The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: Myth, Philosophy, and the Bible

Photo by Moira Nichol

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is the third novel to be published in C.S. Lewis’ series of seven Narnia novels. This story is structured very differently from the first two books in the series because its a romance. It follows a long quest, with many exciting adventures, and a path of personal discovery. As an academic, Lewis’ love of Myth, Philosophy, & Christian Apologetics weaves its way its way into the text as he uses Myth, Philosophy and Biblical references to convey his message of spiritual renewal.

As in most monomyths and Romance novels, Lewis’ characters follow a “Heroes Journey”. That is, the call to adventure usually via the supernatural; the crossing of a threshold; facing temptation; physical and mental challenges; a revelation and transformation; atonement; finally, a return to home after being changed by these experiences. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hero%27s_journey

The characters in VDT are called to a quest; the Quest to find the Seven Lords and the Utter East – Aslan’s country. Along their journey they are each changed by their experiences. Eustace by his transformation into a dragon and back, Lucy by her use of the Magicians book, and Edmund in his disagreement with Prince Caspian. We see a hint of this in Lewis’ account of Lucy and Magician’s book.

“But when she looks back the opening words of the spell, there in the middle of the writing, where she felt quite sure there had been no picture before, she found the great face of a lion, The Lion, Aslan himself, staring into hers.” (Lewis:165)

Photo: M.Nichol (Edinburgh Castle)

Join us as this web-page explores several events in the Voyage of the Dawn Treader, where Lewis engages the reader in the elements of myth, philosophy, and the Bible.

When Eustuce Scrubb, and his cousins Edmund and Lucy Pevensie are thrust into Narnia and aboard the Dawn Treader, they have no inkling about the adventures that awaits them or the people they will become.

From the beginning of the story, Lewis uses the theme of the “Platonic Trinity” to tell the story of the spiritual journey of the Eustace, Edmund, and Lucy. These characters are representative of Plato’s description of the three parts of the soul: the logistikon (reason – Eustace, as he prefers science), the thymoeides (spirit – Lucy, as she shows the most compassion), and the epithymetikon (appetite – Edmund, his love of Turkish Delight) . https://books.google.ca/books?id=Y19LAwAAQBAJ&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&dq=platos+tr+trinity&source=bl&ots=ieb8EFNOt-&sig=ACfU3U1FyUrtQ-1jXbp_2YmmyEtlUOlpRw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjCqbDNrqv0AhUF6p4KHVn1DP4Q6AF6BAglEAM#v=onepage&q=platos%20tr%20trinity&f=false

The Lone Islands

The first destination on the journey is the Lone Islands; this is a group of three islands belonging to the Kingdom of Narnia. Deciding to disembark the ship to take a stroll on land Lucy, Edmund, Caspian and Reepicheep are unprepared for the treatment that awaits them there (Lewis 40). They are quickly taken in by slave traders, who have no recognition of Caspian or respect for Narnia (Lewis 43).

The Lone Islands, the Bible, and Moral Ambiguity

Caspian notes that he “never understood” why the Lone islands even “belong to Narnia” and Edmund explains that they’ve been a part of Narnia since before he and his siblings first came through the wardrobe (Lewis 39). Considering how little Caspian knows about his colony, it would seem that the Narnian Kingdom has mostly abandoned the Lone Islands. They soon discover that the Governor of the Islands has become corrupt and greedy and is using the slave trade for financial gain. Caspian, appalled by this, ends the slave trade, removes the position of governor, and appoints Lord Bern as “the Duke of the Lone Islands” (Lewis, 62). Therefore this section of the novel manages to criticize slavery while sympathizing with ideas of colonialism and monarchy. Having virtually no understanding about the issues facing the islands (slavery didn’t develop out of a vacuum), he swoops in to save the day and quickly departs to continue his adventure.

This moral contradiction is echoed by the Bible, which is a very large book (or multiple books), that doesn’t always agree on everything.

This article from Christianity today gives some examples that indicate a pro-slavery stance in Biblical scripture:

https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-33/why-christians-supported-slavery.html

In “The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy: A Case History in the Hermeneutical Tension between Biblical Criticism and Christian Moral Debate” J. Albert Harrill suggests that to find antislavery content in the Bible a “less literal reading” of the text is required (Harrill 153). According to Harrill, going by “Jesus’ so-called Golden Rule, ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’ (Matthew 7:12 and Luke 6:31)”, was and is the way many antislavery christians get around the many conflicting narratives in the New Testament (Harrill 153).

