Introduction:

Common name: Spotted Sandpiper

Scientific name: Actitis macularius

Order: Charadriiformes

Family: Scolopacidae

Widely spotted across North and Central America, this little shorebird, Actitis macularius is known as the Spotted Sandpiper. It stands out with its distinctive features and quirky behaviour, making it a favourite among bird watchers and ornithologists.

Description and Identification

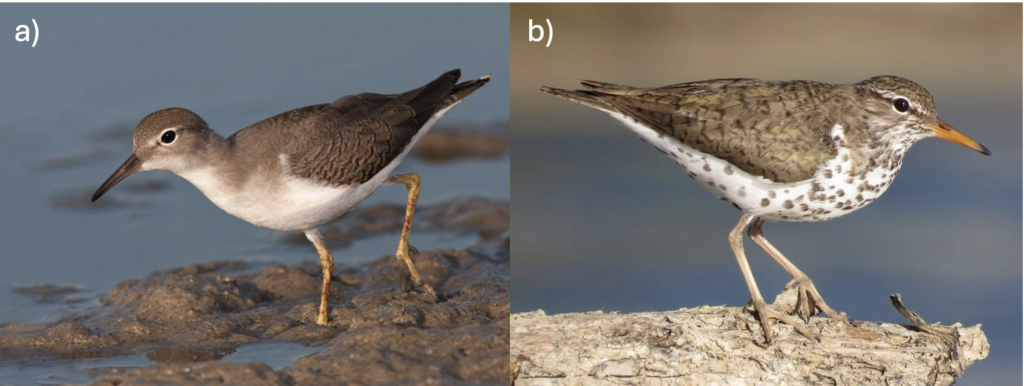

The Spotted Sandpiper is a medium-sized bird, roughly the size of an American Robin; but more precisely their body length is 18-20 cm with a wing span of approximately 37 cm (14.5 inches) (All About Birds). In the non-breeding season, the Spotted Sandpiper has a brown/grey back, a bright white breast, and bright yellow legs (All About Birds). Unlike their legs, their beaks rock a much more pale yellow/orange colour with a black tip (All About Birds).

If you’re lucky enough to catch a glimpse of these guys in flight you will also notice a distinct white band along their wings (All About Birds).

During the breeding season, the Spotted Sandpiper earns its name with their striking dark spots that take over their previously white belly and their back becomes increasingly more brown and bill more orange. These fantastic birds also have a striking brown line through their eye line, followed by a white line above.

Credit: Gail from Flickr

© Ian Hearn Macaulay Library Idaho, June 21, 2017 © Darlene Friedman Macaulay Library

Figure 1: a) Adult Spotted Sandpiper in non-breeding plumage (Photo by Ian Hearn). b) Adult Spotted Sandpiper in breeding plumage (Darlene Friedman).

Besides identification by colour, these birds can also be easily identified by their fantastic dancing or quirky characteristic of teetering, known as a constant bobbing of their tail as they forage. This characteristic makes them easy to identify year-round without the trouble of breeding and non-breeding plumage (All About Birds). However, the reason behind this behaviour is not fully yet understood.

