A Journalistic Recollection of One Migration and Breeding Season of the Townsend’s Warbler

Adult Townsend’s Warbler. Photographer: Corey Hayes May 24, 2015 Banff, AB. https://www.flickr.com/photos/corey-hayes/18948114528/

Townsend’s Warbler

Setophaga townsendi

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Parulidae

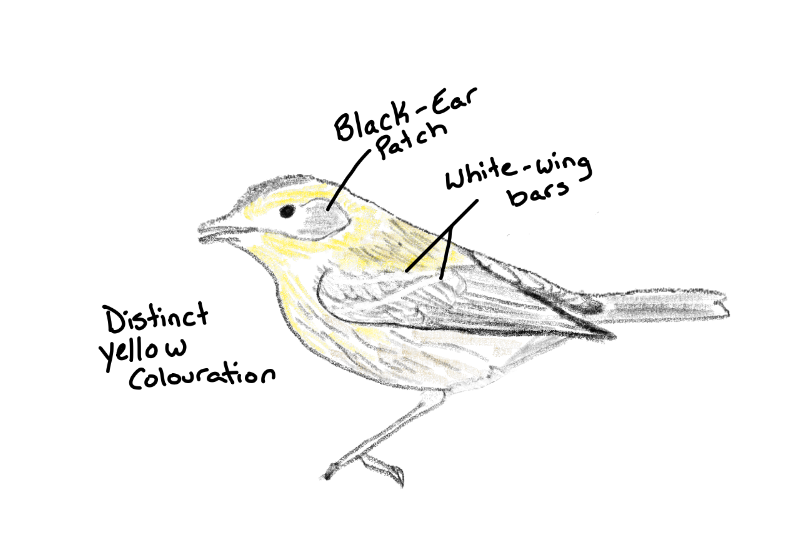

I have fond memories of the first time I heard the distinct call of the Townsend warbler. It was after a grueling 15-day expedition deep within the Canadian wilderness. There I was in the cold, damp old-growth coniferous forest of the Pacific Northwest, about to give up and call it quits on our expedition when suddenly I heard the ethereal song buzzing from the treetops. One individual flew down to eye level, as I instinctively grabbed my journal and jotted a quick sketch of the mysterious handsome bird along with any other details so that the fleeting moment wouldn’t leave my mind.

It would be another few months before I found out the identity of my new friend, the Townsend’s warbler.

