Equipped with pointy horns, this little devil can be found throughout North America. Being the only native lark to this continent, they sure are a sight to behold.

Identification

Common name: Horned Lark

Scientific name: Eremophila alpestris

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Alaudidae

In their adult breeding plumage, males have a white belly, dusty brown back, a yellow throat, black mask, and distinct black horns. These horns are made up of a few feathers that are generally only upright in males. Females are generally more of a brown-grey colour, and lack a black mask. Adult individuals are about the size of a robin with a total length of 18-20cm.

Vocalizations of the Horned Lark vary from very long and complex songs, to short calls. Long songs are usually produced by the males during breeding season where they become more frequent and very loud, males also let out an extremely loud “challenge call” when defending territory. The challenge call is followed by a random assortment of notes when males go into battle. Both females and males produce alarm calls that are similar to the challenge call but much softer (Beason & Franks, 1974).

Short song – In flight Credit: (Audubon)

Long song – In flight Credit: (Audubon)

Calls Credit: (Audubon)

Call Credit: (Audubon)

The video link is the Horned Lark in action! Take a peek. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xpImtdMbZs8

Habitat and Diet

As we will later discuss, there are 20 plus subspecies that have different habitat preferences but all rely on the same diet. Usually, when feeding, the Horned Lark can be seen running or walking across large open areas with their mate, usually human made fields in the low-lands. The adults forage for seeds and seedlings in the non-breeding season, but shift their focus towards a more insectivore type diet one they have their young.

These large open ares are either sparse, high-elevation alpine areas, or open fields and meadows. In the case for alpine populations that migrate to low-lands for the winter, populations gain higher sightings around heavily grazed farm fields. So if you are dead set on spotting Canada’s only Indigenous Lark, loiter around your nearest farm in the winter months!

Out of the >20 breeding subspecies in North America, the following are three of interest:

- E. a. arcticola “the Pallid Horned Lark” tends to occur in high elevation areas. These places usually have sparse forests and little protection by trees, expansive rocky or grassy areas, and in some extreme cases rocky tundra with little to no plant life at all (BirdAtlasBC).

- E. a. merrillii “the Dusky Horned Lark” breeds in lower elevations than E. a. arcticola, and prefers grasslands that are more inland. Finding these populations means that you have to find large meadows or inland human made fields (BirdAtlasBC).

- Sadly, the last subspecies on this list extricated (no longer exists in Canada but could occur elsewhere). E. a. strigata “the Streaked Horned Lark” preferred coastal areas along the Pacific Northwest. In breeding season it could be seen in estuaries and grasslands all along the Pacific North American coastline. Unfortunately the last sighting of this subspecies breeding in Canada was in 1978. Populations of the Streaked Horned Lark still exist in the United States while also classified as threatened (Adrian et al. 2020).

Nesting and Behaviour

As expected, Horned Larks make their home on the ground. In those same grassy meadows (or snowy tundra), they make small, finely woven nests out of fine grass materials. At the beginning of the April breeding season, females choose a nesting site which has at least one larger, conspicuous, object next to it. This can be anything from a large rock, to a taller patch of grass. With no help from her mate, she digs into the ground enough so that the top of her nest is just below the to of the ground. After painstakingly weaving her nest, she lines it with insulating materials like tufts of animal fur, or fluffy plant materials (AllAboutBirds).

All while the female Horned Lark is spending her time making a suitable nursery for her young, the males ferociously defend their territory. They can be seeing flying high in the sky scratching each other the whole way down, or battling each other on the ground.

Though clutch size can vary among sub-species, each female has an average of 2-5 young. Interestingly enough E. a. arcticola populations have a higher survival rate even though the breeding season in alpine areas are so much shorter. It was found that species that breed in the low-lands face more habitat destruction and higher predation rates, even though their breeding season is longer, less of their young are expected to reproduce(Canfield et al. 2010).

