The Fantastic or Mythical is a Mode available at all ages for some readers; for others, at none. At all ages, if it is well used by the author and meets the right reader, it has the same power: to generalise while remaining concrete, to present in palpable form not concepts or even experiences but whole classes of experience, and to throw off irrelevancies.

– C.S. Lewis,

“Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to be Said”

One of the defining aspects of C.S. Lewis’ fictional work, especially demonstrated in the popular novels that comprise the Chronicles of Narnia, is Lewis’ incorporation of highly moralizing Christian imagery and what many scholars view as Lewis’ consistent use of Christian allegory. Understood largely as apologetic fiction, and perhaps in large part due to their popularity, the Chronicles of Narnia represent a significant intersection between Christian idealism and the underlying functions associated with children’s literature. Didacticism and moralization are not new concepts as they pertain to children’s lit – perhaps even as much so when viewed in relation to the traditional, western fairy tale or the Aesopian moral fable – however, and in light of modern criticism, the underlying function of Lewis’ work reveals itself as being largely problematic when considered in relation to the normativities that it often seeks to reinforce.

This is particularly true when concerning Lewis’ heteronormative standard, highly distinguished gender associations and his overwhelmingly antiquated depictions of sterotypified Middle-Eastern culture. In a 1998 publication of The Guardian, Phillip Pullman – author of His Dark Material, and in many ways a competitor to Lewis’ fantasy-fiction – stated that there was “no doubt in [his] mind” that the Narnia series was “one of the most ugly and poisonous things [he’d] ever read” (Pullman, “The Dark Side of Narnia”). Though arguably hyperbolic, the predicate for Pullman’s criticism is focused on the discord he sees between the popularity of the novels, their pedagogic function as novels designed for children, and the culturally insensitive normativities that the novels endorse. Based largely on the same problematizations observed here and as emphatic as it might appear, Pullman’s condemnation of Lewis’ texts on the basis of their “misogyny”, “racism”, “supernaturalism” and “sheer dishonesty” (ibid) is, perhaps unfortunately, more or less grounded in what amounts to valid critique.