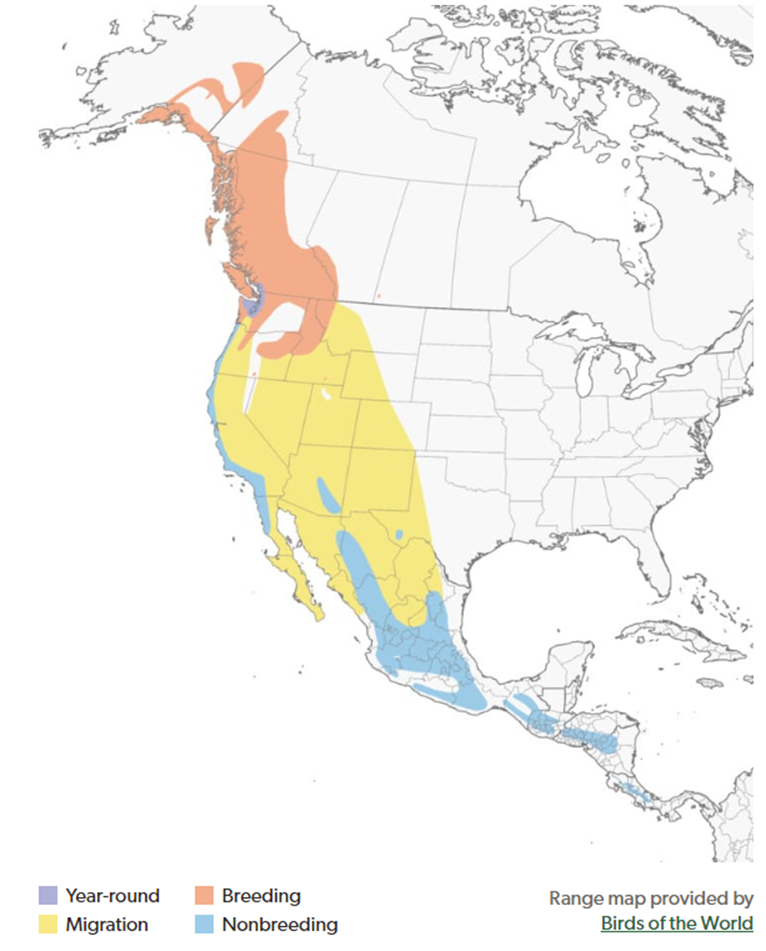

Several years later I would follow the Townsend’s warblers through their entire migration route beginning in South America in March and ending in their breeding ground along the West Coast of Canada and into the southern boarder of Alaska. It is important to note that there are two distinct groups of Townsend’s warbler based on their overwintering location. The group we chose to follow on this expedition overwinter in the South in Mexico or Central America. And the other group of Townsend’s warblers who overwinter in Oregon and Washington state before migrating back up to Alaska (Morrison, 1983).

The following is a first hand account of my travels alongside the Townsend’s warblers.

April 2

We have been following the Townsend’s warblers along their migration route starting at their over wintering grounds down in Mexico for about a month now. Today we have reached Oregon state, and the weather is holding up. Over the last several days I have noticed a peculiar pattern to the songs the Townsend’s warblers are singing. They seem to be singing two very distinct separate songs as they pass through.

Upon further discussion with colleagues, we have decided to separate these songs into two categories, Type 1 and Type 2 (Janes, 2017). After several days of observation, it is important to note that only the males appear to be singing as there are currently no females present. The females are clearly lagging their male counterparts along the migration route by a few days (Pearson & Rowher, 1998).

April 9

I have done some further reading on the usage of the Type 1 and 2 songs during migration. It appears that this behaviour has been observed in other warbler species like Black-throated green warblers who were observed using Type 2 songs during longer distance migrations and switching to the Type 1 song as they approached their breeding grounds (Morse, 1991)

Range map of the Townsend’s Warblers. All About Birds. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Ithaca, NY. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Townsends_Warbler/overview

April 15

Today marks our third day in Washington state. The Townsend’s warblers have been observed interacting with a similar looking species, Hermit warbler. Several of my colleagues have pointed out a few individuals who appear to be a hybrid of the two species. Logically, one could surmise that two closely related wood warblers be able to successfully breed, and therefore it is less surprising to hear, that is exactly what is happening between Townsend’s and Hermit warblers.

One dear friend who has been watching the interactions between the two species mentioned to me that over the years they have noticed how the Hermit warblers have begun to be replaced by the more aggressive Townsend’s warblers (Krosby and Rohwer, 2010). Other eyewitness accounts have noticed more and more hybridized individuals popping up year after year. This suggests that perhaps a subset of male Townsend’s warbler is indeed overwintering in the more Northern States and perhaps they begin breeding with Hermit warblers early to improve their individual fitness.

April 20

The flock of Townsend’s warblers had graced us with their presence. We arrived in the temperate rainforest along the coast of Vancouver Island yesterday. I watched in awed silence, as they danced among the treetops like tiny Christmas ornaments. The warblers preferentially chose the coastal Douglas fir bio geoclimatic zone around Nanaimo, BC. It was hard to believe these tiny colourful warblers had travelled here from their overwintering home in Mexico all the way to the rugged west coast of Canada, and yet here they were, playful as ever, flitting from treetop to treetop. Of course, many of the warblers will choose to stay and breed here among the large Douglas fir trees, but many will continue along their route to find suitable breeding habitat. Today, they were busying themselves foraging on the newly emerged caterpillars, ants, bees, moths, weevils, and stinkbugs located within the thick craggy bark of the Douglas firs (All about birds n.d.).

