Photo from Ducks Unlimited https://www.ducks.ca/species/ruddy-duck

Part I – General Information and ID

Description and ID

The Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis) is a small species of diving duck belonging to the Anatidae family in the order Anseriformes. Learning to identify waterfowl can be a dubious task but there are certain traits that can help in the case of the Ruddy Duck.

- Size

- Does it dive or dabble?

- Can you see its tail?

- Is it sleepy?

Ruddys are quite small at 300-850 grams compared to the well-known Mallard’s hefty 1000-1300 grams (All About Birds Ruddy Duck; All About Birds Mallard). Still, Ruddy ducks have been described as “very chunky” which may explain their nickname “butterball” (Johnsgard 2010 pp. 530, 529). They are stocky, with a small frame and a thick neck. Without a direct comparison it can be difficult to tell the size of a bird, so instead, look at its behaviour; does it dive or dabble? Ruddy Ducks dive fully underwater to find their meals while dabbling ducks, like Mallards, tip upside-down, keeping their back half above the water to eat. So, if you see a duck butt sticking up in the air, it most likely does not belong to a Ruddy duck.

NOT a Ruddy Duck

Photo of a dabbling Mallard by Emma Wallace-Tarry

The plumage of a Ruddy Duck is not a super helpful identifier during much of the year, as males and females maintain a drab grayish-brown coat through fall, winter, and early spring. If you see a small, diving duck with indistinct plumage, try looking at the tail. If it has a distinct stiff-looking tail pointing up or sitting flat on the surface of the water, you are looking at a stiff-tailed duck; if you are in Canada, it is almost certainly a Ruddy. There are eight other species of stiff-tailed duck in the world. Still, Ruddy Ducks are one of only two species in North America, the other being the Masked duck (Oxyura dominica), which only travels as far north as Texas (Johnsgard 2010).

These inconspicuous ducks are typically silent and often “lethargic” (Audubon). Ruddy Ducks are more active at night and are often observed sleeping during the day. This might make it hard to use the other identifying behaviours, but if you see a really sleepy duck, it’s worth considering that it’s a Ruddy.

Plumage

The distinguished male breeding plumage is only present in late spring and summer (Johnsgard 2010). Otherwise, look for the clear white cheek patch in the non-breeding male, which is streaked with brown in females. Telling apart immature males from females is left to the experts…

