Eric MacDowell

VIU Ornithology, Biol 325

Introduction

Imagine you are taking the coastal route home on a late November evening. The sun reaching towards the horizon with its golden hands until dusk arrives with a icy breeze. Suddenly, a bright flash of white and a whirlwind of movement in the sky catches your attention. You pull over and look up to see a dense cloud of hundreds of tiny birds all synchronously along the lagoon. You see a number of young adults bunched up in a tight group, all with binoculars up to their eyes. You call out to them, “What are these mesmerizing birds?”

“They’re Dunlins!” one of them shouted back, excitedly.

Taxonomy

Common name: Dunlin

Scientific name: Calidris alpina

Order Charadriiformes

Family Scolopacidae

Identification

The Dunlin is a stout, medium-sized migratory wading birds, commonly found flocking in large numbers in the fall. These birds are similar in size to many other of the sandpipers found across the pacific northwest at 16-22 cm long (Species showcase: Dunlin, 2024; All About Birds, 2024). An adult Dunlin comes in at a whopping 48-76 g, approximately the weight of a mole (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2024).

Identifying sandpipers can take some time, especially Dunlins. Characteristics that are found in Dunlins like black legs and a long, black, droopy bill that resembles pencil may lead you to think of the Western Sandpiper (Ehrlich, Dobkin, Wheye,1988; All About Birds, 2024). However, Dunlins have darker shades of plumage and are larger size which are small details that may help guide you to identifying Dunlins (Ehrlich, Dobkin, Wheye,1988).

During breeding season (spring and summer), these cute sandpipers are easy to spot due to a few characteristic features. Their mottled chestnut brown and black backs, along with copper-coloured caps, are typical of their breeding plumage. Additionally, both male and female Dunlins have black belly patches surrounded by white feathers, which are iconic to their breeding appearance (All About Birds, 2024).

Dunlin non-breeding plumage is less striking compared to their breeding plumage. In fact, the name Dunlin originated from the an early English word, “dunling,” which means “little brown one” as reference to the colour of their non-breeding plumage which is quite muted grayish brown, also known as “dun.” (All About Birds 2024).

Males and females can be quite difficult to differentiate at this time because both sexes have very similar appearances (Malick-Wahls et al., 2024). However, females tend to be larger in size with slightly longer bills (Malick-Wahls et al 2024; eBird, 2024). Breeding plumage may give a better idea between the two where males generally have whiter or lighter hindnecks but this difference is not always present (Malick-Wahls et al., 2024).

Another distinguishing feature, visible in all plumage types and sexes, is the white underwings which are distinctive in flight. (All about Birds, 2024). It’s truly incredible to see a large flock in flight, with the bright flashes of their underwings as they wheel around the bay.

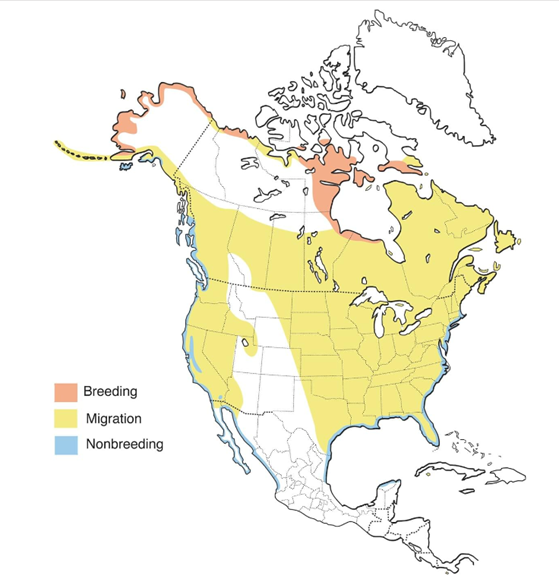

Habitat, Migration

Since there are six known genera of dunlin and many of them have different migration pattens, I will focus on the North American populations of Dunlin in the genus, Calidris alpina (Environment Canada, 1997). These sandpipers breed in subarctic and mid arctic wetlands during the spring and summer but may use sandy beaches, coastal grasslands, and muddy freshwater areas if the preferred environment is not available (Environment Canada, 1997). By late summer and early fall, breeding has finished, and dunlins stock up on food then independently disperse as juveniles to a large range of locations on the North American coastline (All about Birds, 2024). Interestingly, they tend to stay at higher latitudes when migrating much later in the fall than most shorebirds (Environment Canada, 1997). Wintering locations can vary from as north as the coast of British Columbia and New England to as far south as the Northern Mexico and Florida (All about Birds, 2024). Wintering locations can also change based on a number of factors such as food availability and predators (Environment Canada, 1997). In regard to habitat type during the winter, Dunlins prefer environments such as coastal estuaries, muddy intertidal zones , agricultural lands (Martins, Santos, Palmeirim, Granadeiro, 2013).

