Common name: Vaux’s swift

Scientific name: Chaetura vauxi

Order: Apodiformes

Family: Apodidae

Dear Reader,

Hang onto your pantaloons as I take you through yet another of my bird-watching experiences. Your challenge while reading this article is to suspend your disbelief for five minutes and imagine yourself in an alternate world where birds can talk and possess an incredible degree of self-awareness.

Ready? Okay, I’ll set the scene.

It was a beautiful evening in late April. I had driven a few hours north along highway 19 from my home in Nanaimo to the Courtenay & District museum; a beautiful brick building known to temporarily house a particularly interesting bird called the Vaux’s swift (pronounced “Vawks”).

Driving into the parking lot at 20:00, I could see that there were already 15-20 people in various stages of preparedness with their lawn chairs, spotting scopes, binoculars, and blankets. Some were already watching the sky for the greatly-anticipated moment where, as I had been informed, hundreds of Vaux’s swifts would flock together before rapidly funnelling into the museum’s brick chimney.

So many questions rattled through my brain as I stood among the crowd. Why do these birds do this? Why come here to this museum specifically? How many of these birds could possibly fit in there? What even is a Vaux’s swift?

I knew the only creature that could give me the answers I was looking for were the Vaux’s swifts themselves. During the frustrating minutes I spent preparing my recorder and tiny microphone, I must have caught the eye of a rather empathetic swift of whom swooped down beside my chair. Clinging onto the deep furrows of a Douglas Fir, this swift seemed keen enough to give me a few minutes of their time.

Introduction and Identification

Oh, hello there. I was really hoping to talk to one of you tonight, so thank you for coming down to speak with me!

Do you have an individual name or do you just go by Vaux’s swift? That must get confusing – considering there are so many of you.

Hah! That’s a funny question but I’m grateful you asked. We do all have individual names. Mine is **vocalization** – which I do not expect you to know how to pronounce. We are collectively named after the American scientist William Sansom Vaux. As you may have heard, we’re likely to be swept up in the long list of birds who will have their eponymous English names replaced in favour of something more descriptive. I’m looking forward to seeing what the American Ornithilogical Society comes up with.

I’m sure some of our readers are familiar with your species, but there are many of us who are brand new to birding, ornithology, bird-watching…whatever you want to call it. How would someone be able to tell you apart from say, a swallow, another kind of swift, or any other small-to-medium sized bird?

A good place to start is by giving your readers some key identifying features so they can spot us if we happen to pass through their area.

Okay so what do we look like? Well, we are the smallest of the North American swifts coming in at only 11 cm long with a 28 cm wingspan and weighing anywhere between 15-22 grams. Think of somewhere between a sparrow and a robin (All About Birds).

If you look up and see an overall brownish, tube-shaped body with a relatively paler chest and long crescent or boomerang-shaped wings, you may be looking at one of us.

I’ve been told we have “cigar-shaped” bodies, but I really resent that comparison even if it is annoyingly accurate. By the way, all of these descriptions apply to both the male and female sexes, though us males average slightly heavier than our female counterparts.

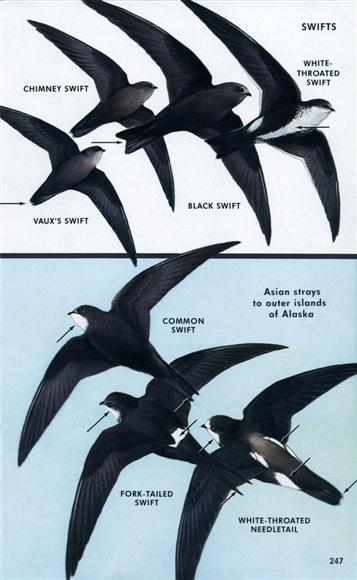

Other species that you may confuse us for are the Black swift and the Chimney swift. Both are quite a bit larger and neither have pale brown/gray plumage on their throat, chest, or uppertail (All About Birds).

Top panel:

(Left to right) Vaux’s swift, Chimney swift, Black swift, White-throated swift.

Bottom panel:

(Top to bottom) Common swift, Fork-tailed swift, White-throated needletail

Credit: Peterson Field Guide to birds of Western North America

Distribution

Now, you mentioned “passing through”… could you describe where you are native to and where you would be travelling to/from?