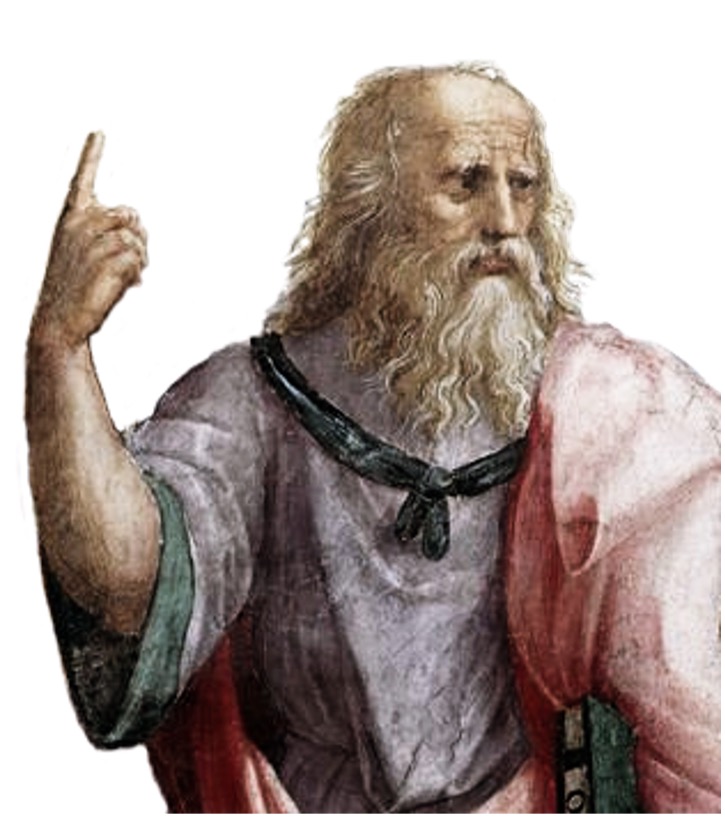

Raphael – Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork

Myth and Philosophy

We see how Lewis weaves myth, philosophy and biblical message into the text. In The Story of the Iliad; The Siege of Troy, (c. 1890) by Edmund Brooks, Brooks tells the story of Homer’s Iliad as an abbreviated version of Homer’s prose narrative written for children. He speaks of a “lonely Island”, somewhat similar to Lewis’ Lone Island. See citations for link to free e-version.

As the children’s adventure continues on Lone Island and King Caspian frees the slaves, we see Lewis address the morality of slavery, “You have lived on broken hearts all your life…if you are beggared, it is better to be a beggar than a slave “(Lewis: 65). In Present Concerns, Lewis makes reference to the philosopher Aristotle’s view on the matter, “Aristotle said that some people were only fit to be slaves. I do not contradict him. But I reject slavery because I see no men fit to be masters”. “C. S. Lewis.” AZQuotes.com. Wind and Fly LTD, 2021. 29 November 2021. https://www.azquotes.com/quote/479496

Lewis’ texts are full of allegory, medieval myth, and religious philosophy. For example, according to Jem Bloomfield, the name (Governor) Gumpas, relates to Plato’s and Alanus’ belief that “gumphus”, translated to mean “small nails”, refers to the nails that tie the soul to the body. Lewis appears to have disagreed, showing his contempt of this by using the word as a name for a useless and ineffectual leader who fails unite and lead his subjects. Bloomfield links this to Lewis’ opinion that Plato’s “gumphus” does not adequately explain how the soul and the body are linked.

Dragon Island: Education and Forgiveness

Photo by K. Mitch Hodge on Unsplash

“Sleeping on a dragon’s hoard with greedy, dragonish thoughts in his heart, he had become a dragon himself”

Lewis 97

The text has set Eustace up as a boy with a massive ego and little imagination, who quickly becomes disliked by his cousins, King Caspian, the crew of the Dawn Treader, and most readers of the novel. Luckily, Eustace’s redemption arc begins with the events on Dragon Island. Here, Eustace goes through a physical transformation that sets in motion his moral discovery.

While avoiding helping the others restock and repair the ship and instead sneaking off to nap, Eustace gets lost (Lewis 81-85). When he comes across a dying dragon and its cave full of treasure he greedily pockets a few items and falls asleep on the pile of gold (Lewis 93).

When Eustace wakes up he slowly comes to realize that he has been transformed into a dragon; “Sleeping on a dragon’s hoard with greedy, dragonish thoughts in his heart, he had become a dragon himself” (Lewis 97). He spends multiple days in this form and it is noted that “his character had been rather improved” during that time (Lewis 107). Despite not being able to talk, Eustace is able to explain his predicament to the crew and he actually begins to make friends (Lewis 106-109). His transformation begins.

Transformation and Education

In Daniel 4, Nebuchadnezzar King of Babylon has a dream, and Daniel interprets it as follows:

“You will be driven away from people and will live with the wild animals; you will eat grass like the ox and be drenched with the dew of heaven. Seven times will pass by for you until you acknowledge that the Most High is sovereign over all kingdoms on earth and gives them to anyone he wishes.”