A glimpse into the dance moves these birds have…

Figure 2. Spotted Sandpiper Teetering, Credit: Wandering Sole Images

Distribution and Habitat

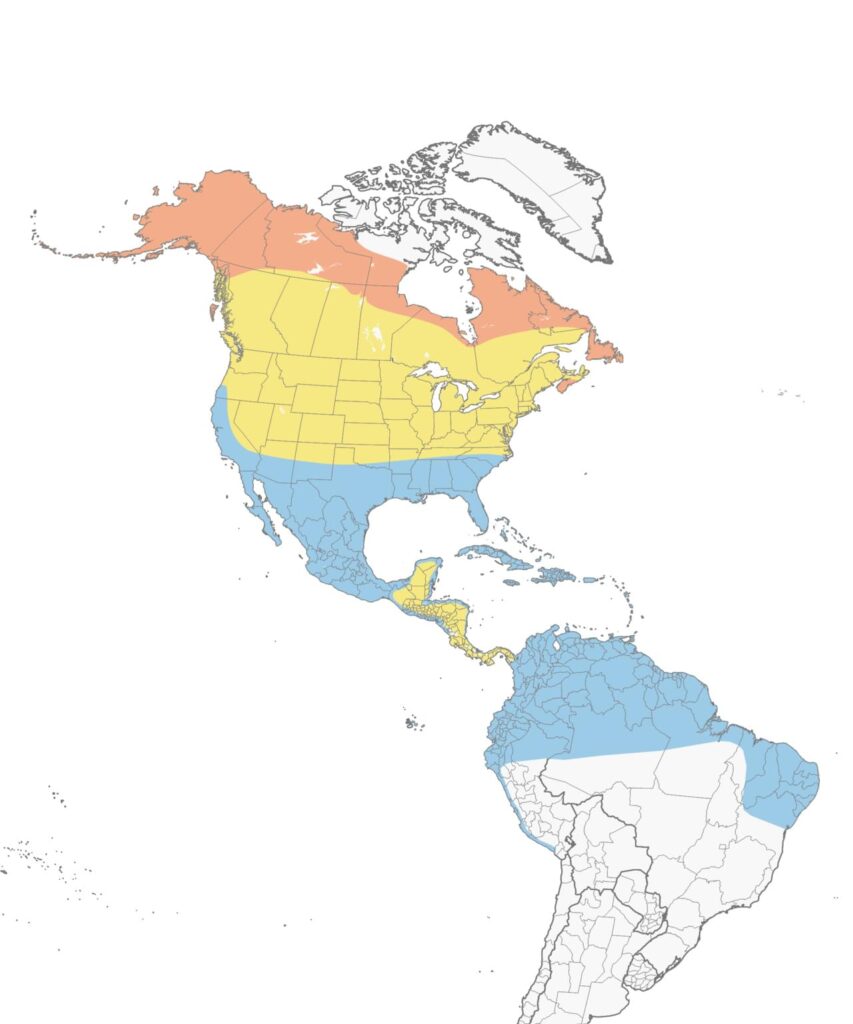

The Spotted Sandpiper has one of the most broad distributions of shorebird species in North America, it is basically a better version of Christopher Columbus in the shorebird world. It breeds across North America, from the frozen tundra of Alaska to the bustling cities of the southern U.S., and then spends its winters in the tropics, but honestly, who wouldn’t (All About Birds)? From Central America to the northern tip of South America, this bird knows how to chase the sun (All About Birds).

These terrific shorebirds don’t discriminate either when it comes to habitat, they can be seen in freshwater habitats such as riverbanks, lakeshores, streams, and marshes as well as coastal shorelines allowing for a large range of elevation (All About Birds). Their nests can be found within close proximity to any of these bodies of water and tend to be among dense shrubs for safety from predators (All About Birds). The nest itself is begun by the female and consists of a roughly three-inch depression in the ground coated with dead grass (All About Birds).

Figure 3. Geographic distribution of Spotted Sandpipers, (Year-round is purple, Breeding is orange, Migration is yellow and, Non-breeding is blue) (All About Birds).

Behaviour

The Spotted Sandpiper exhibits several unique behaviours, the most notable being their mating behaviour. As you are about to learn, The Spotted Sandpipers play the dating game a little differently, the females run the show, often collecting multiple partners while the males dutifully manage most of the child-rearing duties in what is called reversed sexual dimorphism and polyandry (Oring et al. 1991). Initially, females will pair monogamously but, as new males arrive, the competition for mates increases (Maxson & Oring, 1980).

Unlike most bird species, the female Spotted Sandpiper is larger and more dominant, she takes the lead in establishing territories and courting males (Blizard, 2017). This increase in dominance has been found to correlate with testosterone which increases for females during courtship and incubation and then remains steady, whereas the males’ levels soon plummet after courtship (Blizard, 2017). After laying their eggs, the female often leaves the male to incubate the eggs and raise the chicks, allowing her to mate with other males during the same breeding season (Blizard, 2017).

In addition to its mating behaviours, this species is also known for its distinctive flight pattern of stiff/shallow wingbeats with short bursts of flight low over the water (Willis, 1994).