Food and Behaviour

While migrating or during their non-breeding season (winter), Dunlins heavily rely on the intertidal zone for food. You may see them getting chased by the tide, running back and forth around low tide feeding areas, probing the mud and sand with their long, curved bill (Koloski, Coulson, Nol, 2016). During the wintering period, their diet consists of organisms such as crustaceans (and their eggs!), mollusks, insects, and marine worms (Canadian Wildlife Service, 2014). In contrast, during breeding season, they feed primarily on flies and mosquito larvae (Canadian Wildlife Service, 2014).

Murmuration

Dunlins are exceptional at flying within a flock. At dusk and while nesting, tight and cohesive flying with up to 500 individuals without a leader helps provide safety in numbers against predators such as the Peregrine falcons, increases and creates a mesmerizing birding experience (Ruiz, Connors, Griffin, Pitelka, 1989; All about Birds, 2024; American Bird Conservancy, 2017). This behaviour is also exhibited in starlings and is called murmuration (Ruiz, Connors, Griffin, Pitelka, 1989; All about Birds, 2024).

Reproduction

Dunlins are a bit quirky; they don’t attempt second broods if the first one fails nor do they breed in their first year of life. Most Dunlins actually breed in their second (Environment Canada, 1997). Since they are such an aggregate species in their non-breeding season, it can be unexpected for non-birders when learning they are quite territorial, monogamous, and nongregarious during breeding season (Environment Canada, 1997). Dunlins breeding seasons look a little different than a similar looking sandpiper species called the Western Sandpiper (All About Birds, 2024). Instead of females choosing the nest site, males tend to arrive first (Environment Canada, 1997). They decide where to place their nests and begin creating it (Environment Canada, 1997). Nest building begins with the males in hidden grassy areas, in which they dig a depression, also known as scrapes (Environment Canada, 1997). Then, grasses and leaves are spread along the scrape. Afterwards, females will choose which nest they prefer once they arrive and finish building it (Environment Canada, 1997). To attract females, males must use courtship to win them over (Environment Canada, 1997). This includes flying in a short gliding fashion with arched wings, and rapid fluttering (Environment Canada, 1997). Once a male is chosen and eggs are laid, incubation usually lasts just under a month at approximately 20 days. Afterwards, both parents tend to young, but the female tends to leave after the first week following hatching. The male will stay until young reach fledging, nearing the end of the 20 days period (Environment Canada, 1997).

Conservation

Population trends have been on the decline since 1970, but in 2015, there were population estimates of over 1,000,000 adult dunlins breeding or migrating within Canda(American Bird Conservancy, 2017). In 2018, population numbers indicated to the IUCN the Dunlin is a species of low/least conservation concern (Canadian Wildlife Service, 2014). However, a pattern of destruction of habitat in migration and wintering grounds have been identified and in recent years, Dunlins has become a focus for conservation and stewardship (American Bird Conservancy, 2017).

Fun facts

- In 1931, a British Ornithologist named Edmund Selous was so amazed by how synchronous Dunlin flock movement that he speculated that telepathy must be involved (Davis,1980)

- A group of dunlins are collectively known as a ‘flight’, ‘fling’, and ‘trip’ of Dunlins (Reurink, Hentze, Rourke, Ydenberg, 2016).

- Dunlin flocks flight speed can reach up to 25 meter per second or 90 kilometers per hour (Reurink, Hentze, Rourke, Ydenberg, 2016).

- Dunlins may pair up for breeding before reaching breeding grounds due to weather (Environment Canada, 1997).

Current Research:

The abundance of small mammals is positively linked to survival from nest depredation but negatively linked to local recruitment of a ground nesting precocial bird

Dunlins are small and are ground nesting birds. One question I had was: what is a possible factor that that could have a role in nest depredation? A group of researchers in Finland were able to answer this question investigating predator-prey relationships (Pakanen et al., 2022). According to the alternative prey hypothesis, predators will switch to a different prey species if their primary prey species’ population has declined. Generalist predators generally prey on small mammals, but studies suggest that they will turn to bird nests when small mammals are scarce. Furthermore, they can identify and learn how to use the most beneficial and abundant prey source quickly. A study was done on a breeding dunlin population on the coastal meadows in Finland from late April to July to study nest depredation in the absence of natural mesopredator prey (small mammals) population sizes (Pakanen et al., 2022). They trapped these small mammals in their common habitats to see if it caused nest depredation by bird predators like Marsh harriers and mammalian predators such as red foxes.

