If you live on a coast of North America, you’ve probably seen a dark, little goose around and wondered “What is wrong with that Canada Goose.” The answer is nothing! The bird you’ve seen is likely to be a Branta bernicla, or Brant, a coastal bird who knows how to have so much fun that it’s got its own festival. This is a bird that knows how to party.

Brant: Characteristics & Life History

Identification

The Brant, like all geese, are taxonomically categorized into the family Anatidae and the Order Anseriformes, which fall under the umbrella of the Class Aves-the bird class (Sibley, 2016). Therefore, as with all birds, they are easily identifiable from other types of animals by their wings, bills, and their ability to walk upright.

To separate Brant from other birds is a bit more of a difficult task. Anatidae geese are very similar in general shape and demeanor to each other. Common traits that they share are having their webbed feet situated right in the middle of their body to allow ease of mobility on land, a stubby bill and a curved neck. They are generally on the larger side for being birds, about the size of a small to medium dog. Additionally, they, as waterfowl, are typically found near bodies of water.

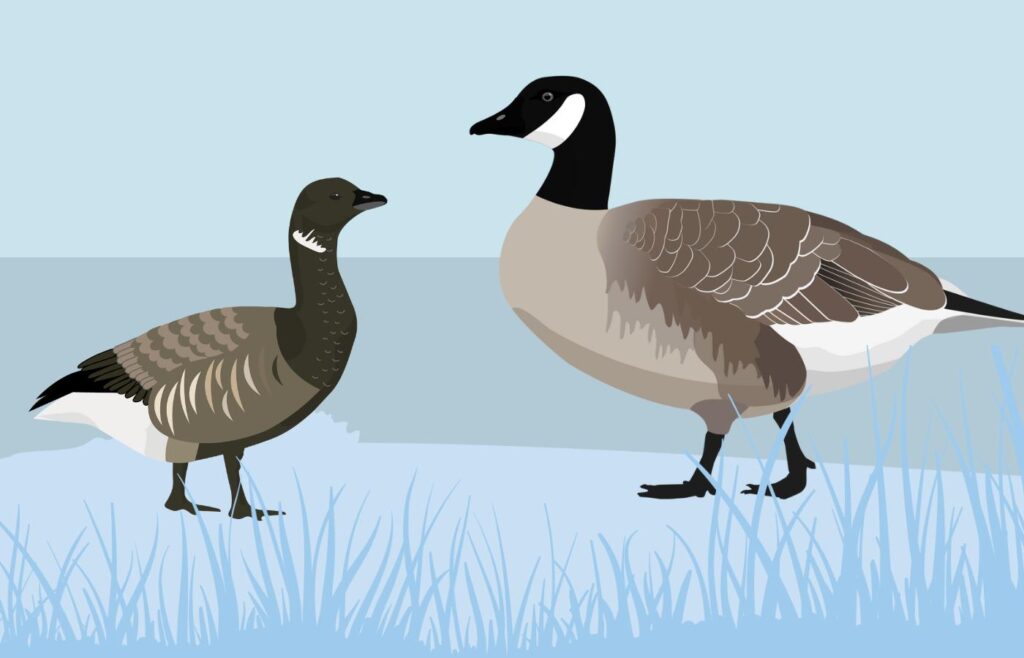

Brant do have a few unique features which allow identification, once the art of recognizing geese is mastered. They are a smaller species of goose. Brant sizing ranges from being about 56-63 cm in length and have a weight range of about 1000 to 1700 grams (Cornell Lab, 2024). As can be seen in Figure 1 below, this is much smaller than the stereotypical Canada goose that many people think of when they hear goose. Other unique features of the Brant include its dark head and neck that extends to its chest, its very white undertail, and the eye-catching white necklace that doesn’t quite wrap all the way around.