Breeding male

Non-breeding male

Female/Immature male

Habitat and Range

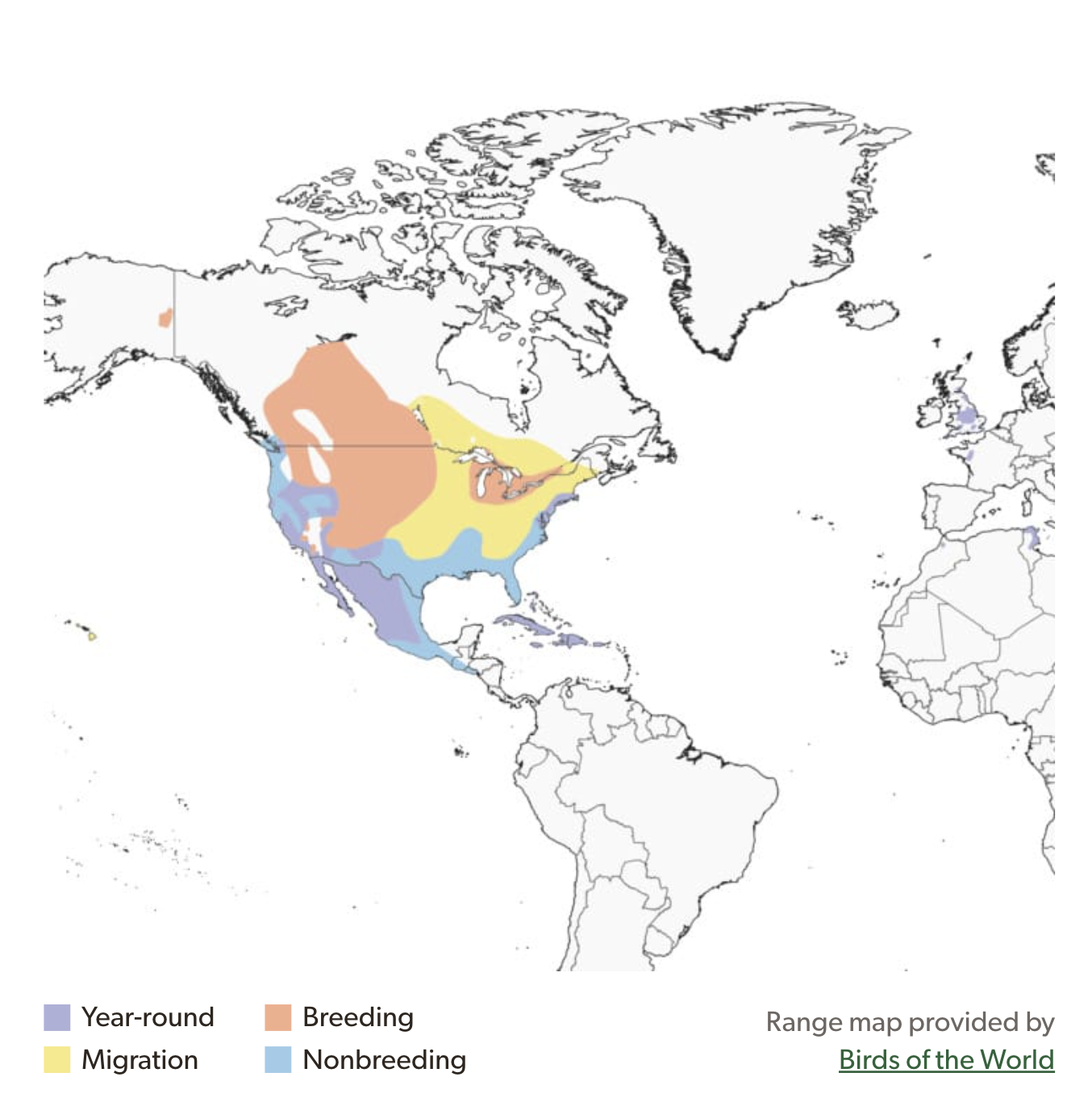

The Ruddy Duck is the most abundant stiff-tailed duck in North America (Johnsgard 2010). In British Columbia, Ruddy Ducks can be found breeding in the interior or wintering along the coast (Johnsgard 2010). Their range includes southern Canada from west to east and almost all of the US and Mexico (All About Birds). The main breeding ground is central North America, with about 86% of the breeding population in the prairie pothole region (All about birds Ruddy Duck). A Ruddy Duck’s preferred breeding location will have marshy areas containing open water (fresh or alkaline) and dense plants upon which they can build their nests (Johnsgard 2010). In the winter they are partial to brackish bays and other coastal areas but still frequent wetlands (All about birds Ruddy Duck).

Breeding and Behaviour

Ruddy ducks are unique among ducks for their breeding behaviour. Despite their innocent appearance, males are known for being aggressive and promiscuous (Brennan et al. 2017). Unlike most other ducks, they only pair up once reaching the breeding grounds and the partnerships are very short (All about birds Ruddy Duck; Brennan et al. 2017). They experience intense sexual competition and many males often battle for the attention of one female (Brennan et al. 2017). The unique mating display of the male ruddy duck is shown in the video below.

Eggs and Nesting

Ruddy Ducks lay the largest eggs (proportional to body size) of all waterfowl (All About Birds Ruddy Duck). They sometimes engage in parasitic egg laying, by laying eggs in the nests of other birds of their own or other species (Audubon). Fortunately for their victims, the young require little care as they are fairly developed at hatch (Audubon).

