Brandt’s Cormorant (Phalacrocorax penicillatus) is a beautiful and courageous marine fishing bird. They are the largest cormorant on the west coast of North America, weighing up to 2.7 kg and having a wingspan of just over a meter (All About Birds). They have wide webbed feet to help propel them underwater, along with a long beak with a slight downward hook at the end. In non-breeding plumage, adults are black over their whole body, and juveniles are brown with a yellow-brown (“buffy”) throat. Adults in breeding plumage, however, have a little extra colour. They keep a large portion of their black feathers, but their eyes and throat pouch become a vibrant blue, and thin whisker-like feathers protrude backwards from their head to their shoulders (All About Birds).

Brandt’s Cormorants are exclusive residents of the west coast of North America, from Alaska to Mexico (Audubon, 2024). Their unwavering dedication to the sea means they are rarely spotted inland, and they seldom venture more than 16 kilometres from the shore until it’s time to migrate (All About Birds). Their love for the ocean has honed their fishing skills, making them elegant divers capable of plunging 100 meters in search of delectable fish and squid, which they chase with their powerful webbed feet and crush with their strong beak (U.S. National Park Services, 2021; All About Birds).

When compared to other seabirds, Brandt’s Cormorants are able to breed quite early in their life (as young as two years old). This allows them to delay reproduction in unfavourable years until the conditions are just right (Boekelheide & Ainley, 1989). When it’s time to nest, male cormorants embark on a charming courtship ritual. They scout a perfect, sloped spot on the windward side of an island or offshore cliff in the California Current and gather nesting materials like grass, sticks, and algae, often before their mate even arrives (All About Birds). To win a female over, the male cormorant performs a captivating display, inflating his stunning blue throat pouch and pumping his head up and down while fluttering his wings. Once he catches her eye, they engage in a bill-clasping dance, swaying side to side.

Female Brandt’s Cormorants will typically lay a clutch of between three to six eggs, and the male will help her care for the eggs and, when they hatch, the chicks (U.S. National Park Services, 2021; Audubon, 2024). The parents take turns feeding, brooding, and shading their chicks, all the while building the nest around their young together (U.S. National Park Services, 2021; All About Birds). Once the chicks grow up and leave their nesting site, the parents may decide to return to the same nest every year and continue to build it up (Audubon, 2024).

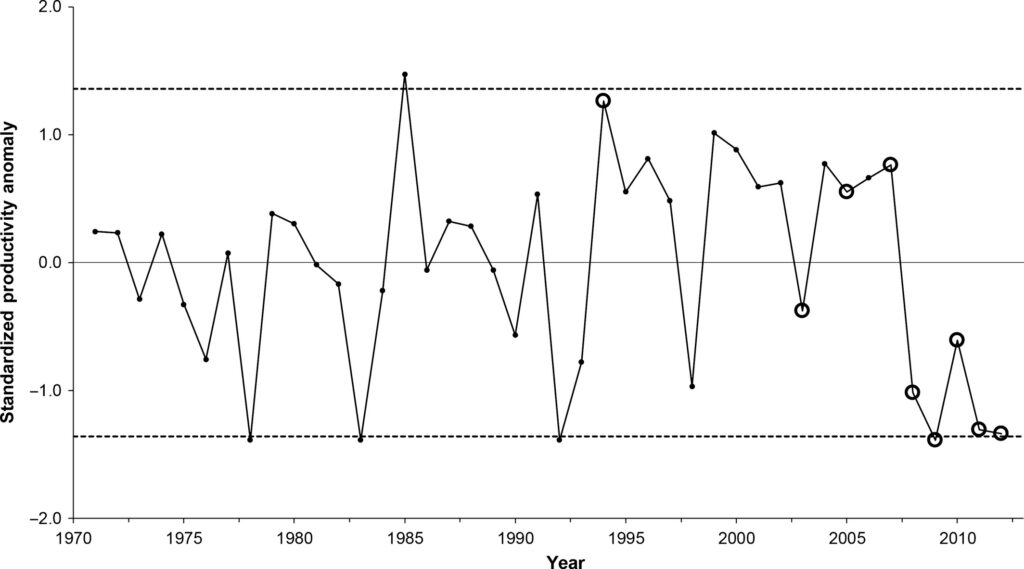

Although the IUCN Red List labels Brandt’s Cormorants as “low concern,” the global population is currently in decline, with the loss of about 50,000 individuals recorded from 2002 to 2017 (Zehel 2024; All About Birds). Additionally, local populations are subject to fluctuations, as seen in a study published in 2016 that showcased the extreme changes in productivity in Brandt’s Cormorants (Elliot et al., 2016; Audubon, 2024).

Brandt’s Cormorants are especially susceptible to anthropogenic interference like most vulnerable species. They are susceptible to oil spills, pesticides, and chemical pollution, and are usually more affected by oil than other marine birds because of buildup on the coastline, where they forage for nesting material (All About Birds; U.S. National Park Services, 2021). Another significant threat to these Brandt’s Cormorants is human disturbance: boating, fishing, diving, fireworks and research visitations can all cause cormorants to leave their nests for some time or, in some severe cases, permanently (All About Birds; U.S. National Park Services, 2021; Zehel, 2024). Deserting their nests leaves their eggs vulnerable to predators like gulls, who will not hesitate to eat anything left out for them (All About Birds; U.S. National Park Services, 2021).