I say “passing through” because we are currently going along our long-distance migration route from our overwintering grounds in Central and South America to our North American breeding grounds. We have confirmed nesting sites as far north as the Stikine River drainage in northwestern British Columbia all the way south through the coastal and central California mountains (BC Bird Atlas). Hence why we’re referred to as the “migratory population”, whereas the resident “Richmond’s” swift inhabits large areas of Mexico and Central America year-round. The resident Richmond’s swift have relatively darker plumage overall with a paler throat and browner rump (eBird).

Habitat and Behaviour

I’ve discussed a bit with my readers previously about the concept of “guilds” or groupings of species that exploit the same class of environmental resources in a similar way. Can you talk a bit about what guild you belong to?

Well, I’m an aerial insectivore meaning I am a flying, fly-eating animal. Well, not just flies but you know what I mean. We are exceedingly adept at foraging during flight via rapid pursuit, but can also glean a tasty insect off of a tree branch if the opportunity presents itself. Honestly, I’m a pretty picky eater. I never could get myself to eat booklice, but my friends and family are known to eat hoverflies, ants, aphids, lanternflies, spindlebugs, bark beetles, moths, bees, leafhoppers…you name it (All About Birds).

As my uncle used to say “if it flies, it dies”.

What a great catchphrase.

So, the big question remains – What is it about this chimney in particular that is so appealing to you all as a communal roosting site?

There’s just something about an old chimney. Unlike the majority of other passerines who have anisodactyl feet made for perching, ours are known as pamprodactyl feet – where the first and fourth digits can be moved from the back to the front so that all toes are facing forward. This kind of toe arrangement makes us uniquely suited for clinging to vertical surfaces, where our tails can be used as a sort of “kick stand” (All About Birds).

Anisodactyl foot.

Credit: Kidwings

Credit: Kidwings

The more modern chimneys have that awful wrapping on the inside of them, covering the edges that we need to cling onto when roosting. It’s really hard for us to understand why so many of the older chimneys are being capped or traded in for newer models when there is such limited availability of suitable nesting and roosting habitat.

Historically we had been choosing late-seral stage forests for nesting and roosting, as they would tend to have trees with suitably-sized woodpecker cavities and/or large, hollow trees such as the Western Redcedar (BC Bird Atlas). In the absence of those types of mature to old-growth mixed forests, a brick chimney may be the best we’ve got. Once those are gone…sheesh, I’m not sure what we’ll do. Luckily we have people on the ground such as our friends at Vaux’s Happening, who are focused on promoting the conservation of migrating Vaux’s swifts by highlighting roosting events such as this one.

I know this may be a bit embarrassing, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask you the ~spicier~ question that I know my readers are dying to know about.

Can you tell us about your breeding behaviour?

I have to say, we exhibit fascinating breeding behaviours. We arrive at nesting sites in small, vocal groups and quickly form pairs, often reuniting with previous mates. Interestingly, a third swift may occasionally join in our courtship flights, though the reason for this behaviour is not well understood. It gets a bit weird sometimes, actually…

Mating occurs in mid-air, with the male riding on the female’s back for a brief period as she glides. Unlike many bird species, we do not establish territories; multiple pairs can nest peacefully in the same tree, and non-breeding birds often roost in the nesting cavities alongside them (All About Birds).

Wow, come to think of it, we’re just a bunch of hippies.

I understand that your nestlings are altricial, meaning they are born underdeveloped. Although I don’t have any children of my own, I can appreciate the parental aid required up until those little helpless buggers attain self-sufficiency. What is parenting like for you all?

We can have clutch sizes anywhere from 3-7 eggs, and both parents help with incubating. We also both share in the responsibility of keeping our hatchlings fed and sometimes a third, non-related adult will help. It’s kind of nice to have a non-related bird help raise our young considering we make roughly 50 trips to the nest per day to regurgitate a bolus of over 100 insects each visit (All About Birds).

You know what they say – it takes a village to raise altricial hatchlings.

Credit: Charles T. Collins

Note: This is a photo of an adult White-throated swift carrying a bolus of nestling food. There are no photos of Vaux’s swifts doing this!

And your nests? What are those like?

Both Mom and Dad help build the nest. We use our own saliva and whatever small twigs we can find to adhere to the side of hollowed-out trees. As I previously mentioned, we like large-diameter cavities in old growth trees for nesting, but some of our friends down in Oregon have taken to accepting artificial nest boxes where we have historically nested as well as in habitats that lack natural nest sites (Bull, 2002).