The other features of the Brant are not quite so unique and actually tend to vary within the species itself. You see there are multiple subspecies within the species “Brant”. The exact number of subspecies is a hotly debated topic within ornithology circles. Many birding associations list only three, but the Canadian government has divided the Brant of their country into four distinct breeding populations that are occasionally used interchangeably as subspecies (British Waterfowl Association, 2024;Canadian Wildlife Service, 2018). Precise identification of the different subspecies is a bit difficult without genetic analysis, so generally, Brant are ID’ed based on the colouration of their bellies and the fullness of their necklace (Wilson et al., 2024). Most tend to stick with three common subspecies when analyzing Brant: the black Brant, which have the darkest stomach feathers and the most complete necklace, the dark-bellied Brant with stomach feathers that are grayer than those of the black Brant and a slightly smaller necklace, and finally the light-bellied Brant (or pale-bellied) which have a very light stomach and a very small necklace. Figure 2 contrasts the different subspecies.

A fun fact about Brant identification: In Western Europe, they are called Brent Geese.

Vocalization

The call of Brant is rather distinct. Rather than a honk like many geese species, Brant produce a rolling “ruk-ruk” sound.

As can be heard in Audio 2, an entire flock of Brant can produce an overwhelming sound. Your neighbours will appreciate a lowered volume while listening to these birds.

Audio 2. Flock of Brant Calling. Credit: Audubon

Younger Brant, chicks and juveniles, have been known to produce the stereotypical “peep” common to goslings (Cornell Lab, 2024)

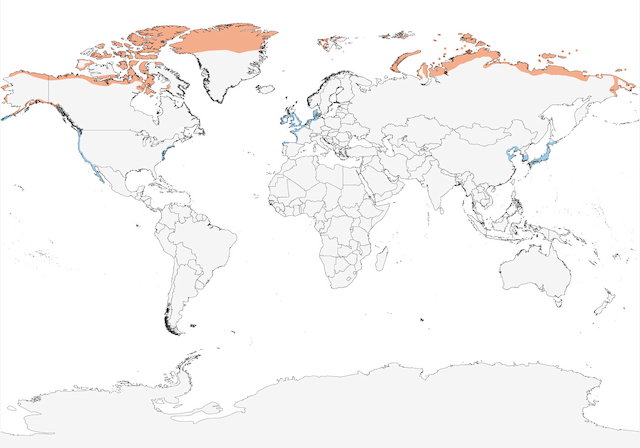

Distribution Range +Migration

As can be seen in Figure 3, Brant populations are distributed across the Northern Hemisphere. Black Brant and light-bellied Brant breed along the northern most edges of Canada, Alaska and Russia. When fall arrives, these birds will travel thousands of kilometers to winter along the lower coasts of North America (Ward et al., 2005). Some will even spend the winter in Puget Sound, just a little south of Vancouver Island (Figure 4). On the Atlantic side, Brant will breed within the Eastern Canadian Artic and then may winter anywhere from Massachusetts to Ireland. Typically, the migrating birds will follow the coastlines, so birds that breed on the Pacific side of the continent will winter there as well and vice versa (Ward et al., 2005).

Alternatively, dark-bellied Brant make their nests and raise their young near the Taymyr Peninsula of Siberia, located in the middle of the northern coast, and will fly down to the warmer climates of France and England to spend their winter (Cornell Lab, 2020).

Habitat

Through their lives, Brant will occupy a large variety of habitats at many different latitudes. When nesting in the lower Artic, these geese settle in large colonies along the edges of salty marshland. Farther up, the Brant form smaller colonies or even live as solitary pairs on deltas or on the shores of small islands (Cornell Lab, 2024). Intertidal zones and lagoons are popular choices for Brant during winter. The more eelgrass (Brant’s favoured vegetation) present in an area, the more enticing a shoreline is to these birds (Cornell Lab, 2020). During migration, Brant may discard its typical choice of saltwater habitats in favour of freshwater lakes within the land-locked continent that they are crossing (Aubudon, n.d.).

