OVERVIEW

Taxonomy

- Class – Aves (like all birds)

- Order – Podicipediformes (meaning “rear foot” in Latin, their legs are closer to the back than the front to help with diving and swimming… not so great for walking)

- Family – Podicipedidae

- Genus – Aechmophorus (meaning “spear-bearing” in Greek, for their stabby bill)

- Species – occidentalis (Western)

Identification

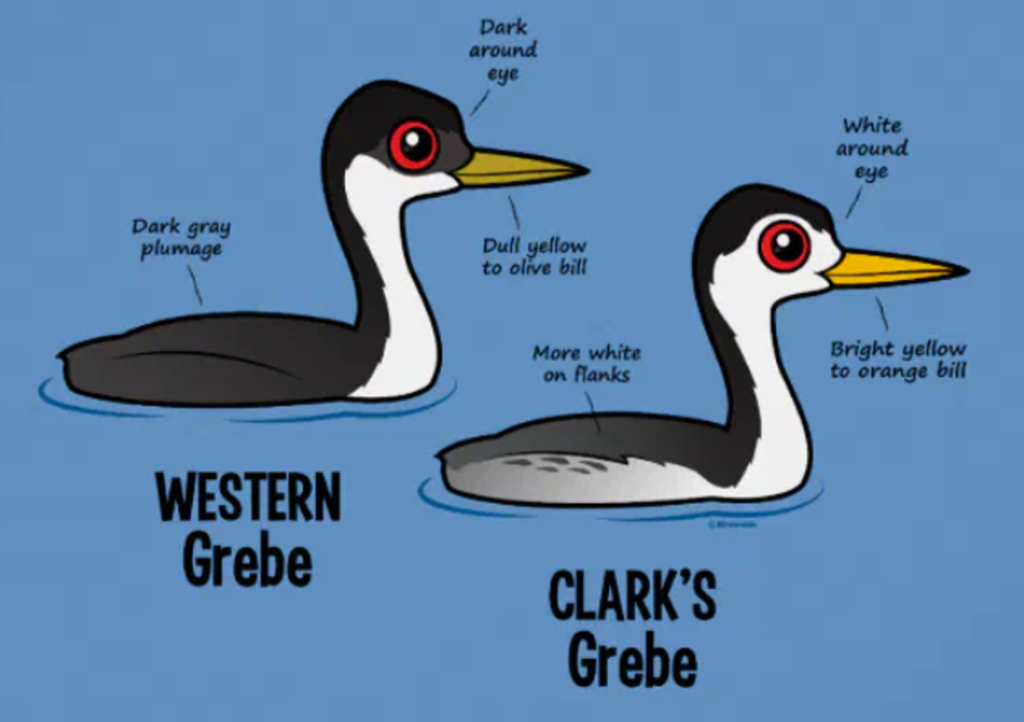

Usually found sporting an elegant black and white tuxedo on its swan-like neck, a dark cap that extends below fiery red eyes and meets a bill of dull olive-yellow.

Not to be confused with similar-looking species: Clark’s Grebe (black cap does not extend below the eye) or non-breeding Red-necked Grebe (eyes are black, neck is gray-washed, and flanks have more white feathers). Hybrids of Western and Clark’s Grebes also occur on occasion, making them VERY close relatives. (CLO, 2020)

Males and females look practically the same, although females tend to have a slightly smaller bill. Western Grebes live up to 8 -11 years, are roughly crow-sized (2-ft long by 2-ft wide wingspan), and weigh approximately 1 to 1.8 kg (BirdLife, 2019 & CLO, 2020).

