Pacific Wrens (Troglodytes pacificus) are minute songbirds known for their remarkably loud and complex song, which echoes throughout the understory of the mature forests in which they live. With thin, narrow beaks, these little round birds search for insects inside crevices and hollows on the forest floor, which has earned them their generic name Troglodytes, from the Ancient Greek word for “cave dweller”.

Description & Identification

Physical and Comparative Description

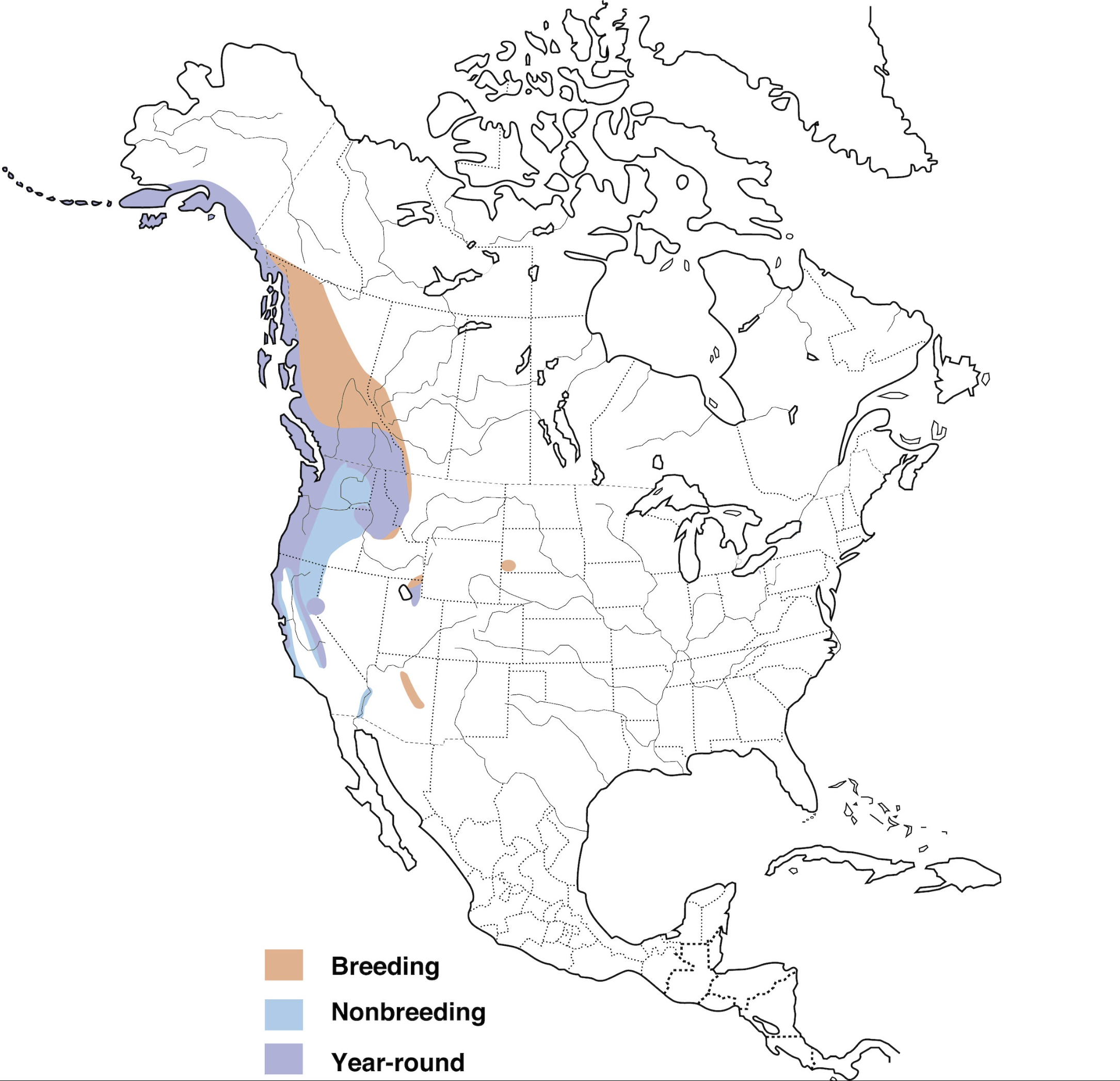

In general, Wrens can be identified by narrow bills, drab plumage, small body size, frequently upturned tails, and a magnificent, bubbling song. Of the four species of Wren known to occur on Vancouver Island, the Pacific Wren is the smallest and most rotund, weighing between 8-12 g and with a wingspan of 12-16 cm (Pacific Wren Identification, n.d.). It is virtually indistinguishable from the closely related Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis), although a trained ear may be able to differentiate them by song (Toews & Irwin, 2020). Fortunately, the Winter Wren does not occur in southern British Columbia (Winter Wren Range Map, n.d.).

The Pacific Wren is a dark, uniform brown colour across its entire body, with a short tail and heavily barred flanks. Only the supercilium, chin and throat are slightly paler; the supercilium is more conspicuous than that of a House Wren, but much less so than that of a Marsh or Bewick’s Wren. Each of these three species can be uniquely differentiated from the Pacific Wren by comparing characters such as size, plumage, and habitat.

a) Compared to the Pacific Wren, the House Wren (Troglodytes aedon) will be larger and paler (particularly on the underside), with a longer tail and a grayer throat and breast (Johnson, 2020). The House Wren is the least common of our four local Wrens, and is generally somewhat tolerant of urbanization (Lumpkin & Pearson, 2013; Newhouse et al., 2008). Photo: Mitchell Goldfarb, 2021

b) Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii) is noticeably larger than the Pacific Wren, with a pale grey underside contrasting with brown upperparts. The tail is long and barred, with white speckling on the distal tips, though it is best distinguished by a very distinctive white supercilium (Kennedy & White, 2020). Bewick’s Wrens are more commonly encountered and prefer drier, more open woodland compared to the Pacific Wren (American Ornithologist’s Union, 1983). Photo: Gavin Aquila, 2024.