Based on a combination of results and previously collected small mammal data, it was discovered spring and fall abundance of small mammals were negatively linked to dunlin nest depredation (Pakanen et al., 2022). This type of research is critical in understanding generalist predators and how interconnected and sensitive these environments are. With climate change and invasive species, this could become an imminent threat to small, ground nesting birds.

References:

American Bird Conservancy. (2017). Dunlin. https://abcbirds.org/bird/dunlin/#:~:text=A%20group%20of%20Dunlin%20are,predators%20are%20an%20impressive%20sight

Canadian Wildlife Service. (2014). Dunlin (Calidris alpina) – Bird status report. Government of Canada. https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/oiseau-bird-eng.aspx?sY=2014&sL=e&sM=p1&sB=DUNL

Davis, J. M. (1980). The coordinated aerobatics of dunlin flocks. Animal Behaviour, 28(3), 668-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(80)80127-8

“Dunlin Life history, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.” (accessed October 2024) Www.allaboutbirds.org, https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Dunlin/lifehistory

eBird. Dunlin. (accessed November 1, 2024). https://ebird.org/species/dunlin

Ehrlich, P., D.S. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. (1988). The Birders Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds. Simon & Schuster Inc., New York. 785 p.

Koloski, L., Coulson, S., & Nol, E. (2016). Sex determination in breeding dunlin (calidris alpina hudsonia). Waterbirds (De Leon Springs, Fla.), 39(1), 27-33. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.039.0104

Malick-Wahls, S., Byrkjedal, I., Ganter, B., Lifjeld, J. T., Marthinsen, G., Roesner, H., & Lislevand, T. (2024). Morphometric differences between sexes and populations in norwegian dunlins calidris alpina. Bird Study, , 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2024.2392214

Martins, R. C., Catry, T., Santos, C. D., Palmeirim, J. M., & Granadeiro, J. P. (2013). Seasonal variations in the diet and foraging behaviour of dunlins calidris alpina in a south european estuary: Improved feeding conditions for northward migrants. PloS One, 8(12), e81174-e81174. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081174

Pakanen, V., Tornberg, R., Airaksinen, E., Rönkä, N., & Koivula, K. (2022). The abundance of small mammals is positively linked to survival from nest depredation but negatively linked to local recruitment of a ground nesting precocial bird. Ecology and Evolution, 12(9), e9292-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9292

Reurink, F., Hentze, N., Rourke, J., & Ydenberg, R. (2016). Site-specific flight speeds of nonbreeding pacific dunlins as a measure of the quality of a foraging habitat. Behavioral Ecology, 27(3), 803-809. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arv223

Ruiz, G. M., Connors, P. G., Griffin, S. E., & Pitelka, F. A. (1989). Structure of a wintering dunlin population. The Condor (Los Angeles, Calif.), 91(3), 562-570. https://doi.org/10.2307/1368106

Species showcase: Dunlin: IUCN UK Peatland Programme. IUCN Peatland Programme. (2024). https://www.iucn-uk-peatlandprogramme.org/biodiversity/species-showcase-dunlin

Great blog Eric! I especially liked the visual hook at the beginning! I was wondering if Dunlins have ever been seen to form mixed flock murmurations with other shorebird or other species, or if they tend to keep to their own species?

Thank you for the comment, Bekah!

I have not witnessed multiple species murmuration nor have I seen any articles on this so this leads me to believe they tend to stay with their own species. However, I would think there could be cases of of this with other small shorebirds due to different diets and less threat of predation

Very interesting blog, Eric! Such a fascinating little bird, it’s sad to hear about the threats they’re facing with damage to migratory routes and wintering grounds. I was wondering what kind of ecological roles they play in those intertidal areas, and how their decline would impact other species? I would assume they are an important prey species, especially when gathered in large groups in the non-breeding season.

Hi Eric,

I appreciate your attention to detail when discussing the identification of Dunlins. It’s interesting to read about them in comparison to my blog species, the western sandpiper because while they look very similar, they have so many features and behaviours that distinguish them.

Do you know if they use any vocalizations along with wing flapping during courtship?

Wow Eric!

I had no idea that Dunlins flew with such speed! 90 kmph is crazy, especially in groups of 500. I know that you mentioned that they migrate to a wide array of different areas, and how it depends on available resources, but I was wondering if you know how they determine what area is the best bet, or if the hedge their bets based on the climate of the past breeding season?