Not so fun fact: Their dense and waterproof plumage was so coveted in the nineteenth century, that grebes were hunted to endangerment in the name of fashion. (CLO, 2020)

HABITAT DISTRIBUTION

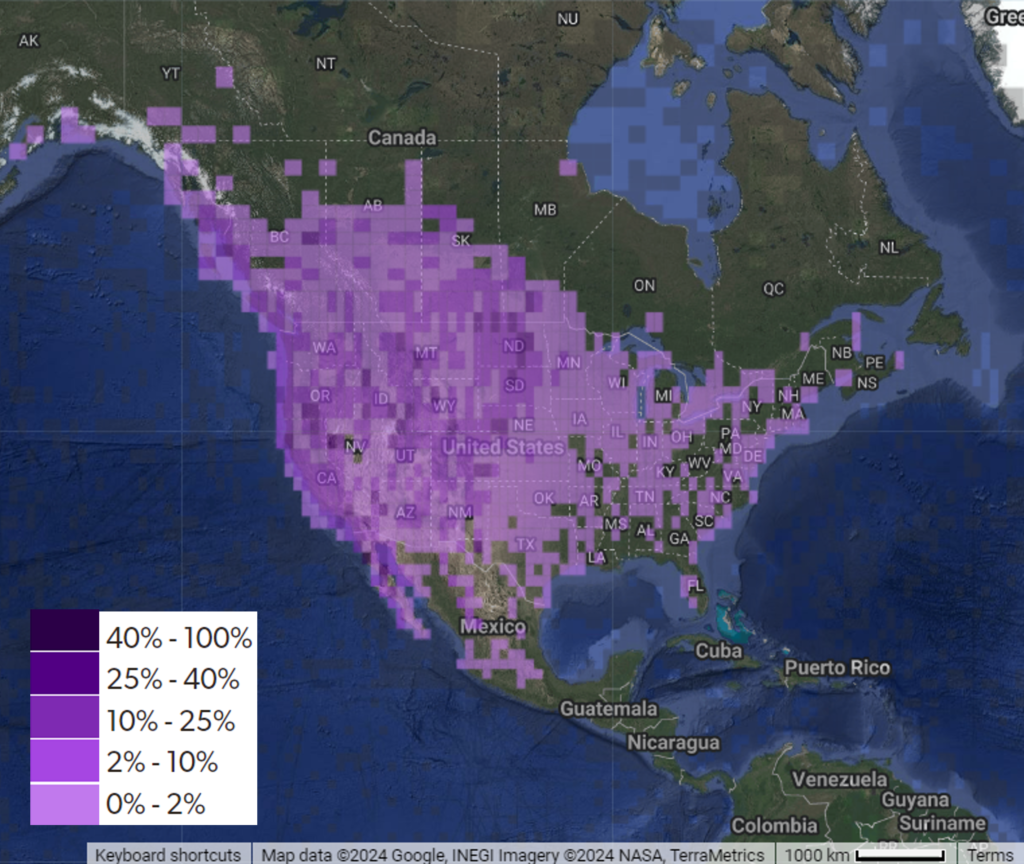

Endemic to western North America, the range of Western Grebes extends as far east as Manitoba. Of the Canadian population, less than 2% reside in BC, 60% live in Alberta, 10% in Saskatchewan, and 30% in Manitoba (ECCC, 2022). In the spring and summer, they breed in inland lakes and wetlands, then migrate back in the fall to warmer coastal areas (left image below). A single large lake may contain a colony of hundreds of mating pairs (CLO, 2020). The image on the right shows the frequency of sightings for a set of 700,000 recorded observations on eBird (2024).

BEHAVIOUR

As excellent swimmers with lobbed toes, they spend most of their time in the water, where they dive for prey, eat, rest, and nest, not necessarily in that order (CLO, 2020). And graceful as they may seem, they can be slightly awkward outside of their natural watery element:

Reproduction

Ever sticklers for romance, Western Grebe mates employ two sequential courtship displays referred to as “ceremonies” (CLO, 2020). But first, sit back and enjoy the relaxing sound of gears grinding, err, courtship: (Audubon)

1) Rushing ceremony – it begins with a shrill “kreet-kreet”, followed by bill dips, head shaking, dancing, and finishing off with a sudden dive. The “Rush” is performed by either mating pairs or males trying to show off, as seen in BBC Life: The Grebes (narrated by the one and only, David Attenborough):

Truly majestic.