c) The Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris) is approximately the size of a House Wren, with a cinnamon-coloured rump and scapulars and a triangular black-and-white blotch on it’s back. Occasionally it has faint ventral barring, but generally the underside is a pale white with buffy flanks. Like the Bewick’s Wren, it has a distinct white supercilium, however the Marsh Wren also possesses a black crown (Kroodsma & Verner, 2020). Unlike the Pacific Wren, the Marsh Wren is found predominantly in wetland areas where it nests amongst bulrushes and cattails (Leonard & Picman, 1987). Photo: Will Cihula, 2024.

Vocalization

Gram-for-gram, there is perhaps no other bird in British Columbia that is able to produce a song of such length and complexity as the Pacific Wren, besides its sister species, the Winter Wren. Their songs are highly complex and can be extremely variable in length, but usually range between 5 and 10 seconds of trilling, bubbling notes that climb and then tumble repeatedly in tone (Pacific Wren Sounds, n.d.):

Life History

Habitat & Distribution

In the breeding season (April – July), the Pacific Wren is most at home near flowing water in the riparian zone of old-growth or mature second-growth forests, where fallen logs are abundant (Waterhouse, 1998). Breeding presence is strongly correlated to salmonid returns in local streams (Field & Reynolds, 2011), where it is thought that the nutrient deposition from one autumn would contribute to increased invertebrate abundance the following summer (Christie & Reimchen, 2008). Mature stands of forest are preferred because they tend to have abundant deadwood, which is important for foraging for arthropods; the greatest abundance of Pacific Wrens are generally found in those stands that exhibit the most structural complexity, not simply the oldest (Waterhouse, 1998). Nonbreeding birds tend to remain associated with dense woody vegetation, but do not restrict themselves to mature forests as heavily (Toews & Irwin, 2020).

