Introduction:

The Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris) is a common, yet distinctive, duck found across North America. It’s prominent black and white plumage, brightly contrasted eye colour, and unique head shape which are best used in its identification begs the question: where is the ring around its neck? Interestingly enough, the Ring-necked Duck received this name during the 19th century by biologists examining dead specimens, where the faint light-coloured band around the neck of the carcass peaked their attention (AllAboutBirds.org). Despite its misleading name, the Ring-necked Duck is frequently and easily identified by bird enthusiasts and biologists along its migration routes and nesting grounds. In fact, the Ring-necked Duck’s abundance in the U.S. state of Minnesota and surrounding Great Lakes area has been of particular interest for wildlife management studies… Keep reading to find out more!

Description & Identification:

The Ring-necked Duck belongs to the order of birds called Anseriformes and are a member of the Anatidae family which includes various ducks, swans, and geese. More specifically, Aythya collaris is classified within the Aythyini tribe, a group of about 17 different species of ducks who specialize in diving (Livezey, 1996). Despite belonging to a relatively large group of ducks, the Ring-necked Duck’s physical appearance truly sets it apart.

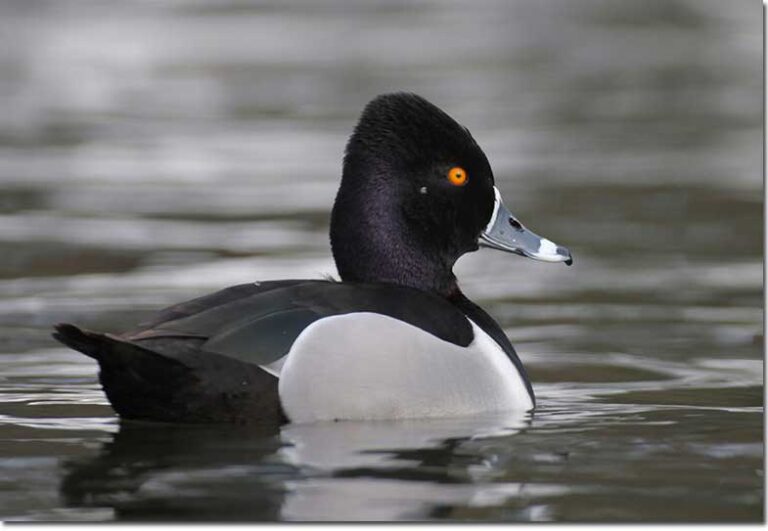

As mentioned, when trying to identify the Ring-necked Duck, don’t be fooled into believing the neck is its most prominent feature. Arguably, the best way to identify a Ring-necked Duck is by its tall head, which has a distinct sharp peak on the rear of its head, also known as its “crown” (Sibley, 2016) (Figure 1).

Like many waterfowl, male Ring-necked Ducks sport the more recognizable livery, with unique black and white plumage while females are clad in more subdued brown tones for camouflage rather than flare (U.S. Fish & Wildlife service). However, both sexes share characteristic traits in the colour of their bills with both males and females having grey bills with black tips and clearly marked white bands across them (Figures 2 & 3) (All About Birds). This distinctive bill pattern has led recognizable organizations like the American Ornithological Society to consider renaming the bird to the “Ring-billed Duck” due to it being such a notable feature (American Ornithological Society).

Another distinguishing trait that sets the Ring-necked Duck apart from other ducks is actually a structural feature that it lacks. The Ring-necked Duck lacks a speculum, which is the bright iridescent patch of feathers seen on some duck’s wings which are often admired by observers (Ducks.org). This absent quality is missing among the ducks known as “pochard” ducks, the technical term for a group of duck species who specialize in diving for food. It can serve as a quick, preliminary way of differentiating Ring-necked Ducks from species such as Mallards or Wood Ducks (Figure 4).

Behaviour:

Ducks are often divided into one of two groups determined by their feeding/foraging behaviour as either “dabbling ducks” or “diving ducks“. Dabbling ducks, also known as “puddle ducks” are those who spend most of their time in shallow water as the name implies. Instead of diving, this group of rather buoyant ducks dip their heads underwater to snatch up food such as aquatic plants and insects below the waters surface (Ducks.org) (Figure 5).

However, the Ring-necked Duck is an expert diving duck, preferring to forage aquatic plants and insects from deeper bodies of water, often several feet deep (Audubon.org). This diving behaviour leads to a trade-off, sacrificing the ability to walk efficiently on land due to its rear-positioned legs which work more effectively as underwater propellers than land-based waddlers.