Don’t quote me on this, but I’m pretty sure J.T. got inspiration for his dance moves by Western Grebes’ rushing ceremony. (YouTube)

2) Weed ceremony – you read that right, part 2 of the mating ritual involves “weed dancing”. After warming up with some neck stretches, the mating pair dives down into the watery depths, then comes up to the surface with a bill-full of weeds to twirl and spiral around one another in synchrony (CLO, 2020)… if that’s not romance then I don’t know what is.

Nesting & Brooding

After their impressive ritual, the mating pair build (or steal) floating nests on emergent vegetation such as rushes and reeds, typically in waters that are less than one metre deep. (Audubon, 2024). They are quick to exploit recently abandoned empty nests within a colony, to avoid the heavy cost of building a new one (Hayes & Turner, 2017).

Eggs are pale bluish-white to brown, and get incubated for about one month (CLO, 2020). A clutch may contain anywhere from 2 to 6 eggs (Audubon, 2024).

Hatchlings are carried on their parents’ back, and fed a diet of insect larvae and small fish (CLO, 2020). A few weeks after hatching (and after some futile begging) these fast-growers are free to dive and feed on their own, having grown their formative plumage (CLO, 2020). At the ripe age of ten weeks-old, they may spread their wings and take their first flight (Audubon, 2024). As adults, their diet transitions into crustaceans, aquatic worms, insects, and larger fish (CLO, 2020).

Fun fact about preening: They sometimes swallow their own feathers, but not to worry, they are believed to protect the stomach lining from possible fish-bone punctures, and help to regurgitate undigested food pellets with elegance and grace (CLO, 2020).

CONSERVATION STATUS

| Jurisdiction | Status | Agency (Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Provincial (BC) | Red List (At Risk), S1S2 – critically imperiled to imperiled | NatureServe (2023) |

| Federal (Canada) | SC – Special Concern | COSEWIC (2014) & SARA (2017) |

| Global | Least Concern (LC) | IUCN (2019) |

Western Grebes are federally protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1994, and under the United States Migratory Bird Treaty Act, since the majority of the population winters in warmer U.S. regions (ECCC, 2022).

Global population is estimated at 100,000 individuals, with 30% residing in Canada (ECCC, 2022). Within their colonies, population density is roughly 70 individuals per square-kilometre (COSEWIC, 2014).

One of the main conservation challenges includes habitat loss of nesting grounds due to more frequent wildfires and human disturbance (Audubon, 2024). Grebes are also susceptible to water level fluctuations, chemicals in their environment (mainly pesticides and oil), marine vessel disturbances, gill nets, and collisions with energy infrastructure such as powerlines and wind turbines (ECCC, 2022, Fox et. al, 2016, & CLO, 2020).

IN CULTURE

In Ojibwe oral tradition, Grebe is given the name of “Hell-Diver” for their ability to withstand harsh conditions set by the Spirit of Winter through resourceful diving for food. Hell-Diver’s care for other waterfowl friends, Mallard and Crane, feeds the fire that eventually brings the onset of spring (Milwaukee Public Museum, 2022).