Foraging & Locomotion

The Pacific Wren is an erratic, nervous forager that has been frequently referred to as “mouse-like” in habit, as it diligently searches by “skipping” (Grinnell & Storer, 1924) and hopping through root tangles, hollows and stream banks for small arthropods to glean from the ground or from low vegetation (Bent, 1948). It has a particular taste for spiders, caterpillars, and beetles (Van Horne & Bader, 1990).

Breeding & Nesting

Pairing usually begins in April, when males begin to establish their territories along stream banks, which they claim and defend by countersinging, or “vocal dueling”, with neighboring males (McLachlin, 1983). In addition to using their voice to drive off potential rivals, it is also used to attract females (Bent, 1948). Polygyny is also observed somewhat frequently, though the majority of individuals in most populations are monogamous (McLachlin, 1983).

Suitable nesting sites are generally close to the ground, but can be highly variable in regards to the structure they make use of and their particular form. Nests have been observed under the banks of creeks, amongst the roots of overturned trees, and within tree hollows, but also have been found in hanging moss or even tree branches. The nests themselves are fully enclosed, domed structures, constructed primarily of mosses, twigs, bark, feathers, and other fibrous materials (Bent, 1948; Heath, 1920).

Egg laying usually lasts from April to July, with a clutch size ranging from 1 to 10 eggs, and an incubation period of about 14 days. After hatching, both parents will feed the young for potentially up to a month; about 2 weeks until fledging, and about another two weeks after fledging. The only exception to this is if the female lays another clutch; in this case she will be preoccupied with incubating the new clutch and the male will take up the sole responsibility for feeding the fledglings (Bent, 1948).

Conservation

Overall population trends in Canada are relatively steady (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2019), however because of their preference for mature forests, they are particularly susceptible to habitat degradation, primarily as a result of forestry practices. Forest fragmentation and homogenization of forest structure through same-age stand management is expected to contribute to future declines in the abundance of Pacific Wrens (Manuwal, 1991). With that said, there is evidence to suggest that the effects of logging on Pacific Wren populations can be at least partially mitigated if these complex old-growth features are retained after logging (Zarnowitz & Manuwal, 1985).

Research: Another Taxonomic Puzzle

For decades, the Pacific Wren was considered to be conspecific with the Eurasian Wren and the Winter Wren, but in 2010 this was amended by the American Ornithological Society’s Check-List of North American Birds, the primary taxonomic authority on North American birds (Chesser et al., 2010). Where formerly, these three species were considered to be Troglodytes troglodytes, the Winter Wren, it was now split into three distinct species: the Winter Wren was renamed to T. hiemalis, the Pacific Wren to T. pacificus, and the Eurasian Wren retained the original name T. troglodytes.

So what was the justification for this reorganization?