As mentioned above, human disturbance is a major cause of the decline of Brandt’s Cormorants. Whether the acts are direct (i.e. shooting) or indirect (i.e. recreational activities), there has been a significant adverse effect recorded on Brandt’s Cormorants and hundreds of other species around the globe (All About Birds, Bateman et al., 2023; U.S. National Park Services, 2021). In recent years, human activity surrounding coastal regions has increased, leading to interactions both in the ocean and on the coastline, especially at their scenic breeding grounds. Seabirds are the most jeopardized birds, having over 25% of their species under a “threatened status” (Buxton et al., 2017).

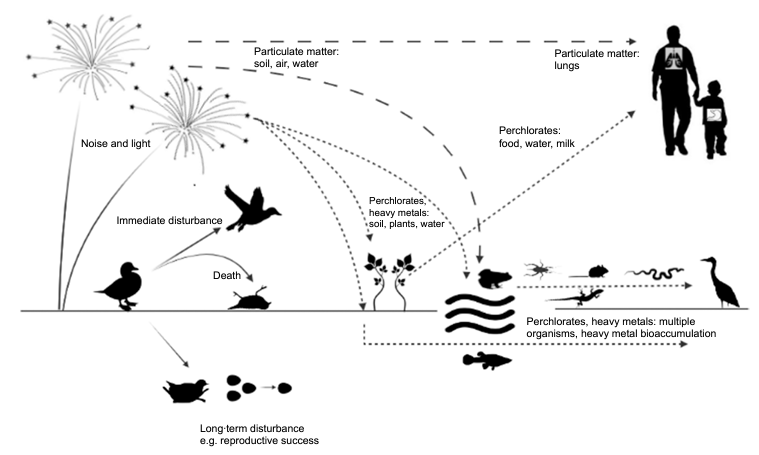

The negative effect of human noise pollution on wildlife has long been a considered problem since at least the 1960s (Engel et al., 2024). Fireworks, for instance, are often entirely overlooked by the public when it comes to their effect on wildlife. This can be a shock, especially when considering how domesticated animals react, with 74.4% of companion animals in New Zealand having a phobia of fireworks. These fears aren’t always harmless either, with reports of these animals frantically running and injuring themselves. If often enough, some of these animals can even develop a fear of nightfall, which could typically indicate a fireworks display (Bateman et al., 2023). Now imagine the effects of fireworks on wildlife outside of the regular hustle and bustle of human society. Brandt’s Cormorants are among the many species affected by these displays and may even be affected more than other bird species. It has been observed that birds that nest in colonies in the open have a more intense reaction than birds in covered forests, as they feel more exposed to the event (Bateman et al., 2023). In fact, LeValley observed that fireworks in California caused the decline of colonizing Brandt’s Cormorants (Bateman et al., 2023).

Efforts are being made to help minimize the effects of human disturbance on seabird colonies like Brandt’s Cormorants: building barriers around nesting sites, setting “setback distances,” and even creating blinds are all efforts to reduce the human-bird interaction (Buxton et al., 2017). With the rapid development off the coast of California and increasing tourism, anthropogenic effects on the California Current System (where Brandt’s Cormorants and hundreds of other species nest) are growing, and extra conservation efforts will be needed to protect and keep Brandt’s Cormorants in their natural ecosystems (Buxton et al., 2017).

References

Audubon. (2024, September 5). Brandt’s Cormorant. Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/brandts-cormorant

Bateman, P. W., Gilson, L. N., & Bradshaw, P. (2023). Not just a flash in the pan: short and long term impacts of fireworks on the environment. Pacific Conservation Biology, 29(5), 396–401. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC22040

Boekelheide, R. J., & Ainley, D. G. (1989). Age, Resource Availability, and Breeding Effort in Brandt’s Cormorant. The Auk, 106(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/106.3.389

Buxton, R., Galvan, R., McKenna, M., White, C., & Seher, V. (2017). Visitor noise at a nesting colony alters the behavior of a coastal seabird. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 570, 233–246. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12073

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Brandt’s cormorant life history, all about birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Brandts_Cormorant/lifehistory

Elliott, M. L., Schmidt, A. E., Acosta, S., Bradley, R., Warzybok, P., Sakuma, K. M., Field, J. C., & Jahncke, J. (2016). Brandt’s cormorant diet (1994–2012) indicates the importance of fall ocean conditions for northern anchovy in central <scp>C</scp> alifornia. Fisheries Oceanography, 25(5), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/fog.12169

Engel, M. S., Young, R. J., Davies, W. J., Waddington, D., & Wood, M. D. (2024). A Systematic Review of Anthropogenic Noise Impact on Avian Species. Current Pollution Reports, 10(4), 684–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40726-024-00329-3

U.S. Department of the Interior. (2021, May 21). Brandt’s cormorant (U.S. National Park Service). National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/brandt-s-cormorant.htm

Zehel, L. (2024, July 4). Species spotlight: Brandt’s Cormorant. Defend Them All Foundation. https://www.defendthemall.org/blog/2024/7/3/species-spotlight-brandts-cormorant

What an informative blog! I loved learning about the cormorants! Such interesting birds!

Really interesting to read, Alex. I had no idea that fireworks had such a big impact on seabirds and their nesting habitats. I wonder if there is any issue with the smoke and debris as well as the noise.

The amount of disruption this species is vulnerable to is concerning. Based on the current estimates of Brandt’s cormorant populations and your own research, do you think the IUCN should re-assess the “Least Concern” listing to something more severe?