LATEST RESEARCH

Drone Surveys Aid Habitat Conservation

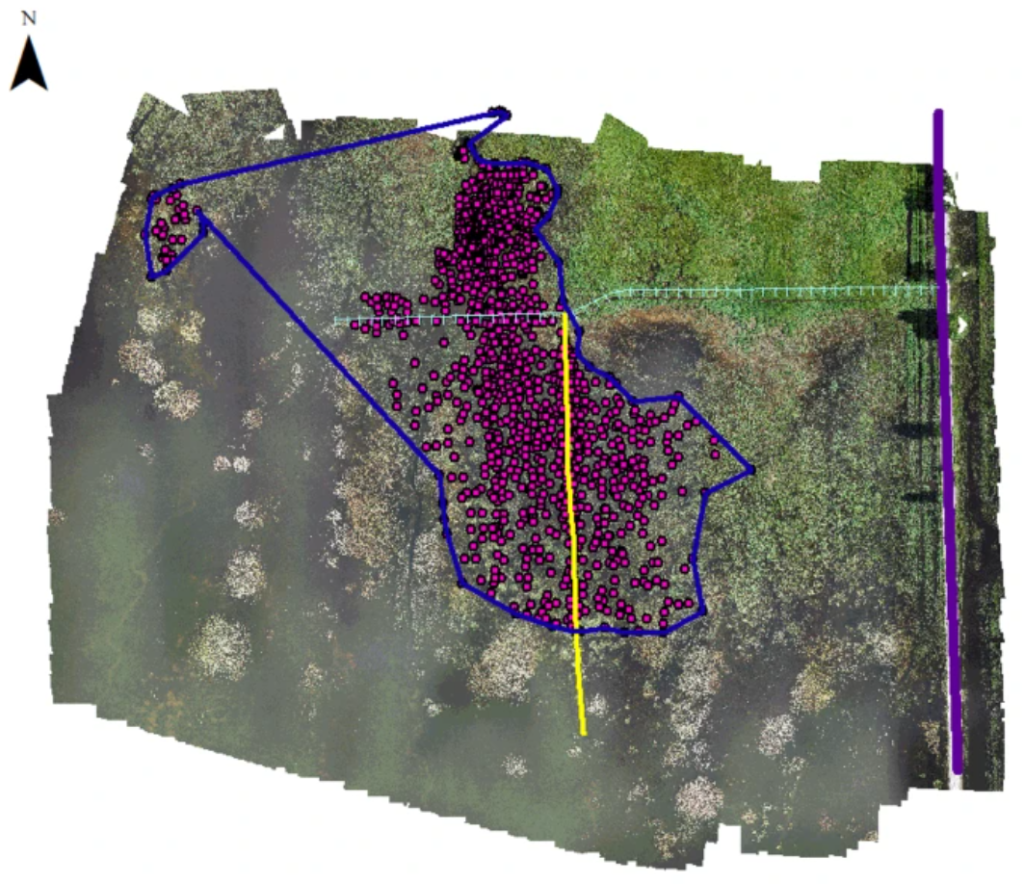

Drone surveys have been shown to help with investigations of nest surveys in inland aquatic habitats. In a study by McKellar (2022), high-resolution imagery illustrated aerial coverage of rooted aquatic vegetation in wetlands. As predicted, decreasing size of open-water areas correlated with more crowded nesting sites in the centre (pink dots on the left image below), and increased competition for sites that were far away enough from shore to avoid predation.

The results provided an insight into the advantages or disadvantages of grebes aggregating into bigger colonies. Drone surveys can also be used in conjunction with ground-based surveys, which obtain fitness measurements based on the survival rate of eggs and juveniles. This remote monitoring application has the potential to identify rapidly-changing habitats at target areas, on a more frequent basis, to facilitate real-time implementation of conservation measures (McKellar, 2022).