Range and Migration

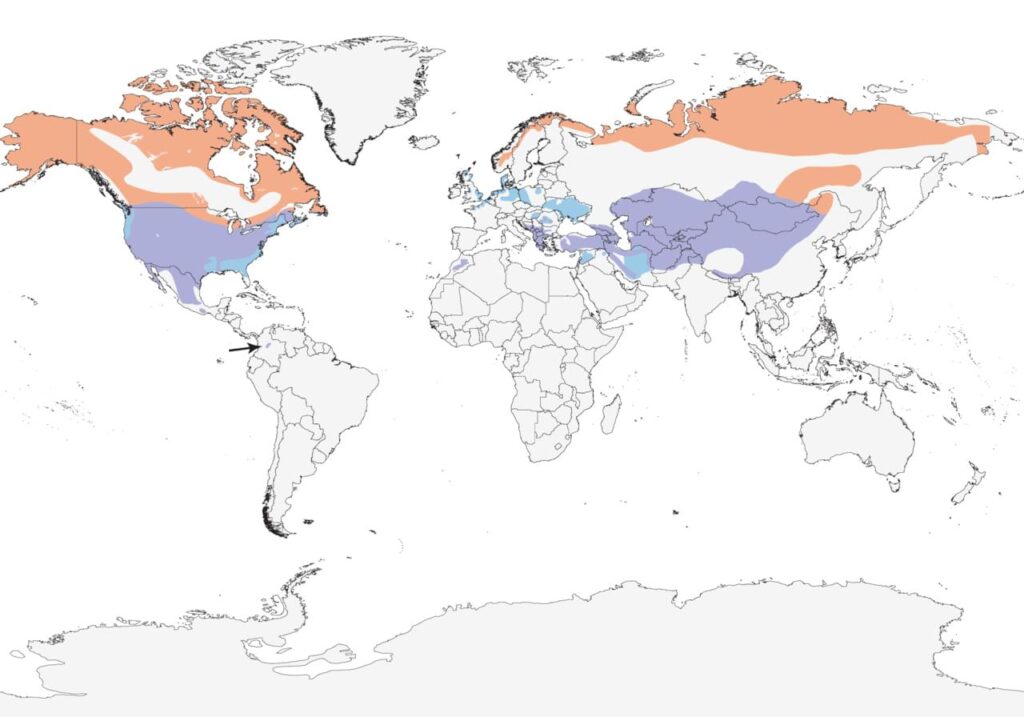

Horned Larks can be found throughout the northern hemisphere and undergo short-range migrations. For populations that breed in northern tundra habitats, they move down below the 48th parallel for the winter months (BirdsoftheWorld). For sub-species that breed in alpine areas, an even shorter migration occurs, they just move down to the lower land areas until alpine areas return to the suitable breeding temperature. The image above shows the average range of all subspecies with the orange showing breeding range, purple is year-round range, and the blue is the non-breeding range.

On the topic of conservation, because the populations are so wide-spread, full scale conservation efforts have not been employed. Overall Horned Larks experience a 2% population decline each year, with some subspecies like the Streaked Horned Lark being extirpated from Canada completely. Most of this decline can be related to reforestation of agricultural lands, encroachment of urban landscapes on meadows, and higher predation rates closer to urban areas (Camfield et al, 2010).

Recent Research

As we know, development of suitable habitat is one of the main causes of Horned Lark population declines globally. However recent research has shown that reclamation of former breeding and non-breeding habitats results in a positive increase in Horned Lark populations returning. In 2022 a paper published by Ingvar Byrkjedal and Göran Högstedt focused on surveying Horned Lark territories at two sites in Sweden (Byrkjedal & Högstedt, 2022).

The subspecies they surveyed was Eremophila alpestris that breed at high elevations and migrate to the low-lands for the winter. Historically, large populations used these breeding grounds routinely, but mid way through the 20th century, populations started to decline. However, through other ground surveys in the late 70’s, Horned Larks were reported to be calling while flying overhead. This sparked a long term study into recording the return of Horned Larks to the Hardangervidda and Varanger study areas.

Results

From 1979-2021 there was a steady increase of Horned Larks territories at Hardangervidda. From 1979-1985 average territories were 4.8. Then, from 2004-2021 average territories skyrocketed to 13.3. Nesting densities (breeding pairs) saw a similar increase from 0.4-1.0 pairs/ Km2 in the first interval to 1.4-2.9 pairs/ Km2 in the second interval.

This massive increase is thought to be a result of the reclamation and conservation of the winter low-land habitat. In this case, the winter habitats existed on the coastline of the North Sea. From 1950-1980 construction was constant along the coastlines to prevent flooding, this caused huge disturbances, declines in viable habitat, and food shortages. After construction was completed, conservation measures were taken to restore the coastal salt marshes and meadows, resulting in the return of shrubs and grasses. Shortly after, Horned Larks started to return.

This research shows us that multiple steps need to be taken in order to see positive change, efforts need to be taken to survey local breeding grounds and non-breeding habitats before they are disturbed. Something as simple as protecting one area of shoreline can impact entire population sizes.

Now go and stalk the nearest farm land or just sit on your airport’s tarmac. Support your local larks!

Thanks for reading.

References

Beason, R. C., & Franks, E. C. (1974). Breeding Behavior of the Horned Lark. The Auk, 91(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/4084662

Byrkjedal, I., & Högstedt, G. (2022). Numbers of Horned Lark (Eremophila alpestris) are increasing at high alpine and arctic breeding sites in Norway. Ornis Norvegica, 45, 10–15. https://doi.org/10.15845/on.v45i0.3640

Camfield, A. F., Pearson, S. F., & Martin, K. (2010). Life history variation between high and low elevation subspecies of horned larks Eremophila spp . Journal of Avian Biology, 41(3), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-048X.2009.04816.x

Hartman, C. A., & Oring, L. W. (2003). Orientation and Microclimate of Horned Lark Nests: The Importance of Shade. The Condor, 105(1), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/condor/105.1.158

Mahoney, A., & Chalfoun, A. D. (2016). Reproductive success of Horned Lark and McCown’s Longspur in relation to wind energy infrastructure. The Condor, 118(2), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-15-25.1

Wolf, A. L., Slater, G. L., Pearson, S. F., Anderson, H. E., & Moore, R. (2020). Range-Wide Patterns of Natal and Breeding Dispersal in the Streaked Horned Lark. Northwest Science, 94(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3955/046.094.0103

Awesome blog Ian!