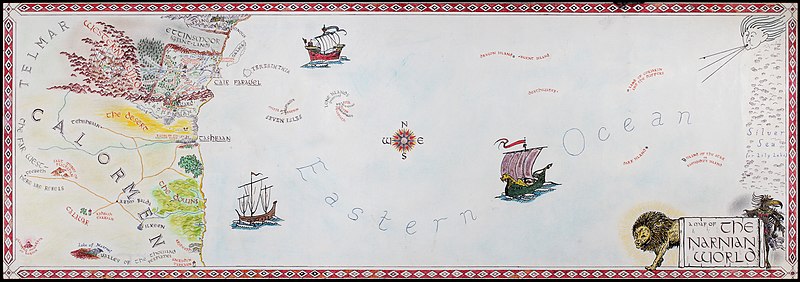

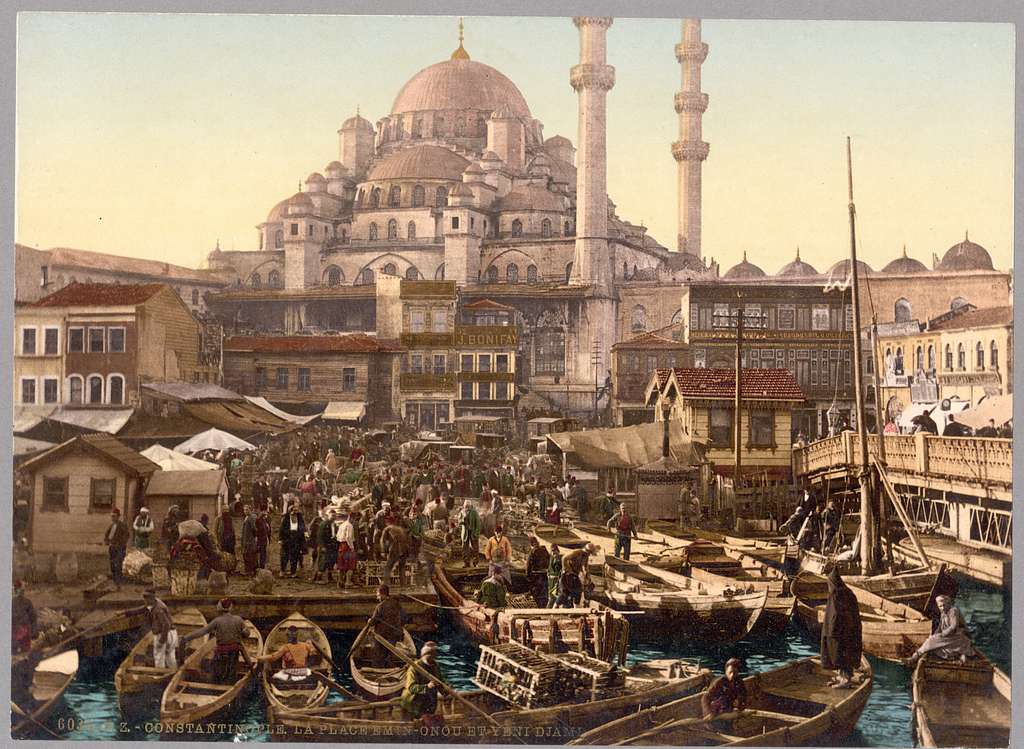

For many readers, including those fans that have been familiarized with the Narnian stories at a young age, this can be a difficult thing to acknowledge. In recognizing this, and while not seeking to endorse Pullman’s language, this paper will provide as impartial an analysis as possible as to the problematization inherent in Lewis’ work. In the interests of length, this analysis will focus exclusively on Lewis’ novel, The Horse and His Boy and will observe how Lewis’ incorporation of Christian symbolism reinforces problematic, ethical standards. Regarding The Horse and His Boy, this standard is made more apparent when viewed alongside Lewis’ highly stereotypical rendition of Calormen (a fictional nation reminiscent of Turkey and the Ottoman Empire) and his characterizations of Calormene culture. However, and besides this, the underlying problem inherent within this text concerns its central plot – which maintains loose characteristics reminiscent of a biblical exodus – and the imaginative geographies that inform the novel’s plot movement.

In order to better understand these characteristics, it can be insightful to examine The Horse and His Boy (hereafter abbreviated: TH&HB) within the emerging contexts of post-theory and children’s literature. In her article, “Theory, Post-Theory, and Aetonormative Theory”, Maria Nikolajeva proposes “a heterological approach to juvenile literature” that “examines the power balance between the adult author and the implied young audience” on the basis of what she refers to as “aetonormativity (Lat. aeto-, pertaining to age)” (16). She argues that “adult normativity… governs the way [that] children’s literature has been patterned from its emergence until the present day” and “is most tangibly manifested in the relationship between the ostensibly adult narrative voice and the child focalizing character” (ibid). In a manner of speaking, the adult-author utilizes a focused, child-character as a means of furthering a relationship between their narrative voice and the attitudes of the juvenile reader that the authorship seeks to affect. In essence, this situates the child-character as a literary device, or even an instructional tool with which the author can impress a standard upon their predominantly child-readership.

One such example in TH&HB occurs on p.36, and “reveals the degree of alterity” (Nikolajeva, 16) imposed by the narrative voice upon cultural practices and the oral tradition. The text reads:

…in Calormen, storytelling (whether true or made up) is a thing you’re taught, just as English boys and girls are taught essay writing. The difference is that people want to hear the stories, whereas I never heard of anyone who wanted to read the essays (Lewis 36).