Additionally, diving ducks such as the Ring-necked Duck, lack the ability to take off vertically from the water’s surface (Audubon.org). This is a result of their specialized adaptation for diving, which subsequently results in a relatively smaller wing size than the dabbling ducks for better underwater maneuverability at the cost of reduced lift (Ducks.org). Consequentially, like other diving ducks, Ring-necked Ducks require a running take-off across the waters surface to generate the required speed necessary for flight.

Distribution & Habitat:

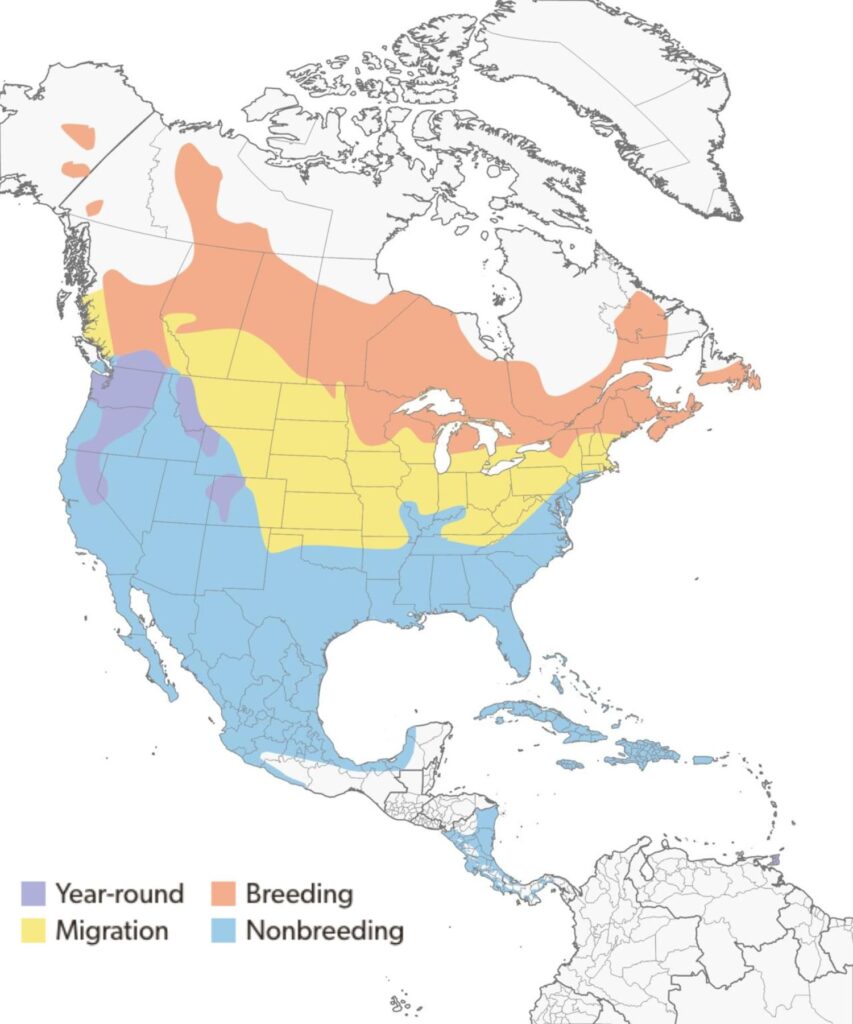

The Ring-necked Duck is rather ubiquitous across North America and parts of Central America, inhabiting various bodies of freshwater (Figure 6) (AllAboutBirds.org). In general, the Ring-necked Duck is often found in lakes, ponds, and bays but can also be found in flooded agricultural fields or other shallow wetlands where diving is not necessary. Most commonly, nesting of Ring-necked Ducks occur in Northern wetlands and bogs (Hohman, 1986). These shallower bodies of water often provide ideal hiding spots for females to nest and care for their young to avoid predators rather than the safety of the open water preferred by many other diving duck species (Audubon.org).

Conservation Status:

The Ring-necked Duck is an abundant species of duck with little concerns for conservation or stewardship needs. Fortunately, the population of Ring-necked Duck in Canada has steadily increased since the 1970’s (Canada.ca).