Behaviour

Mating + Nesting

As previously mentioned, Brant are for the most part colonial breeders who build their nests in close proximity. Following maturation (around second year), female Brant will often return to the colony where they were born (natal philopatry) to breed whilst males will disperse to find new colonies. Once chosen, they do not typically change colony location from year-to-year (Lindberg et al., 1998). Brant are considered a monogamous species, they mate for life, however that does not mean they don’t see other birds on the sly. One study found that an estimated 8% of nestlings were from extra-pair copulations (breeding outside mated pair) (Leach et al., 2020)

Once mated, the pair will produce between 3 to 5 eggs per clutch. The eggs hatch within the month and then the chicks fledge within two more. Baby Brant will stay with their parents from their hatching until the end of their first winter (Cornell Lab, 2024).

Feeding + Diet

Brant display two types of foraging behaviour: they graze and they dabble. Dabbling is an action many waterfowl do where they tip themselves over to feed on vegetation just below the surface of the water and they leave the end of their tail high in the air. A great example of this action can be seen in Video 1. While foraging, the Brant are feeding upon vegetation-they are a herbivorous species- and the content of their diet shifts depending on where they are. During non-breeding seasons in the south, they feed almost exclusively on eelgrass. The rest of the time their diet is less restrictive, and they will feed upon a variety of sea- or freshwater grasses, pondweed and even some mosses (Cornell Lab, 2024).

Conservation Status

International Red List

On an international level, Brant have not been identified as a species of great conservation concern. The IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, assessed the Brant as a species as recently as 2020 and found the populations fit the criteria of Least Concern (IUCN, 2020). The Least Concern Status is given to species that do not show severe signs of decline and do not fulfil the criteria of the other, more serious statuses (BirdLife International, n.d.). Consequently, the IUCN has decided increased species protection is unneeded.

Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife

On a smaller-scale, certain regions have taken the liberty to apply more serious conservation statuses to their Brant species. The Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife has deemed the local Brant subspecies, Western High Artic, a “Species of Greatest Conservation Concern” and has increased the regulations on hunting the species as well as restricted hunting in zones of high migratory traffic (Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, 2024)

Cultural Importance

The Party of the Year

Every year, for the months of spring, thousands of Brant migrate up the west coast of North America to reach their breeding grounds in the northern lands of Alaska. Before they reach their destination, however, they make a pit-stop on the beaches near Parksville-Qualicum, Vancouver Island for a taste of the local cuisine, a relaxing stay at the world-famous spas and to party like there’s no tomorrow. Just Kidding! Birds aren’t allowed at the spa, but they can party!

For the past 30 plus years, the coastal communities of Qualicum Beach and Parksville have played host to the Brant Wildlife Festival. This multi-week-long event celebrates the tens of thousands of birds who have travelled many thousands of kilometers to get there. The organizers have even managed to convince the cities to close their beaches to dogs for the duration of the migration.

There are so many fun and informative things to do at this festival. Figure 6 shows the list of 2023 events. They range from the “Lift Off” party as the opening night to taking bird-watching tours to having a movie night. There is really something for everyone and even going to one event helps support a great cause. Who wouldn’t want to party with some great birds?

Figure 6. 2023 Schedule of the Brant Wildlife Festival in Parksville/Qualicum Beach, BC. Source: (Brant Wildlife Festival, 2023)

Current Research

Climate Change Effects on Migration

As with many people, climate change has been at the forefront of the minds of ornithologists. For those with a focus on Branta bernicla, the question of how climate change will impact Brant populations and what factors will be the most influential is essential for the continual management and protection of these birds. Recently, there have been quite a few investigations into eelgrass as a factor on Brant populations.

Eelgrass, specifically Zostera marina, is an essential plant for Brant. During non-breeding season, when Brant are in their southern territories, they feed primarily on the Zosteria; it is in fact a unique trait among birds to rely so heavily on a single food source during winter (Cornell Lab, 2020). Unfortunately, eelgrass abundance has seen significant declines over the past couple years due to rising oceanic temperatures and decreasing water clarity (Lefcheck et al., 2017). Therefore, it has become increasingly important to explore the effects that abundance of their favoured food source will have on Brant populations.