The problem with this passage isn’t so much that it reinforces negativity, but is instead centered upon the author’s narrational voice (demonstrated by the narrator’s use of ‘I’) and its separation of Calormen storytelling from that which is familiar to ‘English boys and girls’. Not only is there a distinguished, cultural division in the language used, but there is an implied emphasis that the difference in question specifically concerns English children. Because of this distinction, while the narrative-voice is attempting to impart a lesson regarding oral vs. written traditions, it simultaneously reinforces this distinction by means of delineating English practices away from or against those that are determinately ‘other’. While in this passage a distinction like this might be considered relatively benign – especially considering that the narrator almost seems to endorse oral storytelling above written forms – it does however demonstrate a relationship that fundamentally defines the novel.

1890. Picryl, (accessed 6 Dec 2021), https://picryl.com/media/yeni-cami-mosque-and-eminonu-bazaar-constantinople-turkey. Licensed under CC0-1.0.

In TH&HB, this relationship is illustrated literally through the physical layout of the Narnian geography. While many of the novels depict overtly mythological or fantasy oriented settings, and frame these representations through Narnia as an idyllic and enriched locale, TH&HB utilizes a setting that is both deprived of these mythological characteristics and that is modeled as a foreign and ‘Orientalized’ state. In her article “Representations of Home, the Orient and the Other “Other” in Selected Children’s Fantasy Literature” Farah Ismail observes this geography in light of post-colonial theory and orientalism, based primarily upon the research of Edward Said. She argues that “Calormen’s function in the narrative is to act as the moral contrast to Narnia” and identifies Calormen’s role as a Saidian “imaginative geography” on two principle bases: “first,” that it is represented “as a fictional, imagined space and secondly, as a collection of ideas figured as a contrasting Other, which is used to define Western subjectivity” (Ismail 6). From Ismail’s perspective, Calormen doesn’t represent a precise rendition of an eastern or “Other identity” – meaning that its use in the story has nothing to do with multiculturalism or cultural representation – but is instead defined entirely “by its use as a contrasting Other” (ibid). Which is to say that it is a depiction of an exoticized sphere that is not only rendered through a western purview, or subjectivity, but that its sole purpose is to provide an antithesis to the anglicized spheres that the narrative seeks to idealize.

To this effect, and as Ismail notes, by rendering Calromen as “an Oriental imaginative geography in his depiction of Calormen,” Lewis essentially instantiates “the Other-space as inferior” to those of Narnia or “Archenland, a country which is culturally indistinguishable from Narnia and, like Narnia, embodies” a superlative and “idealised space” (7). This dynamic is punctuated by the fact that Calormen is a setting that is deprived of mythological characteristics and “in which there are no magic or fairy tale creatures” (6). Moreover, Ismail argues that the conscious “absence of the magical, the mythical and all elements that inspire wonder” is in fact an intentional tool that “signals the lack of spiritual enrichment” in non-westernized settings (ibid). Meaning that for a young reader, the normativity being reinforced is the unconscious association of mystical elements with ethno-culturally familiar settings – often denoted by skin color and clothing, as well as fantasy characteristics – against the perhaps more conscious associations that Lewis attaches to a Calormen, imaginative geography.

This dynamic is established almost immediately within the narrative, and once again Lewis employs Shasta (later, Cor) as a focalizing character in order to demonstrate this distinction. From the onset, Shasta is depicted as being “not at all interested in anything that lay south of his home because he had once or twice been to the village… and he knew that there was nothing very interesting there”, while conversely, “he was very interested in everything that lay to the North because no one ever went that way and he was never allowed to go there himself” (Lewis 2). The fact that this dynamic is established so quickly within the narrative exposes the underlying prerogative that informs the plot. Shasta’s imperative is strictly directional – always north, never south, and always away from the sense of entrapment attached to sterotypified Calormen settings. In light “of the Orientalist imaginative geographies of east and west” suggested by scholars like Ismail and Said, in TH&HB this geography “both spatially and ideologically contrasts Calormen and Narnia by demarcating one space as the ‘south’ and one as the “North’” – maintaining that ‘north’ “is always capitalised… and loading these terms with significance” (Ismail 9).

“It was I who wounded you,” said Aslan. “I am the only lion you met in all your journeyings. Do you know why I tore you?”