Recent Research

I want to shift gears and ask you some harder-hitting questions…

How is your guild doing in terms of population numbers?

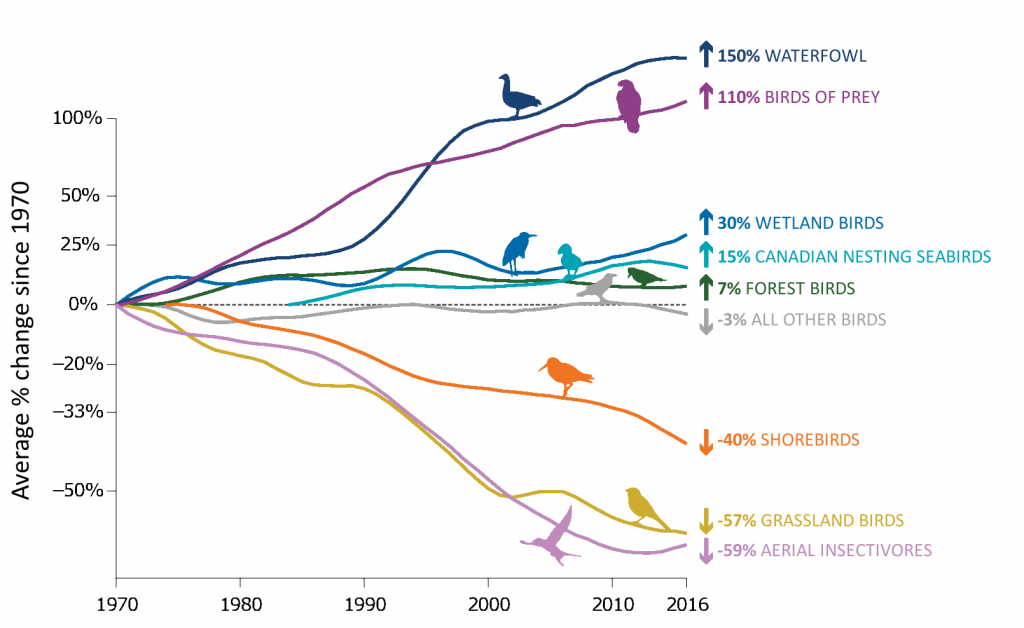

Unfortunately, our guild has experienced significant population declines. As per a report published in 2019, populations of aerial insectivores have declined by a whopping 59% over the last fifty years (NABCI).

It seems like it should be a simple linear relationship, doesn’t it? Less insects equals less insect-eating birds. While it is true that declines in aerial insectivore populations are linked to changes in populations of flying insects, these changes are likely indicative of underlying ecosystem changes (Nebel et al., 2010).

Not to be too dramatic, but our decline is more like a “death by a thousand cuts”. We are, afterall, a complex and diverse guild and as such it stands to reason that there are similarly complex and broader ecological reasons for the decline in both insect and aerial insectivore populations. Some of those reasons are more straightforward, like pesticide use for instance! While things like phenological changes due to a warming climate are a bit more difficult to fully understand. There are so many other factors contributing to our decline; direct or indirect impacts of environmental contaminants, habitat loss, and conditions on migratory stopover or wintering grounds to name a few (Spiller & Dettmers, 2019).

We can’t really talk about migration without talking about climate change. Have the shifts in ecosystems and weather systems as a result of climate change affected your migration timing?

Shifts in ecosystems and weather systems due to climate change have definitely impacted our migration timing. We rely on specific environmental cues, such as temperature and the availability of food sources, for timing our departure and arrival to and from our breeding grounds. As climate change alters weather patterns, the timing of seasonal events—like the emergence of insects, which are crucial for feeding the swifts—can become mismatched. For instance, if warmer temperatures cause insects to hatch earlier, swifts arriving later may find less food available. Additionally, changes in precipitation patterns can affect nesting sites and habitat quality, further complicating our migration timing.

The big question then is, have we noticeably shifted our migration timing in recent years?

A study by Prytula et al., looked at community science data from eBird spanning from 2009–2018 to try and answer that very question. They found that our migratory population displayed an advance in the start of spring migration and a delay in the end of fall migration – possibly as a response to an earlier arrival of spring and a potential delay in the colder temperatures typically associated with the onset of fall.

