Drumroll please for Birds Canada’s 2024 Avian Ambassador…

The winner is the OLIVE-SIDED FLYCATCHER! (Birds Canada)

IDENTIFICATION

Olive-sided Flycatchers (Contopus cooperi) are classified under class Aves, order Passeriformes, and family Tyrannidae (Government of Canada, 2018). The key to identifying this flycatcher against similar species is the prominent colouring of the breast plumage, seemingly wearing a grey vest with a white undershirt (Sibley, 2016). This identifying feature is present in both males and females (All About Birds); being the best dressed whether it’s an award ceremony or being the best man at your wedding. So why does this bird claim to be “Olive-sided” if the feathers appear as shades of grey? The wing feathers are darker than the vest with olive tones that are only visible when the feathers have been freshly molted or if the lighting is perfect (All About Birds)… A bird that needs the spotlight. White tufts are located on the sides of their rump, although only visible when relaxed (Sibley, 2016), which is rare since they’re usually seen upright, scanning for the next meal.

Olive-sided Flycatchers are stocky and barrel-chested with a relative size between a sparrow and a robin, averaging 19 cm in length and a mass of 34 g (All About Birds). Relative to its small size, its dark grey head is large with a heavy and long bill. The wings are long and pointed, with an average wingspan of 33 cm, and the tail is short relative to the wings, squared off and lightly notched (Sibley, 2016).

What is an Olive-sided Flycatcher’s favourite beverage? “Quick, Three Beers!” So demanding. Their song’s three-note whistle is easily recognizable and can be heard up to 1 km away (Government of Canada, 2018). Their call on the other hand is a low and hard Pep, Pep, Pep (Sibley, 2016).