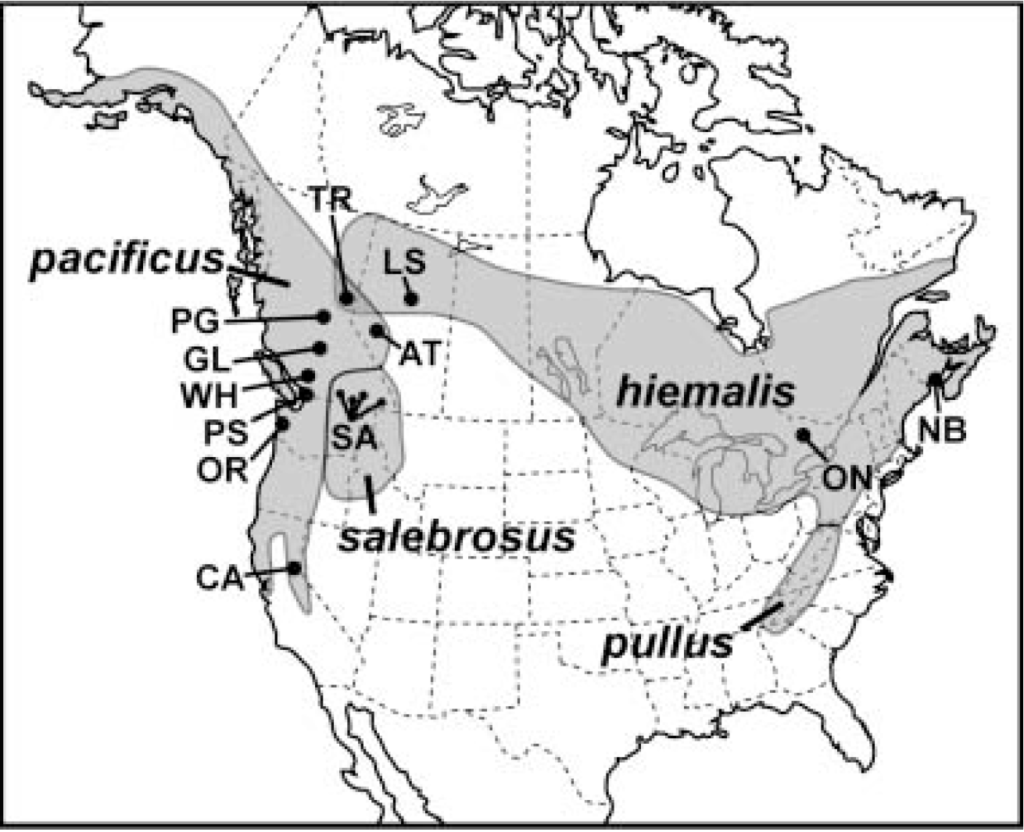

Although it was based on several papers investigating the complex biogeography of the Troglodytes complex at the time, the most noteworthy study was one which first resolved T. pacificus as distinct from the other two. In eastern British Columbia, Toews & Irwin (2008) identified a region where the range distributions of T. pacificus and T. hiemalis overlap and they occur sympatrically, sometimes even with neighboring territories. What was remarkable was that the two populations within this area did not interbreed and, more importantly, had distinct variations in song, hereafter designated the western and eastern singing types (though it is worth noting that “distinct” does not mean easily distinguished by ear). Following this lead, they compared mitochondrial DNA sequences within and between these two “singing forms”, and found that the western-singing and eastern-singing birds were genetically separate from one another.

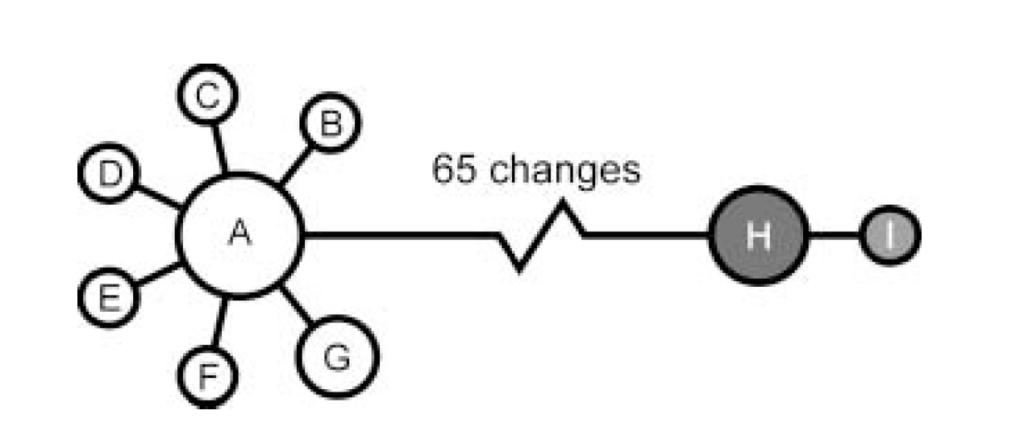

From the 12 western-singing birds the researchers sampled from, they identified 7 haplotypes (groups of alleles inherited together from a single parent) that differed from each other by no more than 2 base pairs. From the 4 eastern-singing birds they sampled, they identified 2 haplotypes that differed by only 1 base pair. When these two groups of haplotypes, or haplogroups, were compared to each other, however, they differed by about 65 base pairs, further indicating that these were two genetically distinct groups that are probably separate species.

