely photographs of this bird kept the article visually appealing to read.Finally, thank you for including the many facets of this unique bird’s life.

I’m glad you enjoyed it! I really appreciated the photo of the female western tanager eating a raspberry (Fig. 5).

Excellent well-written review integrating great photos and super cool ecology and behaviours of a fascinating bird. Amazing to learn how the males get their vibrant colours and that the species is particularly susceptible to brood parasitism! Great job Isaac!

Thank you! I thought the rhodoxanthin pigment was quite interesting as well. It would be interesting to see if there are any specific traits that make them more susceptible to the brown-headed cowbird’s brood parasitism.

Really interesting write up! I’ll be keeping my eyes open for these guys! I wonder if there is a difference in diet between the males and females to achieve a higher concentration of rhodoxanthin for the bright red plumage or if the pigment is just expressed more in males.. either way, super cool!

That’s a very interesting point! I’d also be curious to see if the red colour can be artificially induced by feeding Western Tanagers insects in their winter grounds.

Hi Isaac, Wonderful blog post. I was just wondering, based on their behaviour and feeding habits if you had any advice I could give to my grandma who is hoping to attract Western Tanagers to her backyard feeder. What sort of food should she put out and would the tanagers be interested in human made nest boxes?

Thank you! Western Tanagers mostly feed on insects while they’re up here (unless your grandma lives in Mexico), but that might be somewhat difficult to arrange with typical bird feeders. I would recommend a mix of fresh and dried fruits, such as oranges and raspberries, and maybe a few dried mealworms. You should definitely avoid mangos though because you don’t want to encourage cannibalism.

How could cats possibly avoid eating them when they look identical to sweet juicy mangoes?!

Great post Isaac! I enjoyed reading about the Western Tanager and also looking at the fantastic photos.

My question is, do Western Tanagers pair-bond and/or display monogamous mating behaviours, or do they have multiple partners in a season?

Thanks so much for your awesome post.

Isabella

Thanks! Western Tanagers do form seasonal pair bonds, and the male will even feed the female while she builds the nest. I haven’t been able to find any confirmed reports of extra pair mating, however one account stated that males would follow females around very closely around the beginning of the breeding season, which could indicate guarding behaviour to prevent extra pair copulations.