Part II – Research

Helping Drive the White-headed Duck to Extinction

Photo of a White-Headed Duck by Otgonbayar Tsend https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/94227671

The Ruddy Duck has an unfortunate history in Europe. The species was introduced to the UK in the 1950s and soon established populations in multiple European nations (Robertson et al. 2015). The already endangered White-Headed Duck, a stiff-tailed European relative of the Ruddy Duck, had its population further reduced due to interbreeding between the species (Robertson et al. 2015). A cull began in the 1980s to kill all Ruddy Ducks and Ruddy/White-Headed Duck hybrids in an attempt to rescue the native species (Robertson et al. 2015). By the year 2000, there were approximately 6,000 Ruddy Ducks in the UK (Robertson et al. 2015) but that number was brought down and in 2021, it was reported that there were likely 10-15 Ruddy Ducks remaining in the UK (Brown 2021). White-Headed Duck numbers in Europe increased from just 22 individuals in 1977 to over 2,500 individuals in 2021 (Brown 2021). Things may have settled down in Europe, but there is some concern that Ruddy Ducks might begin a similar takeover in the Caribbean by outcompeting another of their relatives, the masked duck (Goodman et al. 2019).

Blue bills – Colour and Colour Change in Birds

Photo from Ducks Unlimited https://www.ducks.ca/species/ruddy-duck/

As mentioned in the ID section of this blog, the bill of a male ruddy undergoes a colour change from dark brown to pale blue in preparation for breeding. This may have left you curious as to how this happens. In many bird species, ducks included, the males molt and acquire flashier plumage for the breeding season. In male ruddy ducks, this occurs during a prealternate molt in the spring, through which they acquire their distinctive “ruddy” (or rufous) colour (Pyle 2005). Pigment deposition in feathers is controlled, at least in part, by hormones (Pyle 2005). But what if it’s not feathers that are changing colour, and what if the colour doesn’t come from a pigment?

The colour blue, like the sky-blue bill of a male Ruddy Duck in breeding plumage, is typically a structural colour in birds. Structural colours are seen in bare parts of birds (like legs, bills, and the skin around the eye) as well as in plumage. Structural colours are produced when light reflects off microscopic structures in tissues; in bare parts (like the bill) this would likely be collagen fibers (Price-Waldman & Stoddard 2021).

Research on the exact mechanism of bill colouration in Ruddy Ducks was difficult to find, but a paper by Hays and Habermann from 1969 describes the dissection of Ruddy Duck bills. They discovered that there was, indeed, no blue pigment, confirming that the blue colour we see is structural. They found a layer of black, which they determined to be the brown or black pigment, melanin, beneath a thin surface layer (Hays and Habermann 1969). They elucidated that some structural characteristic of the surface layer and/or the melanin beneath it resulted in the blue colouration (Hays and Habermann 1969). But how does the bill change from brown to blue and back again?

Studies have found that bare parts of birds can change colour much quicker than plumage (Iverson & Karubian 2017), which makes sense considering that feathers must be moulted and then replaced to induce a colour change. In fact, the cere (the fleshy upper part of the bill in some species) can change colour within seconds in male Crested Caracaras; but the colour in this case comes from hemoglobin, not a structural colour (Iverson & Karubian 2017).

Lahaye et al. (2014) did an interesting experiment with female budgerigars where they found that structural colour on bare parts (in their case ceres) of the bird could cause relatively quick colour changes in response to testosterone. Exactly how testosterone does this doesn’t seem to be well understood but Lahaye et al. (2014) advised that it may alter the microscopic structures in the skin, or affect the pigments present in the skin, resulting in a colour change (pp. 9). They suggested that “[testosterone] may cause a withdrawal of melanin from the outer tissue layers of the cere, revealing the potential underlying blue structural color” (Lahaye et al. 2014 pp. 9).

In Ruddy Ducks, an influx of testosterone might result in the removal of melanin from the subsurface of the bill, leading to the expression of the blue structural colour. This seems to agree with the results from Hays and Habermann’s dissection of Ruddy Duck bills. There is abundant research on mechanisms of colouration in avian plumage but there seems to be significantly less on the colours of bare parts, specifically on the structural colouration of bare parts. Hopefully there is more to come.