Its foraging style involves walking along the shoreline or in shallow waters, picking up insects, small fish, and crustaceans via rapid probing, stitching and jabbing (Reed et al. 2020). On rare occasions, the Spotted Sandpiper can even be seen going for shallow dives to escape predation (Stone, 1925).

Credit: Linda Freshwaters Arndt

Not only are the Spotted Sandpipers dancers but they are also singers! Just maybe not as good as their dance moves. They have a few songs that they use for courtship as well as communication which consist of many “weet” calls with multiple trills and whistles (All About Birds). They also have alarm calls that have fewer notes but that gain in intensity (All About Birds).

Songs:

Audio 1. Spotted Sandpiper Song Example One. Credit: (Audubon).

Audio 2. Spotted Sandpiper Song Example Two. Credit: (Audubon).

Alarm Calls:

Audio 3. Spotted Sandpiper Alarm Call Near Nest. Credit: (Audubon).

Audio 4. Spotted Sandpiper Distraction Alarm Call. Credit: (Audubon).

Conservation Status

The Spotted Sandpiper’s population has had a decrease of nearly 50% since 1970. Despite this, they are classified as a species of Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (Wildlife Species Canada; IUCN). However, the Spotted Sandpipers cannot adapt forever and ongoing habitat degradation and climate change present potential future challenges for its population (Wildlife Species Canada; IUCN).

Interesting Tidbits

Spotted Sandpipers males are found to have high levels of the hormone prolactin compared to the females which is a hormone associated with parental care. (Reed et al. 2020)

Female Spotted Sandpipers have been found to have fewer, larger, and more irregular-shaped spots that cover a larger part of their bodies when compared to males (Blizard & Pruett-Jones, 2017).

Recent Research on the Spotted Sandpiper:

One of the most studied aspects of Spotted Sandpiper biology is its reverse sexual dimorphism and polyandrous mating system, which is rare in birds. Over the past 50 years, research has looked into the evolutionary, ecological and hormonal factors that drive this unusual reproductive strategy.

Recent research may be a bit of a stretch for the Spotted Sandpiper… unless you find the 1980s to still be considered recent. Regardless, these earlier studies have found fascinating insights into the Spotted Sandpiper’s unique polyandrous mating system and the influence of hormones on its parenting roles. Despite having limited new research, these foundational studies continue to help shape our understanding of the Spotted Sandpiper’s behaviour.