Determining the position of the Eurasian Wren involved more studies, but ultimately it was determined that T. pacificus is the most basal of the three, having split from the other two approximately 4 million years ago (Toews & Irwin, 2008), with T. troglodytes and T. hiemalis splitting approximately 2 million years ago (Drovetski et al., 2004). With all that said, the taxonomic position of the entire wren family has been in constant flux and will likely be subject to further revision, particularly in regards to the placement of the genus Troglodytes in relation to the rest of the Troglodytidae.

And let’s not even get into all the different subspecies!

References

American Ornithologists’ Union. (1983). Check-list of North American birds : the species of birds of North America from the Arctic through Panama, including the West Indies and Hawaiian Islands / prepared by the Committee on Classification and Nomenclature of the American Ornithologists’ Union. American Ornithologists’ Union. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.50892

Bent, A. C. (1948). Life Histories of North American Nuthatches, Wrens, Thrashers, and Their Allies: Order Passeriformes. Bull. US. Natl. Mus., 195, 1–475. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.03629236.195.1

Chesser, R. T., Banks, R. C., Keith, B. F., Cicero, C., Dunn, J. L., Kratter, A. W., Lovette, I. J., Rasmussen, P. C., V, R. J., Rising, J. D., Stotz, D. F., & Winker, K. (2010). Fifty-First Supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union Check-List of North American Birds. The Auk, 127(4), 966–966. https://doi.org/10.1525/auk.2010.127.4.966

Christie, K. S., Hocking, M. D., & Reimchen, T. E. (2008). Tracing salmon nutrients in riparian food webs: isotopic evidence in a ground-foraging passerine. Can. J. Zool., 86(11), 1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.1139/z08-110

Drovetski, S. V., Zink, R. M., Rohwer, S., Fadeev, I. V., Nesterov, E. V., Karagodin, I., Koblik, E. A., & Red’kin, Y. A. (2004). Complex biogeographic history of a Holarctic passerine. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 271(1538), 545–551. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2003.2638

Environment and Climate Change Canada. (2019). Population Status: Pacific Wren. Status of Birds in Canada, Data Version 2019. https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/tendance-trend-eng.aspx?sY=2019&sL=e&sB=PAWR&sM=p1&sT=7ba87a11-baa0-4466-a47d-55b967b3ff1c

Field, R. D., & Reynolds, J. D. (2011). Sea to sky: impacts of residual salmon-derived nutrients on estuarine breeding bird communities. Proc. Biol. Sci., 278(1721), 3081–3088. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.2731

Grinnell, J., & Storer, T. I. (1924). Animal Life in the Yosemite: An Account of the Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, and Amphibians in a Cross-Section of the Sierra Nevada. University of California Press, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/grpo/index.htm

Heath, H. (1920). The Nesting Habits of the Alaska Wren. The Condor, 22(2), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/1362421

Johnson, L. S. (2020). House Wren (Troglodytes aedon), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.houwre.01

Kennedy, E. D. and D. W. White (2020). Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.bewwre.01

Kroodsma, D. E. and J. Verner (2020). Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.marwre.01

Leonard, M. L., & Picman, J. (1987). Nesting Mortality and Habitat Selection by Marsh Wrens. The Auk, 104(3), 491–495. https://doi.org/10.2307/4087548

Lumpkin, H. A., & Pearson, S. M. (2013). Effects of exurban development and temperature on bird species in the southern Appalachians. Conserv. Biol., 27(5), 1069–1078. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12085

Manuwal, D. (1991). Spring bird communities in the southern Washington Cascade Range. In Ruggiero, L., K. Aubry, A. Carey, and M. Huff (eds.). Wildlife and vegetation of unmanaged Douglas-fir forests. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-285. U.S. Forest Service, Pacific NW Forest and Range Exp. Station, pp 161-174. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281017906_Spring_bird_communities_in_the_southern_Washington_Cascade_Range_In_Ruggiero_L_K_Aubry_A_Carey_and_M_Huff_eds_Wildlife_and_vegetation_of_unmanaged_Douglas-fir_forests_Gen_Tech_Rep_PNW-GTR-285_US_Fores