Thank you for taking the time to read my blog.

References

All About Birds. (n.d.) Mallard. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Mallard/

All About Birds. (n.d.) Ruddy Duck. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ruddy_Duck/overview

Audubon. (n.d.) Ruddy Duck. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/ruddy-duck

Brennan P. L. R., Gereg. I., Goodman, M., Feng, D., & Prum, R. O. (2017). Evidence of phenotypic plasticity of penis morphology and delayed reproductive maturation in response to male competition in waterfowl. The Auk, Vol. 134 (4), pp. 882-893. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90014208

Brown, P. (2021, Dec 22). Specieswatch: 10 to 15 ruddy ducks left in UK after Europe-wide cull. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/22/specieswatch-10-to-15-ruddy-ducks-left-in-uk-after-europe-wide-cull#:~:text=Peak%20numbers%2020%20years%20ago,Oxyura%20leucocephala%2C%20of%20southern%20Spain.

Goodman, N. S., Eitniear J. C., & Anderson, J. T. (2019). Time-activity budgets of stiff-tailed ducks in Puerto Rico. Global Ecology and Conservation, 19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00676

Hays, H., & Habermann, H. M. (1969). Note on Bill Color of the Ruddy Duck, Oxyura Jamaicensis Rubida. The Auk, Vol. 86 (4) pp. 765-766. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/auk/vol86/iss4/34

Iverson, E. N. K., & Karubian, J. (2017). The role of bare parts in avian signaling. The Auk, Vol 134 (3) pp. 587-611. https://academic.oup.com/auk/article/134/3/587/5149285

Johnsgard, P. A., “Waterfowl of North America: Stiff-Tailed Ducks, Tribe Oxyurini” (2010). Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010) by Paul A. Johnsgard. 14. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciwaterfowlna/14

Lahaye, S. E., Eens, M., Darras, V. M., & Pinxten, R. (2014). Bare-part color in female budgerigars changes from brown to structural blue following testosterone treatment but is not strongly masculinized. PLoS One. Vol 9 (1) pp. 1-11. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3901734/ .

Price-Waldman, R., & Stoddard M. C. (2021). Avian Coloration Genetics: Recent Advances and Emerging Questions. Journal of Heredity, Vol 112. (5) pp. 395-416. https://academic.oup.com/jhered/article/112/5/395/6272461

Pyle, P. (2005). Molts and Plumages of Ducks (Anatinae). Waterbirds Vol. 28 (2), pp. 208-219. https://doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2005)028[0208:MAPODA]2.0.CO;2

Robertson, P.A., Adriaens, T., Caizergues, A., Cranswick, P. A., Devos, K., Gutiérrez-Expósito, C., Henderson, I., Hughes, B., Mill, A. C., & Smith, G. C. (2015). Towards the European eradication of the North American ruddy duck. Biological Invasions, Vol 17, pp. 9–12. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1007/s10530-014-0704-3

Nice work, Emma! They are very cute little ducks. you mentioned they can occasionally act as brood parasites; do they have any detriment to host young? for example if they are well developed at hatch, do they attempt to kill other hatchlings, or do they just go off on their own immediately?

Thanks

Marcel

Thanks Marcel! I didn’t encounter any suggestion that the parasitic nestlings have a direct negative impact on the other hatchlings. Ruddy ducks are very well developed at hatch, they require little parental care and leave the nest in a day or so. But I imagine that they do steal some resources from the other nestlings; for example the parents might not be able to incubate all the eggs. Thanks for commenting!

Nice blog! I’ve never thought about how bare parts change on a duck before; it’s interesting that the Ruddy’s colour comes from a structural mechanism. I think the Ruddy is more handsome then the White-Headed Duck, so it makes sense that they out competed them in Europe. I’m glad that the native White-Headed’s population was able to bounce back.