One of the latest studies focused their attention on how reduced eelgrass availability affects Brant migration (Stillman et al., 2024). As previously mentioned, Brant migrate very long distances, from Mexico to the Artic, so the team hypothesized that a decreased abundance of eelgrass would negatively impact the energy stores of Brant thus reducing their ability to survive migration. It was found that, while decreased availability of eelgrass did negatively impact Brant populations to a degree, the situation was a lot more complicated than they assumed. Their experiment did not account for Brant population density nor that the birds would compensate for diminished eelgrass fields by increasing feeding on other sources. They concluded that Brant had difficulty migrating when the eelgrass biomass (total quantity) was below a certain point, but that more research was needed to be done on the subject. It just goes to show that environmental studies are complicated and that it is important to extensively study species to properly manage them as climate change’s effects escalate.

Thank you for taking the time to read about the Magnificent Brant. If you have any questions, had a cool fact you want to share or just want to say hello, please leave a comment down below!

References

Aubudon. (n.d.) Brant: Behaviour. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/brant

Aubudon. (n.d.). Migration Map of Brant [Photograph]. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/brant

Aubudon. (2024). Flock Flying Overhead [mp3]. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/brant

Bird Aware Solent. (2024). A brent goose and a much larger Canada goose with a bolder chin strap [Photograph]. Bird Aware. https://birdaware.org/solent/meet-the-birds/geese/dark-bellied-brent-goose/

Birdland Unlimited. (2023). Brant Geese Hungry for Seaweed and Brant Call | USA [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X9qwPXBaDbA

BirdLife International. (n.d.). The IUCN Red List: identifying the birds that most need our help. BirdLife. https://www.birdlife.org/projects/iucn-red-list/

Brant Wildlife Festival. (n.d.). Brant Hatchling [Photograph]. https://brantfestival.bc.ca/learn-about-brant-geese/

Brant Wildlife Festival. (2023). Brant Handout Schedule 2023 [pdf].https://brantfestival.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/Brant-Handout-Schedule-2023-final-2.21.23.pdf

British Waterfowl Association. (2024). Brant Goose. Waterfowl.org. https://www.waterfowl.org.uk/wildfowl/swans-geese-allies/brent-goose/

Canadian Wildlife Service. (2018). Brant (Branta bernicla). Government of Canada. https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/oiseau-bird-eng.aspx sY=2019&sL=e&sB=BRAN&sM=a#:~:text=Brant%20are%20Arctic%2Dnesting%20geese,the%20Canadian%20Eastern%20Low%20Arctic.

Cornell Lab. (2020). Brant Branta bernicla. Birds of the World. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/brant/1.0/introduction

Cornell Lab. (2024). Brant Life History. All About Birds. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Brant/lifehistory

Cornell Lab. (2024). Brant Identification. All About Birds. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Brant/id

Cornell Lab. (2024). Brant Sounds. All About Birds. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Brant/sounds

Cornell Lab. (2020). Distribution of Brant. Birds of the World. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/brant/cur/distribution

Cornell Lab. (2020). Distribution of Brant [Photograph]. Birds of the World. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/brant/cur/distribution

Cornell Lab. (2020). Brant Habitat. Birds of the World. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/brant/1.0/habitat

IUCN. (2020). Brent Goose. IUCN Red List. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22679946/189780266

Leach, A. G., Riecke, T. V., Sedinger, J. S., Ward, D. H., & Boyd S. (2020). Mate fidelity improves survival and breeding propensity of a long-lived bird. J Anim Ecol. 89(10), 2290–2299.https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1111/1365-2656.13286

Lefcheck, J.S., Wilcox, D.J., Murphy, R.R., Marion, S.R. & Orth, R.J. (2017). Multiple stressors threaten the imperiled coastal foundation species eelgrass (Zostera marina) in Chesapeake Bay. USA. Glob Change Biol, 23(9), 3474-3483. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1111/gcb.13623

Lindberg, M. S., Sedinger, J. S., Derksen, D. V. & Rockwell, R. F. (1998). Natal and Breeding Philopatry in a Black Brant, Branta bernicla nigricans, Metapopulation. Ecology, 79(6), 1893–1904. https://doi.org/10.2307/176697

Ooms, A. (n.d). Brant on Beach [Photograph]. Brant Wildlife Festival. https://brantfestival.bc.ca/gallery/

Sibley, D. A. (2016). The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America (2nd ed.) Alfred A. Knopf, NY. pp. 2, 5.

