by Doris Carey, Faculty Member, Faculty of Academic and Career Preparation, VIU

In my decades as an educator, few students have ever claimed that their preferred learning modality is auditory. Not that it matters, since no research evidence exists to support the widely held belief that students learn best when their preferred modality is accommodated. Most students claim they are visual learners. If I assign homework, they insist that I give them the assignment in writing on the board. They prefer sketches, drawings and pictures to lists of words. However, if left alone with a textbook and a density of words in a paragraph, they prefer a verbal explanation from the teacher, accompanied by examples written on the board or overhead transparency.

All of this information comes to the fore when I think of optimal learning conditions and the much-touted death of the lecture format in schools and universities. Following the utter failure of MOOCs (free Massive Open Online Courses), I’m always interested in how technology claims in the area of mathematics instruction pan out. I read a few blogs about math ed and technology that purport to throw out the lecture format and let students use video technology at home to watch the instruction. They allegedly use class time for questions and one-on-one tutoring by the teacher.

I’ve heard many students and colleagues swear by the video instruction available for everyone who has internet access. I can’t help rolling my eyes when I observe these videos. They’re nothing more than video of the white board on which an instructor is scribbling while a voice-over lecture explains what’s being viewed. The only difference is that no one stops the lecturer to pose questions. It’s a faster version of what I do since the instructor can zip through a lesson in 20 minutes or less. No interruptions, no questions. And if that went by too quickly, the viewer can replay the tape. You can’t rewind my classroom lesson, but you can ask me to explain the concept again, and I’ll find a new way to explain, with new examples and even some new words that might work better. You can’t do that with the video.

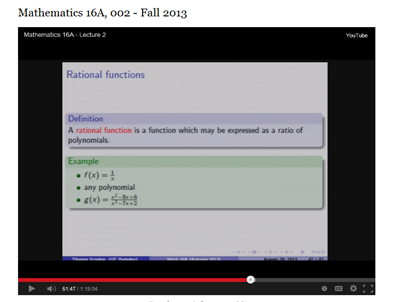

The picture below shows a screen shot from a MOOC offered from UC Berkeley. It’s basically a textbook page with a voiceover, taped for YouTube and interspersed with video of the instructor’s hands drawing a crude sketch.

It’s possible that students pay closer attention to a video because they know it’s all they’re going to get. They can rewind, but they’ll see the same thing again. It’s possible that they’re more fully engaged because they have ultimate control. If they feel sleepy, they can come back after they’ve had a nap and an energy drink. If they’re bored, they can pause the tape. My gig isn’t available day or night. They show up for the scheduled time or they miss out. That’s less than optimal.

So it isn’t the lecture format per se that isn’t effective for my so-called visual or auditory learners. It’s probably the control (in the guise of flexibility, which it totally lacks) and the convenience. I can’t argue with those benefits.

In my dream of the perfect world for math education, students could individually view all of the routine content of a course in the comfort of their own homes, complete with the benefits of rewinding, naps and snack breaks. But it would be a superior videotaped lesson, complete with real-life applications outside the lecture hall. It would allow branching to an alternative presentation of the same content, emulating what effective teachers actually do in class. The video would engage students and walk them through sample problems.

With that preparation done, students can then come to my classroom for help with assignments, discussion of projects, exposure to other students’ findings and solutions, and formative assessment that provides thorough feedback. Meanwhile, I’m satisfied to know that today’s cutting edge technology isn’t ready to replace me.