Exploring LWW as Apocalyptic Literature

The lion or the lamb? Comparing Jesus’ non-violence in the Gospels and Aslan’s violence in LWW

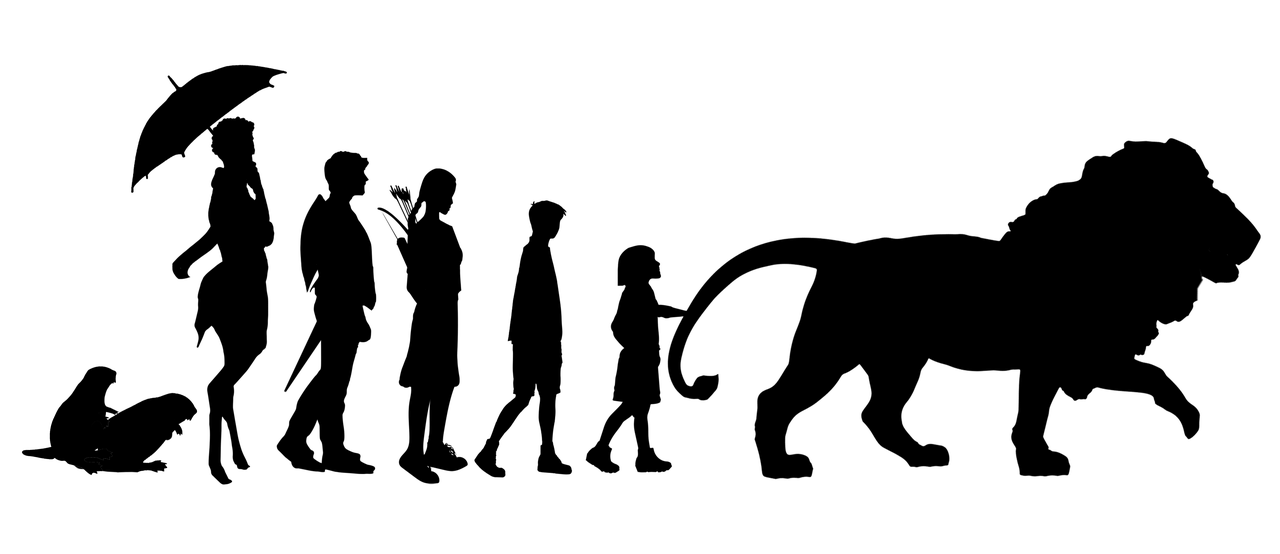

The character of Aslan within C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is a striking allegory to Jesus Christ, especially in The Passion. Both are symbols of rebellion against a sinful oppressor, sacrifice their lives as a form of retaliation, and are given that life back via a deeper power—though the gospel of Mark leaves Jesus’ resurrection uncertain. The two figures do not have the same relationship with violence, however. While Jesus practices and preaches non-violent retaliation, citing divine retribution as the solution, Aslan is a nearly all-powerful being who uses his power as violent means to an end of his oppressor’s reign.

Three distinct representations of this difference are how Aslan and Jesus teach their disciples how to retaliate to violence against themselves, the figures’ resurrections and their actions afterwards, and how divine violence is a concept Jesus defers to, while Aslan embodies it. I’ll be using Matthew’s gospel for most of my discussion because of its concern with violence, although I’ll explore Mark’s version of Jesus’ resurrection, or lack thereof.

Aslan is a nearly all-powerful being who uses his power as violent means to an end of his oppressor’s reign.

When Jesus tells his disciples the laws of the prophets, he dismisses the popular Roman laws such as an “eye for an eye,” saying instead “Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also,” (Matthews 5:38–42). Jesus consistently teaches non-violence to his followers with the expectation God will punish those who have wronged them. Jesus warns that he is sending his disciples “out like sheep into the midst of wolves” and to expect persecution from the religious leaders, and even general public, of the communities they enter. He stresses that whenever his disciples encounter resistance from the public, they should simply move on to the next town as God will not look favourably on that family or community come the day of judgement.

When encountering violent resistance from the governors or kings of that area, Jesus tells his disciples to remain “innocent as doves” and flee to the next town (Matthews 10:5–23). In fact, Jesus’ first act of non-violence—or, rather, Joseph’s—is to flee to Egypt from the murderous Herod, and again to Nazareth from Harod’s son, both looking to harm the infant Christ. Jesus also speaks to his disciples in the Sermon on the Mount, telling them to welcome and be glad of any persecution they receive. If persecution is a result of staying true to God’s teachings and helping the oppressed, God’s gifts in heaven will be great (Reid, “Violent Parables,” 28).

“’For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet only your brothers and sisters, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same?’”

Barbara E. Reid talks about two interpretations of God in the Gospel of Matthew—one forgiving and peaceful, one violent and vengeful (“Which God?” 380). Jesus often threatens divine violence on those that resist his teachings, though always practices non-violence himself and stresses his mortal followers to do the same. Divine violence, however, is painted as a bloody and terrible future for sinners, creating a confusing contradiction with Jesus’ words: “‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ For I have come to call not the righteous but sinners” (Matthew 9:12,13). Jesus insists on helping his enemies more than those already loyal to him, “’For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you greet only your brothers and sisters, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same?’” (Matthew 5:46,47).