HABITAT AND DISTRIBUTION

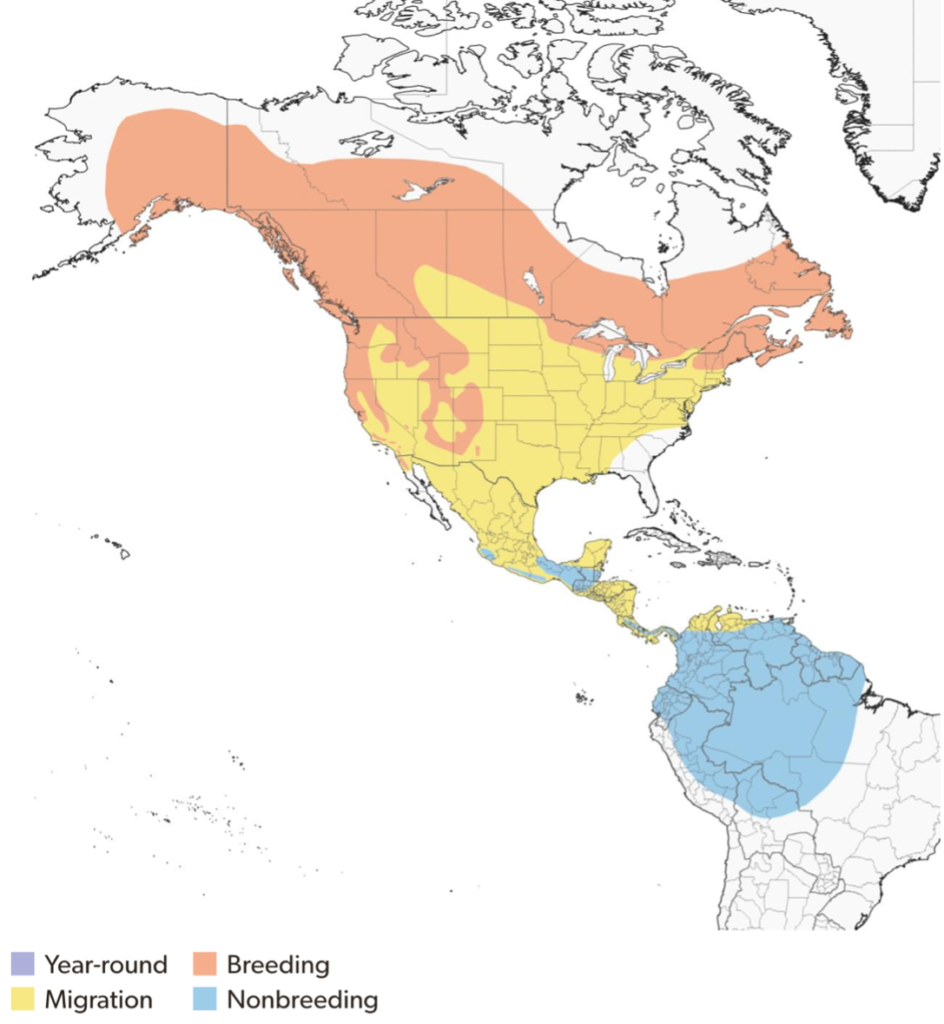

Olive-sided Flycatchers breed mostly in boreal and western coniferous forests, from sea level to the alpines. They nest in openings or edges of forests, including wetlands, partially logged areas, and recently burnt forests. Snags (dead or dying trees with bare limbs) are commonly found in their habitats, supplying the flycatcher with perches for singing, foraging, and guarding their habitat (All About Birds).

During migration, they are found in partially treed forests along waterbodies with perching opportunities. Their migration is long, arriving on breeding grounds in Canada and parts of the United States in late spring, and leaving around August, where some migrate a distance greater than 10,000 km! On their wintering grounds, they use forests with gaps and forest edges, in high and low elevations of Central and South America (All About Birds).

Figure 1. Distribution Map. Credit: All About Birds.

FEEDING

This may be a shocking statement and I hope you believe me, but Olive-sided Flycatchers catch flies! Most of their time is spent perched up high on tree branches and snags, looking for flying insects. When the prey is spotted, they launch off their perch, catch the insect in their bill, and return to their perch to gobble down their meal; this maneuver is called “sallying” (All About Birds). Their bills are so strong that if you listen to an Olive-sided Flycatcher catch an insect from the air, you can hear a loud SNAP once their bill closes (Birds Canada).

Their meals of choice include flies, flying ants, wasps, bees, dragonflies, beetles, moths, and so on. During the non-breeding season, only a few observations of Olive-sided Flycatchers eating berries have been recorded (All About Birds). They love their flying protein- maybe it’s the thrill of the chase!

Photo credit: Dan Streiffert

BREEDING

During the breeding season, the male chases down a female while performing a short display of flight, in hopes that the female will like it and join in. Competing males are chased away and if the female has been won over, the pair will raise their crest feathers, click bills, pump their tails and bodies, and we know what comes next (All About Birds). The bond between the established pair is so strong that they will attempt renesting if their brood has failed, and may nest for consecutive years (Altman, 1997).

The nest is a small, bulky cup made of twigs and roots, lined with grass, fine roots, lichen, and conifer needles. They only have one brood during the breeding season with an average clutch size of 3-4 eggs. (All About Birds). Their nesting territories are quite large, up to 40-45 hectares per pair (Altman, 1997) and they are aggressive defenders of their nests. A pair was seen knocking a red squirrel off a limb of their nest to defend their nestlings, chasing it away to ensure it wouldn’t return to their young (All About Birds). Feisty little birds, I wouldn’t mess with them.