“No, sir.”

“The scratches on your back, tear for tear, throb for throb, blood for blood, were equal to the stripes laid on the back of your stepmother’s slave because of the drugged sleep that you cast upon her. You needed to know what it felt like.”

Lewis, TH&HB p. 216

Beyond spatial relationships, Lewis is also quite guilty of utilizing almost transparent stereotypification. “Scimitars, turbans, stylized beards, and minarets call to mind the medieval Islamic world, as does the ever-present image of the crescent” (Howe 91) and the near 1:1 comparison illustrated by Lewis provokes the modern reader into an immediately critical stance when concerning his method of racialization. As Andrew Howe observes in his article “The Latest Battle: Depictions of the Calormen in The Chronicles of Narnia”, Calromene characters are almost always characterized, first and foremost, by cruelty and coercion – even to the extent where these characterizations cross class and gender boundaries. He states that:

From Shasta’s abusive adoptive father, Arsheesh, to Bree’s cruel owner to the cold calculation of the Tisroc, Calormene characters in this book are portrayed as fallen and generally beyond redemption, be they laborer or King. Even one of the protagonists, the princess Aravis, is corrupted by her time in Calormen and must be re-programmed in order to be acceptable in the more civilized, northerly countries of Narnia and Archenland. (92)

In particular, the character of Aravis is especially interesting when considering cultural associations. Arguably, and as one of the central protagonists within the story, she represents the only Calormene character with any redeemable qualities. What’s more, is that she is one of the few characters in the whole of Lewis’ Chronicles that reflects any degree of intersectionality.

As both a woman and a Calormene, she “is able to break free from the stifling gender structures that threaten to overwhelm her” (94), however, it is not without note that Lewis portrays her as relying on “trickery in order to escape her situation” (ibid) and is punished in a manner deemed as ‘proportionate’ to this result (Lewis 154; 216). Again, of all the characters within Lewis’ Chronicles, Aravis is the only protagonist to be physically harmed by Aslan in order to impart a moral lesson, and the circumstances attached to these sequences are uniquely violent when compared to those involved with any of the other Narnian children. Deemed as “equal to the stripes laid on the back of [her] stepmother’s slave”, the connotation attached to the phrasing: “tear for tear, throb for throb, blood for blood” (216) stands apart as being discernibly graphic when considering the status of these texts as children’s novels.

What’s more, is that in order to effectively resolve the novel’s plot conflict, Lewis consciously objectifies Aravis into that of a marriage-article – “coerced into betrothal, as if she were a piece of property” (Howe 94) – and demonstrates a transition denoted as much by a change of clothing (Lewis 229) as it is by a relinquishment of Aravis’ cultural identity. In fact, and as specified by Andrew Howe, for the majority of the narrative Aravis as a character is almost completely deprived of agency, and upon the story’s conclusion, “becomes a background character, marginalized not only by her gender… but also due to her racial status as a Calormen” (94).

“I was the lion who forced you to join with Aravis. I was the cat who comforted you among the houses of the dead. I was the lion who drove the jackals from you while you slept. I was the lion who gave the Horses the new strength of fear for the last mile…. And I was the lion you do not remember who pushed the boat in which you lay, a child near death, so that it came to shore where a man sat, wakeful at midnight, to receive you.”

Lewis, TH&HB p. 176

Pursuant to understanding the significance of this conclusion, it is important to view TH&HB within its biblical and intertextual contexts. One of the defining intertextual aspects of this novel has much to do with its portrayal of Shasta and Aravis’ journey out of Calormen as a form of spiritual exodus. Traditionally speaking, the “exodus is the story of the birth of a people, a social and ethnic unity, that emerges in Israel beginning in the Iron Age”(Hendel 621) and is a central narrative when concerning both the Christian old testament, and the Jewish Pentateuch. Ronald Hendel, in his article “The Exodus in Biblical Memory” suggests that the exodus story is predominantly concerned with the collective memory of the Israelite peoples, and that it fundamentally elicits themes of self-determination, and the establishment of a Jewish ethno-cultural identity. He argues that: “The story as a whole defines the collective identity and ethnic boundaries of the people, providing a common foundation for social and religious life” and that the “[t]he processes of ethnic self-definition are evident in the symbolic rites of passage” that distinguish Judaism and Jewish peoples as being culturally and religiously distinct in an area that is notably multicultural and that informs a number of religious belief systems (621).