Aslan is decidedly pro-violence in his teachings to the Pevensie children—notably Peter. The children and Narnians on the side of Aslan are ambushed shortly after the children meet him for the first time. Peter uses his sword to save Susan from a wolf under the command of the White Witch, ultimately stabbing the animal through the heart and killing it. The scene is quite graphic, as Lewis describes the wolf’s blood covering Peter and its twitches and snarls as it lay dying. Aslan tells the Narnians to hunt down the second wolf fleeing through the woods before turning to Peter saying he has forgotten to clean his bloody blade. Once Peter wipes it on the grass, Aslan takes the sword and knights Peter, dubbing him Sir Peter Wolf’s-Bane.

Aslan reminds him that “whatever happens, never forget to wipe your sword” (Lewis, 120, 121). Now, Peter must save his sister from eminent danger and has no real choice other than fight with his weapon, though there is the question of why Lewis wrote his characters into this scenario in the first place. The favour of violence lies most strongly with Aslan, however. He presumably could have scared off the wolf but chose to let Peter kill it, and with Aslan’s moral authority he decided to respond to Peter’s actions with great praise. Aslan is most interested in his disciples keeping their innocence despite violence—wiping the sword clean. In comparison, Jesus scolds one of his followers who draws his sword and cuts off the ear of a slave of the high priest arresting Jesus, saying “‘Put your sword back into its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword. Do you think that I cannot appeal to my Father, and he will at once send me more than twelve legions of angels? But how then would the scriptures be fulfilled, which say it must happen in this way?” (Matthew 26:52–54). Whereas the Gospels keep the violence of God and the non-violence of Jesus and his disciples separate, Lewis seems to meld them together in somewhat of a contradiction. What is the moral righteousness Aslan is telling Peter to keep by cleaning his sword? It may be an allusion to keeping one’s soul pure and uncorrupted by the “necessary” killing. Jesus’ message is for his followers to ignore the injustices and persecution directed towards them, while Aslan recognizes retaliatory violence as the correct action, though one that must not be dwelled upon.

Carter implies that God’s violent acts have close ties to the Roman empire’s Pax Romana—peace through conquest. In this respect, Aslan’s power can be seen as similar to that of Roman emperors.

Jesus speaks of a sword as well—but instead of rejecting what the weapon symbolizes, he interestingly embraces it. He reminds his disciples that he has not come to bring peace to earth, but to bring a sword to divide the families of the land. Individuals must love him more than they love their own parents, siblings, and children or they are not worthy of him (Matthew 10:34). This is just one of many instances of “sanctioned violence” Jesus alludes to, God being the perpetrator of said violence (Carter, 295). Jesus likening himself to a sword pales in comparison to when he describes the violent divine retribution the world will experience come the end of times. Jesus describes “great suffering, such as has not been from the beginning of the world until now, no, and never will be,” with God’s wrath cut short for the sake of the chosen, or else all would perish (Matthew 24:21,22). The coming of the Son of Man will be like lighting flashing from the east to the west, which Carter says represents the Roman god Jupiter and is Rome’s power turning “against Rome to assert the violent end of its empire and establish God’s empire, (296). Carter implies that God’s violent acts have close ties to the Roman empire’s Pax Romana—peace through conquest. In this respect, Aslan’s power can be seen as similar to that of Roman emperors. God’s retributive violence is often displayed in Matthew. Theoretically, this kind of violence condemns violent acts from mortal followers because divine justice is promised, though this divide isn’t usually maintained in reality and followers take it upon themselves to enact violence (Neville, 134). In this case, the lesson may be that violence in some form always prevails (135). It’s interesting how Jesus is pointedly different than his oppressors in the way he seeks peace non-violently yet is always reminding his followers and enemies of the inevitability of a divine hostile takeover. While we never actually see the divine power Jesus speaks of (arguably until his resurrection) Aslan embodies it, especially after his own resurrection.

The humiliation of Aslan and Jesus before their deaths bear strong resemblance with both figures being violently bound, beaten, mocked, and shamed. They also are both resurrected out of view from any witnesses and Aslan cracks the Stone Table while Jesus tears the temple curtain. What happens after their resurrections, however, is very dissimilar. Aslan rejoices with Lucy and Susan, lets out a fierce roar, and brings back to life all the Narnians turned to stone in the White Witch’s castle. Then the entire group, amounting to a small army, race to the aid of Peter and the rest of the Narnian resistance as they desperately fend off the Witch and her soldiers. The scene is gruesome: the battlefield is dotted with Narnians turned to stone, Peter and the Which duel blade to blade, and “horrible things happening wherever [Lucy] looked” (Lewis, 159,160). Aslan then leaps onto the Witch, killing her (though we’re not clearly shown her death) and the Narnians rallying to kill most of the rest of her army. The Pevensie children are made kings and queens of Narnia and spend time after the battle “seeking out the remnants of the White Witch’s army and destroying them,” with Lewis noting that “in the end all that foul brood was stamped out” (166). Most of the final chapter describes how the new kings and queens make Narnia a safe place again, which seems to be intrinsically linked to violence against the “evil” forces. It’s unclear what Aslan’s role was in this, but it’s remarked that he’ll be there one day and gone the next, as he “has other countries to attend to” and he can’t be pressured into staying (165-166).