CONSERVATION

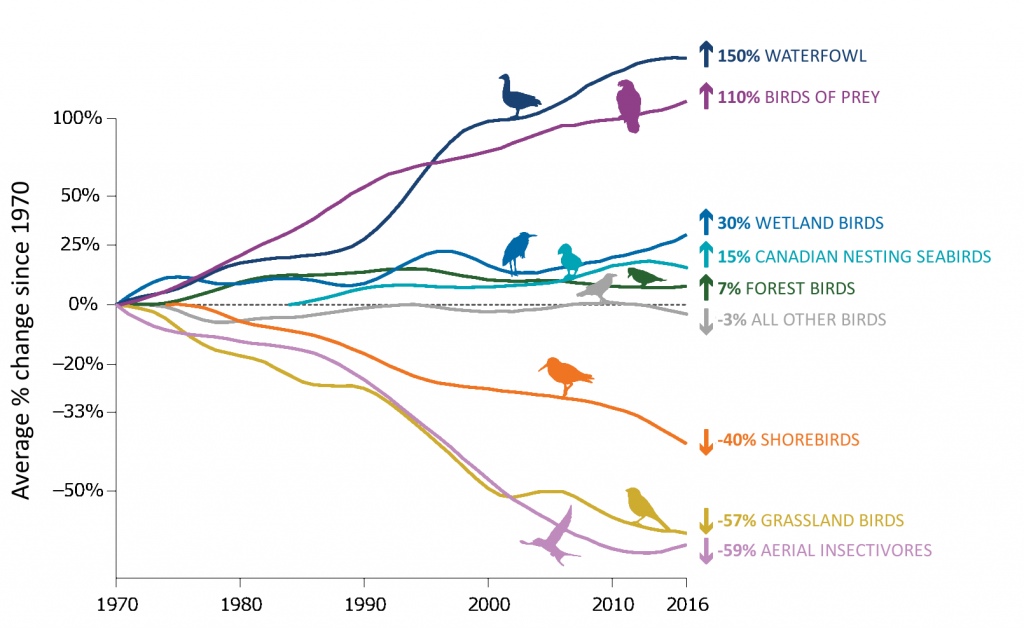

The Olive-sided Flycatcher belongs to the group of aerial insectivores whose population has been declining since the 1970s (nabci).

Canada’s 1994 Migratory Birds Convention Act protects Olive-sided Flycatchers and their nests. Additionally, it is protected under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) where the species has been listed as Special Concern, which has improved since the previous ranking of Threatened (Government of Canada, 2018 and 2023).

In 2016, SARA wrote a recovery strategy for the Olive-sided Flycatchers in Canada, listing the greatest threats to their population and an objective to stop their decline by 2025 (Environment Canada, 2016). The first major threat is a reduction of prey; the availability of insects has been reduced (van der Sluijs, J. P., 2020) due to a decrease in insect-producing habitats, climate change (Robinson et al., 2009), and the use of pesticides (Nocera et al., 2012) and the second major threat is habitat loss, due to fire suppression, deforestation, and land conversion (Environment Canada, 2016).

Organizations are trying to understand the extent of why their populations are declining and help conserve habitat known to be utilized by the Olive-sided Flycatcher. Being the Birds Canada Avian Ambassador of 2024 will hopefully help spread knowledge about the Olive-sided Flycatcher and the issues they are facing (Birds Canada). Nature Conservancy Canada (NCC) has been protecting various properties where Olive-sided Flycatchers have been seen during breeding or migration (NCC). Our neighbours in the states at the University of Vermont suggest that the conservation, restoration, and creation of wetlands could support the declining population of the Olive-sided Flycatcher in the northeastern United States (Dillon, 2021).

RESEARCH

To better understand the declining population of the Olive-sided Flycatcher, habitat models have been created to demonstrate the effect of the forest management policies in the southern Peace River region in British Columbia (Norris et al., 2021). These models included logging, roads, land-use changes, fires, and insect outbreaks, such as the mountain pine beetle (Norris et al., 2021). The results indicated that the extent of suitable Olive-sided Flycatcher habitat would decline for the next 30 years if the existing forest management policies remain the same (Norris et al., 2021). Changes in forestry practices, such as decreasing clearcut sizes and maintaining historical fire regimes could help reduce the dramatic population decline of the Olive-sided Flycatcher (Norris et al., 2021).