May 3

The female Townsend’s have been in a flurry today. Rapidly collecting bits of conifer needles, spider webs, twigs, lichen and plant fibers to construct her nest, with no help from her breeding partner (all about birds, n.d.). She will carefully select the tree where she will build the nest. Generally, a very large spruce or fir tree will be the ideal tree, as these trees are relatively common in old growth forests such as those along the west coast of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. The average nesting height is approximately 35 feet above the ground (all about birds, n.d). I suspect this height is chosen to alleviate some of the pressures from ground predators such as cats.

May 8

The female Townsend’s warblers have begun laying their eggs. I have been fortunate enough to be able to peer into a few nests after the female finishes laying and flies off to feed. The eggs are small, no more then 2cm in length (all about birds, n.d.). They are white in colour with brown speckling almost as though they’ve been freckled by the sun. We will continue to monitor the active nests of the warblers and count the number of eggs each female lays.

Townsend’s warblers eggs sitting in a nest. Photographer: Linda Freshwaters Arndt. June 15, 2009. https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-yellow-warbler-nest-with-four-eggs-28101637.html

May 15

It appears the average number of eggs per nest for the Townsend’s warblers is between 3 and 7 (all about birds, n.d.). The more experienced crew members tell me that we should expect to see the first nestlings begin hatching in about 11 to 14 days from now (all about birds, n.d.). Until then there is nothing left to do but continue watching the behaviour of the adult warblers during the day.

June 1

Exciting times are upon us! The eggs have begun hatching! Both parent Townsend’s warblers are excitedly singing as they now realize they have a nest full of chicks they need to feed. As the last eggs begin hatching the earlier hatched nestlings begin their cries for food. Both parents leave the nest, returning momentarily to feed the young.

June 11

Hard to believe that only 10 days later the newly hatched chicks are grown enough to begin fledging. Many have undergone their pre-juvenile molt and have shed most of their natal down. By the end of summer, they are expected to complete their performative molt and will begin to resemble their parents (nature instruct, n.d.). The young warblers will keep their yellow throats and soft brown and yellow colouration until they return to their wintering grounds where they will undergo their first prealternate molt cycle (Jackson et al., 1992).

Immature Townsend’s warbler. Photographer: Donna Pomeroy October 4, 2018. Macaulay Library https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/117437181

August 15

It has been a while since I last wrote about my Townsend’s warbler friends. The summer has been spent watching the newly developed juveniles learn to sing and eat on their own. They have learned the two categories of songs from their parents and other nearby adults. Now the young Townsend’s warblers are beginning the next phase of song development, sub-song. It is expected that they will continue to learn and refine their Type 2 song during the long migration back to Mexico in the fall (Janes, 2017). Hopefully the songs will be fully crystallized over the winter so that they may have success at breeding when they return next year.

September 3

As fall fast approaches, the warblers have been busying themselves in preparation for the fall migration back to Mexico. Each individual, young and old, will need to enter a stage of hyperphagia as they store enough fat to meet the energy demands of such a long trip back south (Holzschuh & Deutschlander, 2016). I would like to thank the Townsend’s warbler flock for allowing me to bear witness to their precious lifecycle this past summer and I cannot wait for them to return next spring!

Townsend’s warbler. Photographer: Alice Sun. May 18, 2017 Macauley Library. https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/59037111

References

Audubon. (n.d.). Townsend’s warbler. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/townsends-warbler

All About Birds Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Townsend’s warbler overview. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Townsends_Warbler/overview

Holzschuh, J. A., & Deutschlander, M. E. (2016). Do migratory warblers carry excess fuel reserves during migration for insurance or for breeding purposes? Ornithology, 133(3), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1642/auk-15-141.1

Jackson, W. M., Wood, C. S., & Rohwer, S. (1992). Age-Specific Plumage Characters and Annual Molt Schedules of Hermit Warblers and Townsend’s Warblers. Ornithological Applications, 94(2), 490–501. https://doi.org/10.2307/1369221

