Imagine you are a small tern species flying over the Caribbean Sea bringing a fish back to your chick who is resting in a mixed colony of sea birds. You land on a sandy island and make your way to your hungry begging chick, when a shadow blocks the sunlight. You turn and suddenly the fish has been ripped from your beak. You try to take the fish back, but it is too late, your opponent is larger than you and you don’t stand a chance against him. The pirate thief is your neighbour, the Caspian Tern.

Taxonomy

Hydroprogne caspia

Class Aves

Order Charadriiformes

Family Laridae

Identification

Caspian Terns can best be identified by their thick bright-red bill, often with a dark marking at the tip of the bill, and their dark wingtips (Stockwell et al., 2022). Adults have a white body with light grey wings. During breeding they have a solid black cap and during non-breeding the cap is more subdued with light black streaking(eBird). Juveniles have less sharp colours and have V-shaped marking on their wings.

The Caspian Tern can be distinguished from the similar Royal Tern who is slightly smaller, has a forked tail and has a thinner bill that is more orange with no dark marking at the end (eBird).

Caspian Terns are the largest terns in the world and are about the size of an American Crow (All About Birds). They have sexually monochromatic plumage, meaning the males and females look the same, but the males have been shown to have longer head and bill length (Ackerman et al., 2008).

The Caspian Tern’s call is a loud raspy “scream” that sounds like a gull with a frog in its throat (eBird). It is mildly unpleasant, so you have been warned.

Food and Feeding Behaviour

Caspian Terns mainly feed on fish such as chum, coho, chinook, and sockeye salmon, steelhead, Pacific sardine, rock bass, and many more(All About Birds). Crustaceans such as crayfish, large insects, and the young of other bird species are on the menu occasionally as well.

To find their food Caspian Terns will fly between 10 and 100 feet above the water with their bill pointed downward, scanning the water (All About Birds). When they see a tasty meal, they dive at the unsuspecting prey, grabbing it with their large bill under the water. After quickly leaving the water, they will either swallow the fish instantly or carry it to their mate or chick.

Sometimes the pirate Caspian Tern will display kleptoparasitism which is when an individual steals food from another bird (All About Birds).

Caspian Terns require abundant populations of fish and clear waters so they are good indicators of the health of an ecosystem (Birdbot, n.d.). They play an important role in their ecosystem as a top predator, and help maintain healthy aquatic life.

Habitat and Distribution

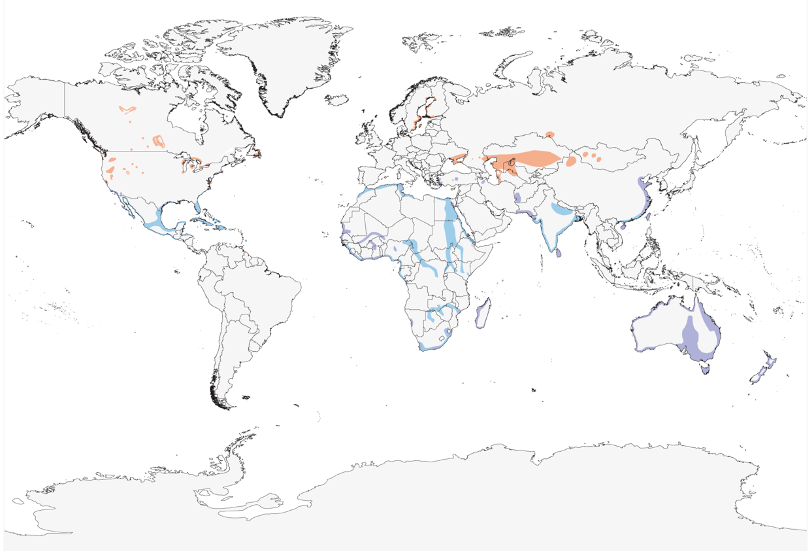

Caspian Terns can be seen on every continent apart from Antarctica (Boyd, 2015). They like to remain near water including marine, brackish, and freshwater environments, and they are happy in both urban areas or more undisturbed environments (Stockwell et al., 2022). In North America their breeding distribution is widespread, breeding in colonies inland surrounding lakes or rivers and along both the west and east coasts (Boyd, 2015). They also breed in areas of Europe and largely in Kazakhstan, many breeding around their namesake, the Caspian Sea. They have a wide overwinter range as well, with many populations in Africa and around the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea (All About Birds). Populations in Australia tend to stick to what they know and do not migrate, but rather undergo shorter movements from tight breeding colonies to less crammed foraging sites (Stockwell, 2022).