To be exact, the start of spring migration advanced by 1.4 days/year, and the end of fall migration was delayed by 1.6 days/year between 2009-2018 (Prytula et al., 2023).

Coming back to the insects… has there been any recent research on their abundance or diversity that has piqued your interest?

A study by Pomfret et al., looked at whether there was a link between population declines in Vaux’s swifts and a reduction in their diet quality. They first collected a vertical core sample from a guano deposit in a chimney on Vancouver Island, BC, Canada. Afterwards, they analyzed the egested arthropod exoskeletons, identified them by order and measured stable nitrogen isotope (δl5N) signatures at each layer.

What their 26-year dataset revealed was incredibly fascinating. There was an increase in the ratio of Hemiptera to Coleoptera. Why is this important? Hemipterans typically occupy a higher trophic level than Coleopterans but offer less caloric value per individual. Also, that stable isotope, δl5N, showed a significant negative correlation with an annual population index from the Breeding Bird Survey.

It’s possible then, that diet quality may be contributing to the decline of Vaux’s swift populations, and that this issue may also affect other aerial insectivores (Pomfret et al., 2014).

I wish we could end on a more positive note, but I really wish you all the best. Good luck!

Wow, I really must be going. I think everyone is already in the chimney! Goodbye!!!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Well dear reader, that was an interview with a Vaux’s swift. I hope you were able to use your imagination, and learned a thing or two about our little friend.

Lastly, leave a suggestion for what you think the Vaux’s swift should be renamed as!

References

- Bull, E. L. (2002). Use of nest boxes by Vaux’s Swifts. Journal of Field Ornithology, 74(4), 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1648/0273-8570-74.4.394

- Nebel, S., Mills, A., McCracken, J. D., & Taylor, P. D. (2010). Declines of aerial insectivores in North America follow a geographic gradient. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ace-00391-050201

- Pomfret, J. K., Nocera, J. J., Kyser, T. K., & Reudink, M. W. (2014). Linking population declines with diet quality in Vaux’s Swifts. Northwest Science, 88(4), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.3955/046.088.0405

- Prytula, E., Reudink, M., LaZerte, S., Sonnleitner, J., & McKellar, A. (2023). Shifts in breeding distribution, migration timing, and migration routes of two North American swift species. Journal of Field Ornithology, 94(3). https://doi.org/10.5751/jfo-00341-940314

- Spiller, K. J., & Dettmers, R. (2019). Evidence for multiple drivers of aerial insectivore declines in North America. The Condor, 121(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/condor/duz010

What a great creative format to your blog article Alysia! I loved reading it and laughed a few of the jokes. I have never seen a Vaux’s Swift but I have heard of the flock at the Courtney museum. They are definitely on my life list as a local species I need to see! I really appreciated you highlighting the decline in areal insectivores in particular. I want to know, besides climate change, what do you think is causing a shift in the Vaux’s swifts migration delay?

I think a good name for the rename should be Grey Swift!

Thank you for reading and laughing along, Chelsey!

If you get the chance to, I would HIGHLY recommend going to the Courtenay museum during peak spring migration; it’s definitely a sight to behold.

Sorry ahead of time for this reply; it’s very “stream of consciousness”.

The tricky part of defining issues outside of climate change (CC) in relation to migration timing is that climate change an all encompassing threat that has cascading effects. To try and distinguish between what can be attributed to CC or not with respect to migration delays is difficult to accomplish.

For example, Vaux’s swifts could be tracking earlier spring phenology (think: earlier plant and insect emergence during this time) to be in time with a boom in primary productivity at their major stop overs and breeding grounds. This can be related back to temperature regimes that can then be attributed to CC. You can do this for a lot of arguments as to why lots of birds are advancing and/or delaying their migration windows.

Okay, so what can I think of that would be outside of the large umbrella that is CC…

Atmospheric pressure? Nope, influenced by CC.

Maybe habitat alteration at critical stop over locations. That could be one! Habitat loss or conversion could change resource availability or even cause changes to migration routes. That could cause a delay in fall migration!

Hope this was helpful?

Thanks again!!

P.S., I love the proposed name 🙂

Thank you for covering the hard hitting questions I didn’t know I needed to hear! Loved this interview and learned a lot. Thanks for sharing!