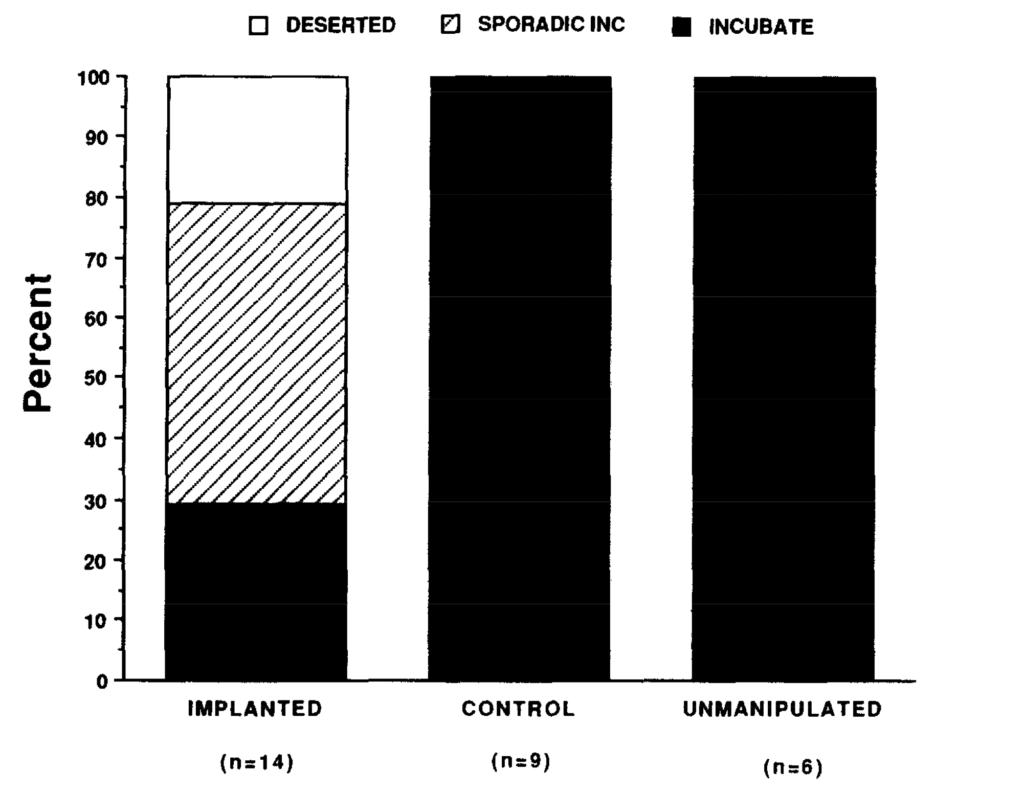

Male Spotted Sandpipers: High Testosterone, Low Patience

In a study done by Oring et al. (1989), researchers examined the influence of testosterone on the incubation behaviour of male Spotted Sandpipers. They used Silastic implants filled with testosterone to increase the hormone levels in incubating males to prebreeding-season levels. These implants created a hormonal state that naturally occurs before breeding and as a result, promotes sexual behaviour. They then observed the effects on incubation behaviour by comparing implanted males to control males, measuring differences in incubation constancy, nest desertion rates, and the frequency of courtship-related behaviours.

The study found that male Spotted Sandpipers with testosterone implants displayed significant variability in incubation behaviours. High testosterone levels resulted in a variety of responses: 20% of implanted males abandoned their nests, 50% reduced their incubation efforts, and 30% maintained normal incubation patterns (Oring et al. (1989)). Despite having high prolactin (the hormone associated with parental care), males with elevated testosterone often responded to females trying to court them by leaving their nests, revealing that testosterone increased sexual receptivity and as a result reduced consistent incubation. Their findings suggest that high testosterone reduces male incubation by increasing sexual receptivity instead of parental care.

Figure 4. High testosterone responses in implanted males, control males and unmanipulated males (Oring et al. (1989)).

This high amount of testosterone may also explain why the females lack a parental role, due to their natural testosterone levels being higher during incubation. It appears the more testosterone you have the worse of a babysitter you are.

Conclusion

The Spotted Sandpiper is not only a delightful species to observe, but it also provides fascinating insights into the complex world of avian biology. From its unusual polyandrous mating system to its long migration, the Spotted Sandpiper offers many research opportunities. Ongoing studies on this species’ reproductive strategies, habitat use, and physiological adaptations will continue to grow our understanding of its role in ecosystems and help to increase conservation efforts.

As climate change and habitat loss threaten many migratory bird species, including the Spotted Sandpiper, future research is going to be vital for ensuring the survival of not only this remarkable shorebird but many more.

Thank you for listening to my blog about the unique Spotted Sandpiper! If you have any questions please feel free to leave them in the comment section!

Figure 3. Drawing of The Spotted Sandpiper by Me! I’m no artist but thought I’d give it a shot!

References

Blizard, M. A. (2017). Dynamics of polyandry in spotted sandpipers (Actitis macularius): Ornamentation, reproductive success, and testosterone. The University of Chicago. https://knowledge.uchicago.edu/record/1345?ln=en&v=pdf

Blizard, M. A. & Pruett-Jones, S. (2017). Plumage pattern dimorphism in a shorebird exhibiting sex-role reversal (Actitis macularius). The Auk: Ornithological Advances, 134(2), 363-376. https://academic.oup.com/auk/article/134/2/363/5149181?login=false

Fivizzani, A. J. & Oring, L. W. (1986). Plasma steroid hormones in relation to behavioral sex role reversal in the Spotted Sandpiper, Actitis macularia. Biol. Reprod. 35:1195-1201. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3828434/

Government of Canada Wildlife Species. (2015). Spotted sandpiper(actitis macularius). Canada.ca. (n.d.). Retrieved from the Government of Canada website: https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/oiseau-bird-eng.aspx?sY=2019&sL=e&sM=a&sB=SPSA

Maxson, S. J., & Oring, L. W. (1980). Breeding season time and energy budgets of the polyandrous spotted sandpiper. Behaviour, 74(3-4), 200-263. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1981-27369-001