Nesting Behaviour

A male Caspian Tern will perform courtship displays by flying back and forth with a fish in his bill. He will land next to the female and present the fish while nodding (All About Birds). If the female likes his dance, she will accept the fish and perform a little dance of her own hunching down and then jerking her bill upwards. When the Caspian Terns have paired up they perform courtship flights over the colony breeding grounds.

Caspian Terns prefer to nest in breeding colonies in open areas close to water with little vegetation and are frequently nesting alongside other gull and tern species (Boyd, 2015). They nest in what is called a scrape nest. This is a depression in the ground that may or may not have lining material added to it (Reid et al., 2002).

The male and female pair will select a site together and make a scrape in an open area with little vegetation (All About Birds). The couple might line the scrape with dried vegetation and surround it with pebbles, shell fragments, sticks, or other objects found close by.

The female will generally lay 1-3 eggs once a year and incubate the eggs for 25-28 days with the males help (All About Birds). Once hatched the young will only stay in the nest for 1-2 days, as they come out of the eggs wide-eyed with a full down coat ready to take on the world. Both parents will play a role in egg incubation, feeding the chick, and defending the nest (Stockwell et al., 2022).

Interesting Facts

- Female-female Caspian Tern breeding pairs have been observed in many locations in the United States, creating what is called a supernormal clutch (Conover, 1983). The two females will both lay their eggs in the same nest and share the task of protecting and raising their young, the same way a male-female pair would.

- The oldest known Caspian Tern was an individual that had been banded in 1986 in Michigan, and found again in 2018 in Illinois, making it 32 years old (All About Birds). This is an amazing age considering the average lifespan of Caspian Terns in the Great Lakes is estimated to be 12 years.

- Caspian Terns are vicious defenders of their territory and nest and have been known to dive bomb humans that get too close (All About Birds; Birdbot).

Conservation Status

The Caspian Tern is a difficult species to observe as they are often in remote locations that are not easy for human access (All About Birds). It is believed that their populations have remained stable from best estimates by the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

In 2012 the Caspian Tern was deemed to be of least concern by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) (Government of Canada, 2015). In Canada their populations appear to be secure but are a priority for conservation as they face many threats from human disturbance and contaminants through biomagnification.

Since the early 1900s Caspian Tern numbers have increased in North America likely because of human created habitats and protection put in place for individual birds and breeding colonies (Boyd, 2015).

Current Research: Caspian Tern Management to Increase Survival of Juvenile Salmonids in the Columbia River Basin

In a study done by Collis et al., Caspian Terns were relocated to reduce their predation on young salmonids (salmon and trout), called smolt (2024).

One of the Pacific Northwest’s most important natural resource industries is the fish industry, but many of these fish are listed as threatened or endangered. One method to support the reducing populations of smolt is the management of avian predators. This is a controversial approach as some believe the root causes of salmonid declines should be addressed instead (habitat loss, among other things), but others believe the avian predators have a large enough effect they should be addressed instead.

Caspian Terns’ predation on smolt have been deemed to be factor affecting the recovery of some salmonid populations in the Columbia River basin, but not the leading cause. This led to two separate management plans to reduce Caspian Tern impacts on smolt in the Columbia River Basin, one in the Columbia River estuary and one in the Columbia Plateau region. Caspian Terns were relocated from their breeding colonies in the basin to alternative nesting islands created specifically for the terns’ preferred nesting habitat. Avoiding putting the tern population at risk was an important consideration in this management plan.

These plans were both successful in that smolt losses were significantly reduced in the sites of interest. However, many terns were shown to return to the original managed sites they were removed from. This is expected because these sites are very attractive to the Caspian Tern. To keep the terns from returning to the managed sites continued management will be necessary. Adaptive management is needed to be sure the Caspian Tern is not negatively affected in these management plans.

Thank you for taking the time to read about the pesky, but strong and beautiful Caspian Tern. Please feel free to leave a comment or question if you have one!