It was hypothesized that selectively harvested forests are an “ecological trap” for Olive-sided Flycatchers, emulating the appearance of a naturally occurring burned forest (Robertson and Hutto, 2007). In the study, Olive-sided Flycatchers were more attracted to the harvested forest, potentially due to a greater amount of nest trees and insects, however, nest success was worse in the harvested forest than in the natural habitats, due to a greater amount of predators (Robertson and Hutto, 2007). Recent research about the theory of ecological traps is being conducted by Chu Cho Environmental from Prince George, British Columbia. Below is a video demonstrating their ongoing monitoring efforts to study the Olive-sided Flycatcher’s population and habitat.

Thank you for reading and let’s have a beer (or three) in celebration of the Birds Canada 2024 Avian Ambassador, the Olive-sided Flycatcher! Cheers to the current and future efforts to protect this amazing at-risk species by understanding its critical habitat and ecological demands.

Please leave comments below, I’m looking forward to chatting with you.

REFERENCES

Altman, B. 1997. Olive-sided Flycatcher in western North America. Status review prepared for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Oregon State Office, Portland. 59 pp. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.arlis.org/docs/vol1/FWS/1997/993882846.pdf

Birds Canada. 2024. Introducing Birds Canada’s 2024 Avian Ambassador: The Olive-sided Flycatcher. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.birdscanada.org/introducing-birds-canadas-2024-avian-ambassador-the-olive-sided-flycatcher

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Olive-Sided Flycatcher. All About Birds. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Olive-sided_Flycatcher/lifehistory

Dillon, K. J. 2021. A Model of Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi) Occupancy in the Northeastern United States. UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 426. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/426

Environment Canada. 2016. Recovery Strategy for the Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vii. 52. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/recovery-strategies/olive-sided-flycatcher-2016.html

Government of Canada. 2018. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi) in Canada 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/cosewic-assessments-status-reports/olive-sided-flycatcher-2018.html#toc9

Government of Canada. 2023. Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi). Species at Risk Public Registry. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://species-registry.canada.ca/index-en.html#/species/999-683

NABCI Canada. 2019. The State of Canada’s Birds 2019. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from http://nabci.net/resources/state-of-canadas-birds-2019/

Nocera, J. J., Blais, J. M., Beresford, D. V., Finity, L. K., Grooms C., Kimpe, L. E., Kyser, K., Michelutti, N., Reudink, M. W.,, and Smol, J. P. 2012. Historical pesticide applications coincided with an altered diet of aerially foraging insectivorous Chimney Swifts. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 279(1740). 3114-3120. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0445

Norris, A.R., Frid, L., Debyser, C., De Groot, K. L., Thomas, J., Lee, A., Dohms, K. M., Robinson, A. Easton, W., Martin, K., & Cockle, K. L. 2021. Forecasting the Cumulative Effects of Multiple Stressors in Breeding Habitat for a Steeply Declining Aerial Insectivorous Songbird, the Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi). Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.635872

Robertson, B. A. & Hutto, R. L. 2007. Is Selectively Harvested Forest an Ecological Trap for Olive-sided Flycatchers? The Condor, 109(1,1). 109-121. https://doi.org/10.1093/condor/109.1.109

Robinson, A., Crick, H. Q., Learmonth, J.A., Maclean, I. M., Thomas C. D., Bairlein F., Forchhammer, M. C., Francis, C. M., Gill, J. A., Godley, B. J., Harwood, J., Hays, C. G., Huntley, B., Hutson, A. M., Pierce, G. J., Rehfisch, M. M., Sims, D. W., Santos, M. B., Sparks, T. H., Stroud, D. A., and Visser, M. E. 2009. Travelling Through a Warming World: Climate Change and Migratory Species. Endangered Species Research, 7. 87-89. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00095