Oring, L. W., Fivizzani, A. J., & El Halawani, M. E. (1989). Testosterone-induced inhibition of incubation in the spotted sandpiper (Actitis mecularia). Hormones and Behavior, 23(3), 412-423. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0018506X89900536?via%3Dihub

Oring, L. W., Reed, J. M., Colwell, M. A., Lank, D. B., & Maxson, S. J. (1991). Factors regulating annual mating success and reproductive success in spotted sandpipers (Actitis macularia). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 28, 433-442. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00164125

Reed, J. M., L. W. Oring, and E. M. Gray (2020). Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/sposan/cur/introduction

Stone, W. (1925). Diving of the Spotted Sandpiper. The Auk, 42(4), 21. Diving Spotted Sandpiper

The Cornell lab of Ornithology. (2019) All About Birds: Spotted Sandpiper. Retrieved October 6, 2024, https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Spotted_Sandpiper/id#:~:text=In%20breeding%20season%20Spotted%20Sandpipers,the%20bill%20is%20pale%20yellow.

Willis, E. O. (1994). Are actitis sandpipers inverted flying fishes?. The Auk, 111(1), 26. Spotted Sandpiper Inverted Flying Fish?

Great post Emily! A really interesting read! I was especially intrigued by their teetering behaviour you mentioned and found some interesting info regarding it in this paper: Head Movement and Vision in Underwater-Feeding Birds of Stream, Lake, and Seashore by Lee W Casperson (https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=ece_fac).

The author makes the case that it seems there are some correlations between head-bobbing behaviour and birds who occupy aquatic niches/wading lifestyle strategies. What I thought was most interesting was the idea that birds might be doing this teetering-behaviour to better interpret what’s below the waters surface, such as the birds food source, by changing the refraction angle of light from the surface of the water. It would definitely make for a cool future study!

Also: amazing bird drawing, WOW!

Thank you so much for your kind words and for sharing that fascinating paper! I’m thrilled you enjoyed the post. The connection between their teetering and aquatic environment really does help to understand that behaviour and even more so it makes sense that adjusting angles for better visibility underwater would give them a practical advantage! The behaviour reminded me a bit about how some birds like seagulls do “rain” dances to cause worms to come up from the ground and it seems like this case is rather similar! Just an advantage to prey capture in a different environment! It’s definitely an idea I’d love to see explored further, as it opens up so many interesting questions about behavioural adaptation, and thank you for the compliment on the bird drawing; I had a lot of fun creating it!

First time hearing about prolactin! It’s fascinating that male SPSAs have more of this lactating hormone than females do. I wonder if this is consistent with other polyandrous species… anyways, thanks for the easy and informative read 🙂 and I love your drawing!

Hi Isabel!

Thank you so much for your comment! It is fascinating, isn’t it? Prolactin plays such a wide range of roles beyond lactation, especially in regulating parental behaviour.

As for other polyandrous species, that’s a great question! Similar patterns have been observed in quite a few species where males contribute significantly to offspring care, and is also present in a lot of mammals such as mice too! but it’s not universal. I’ve attached a paper that talks about it a bit but it’s really neat how it’s present in quite a few species!

And I’m so glad you liked the drawing! Thank you!

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.12.30.474525v1.full

Hey Emily,

Really great blog! I really loved the way you titled the current research, too funny. Also, it’s devastating to hear about how much populations of Spotted Sandpipers have declined, I’m wondering if you know if there are any current conservation efforts focusing on retaining or adding to the current populations?

Hi Ian, Thank you! The Spotted Sandpiper doesn’t appear to have any conservation efforts specifically focusing on this species due to it being classified as a “least concern” but The Canadian Shorebird Conservation Plan (CSCP) and the U.S. Shorebird Conservation Partnership work together to actually help protect healthy populations of shorebirds as well as their habitats! You can find more information on this site: http://nabci.net/foundation-for-conservation/bird-conservation-initiatives/shorebirds/#:~:text=The%20Canadian%20Shorebird%20Conservation%20Plan,and%20throughout%20their%20global%20range.

Thank you for reading my blog and leaving a comment!