Janes, S. W. (2017). Use of Two Song Types by Townsend’s Warblers (Setophaga townsendi) in Migration. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 129(4), 859–862. https://doi.org/10.1676/16-040.1

Krosby, M., & Rohwer, S. (2010). Ongoing Movement of the Hermit Warbler X Townsend’s Warbler Hybrid Zone. PLoS ONE, 5(11), e14164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014164

Morrison, M. L. (1983). Analysis of Geographic Variation in the Townsend’s Warbler. Ornithological Applications, 85(4), 385. https://doi.org/10.2307/1367976

Morse, D. H. (1991). Song types of black-throated green warblers on migration. The Wilson Bulletin, 103(1), 93-96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4162972

Nature Instruct. (n.d.). Browse project: Piranga. Nature Instruct. https://www.natureinstruct.org/piranga/browse?projectId=1&id=9FFEDE99DC82DD92

Pearson, S. F., & Rohwer, S. (1998). Influence of Breeding Phenology and Clutch Size on Hybridization between Hermit and Townsend’s Warblers. Ornithology, 115(3), 739–745. https://doi.org/10.2307/4089421

I love the style of this blog post, Chelsey! I totally imagined you as an old-school field biologist.

I’m curious which song Type (I or II) corresponds with which sound clip you posted (first or second)?

Also, given that climate change is expected to alter certain species’ ranges, how do you expect the Townsend Warbler to respond? Do you think their ranges will expand, contract, shift? Do you think all of their range types will be affected?

Thanks for the fun post 🙂

Hi Thank you for your comment. To answer your question about the Type 1 and 2 songs sung by the Townsend’s Warbler I am actually unsure of which one is which in the audio recordings. I was unable to locate audio examples of these two types of songs, but the first recording was recorded near the warblers breeding grounds so I would think that one would be akin to the Type 1 song.

As for your next question regarding climate change and the effects on the Townsend’s warblers ranges, the Townsend’s warblers are currently undergoing a range expansion in the mountain ranges of Oregon and Washington state. This area is a range overlap between Townsend’s warblers and Hermit warblers and researchers are seeing this zone as a hybrid zone between the two species. They are able to breed with one another and produce viable hybrid offspring. Some of the papers I researched throughout the writing of this blog post lead me to believe that because the Townsend’s warbler is the more dominant of the two species we can reasonably expect that they will eventually completely take over the hybrid range and push the Hermit warblers further south or closer to the coast.

So weird that my first comment went anonymous….IT’S FROM ME!

I loved your unique style of blog post! It kept me engaged and feeling as though I was doing the expedition with you!

I am also curious like the previous comment about the Type I and Type II songs you mention, and I’m wondering if there is a reason/benefit as to why they have a song for migration and then a different one for approaching breeding grounds?

Thanks for a fantastic read!

Hi Emily,

Thanks for the lovely comment about my blog!

To answer your question about why they would have the need to have two different types of songs for migration vs. breeding, I think it would benefit them to communicate different things during these two life stages. When the birds are migrating the songs would communicate position so they don’t get separated along with other information like food and predator sightings. Versus once they get to the breeding grounds they would want to sing a song to establish a territory to attract potential mates and keep out intruders. The two different types of songs would be effective at communicating different messages during these two very different life stages the birds are experiencing.

I really liked the framing device for this blog! Do you have any idea why the female Townsend’s warblers are later to arrive than the males? How much longer do they take to get to the breeding grounds?

Hi Issac, Thanks for the comment on my blog. The males arrive early to establish a territory in the breeding grounds before the females arrive. That way the “best” males can defend the better territories and impress the females once they arrive. The females are trailing behind by a few days to a week.

Hi Chelsey!

Great post. I was wondering if Townsend’s Warblers display pair-bonding throughout the season, and if so, would they stay pairs or, switch for next season?

Isabella

Hi Isabella,

Thanks for your comment. Yes they display pair-bonding throughout the season and are considered monogamous for the season BUT they have been observed with at least 3 additional males hanging around newly paired females which does suggest some degree of extra pair mating is occurring.