This species of duck is also economically important in the game industry and is a popular choice for hunting across the U.S. and Canada due to this abundance (Mezebish, 2021). The Ring-necked Duck even ranks among the top five most hunted duck species in Canada (Canada.ca). Their adaptability to various habitats and wide distribution also contributes greatly to their success in maintaining a healthy population across North America (Animaldiversity.org).

Recent Research:

The Ring-necked Duck is a species that gathers in the hundreds of thousands during Fall migrations and breeds in notably large populations within the Great Lakes region and in states such as Minnesota, where extensive surveys have been conducted on their numbers (MinnesotaBreedingBirdAtlas). A recent paper published in 2018 discussed a study which investigated the impact of human activity and development in terms of Ring-necked Duck nest and brood survival with surprising results! This study concluded that both Ring-necked Duck nests and chicks hatched from those nests closer to roads had a better survival rate when compared to those further away from roads (Roy, 2018). It also found that nests and corresponding broods near paved roads with higher vehicle traffic had better survival rates compared to those nests near gravel roads, with presumably less human activity. The author of this study speculated that this could be caused by the negative impacts these roads have on predators of the Ring-necked Duck including racoons and skunks such as impacts with vehicles, consequentially increasing the overall success of Ring-necked Duck populations (Figure 7).

It is important to acknowledge that while these findings indicate some seemingly positive effects of our environmental footprint, which may contribute to explaining the resilience of Ring-necked Duck populations, the overall success of a species relies on various life-history stages beyond just nesting and brood-rearing. Other studies have concluded population decline in habitats such as in forested habitats where seasonal climatic shifts are observed to be intensifying with negative consequences for Ring-necked Duck populations (Roy et al, 2019).

Conclusion:

In summary, the Ring-necked Duck is both a widespread and unique waterfowl species. An expert diver, with special adaptations for survival across freshwater ponds, lakes, and marshes across North America whose presence continues to be welcomed by bird-watchers and hunters alike. The Ring-necked Duck is better known for it’s striking plumage, unapologetically bold cranium, and sizeable migrational flocks than the subtle trait for which it is named.

References:

American Ornithological Society. (n.d.). AOS English Common Names Pilot Project. Retrieved September 30, 2024 from https://americanornithology.org/about/english-bird-names-project/english-bird-names-committee-recommendations/

Anderson, M. (2006). The Big Four – Diving Ducks. Ducks Unlimited. Retrieved September 30, 2024 from https://www.ducks.org/conservation/waterfowl-research-science/the-big-four-diving-ducks

Caitlin, M. (n.d.). Let’s hear it for the ladies!. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved September 27, 2024 from https://www.fws.gov/story/lets-hear-it-ladies

CamoTrading. (2020). The Upside Down Life of Dabbling Ducks. Retrieved September 30, 2024 from https://www.camotrading.com/resources/the-upside-down-life-of-dabbling-ducks/

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Ring-necked Duck. All about birds. Retrieved September 28, 2024 from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ring-necked_Duck/overview

Delta Waterfowl. (n.d.). Top Duck-Craving Predators. Retrieved September 30, 2024 from https://deltawaterfowl.org/top-duck-craving-predators/

Hohman, W. L. (1986) Changes in Body Weight and Body Composition of Breeding Ring-necked Ducks (Aythya Collaris), The Auk, 103(1), 181-188, https://academic.oup.com/auk/article/103/1/181/5191502

Hoosier Bird. (2024, February 27). Ring-necked Duck [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mS8VvNgv6Ik

Kaufman, K. (1996). Ring-necked Duck. Audubon. Retrieved September 27, 2024 from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/ring-necked-duck

Livezey, B. C. (1996). A phylogenetic analysis of modern pochards (Anatidae: Aythyini). The Auk, 113(1), 74–93. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/auk/vol113/iss1/8/

Mezebish, T. D., Chandler, R. B., Olsen, G. H., Goodman, M., Rohwer, F. C., Meng, N. J., & McConnell, M. D. (2021). Wetland selection by female ring-necked ducks (Aythya collaris) in the southern Atlantic Flyway. Wetlands, 41(6). https://ace-eco.org/vol17/iss2/art5/

Migratory Birds. (2015). Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris). Canada.ca. Retrieved September 30, 2024 from https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/oiseau-bird-eng.aspx?sY=2014&sL=e&sM=a&sB=RNDU#uBCRSid

Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas. (n.d.). Ring-necked Duck. Retrieved September 29, 2024 from https://mnbirdatlas.org/species/ring-necked-duck/

O’Donnell, P. (2024). Know Your Ducks: 15 Common Minnesota Ducks [ID Guide]. BirdZilla. Retrieved September 30, 2024 from https://www.birdzilla.com/learn/minnesota-ducks/

Patel, S. (2011). Aythya collaris. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved September 30, 2024 from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Aythya_collaris/

Roy, C. L. (2018). Nest and brood survival of Ring-necked Ducks in relation to anthropogenic development and wetland attributes. Avian Conservation and Ecology 13(1):20. https://www.ace-eco.org/vol13/iss1/art20/

Roy, C. L., Berdeen, J. B., & Clark, M. (2019). A demographic model for ring‐necked ducks breeding in Minnesota. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 83(8), 1720–1734. https://wildlife.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jwmg.21756

Sibley, D. (2016). Sibley Birds West: Field Guide to Birds of Western North America (2nd ed.). Alfred A. Knopf.

Whitehead, T. (2018). How reliable is speculum colour for duck identification?. Wildlight Photography. Retrieved September 28, 2024 from https://www.tonywhitehead.com/wildlight/archives/8786

Cool! I’ve never heard the terms dabbling vs diving before, but that’s a neat way to classify them! I sure hope they rename it the ring billed duck. That makes way more sense

Thanks for the comment Kennedy! I agree that a rename to Ring-billed Duck is in order!

What an engaging and informative post! I was especially intrigued by the unexpected way Ring-necked Ducks benefit from human activity along roads and how hunting hasn’t significantly impacted their numbers. It’s reassuring to see examples of nature’s adaptability and resilience to some anthropogenic factors. I think it’s great too that despite this you made it clear in your post that broader conservation concerns shouldn’t be overlooked! Thanks for a fantastic read and I loved the diving Ring-necked Duck drawing!

Thanks for checking out my post Emily! It’s definitely nice to find some optimistic results when discussing our anthropogenic impact on wildlife. And I’m glad you enjoyed my diving RNDU doodle haha

First of all, I LOVE your hilarious drawing of a diving duck, Evan!

I’ve recently seen flocks during my strolls around Cottle Lake (in Linley Valley Park), and it makes sense now that they would be present in a lake that is in the middle of an urban/residential area with the potential advantage of lower predation rates. It would be interesting to further explore their resiliency in rapidly changing climatic conditions.

Also I’m surprised there aren’t more “Ring-necked” species from 19th century scientists trying to name dead birds…lol. “Ring-billed” Duck for the win!

Thanks so much for your feedback Isabel, it made my day! Good tip on where to find this bird too! I haven’t had any luck finding one so far so I’ll have to check out Cottle Lake like you said!

Awesome Post, Evan!

I could watch that video of them diving all day, they are so elegant with it and such good-looking waterfowl. Also, your drawing at the end is truly amazing and that’s exactly how I picture them looking underwater. I saw a flock of them at Buttertubs Marsh last Thursday, you should go check them out! Unfortunately, I didn’t bring my mask and snorkel so I didn’t get to witness them in their little submarines… maybe next time.

I’m so happy to read that their populations are doing great! It’s so interesting that human impacts (roads) are even benefitting them in a way- a nice light amongst a lot of posts linking anthropogenic impacts to that species’ decimation. I appreciate the disclaimer that humans negatively impact them on another scale, but that is unfortunately to be expected.

Thank you for the fun read!!

Thanks for the comment Keya! I’m jealous that you managed to see some Ring-necked Ducks in action. I’m still not entirely convinced they’re real.. But when I do finally see one, I’m going to make quite a scene!

Nice post Evan!

I seem to see these ducks everywhere I look now that I know how to ID them, after reading your blog I understand why! I didnt know they where spread across the whole continent!

It is good to see that anthropogenic activity helps with the hatching success of their eggs. I have read about other species of birds that benefit from nesting close to urban areas, it would be cool to see research that compares the benefits and the costs of human activity to see if it really does help them or if it is just superficial!

Hey Olivier, thanks for checking out my post!

That’s interesting to know that comparable studies have been done on other species with similar results. I’m sure that studies like this fall short of capturing the entire picture. However, it would be interesting to further explore this relationship between the Ring-necked Duck and humans, as it could be possible they have a commensalistic, or even mutualistic, interaction with humans, similar to the relationship between humans and pigeons.