Stillman, R. A., Rivers, E. M., Gilkerson, W., Wood, K. A., Clausen, P., Deane, C., & Ward, D. H. (2024). Predicting the response of a long-distance migrant to changing environmental conditions in winter. Ecology and evolution, 14(7), e11619. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.11619

VIMS. (n.d.). An oblique aerial photograph of underwater grass beds in Chesapeake Bay [Photograph]. VIMS. https://www.vims.edu/about/at_a_glance/photo_galleries/sav/

VIMS. (n.d.) Eelgrass Meadow [Photograph]. Virginia Institute of Marine Science. https://www.vims.edu/about/at_a_glance/photo_galleries/sav/

Ward, D.H., Reed, A., Sedinger, J.S., Black, J.M., Derksen, D.V. & Castelli, P.M. (2005). North American Brant: effects of changes in habitat and climate on population dynamics. Global Change Biology, 11(6), 869-880. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.00942.x

Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife. (2024). WASHINGTON Game Bird and Small Game Hunting Regulations. eRegulations, p 57. https://www.eregulations.com/assets/docs/resources/WA/24WAWF_LR5.pdf

Wilson, R. E., Boyd, W. S., Sonsthagen, S. A., Ward, D. H., Clausen, P., Dickson, K. M., Ebbinge, B. S., Gudmundsson, G. A., Sage, G. K., Rearick, J. R., Derksen, D. V., & Talbot, S. L. (2024). Where east meets west: Phylogeography of the high Arctic North American brant goose. Ecology and evolution, 14(4), e11245. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.11245

Wroza, S. (2017). Branta bernicla bernicla [mp3]. https://xeno-canto.org/397450

I really like the rhythm of your writing; it felt really personal and was a joy to read!

I had no idea about the three (or four?) subspecies. I’m curious if there have ever been sightings of the dark-bellied ssp. here in Nanaimo?

Also, I wonder if the lack of eelgrass is impacting all three subspecies to the same extent? I’m glad that more conservation efforts are including eel grass planting as a part of their marine habitat restoration plans.

I’m definitely going to the festival next year…sounds like an amazing time!!

Thanks again for the great read 🙂

Hi Alysia,

I am glad you liked the writing style.

To answer your questions, it is very unlikely that dark-bellied brant have been seen in Nanaimo. They are mainly seen around Europe and Upper Russia. If any have been sighted in Canada then they will be some very lost geese.

As for the eelgrass, that is an excellent question whose answer goes back decades. In the 1930s, there was massive declines in eelgrass abundance in the Atlantic Ocean, particularly in the Hudson Bay, due to a wasting disease. As a consequence, the Light-bellied brant populations were severely impacted to the point where some studies estimate only 20% survived. Similar effects were recorded in Dark-bellied populations in Europe. However, Black brant populations on the West Coast on North America were not recorded to have declined as the disease did not seem to spread to the Pacific. The light- and dark-bellied brant populations have increased since then, but never quite recovered and neither did the atlantic eelgrass. So, to answer your question directly, the lack of eelgrass does not affect the subspecies evenly. Its effects are much more felt by the Atlantic subspecies.

Awesome Blog post Grace! I’ve wanted to look more into these species for awhile now, this was a great way to read up on them. I was wondering why the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife has deemed Brant Geese conservation to be of greatest concern if most of the world considers them of least concern? Is this due to excessive hunting of the species in this location in the past?