McLachlin, R. A. (1986). Dispersion of the western winter wren (Troglodytes troglodytes pacificus (Baird)) in coastal western hemlock forest at the University of British Columbia Research Forest in south-western British Columbia [Doctoral Dissertation, University of British Columbia]. National Library of Canada. https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/services/services-libraries/theses/Pages/item.aspx?idNumber=1006333624

Newhouse, M. J., Marra, P. P., & Johnson, L. S. (2008). Reproductive Success of House Wrens in Suburban and Rural Landscapes. Wilson J. Ornithol., 120(1), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1676/06-156.1

Pacific Wren Identification (n.d.). All About Birds. Retrieved October 9, 2024. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Pacific_Wren/id

Pacific Wren Range Map (n.d.). All About Birds. Retrieved October 9, 2024. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Pacific_Wren/maps-range

Pacific Wren Sounds (n.d.). All About Birds. Retrieved October 9, 2024. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Pacific_Wren/sounds

Winter Wren Range Map (n.d.). All About Birds. Retrieved October 9, 2024. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Winter_Wren/maps-range

Toews, D. P. L. and D. E. Irwin (2020). Pacific Wren (Troglodytes pacificus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.pacwre1.01

Van Horne, B., & Bader, A. (1990). Diet of Nestling Winter Wrens in Relationship to Food Availability. The Condor, 92(2), 413–420. https://doi.org/10.2307/1368238

Waterhouse, F. L. (1998). Habitat of Winter Wrens in Riparian and Upland Areas of Coastal Forests. [Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University]. https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk2/ftp01/MQ37660.pdf

Zarnowitz, J. E., & Manuwal, D. A. (1985). The Effects of Forest Management on Cavity-Nesting Birds in Northwestern Washington. J. Wildl. Manag., 49(1), 255–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/3801881

Great job Marcel! I am glad you did the Pacific Wren justice after beating me to picking it! I found the information about the separation of classifying the Winter Wren into three distinct categories very interesting. This must have been difficult to discover because they look exactly the same. Do you know if there is a way to visually tell the Pacific Wren apart from the Winter Wren in the hand, as I imagine it would be near impossible from a distance? I can imagine what a pain it would be to catch one of the two species in their overlapping territory and have to figure out which species it is.

Hi Bekah,

There are, supposedly, slight differences in plumage, primarily being that the Pacific is a darker, richer brown overall. Winter wrens also have a slightly paler throat than the Pacific Wren, and the white spots on the greater coverts are more defined and well-contrasting in the Pacific Wren compared to the Winter. Luckily, field differentiation between them is only going to be necessary in that overlap region of eastern BC; they do not occur sympatrically anywhere else, as far as we are aware. I would, however, caution that these identifying features I mentioned will probably overlap significantly between the two species; even in the hand, it would likely take a very good eye to distinguish them.

Thank you for the response Marcel! I can kind of see the difference in photos of the Pacific Wren and the Winter Wren now that you have pointed that out. They are still so similar though. I would still dread catching them if I was banding in their overlapping territory!

Nice blog, Marcel! Thanks for the ID tips!! As you mentioned, wrens are famous for their singing, and I wondered if female wrens sing like the males. As you said in your blog the males sing to attract females; do the females repeat the song back? or do they have their own unique song? Thanks!

Hi Emma,

Interestingly enough, there is no information in the literature on singing in females; only males sing in the case of Bewick’s and Marsh Wrens, however in House Wrens, paired females will sing short songs in response to the songs of their mate. Perhaps that is something to explore ourselves this coming spring!

Interesting, I guess it might be tough to observe in the wild because they aren’t sexually dimorphic.

Thanks,

Emma