Strangely, and while considering this affect, the exodus interpolations which take place in the TH&HB seem to reflect this function. Mentioned prior, and again in her article “Representations of Home, the Orient and the Other “Other” in Selected Children’s Fantasy Literature”, Farah Israil notes that “as the first of The chronicles to prominently feature Calormen, it is significant that… this is the one that deals most explicitly with themes of identity and home” (7). Much like the exodus story, TH&HB also concerns itself with cultural identity and a movement of self-determination – however, whereas the exodus story focuses on an ethno-cultural minority, especially as a piece of scripture that sustains the collective memory of an entire Jewish diaspora, TH&HB adversely, and once again in many ways unfortunately, seeks to assert a sense of Anglo-Christian identity directly against that of a sterotypified rendition of a pre-existing, and equally as distinct culture.

Concerning direct, intertextual reference, and aside from the geographical movements that take place in the story, there are two allusions that discernibly link TH&HB with the exodus story, however, in the interests of length this paper will focus exclusively upon the more pertinent example. As an allusion, exodus intertextuality in TH&HB is immediately evident within Lewis’ incorporation of the “‘lost child’ motif” (Ismail 7). This trope situates Shasta alongside Moses as a character with a divided identity (Lewis 6-7; 217-223) and the plot movement as one that moves away from the first – be it Shasta as fishermen’s son, or Moses as the adopted son of a pharaoh (NRSV Bible, Exodus 2:1-10) – and into the determination of another. “In this way,” and much like Moses, “Shasta comes to fulfil the prophecy that was made at his birth, and saves Archenland by warning the kings of Archenland and Narnia of the invading Calormene army” (Ismail 7). However, and again like Moses, this transformation and eventual outcome is facilitated by “the journey [of] fleeing one identity (as Shasta of Calormen) to discovering another (as Cor of Archenland)” (ibid). What this reinforces, and if by now the problematization inherent with this dynamic wasn’t readily apparent, is that in order for Shasta as a character to satisfy his prophetic birthright, he must simultaneously reject his identity as a Calormen and journey away from settings with which that identity is inexorably attached.

In understanding this dynamic, it becomes clear that Aravis’ journey and eventual marriage is placed at a parallel with Cor’s (Shasta’s) and indicates that in order to adopt the overtly Christian moralities that Lewis holds as paramount, a character must simultaneously exercise repentance – in the form of an almost ritualized clawing received from Aslan – and abandon the ethno-cultural and even religious identities that the narrative seeks to diminish. Neither Aravis nor Shasta can be accepted into the westernized fold if they maintain the characteristics of a culture that is situated as lesser, and, unlike the exodus story, the underlying plot movement of TH&HB directs this transformation even at the expense of Aravis’ agency and an intrinsic sense of cultural selfhood. In brief summary, not only is this reinforced by intertextuality, but is actually predicated upon the entire geo-cultural structure of the Narnian world and the imaginative geographies that inform its makeup. What’s more, is that these dynamics are also what comprise Lewis’ didactic and ethical standard – which means that their affect as components of a children’s story is to reinforce, and fundamentally impress a flawed normativity upon what are likely highly impressionable readers. And, perhaps understandably, it is this relationship that has provoked criticism, however hostile or damning, from authors such as Phillip Pullman and modern scholarship directed towards Lewis’ material.