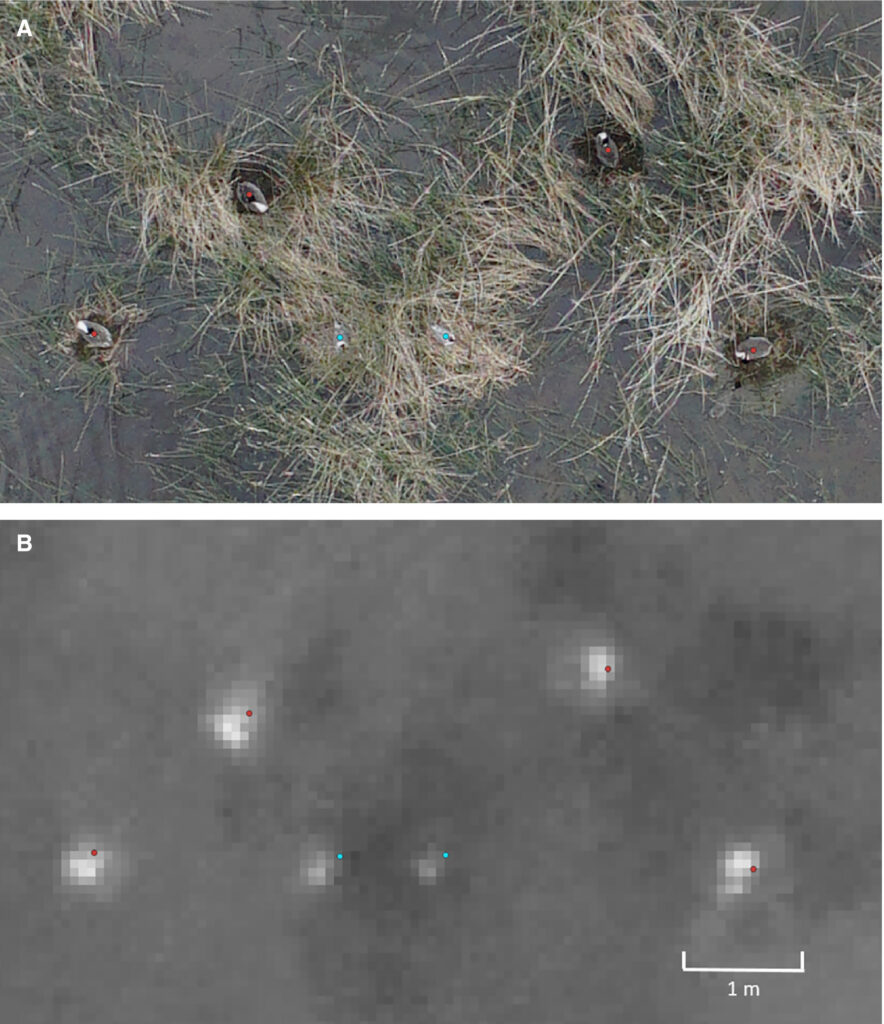

In wetland areas that are both limited by ground access, and visually cryptic from an aerial perspective, drones with dual visible-thermal cameras managed to accurately identify nest sites with eggs based on their heat signatures, with results that were within 5% of a ground-based survey that was conducted in synchronicity (McKellar et. al, 2021- images above on the right).

Another study that used drone surveys demonstrated that nesting Western Grebes prefer intermediate water depths in any given body of water, within a range of 40-80 cm (Lachman et. al, 2022). The researchers make a point that drone surveys should be specific to fit the requirements of each specific site and species. These are feasible due to the lower cost and ease of deployment of drones, increasing image resolution and storage capabilities, and lower invasiveness by avoiding interactions with resident waterfowl.

Thank you for reading!

If you made it this far, please leave a comment below and subscribe…

REFERENCES

BirdLife International (BirdLife) (2019). Western Grebe: Aechmophorus occidentalis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved September 2024, from https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22696631A139355294.en.

British Columbia Conservation Data Centre (BC CDC) (2024). BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Ministry of Environment. Retrieved September 2024, from https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/

Cornell Lab of Ornithology (CLO) (2020). Western Grebe. All About Birds. Retrieved September 2024, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Western_Grebe/

COSEWIC (2014). COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Western Grebe, Aechmophorus occidentalis, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Retrieved September 2024, from https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/466562/publication.html

eBird (2020). Western Grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved September 2024, from https://ebird.org/species/wesgre

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) (2022). Management Plan for the Western Grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series. Retrieved September 2024, from https://wildlife-species.az.ec.gc.ca/species-risk-registry/virtual_sara/files//plans/mp_western_grebe_e_final.pdf

Fox, C. H., O’Hara, P. D., Bertazzon, S., Morgan, K., Underwood, F. E., & Paquet, P. C. (2016). A preliminary spatial assessment of risk: Marine birds and chronic oil pollution on canada’s pacific coast. Science of the Total Environment, 573, 799-809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.145

Hayes, F. E., & Turner, D. G. (2017). Copulation Behavior in Western Grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis) and Clark’s Grebe (Aechmophorus clarkii). Waterbirds (De Leon Springs, Fla.), 40(2), 168-172. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.040.0209