While the consequences of Aslan’s resurrection are clearly violent, the affects of Jesus’ raising are murky due to the gospels of Mark and Matthew having very different resurrections—though both versions are decidedly non-violent. In Matthew, Jesus brings life back to the “good” side like Aslan, as “many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised” when Jesus dies (27:52). In describing Jesus’ resurrection, Matthew is clear and dramatic in his telling. An angel descends from heaven—“His appearance was like lightning, and his clothing white as snow,”— and moves the giant stone blocking Jesus’ grave, resulting in an earthquake. He tells Mary Magdalene and the other women watching over his grave that Jesus has been raised and is going to Galilee. Jesus meets them shortly after, reassures them and tells them to tell his disciples he’ll be in Galilee. When they meet, Jesus tells his eleven disciples, “‘All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age,” (Matthew 28:1–20). In this comparison, Lewis replaces the spread of Jesus’ message with the hunting down of the remnants of the White Witches army. Though insistent, Jesus means nothing violent by his words and ends with an assuring promise that he will always be with his followers. Matthew ends his Gospel with a focus on Jesus’ peaceful message radiating outwards to the rest of Israel and beyond, while Lewis ends his book with the extermination of those the main characters deem evil.

The Gospel of Mark has two different endings—one short and one long. The long ending has Jesus appear to various followers in different forms, suggesting his resurrection may not have been a physical one. Jesus’ message to his disciples is much like that of Matthew’s version, as he instructs them to go and spread the word and power of God. The shorter version of Jesus’ resurrection calls into question the very fact of his physical and even spiritual rising. His tomb is empty when Mary Magdalene and others go to check on it, and a young man in white robes is sitting inside. He tells them that Jesus is risen—indeed his body is gone—and that he will meet hid disciples in Galilee. Mary and the others relaying the message to the disciples, “And afterward Jesus himself sent out through them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation” (Mark 16:1–8). Matthew James Ketchum relates the violence of the Roman Empire with Jesus’ empty tomb, calling it a “play of absence and presence, facilitated by Rome’s violent power over life and time,” (229). Ketchum goes on to say, “there is no glorification” in Mark’s conclusion and “questions of Jesus’s humanity and divinity collapse under their own weight” (240-241). The empty tomb seems to symbolize the reality of Rome’s violence. By leaving the tomb empty and not clearly showing a resurrection, Jesus is left in limbo between divine and human. His execution is real—there are no wonderful stories of rejoicing with his followers like Aslan does with Lucy and Susan in LWW. There’s no final hurrah, unlike Aslan’s violent post-resurrection retaliation or Matthew’s glorified and divine Jesus.

When Peter asks Jesus how often he should forgive one who has sinned against him, Jesus replies seventy-seven times.

There is some debate on if Lewis’ Chronicles of Narina is indeed an allegory for the Gospels, though it certainly bears strong resemblance. The missing aspect that may give credit to the doubters is the disconnect between Aslan’s violent solutions and Jesus’ non-violence. Aslan teaches his disciples—children—how to best defend against their enemies with army, sword, and claw. When Peter asks Jesus how often he should forgive one who has sinned against him, Jesus replies seventy-seven times. Essentially, to always forgive your enemies. Jesus preaches forgiveness above all else and leaves his enemies to the violent retribution of God. There is still plenty of violence, or threats of violence, however. Lewis’ Aslan combines the forgiveness of Jesus with the violence of God.

Aslan uses the power he wields, bringing his own judgement against the White Witch and her armies. This contrast can be clearly seen in the aftermaths of Jesus’ and Aslan’s resurrections. Aslan almost immediately rushes to the aid of Peter and the struggling Narnians, sweeping in with his new army and crushing the White Witch and her forces. Jesus, on the other hand, gently appears to his followers, telling them to spread his word. Lewis’ decisions are somewhat understandable given the context of WWII, though one must wonder if the violent agency Lewis gives the children in his works outweighs the potential of Jesus’ non-violent teachings.

Works Cited

Carter, Warren. “Sanctioned Violence in the New Testament.” Interpretation (Richmond), vol. 71, no. 3, 2017, pp. 284-297.

Ketchum, Matthew J. “Haunting Empty Tombs: Specters of the Emperor and Jesus in the Gospel of Mark.” Biblical Interpretation, vol. 26, no. 2, 2018, pp. 219-243.

Neville, David J. “Toward a Teleology of Peace: Contesting Matthew’s Violent Eschatology.” Journal for the Study of the New Testament, vol. 30, no. 2, 2007, pp. 131-161.

Reid, Barbara E. “Which God is with Us?” Interpretation (Richmond), vol. 64, no. 4, 2010, pp. 380-389.

Reid, Barbara E. “Matthew’s Nonviolent Jesus and Violent Parables” Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University, 2006, pp. 27-36.