References

Ackerman, J. T., Takekawa, J. Y., Bluso, J. D., Yee, J. L., & Eagles-Smith, C. A. (2008). Gender identification of Caspian Terns using external morphology and discriminant function analysis. Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 120(2), 378–383. https://doi.org/10.1676/07-061.1

Audubon. (n.d.). Caspian Tern. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/caspian-tern

Birdbot. (n.d.). Caspian tern. BirdBot – Making Birding Accessible to Everyone. Retrieved November 1, 2024, from https://www.bird.bot/guide/caspian-tern

Boyd, M. (2015). Caspian Tern in Davidson. The Atlas of the Breeding Birds of British Columbia, 2008-2012. Bird Studies Canada. Delta, B.C. Retreived October 30, 2024, from http://www.birdatlas.bc.ca/accounts/speciesaccount.jsp?sp=CATE&lang=en

Collis, K., Roby, D. D., Evans, A. F., Lawes, T. J., & Lyons, D. E. (2024). Caspian Tern Management to Increase Survival of Juvenile Salmonids in the Columbia River Basin: Progress and Adaptive Management Considerations. Fisheries, 49(2), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsh.11012

Conover, M. R. (1983). Female-Female Pairings in Caspian Terns. The Condor, 85(3), 346. https://doi.org/10.2307/1367073

All About Birds. (n.d.). Caspian Tern. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved October 28, 2024, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Caspian_Tern/lifehistory#habitat

eBird. (n.d.). Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved October 25, 2024, from https://ebird.org/species/caster1

Government of Canada. (2015). Summary statistics, Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia). Retreived October 30, 2024, from https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/oiseau-bird-eng.aspx?sY=2014&sL=e&sM=p1&sB=CATE#ref742

Northwest Power and Conservation Council. (2024). Predation by Caspian Terns. Predation by Caspian terns. https://www.nwcouncil.org/fish-and-wildlife/issues/predation/birds/terns/

Reid, J. M., Cresswell, W., Holt, S., Mellanby, R. J., Whitfield, D. P., & Ruxton, G. D. (2002). Nest scrape design and clutch heat loss in Pectoral Sandpipers (Calidris melanotos). Functional Ecology, 16(3), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00632.x

Stockwell, S., Greenwell, C. N., Dunlop, J. N., & Loneragan, N. R. (2022). Distribution and foraging by non-breeding Caspian Terns on a large temperate estuary of south-western Australia-preliminary investigations. Pacific Conservation Biology, 28(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC20082

Vehanen, T., Sutela, T., & Huusko, A. (2023, July 1). Potential Impact of Climate Change on Salmonid Smolt Ecology. Fishes. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8070382

Great blog! A really interesting bird. You said that the young leave the nest 1-2 days after hatching, which made me want to ask, how soon are they able to fly? And if they can’t fly right away, what do they go during that time?

Thank you Emma, great question! The Caspian Tern chicks are not able to fly until about 4-5 weeks after hatching, but they hatch fully covered in feathers and are able to walk around. Leaving the nest and moving closer to the waters edge is often more beneficial for the young so they are not vulnerable “sitting ducks” to predators. While they are unable to fly the juveniles will wait near the shore for their parent to return with food, often guarded by the other parent. Some individuals will remain in the nest if undisturbed but this is rare. After fledging and leaving the breeding grounds the juveniles will often continue to be fed by their parents in their wintering grounds for up to 7 months after fledging.

Great blog Bekah! I really had no prior knowledge about Caspian Terns before reading it! Including a bit of humor and simple terms, I found this blog enjoyable and easy to read and understand.

I do have a couple questions – you had mentioned both males and female cooperate in raising offspring. Do you know if males or females (or neither) generally arrive first at their breeding grounds? And do both or just one sex build their nests?

Thanks,

Eric

Thank you for the Question Eric! Both the male and the female build the nest together after choosing the nest site together. I was unable to find information about if the males and females arrive at the breeding grounds at different times but I did find information saying they will often arrive in large flocks. This would lead me to believe that the males and females arrive at the same time. Sometimes male and female Caspian Terns arrive at the breeding sites already paired so in this case they would arrive at the same time.

Great post, Bekah! Are their breeding grounds in Canada protected at all?

Thank you! Yes Caspian Terns breeding grounds are protected in Canada. There are a number of regions where the species are listed as a priority in bird conservation by the Canadian government.