Howie, R. (2015). Western Grebe. In P.J.A. Davidson, R.J. Cannings, A.R. Couturier, D. Lepage, and C.M. Di Corrado (Eds.), The Atlas of the Breeding Birds of British Columbia, 2008–2012. Bird Studies Canada. Retrieved September 2024, from http://www.birdatlas.bc.ca/accounts/speciesaccount.jsp?sp=WEGR&lang=en

Lachman, D. A., Conway, C. J., Vierling, K. T., Matthews, T., & Mack, D. E. (2022). Drones and bathymetry show the importance of optimal water depth for nest placement within breeding colonies of western and Clark’s Grebes. Wetlands (Wilmington, N.C.), 42(8), 110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-022-01602-1

Lachman, D., Conway, C., Vierling, K., & Matthews, T. (2020). Drones provide a better method to find nests and estimate nest survival for colonial waterbirds: A demonstration with western grebes. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 28(5), 837-845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-020-09743-y

McKellar, A. E. (2022). Patterns of inter- and intraspecific nest dispersion in colonies of gulls and grebes based on drone imagery. Journal of Field Ornithology, 93(2), 4. https://doi.org/10.5751/JFO-00099-930204

McKellar, A. E., Shephard, N. G., Chabot, D., Horning, N., & Mulero‐Pazmany, M. (2021). Dual visible‐thermal camera approach facilitates drone surveys of colonial marshbirds. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, 7(2), 214-226. https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.183

Milwaukee Public Museum (2022). Ojibwe Oral Tradition. Retrieved September 2024, from https://www.mpm.edu/content/wirp/ICW-141

National Audubon Society (Audubon) (2024). Western Grebe. Retrieved September 2024, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/western-grebe

Sibley, D. A. (2016). The Sibley field guide to birds of western North America. (2nd ed.). Alfred A. Knopf.

What a fascinating post! I had no idea Western Grebes had such elaborate courtship displays, those “weed-dancing” ceremonies are surprisingly elegant! The information on their nesting and brooding habits, especially their tendency to use abandoned nests, was also really interesting and showed how efficient they are.

It’s also great to see that drone technology is now helping researchers monitor Western Grebe habitats with minimal disturbance! Do you think advancements in drone technology will continue to play an even bigger role in future conservation strategies for other waterfowl species? Or have drones mostly reached their potential in what they can contribute?

Thank you for a terrific read!

Thanks for your comment Emily! I suspect that as technology continues to advance, aerial drones will gain features that makes them even more user-friendly and inconspicuous, which would allow us to get closer to these nests and gather images/ video without having to trek through the bush as much 🙂 Image resolution might have reached its limit though, from a practical standpoint.

Great post Isabel!

I had no idea that Grebe feathers were used for fashion, and it’s so unfortunate that they didn’t get a chance to make that big of a comeback since they are still provincially red-listed! And how sad but predictable is it to see human disturbances as the main driver… Hopefully an increase in the drone monitoring you mentioned will help better understand their breeding habitats and what the next steps for conservation may be so that they have sufficient nesting grounds! I’ve had drones fly over me and can hear the swarming sound overhead. Do you think it disturbs the Grebes at all, maybe thinking it’s a potential threat, or is the resolution so great that they can stay far enough away that won’t hear it?

I love the video of the Grebe walking on the beach. That’s pretty much what I look like when I try to walk around while wearing high heels. Actually, the Grebe is much more elegant than me…

Grebes eating their feathers is such a cool fun fact and scientists have been unsure of the exact evolutionary reason for this behaviour for over 500 years! The paper I read is called Feather-Eating in Grebes: a 500-Year Conundrum by Joseph R. Jehl Junior. The main supported hypothesis appears to be that the feathers aid in digestion, trapping the food for a longer period of time so that chemical digestion can do its thing. The points you mentioned about protecting the stomach lining and expelling hard-to-digest materials are also discussed and have not been proved wrong, I believe that they are all somewhat linked without just one single driving factor to their evolution. Super cool!

Thank you for the great read!