Sibley, D.A. 2016. Sibley Birds West: Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Second Edition. Alfred A. Knopf. 274.

van der Sluijs, J. P. 2020. Insect Decline, an Emerging Global Environmental Risk. Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 46. 39-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.08.012

Nature Conservancy Canada. 2024. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.natureconservancy.ca/en/what-we-do/resource-centre/featured-species/birds/olive-sided-flycatcher.html

Really interesting post and species pick Keya! The idea of needing more bugs flying around doesn’t sound particularly appealing to me personally but I guess it’s more about balancing the ecosystem and restoring natural habitats so the right kinds of insects are around in the right places for these birds to feed on. I thought the hypothesis that harvested forests are resulting in an ecological trap for these birds was intriguing and sounds a lot like what is happening with our Vancouver Island marmot species. Definitely lots of opportunity for more research!

Thank you so much for your comment, Evan! Haha yes, an increase in the amount of flying insects isn’t very appetizing to humans, but I agree with calling it a balancing act. Well said. That’s interesting to have related the ecological trap theory to what is happening to the Vancouver Island marmots, I don’t know much about why their population has been declining and will definitely look into it. Let’s save the marmots and the Olive-sided Flycatcher! Cheers!

Thanks for the entertaining read Keya, I really like your writing style!

It’s interesting to see how even selective logging (a better alternative to clear-cutting) can pose a threat to perching birds as “ecological traps”, it’s not just the marmots that are being fooled! Cheers to future research and increasing conservation efforts!

That is so sweet Isabel, thank you for your comment! Yes, selective logging doesn’t solve the issue, even though it is an improvement to forestry practices. Humans will keep finding ways to improve their ways but unfortunately, we always seem to mess with natural occurrences. So cheers to that, let’s try to have a positive effect through research and conserving/ restoring the Olive-Sided Flycatcher’s critical habitat!

Fascinating read Keya. I really enjoyed the description. It is very detailed and very helpful in differentiating the Olive-sided Flycatcher from other similar species. I was wondering, in regards to their feeding habits, do these flycatchers show a preference of certain types of insects over others in anyway, say flies over moths, and if so, is it region dependent? Will a Olive-sided flycatcher on the West Coast have different preferences to an East Coaster?

Thank you for your lovely comment, Grace! That is a great question regarding their feeding habits. From what I found, their diet varies from time of year and location, based on what insects are available. I am not an entomologist, but I think there are differences in the type of insects flying around from one region to the next, especially between their breeding and non-breeding grounds. I think the rule of thumb is as long as the insect flies, the flycatcher will eat it if it is large enough to be worth the sally but small enough to catch. Birds Canada did state that bees are one of their favourite insects, but I’m not sure how they found that out, maybe it was part of the interview questions when they handed over the award. Cheers!!

That is very interesting, Keya. It makes sense that the favoured insect depends on availability. Thank you for replying

Hi Keya! I love your blog,

I really appreciated the humor incorporated in your blog. It helped me engage in the material!

In regard to the breeding season, do males or females make the nest? And you had mentioned breeding pairs may stay together for multiple seasons, is there a limit to how long they generally stay together for?

Great job! Definitely a well written blog!

Eric

Thank you for your comment and kind words, Eric!

Great questions regarding their breeding behaviours. The female is in charge of deciding on the nesting location and building the nest, however, they say that the male does sometimes participate… we love a supportive partner! Upon diving deeper and learning about the different mating systems, Olive-sided Flycatchers are known as being socially monogamous. They were previously believed to be fully monogamous, with only one clutch per pair per year, however, the men seem to be sneaking around a little. I’m sure she doesn’t mind if her man gets around for a little extra-pair mating, it’s nice to have a little time to yourself. There are two cases where pairs have nested in consecutive years but I can’t find the paper where this information came from and I don’t know if that means 2 years or more. Unfortunately, it does not seem to be a life-long relationship.

Cheers!!