Work Cited:

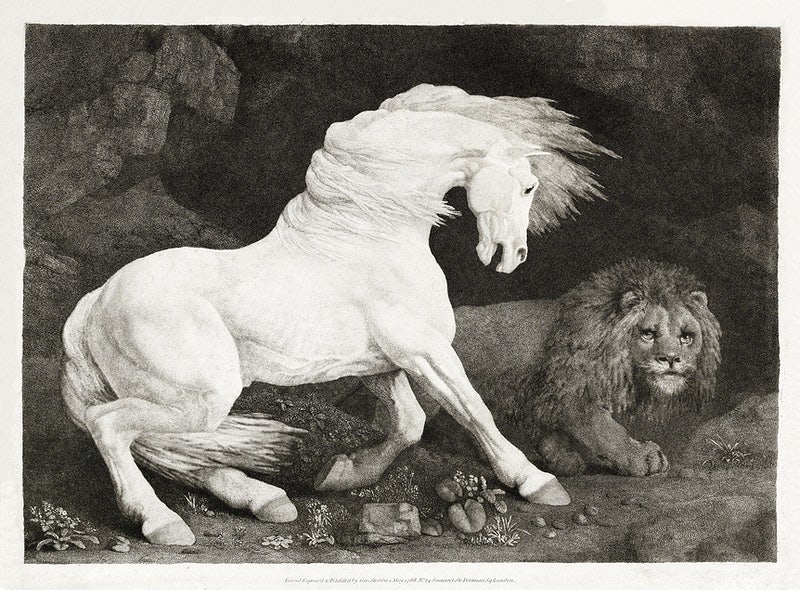

“A Horse Affrighted at a Lion (1788) by George Stubbs. Original from The MET Museum. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.” Rawpixel, (accessed 7 Dec 2021), https://www.rawpixel.com/image/2764683/free-illustration-image-horse-painting-lion. Licensed under CC0 1.0.

Dickieson, Brenton. ““Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to be Said” by C.S. Lewis.” A Pilgrim in Narnia, 21 Oct 2021, https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2014/01/27/sometimes-fairy-stories.

Hendel, Ronald. “The Exodus in Biblical Memory.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 120, no. 4, Society of Biblical Literature, 2001, pp. 601–22, https://doi.org/10.2307/3268262.

Howe, Andrew. “The Latest Battle: Depictions of the Calormen in The Chronicles of Narnia” American, British and Canadian Studies, vol.29, no.1, 2017, pp.84-102. https://doi.org/10.1515/abcsj-2017-0020.

Ismail, Farah. “Representations of Home, the Orient and the Other “Other” in Selected Children’s Fantasy Literature.” Scrutiny 2, vol. 21, no. 1, 2016, pp. 3-17. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1080/18125441.2015.1072838.

New Revised Standard Version. Bible Gateway, www.biblegateway.com. Accessed Dec 3rd 2021.

Nikolajeva, Maria. “Theory, Post-Theory, and Aetonormative Theory.” Neohelicon (Budapest), vol. 36, no. 1, 2009, pp. 13-24. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1007/s11059-009-1002-4.

Orlik, Emil. “Oasis in the Desert.” Wikimedia Commons, 22 Aug. 2019 (accessed 3 Dec. 2021), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emil_Orlik,_Oasis_in_the_Desert,_c.1913,_NGA_153826.jpg. Licensed under CC0 1.0.

Pullman, Phillip. “Portrait: The dark side of Narnia; Why are we marking the centenary of CS Lewis’s birth with parties and competitions? His books were reactionary and dishonest, says Philip Pullman”. The Guardian (London), October 1, 1998. https://advance-lexis-com.ezproxy.viu.ca/document/?pdmfid=1516831&crid=ab52bf69-3052-4bd4-a26b-1b140ebd2ec3&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A3TS8-9S40-0051-451F-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=138620&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=xzvnk&earg=sr0&prid=718aec82-917e-4d13-8347-8844cb6b06f4. Accessed December 3, 2021.

“The Lion and the Horse.” 1777. Picryl, (accessed 7 Dec 2021), https://picryl.com/media/the-lion-and-horse-427e3c. Licensed under CC0 1.0.