Thank you! I found the colour changing mechanisms really interesting. Yes, Ruddy ducks are handsome little guys and very competitive breeders. Thank you for commenting!

Wow, this is really amazing!! It’s interesting how they migrate more inland for breeding then come back out to the coast for the rest of the year. I’m wondering, do they not care for their young at all? Even after they hatch? Also when do they engage in parasitic laying? Is it anytime the opportunity presents itself and to any other bird species also breeding near by or is there some sort of preference?

After reading your blog, I really want to learn more 🙂 great job!

Thanks for commenting Zena! They don’t care for their young very much as they are really well-developed when they hatch and only stay in the nest for a day or so. After that, the mom will watch after them a bit but I believe they feed themselves for the most part. The dads are not involved at all… I’m not too sure when they would choose to engage in parasitic egg-laying but I imagine it’s fairly opportunistic.

Thanks!

Emma

What a cute duck!!! I love the Ruddys now more than ever 🙂 Thanks for the awesome post.

I’m curious about the decline in the White-Headed Duck population in the Carribean. How is it exactly that they are being outcompeted? Is it that the Ruddys are better at exploiting a certain resource? Or is it a particularly sensitive species that is being disrupted by this brutish introduced duck?? Lol!

Thanks again 🙂

Thank you!

They are worried about the Masked Duck population in the Caribbean because they’ve noticed that Ruddy Ducks are expanding their range in that area. In Europe, interbreeding was a major factor in outcompeting White-Headed Ducks (they are very sexually competitive and were able to reduce the population of ‘pure’ White-Headed Ducks) and I believe they are worried about something similar happening to the Masked Ducks. However, I didn’t read anything that said that explicitly.

Thanks for your question 🙂

Emma

Great post, Emma!

Thank you for introducing me to their nickname “Butterball”, how cute. I didn’t know that they were most active at night and now my goal is to see a little sleepy Butterball during the day. Where would I find them? Do they sleep floating on the water or can I find them curled up on the shore at the edge of the wetland?

Wow, what a wild history of their population in Europe- is there any more recent research on whether the number of native White-Headed Duck remain or did the Ruddy duck population bounce back since they seem to be such great competitors? Or maybe the odds of them bouncing back with only 10-15 individuals left would be too low? I wonder how many individuals it took to take over in the first place. I don’t enjoy the idea of killing Ruddy Ducks, but they are probably staying on top of that now compared to when they were first introduced.

I was wondering how they get such bright blue bills during breeding and the research you found is super interesting!

Thank you for such an insightful read, you did a great job describing this species!!

Thank you!

That is one of my goals as well! From what I understand they will sleep on the water, often in groups, and they might hide in the reeds. They generally avoid being on land because they are not very good at walking… and they will dive to avoid predators.

They plan to have Ruddy Ducks functionally extinct in Europe by 2025 and from what I’ve seen, they are on track. Yeah, it was not my favourite topic to research.. poor little butterballs…

Thanks for reading!

Emma

Thanks for your reply, Emma. It makes sense that they would just snooze on the water, along with the reassurance of safety in groups and amongst the reeds. It’s good to hear that they seem to be on track with the extinction in Europe. It is an unfortunate fate for the butterballs, but every duck has its place!

Great post Emma! Ruddy ducks are so cool, I had no idea they were aggressive they look so cute. So cool that birds can change there own colour faster then their feather I would have never thought of that!

Thanks for reading!

Yes, they are very cute and very aggressive. Bird colouration is a fascinating topic and there is a lot of cool research out there. Evolution has resulted in some pretty amazing things.

Awsome blog, good job!

This class opened my eyes to all the ducks in BC but the blue bill on the ruddy duck definitaly caught my attention! I was sure it was due to a pigement and reading that it is actually a color change due to structural changes was very cool.

I also did not know there was such thing as a duck that is more active at night, I wonder why they evolved this adaptation?

Thanks for reading!

I’m not sure why they are more active at night. They are small ducks so maybe its a way to avoid predators and have less competition during feeding? But I’m not sure.

Thanks,

Emma