New International Version, Daniel 4:25

The dream comes true twelve months later as the King ponders his city and his own great power in Daniel 4:30. He has become too boastful and must be punished, or as Jared Beverly views it in his article “Nebuchadnezzar and the animal mind (Daniel 4),” he is educated. Both Eustace and Nebuchadnezzar while in their animal forms learn what they were not capable of while they were human. Beverly explains that “[Nebuchadnezzar’s] animal experience provides him with an understanding of the divine he otherwise would not have known” (Beverly, 153). Similarly, Eustace only meets Aslan because of his transformation and only after he begins to change. Before this experience Eustace tells Edmund that he “hated” even the mention of Aslan’s name (Lewis, 117). Its possible that just like the Pevensie’s had to have faith to see Aslan in Prince Caspian, Eustace had to go through this transformation to receive this honor. Beverly suggests that Nebuchadnezzar had to learn “that only the Most High is truly in charge” and Eustace also learns this when he discovers that he requires Aslan’s help to return to his human form (Beverly, 152).

Eustace and his Internal Battle: Eustace’s transmogrification into a dragon and back to a human echoes many myths. It represents the inner change that happens when Eustace changes from a greedy selfish boy into someone who puts value in the common good. In The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy, edited by Gregory Bassham and Jerry Walls, the writers comment, “Eustace is Lewis’s portrayal of the thoroughly modern secularist.” He is “someone who views the world as a storehouse of physical stuff which science can use for human progress, but who rejects or ignores the ideas of spiritual reality and objective moral values.” https://www.breakpoint.org/sailing-dawn-treader/

We see similar mythological journeys in the stories of Heracles and the Dragon, Thor and the Serpent, and Beowulf and the Dragon.

“Only a philosopher’s mind grows wings, since its memory always keeps it as close as possible to those realities by being close to which the gods are divine.”

― Plato, Phaedrus

https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/879.Plato?page=5

Baptism and Forgiveness

Baptism first appears in the bible along with John the Baptist and it is a practice centered around forgiveness. Luke 3:3 says of John:

“He went into all the country around the Jordan, preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.”

New International Version, Luke 3:3

Aslan appears to the dragon form of Eustace in the night, and he guides him to a pool. There, he helps Eustace undress by peeling off his dragonhide (something Eustace was incapable of doing on his own); and when Eustace is bare, Aslan throws him in the pool where he is returned to his human form (Lewis 115, 116). Even though he has become human once again, he is no longer the same boy he was when he entered Narnia, which is why this ties so nicely into baptism and rebirth. The narrator explains that Eustace was not perfect from then on but “he began to be a different boy … the cure had begun” (Lewis, 119-120). As suggested by Aghiorgoussis “[f]aith precedes, accompanies, and follows Christian baptism … Personal commitment, whether before or following baptism, causes the potential of salvation that is given at baptism to be either active or dormant” (Aghiorgoussis, 28). This baptism by Aslan has not changed Eustace forever, it is his continued faith that will decide his fate.

According to Jeffrey T. Winkle, Lewis uses “thematic and Theological” metaphors in his work.

VDT contains more references to spiritual life than the other texts. Winkle compares Eustace to The Metamorphoses of Apuleius; Apuleius was a c. 160 CE Platonist writer. Winkle compares the transformation of Lucius into an ass, to Eustace’s transformation into a donkey. Both, Winkle argues, are “Platonic sinners”. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190610050.001.0001/acprof-9780190610050-chapter-7

Eustace’s experience of being trapped in a dragon’s body and unable to escape is similar to Plato’s Phaedo where Socrates says: “As long we have a body and our soul is fused with such an evil, we shall never adequately attain what we desire, which we affirm to be the truth”. Lewis points to Eustace not reading the right books (Lewis: 91) and sums it up in The Last Battle when Digory says. “it’s all in Plato,” (Lewis: 212) Of course there are differences; while Plato asserted freedom for the soul came from leaving the material elements of the world behind, Lewis believed freedom came from accepting Jesus as the “word” the “logos”.

The

Magicians

Book & Vanity

On the island of the Dufflepuds, Lucy faces her biggest trial of the journey; vanity. To discover why Lewis parched against vanity, we can look to the Greek tale of Narcissus. Lucy’s meeting with the Dufflepuds led her to the Magician’s book of incantations and spells. She found a spell that would make her more beautiful than most fellow humans. Aslan intervened convincing her she should give up her vain wishes and concentrate on her moral development. Again Lewis brings in mythological allegory.

When Narcissus drank from a perfectly clear pool he saw an exact image of himself. In attempting to kiss this beautiful boy, and he discovering that the image he saw was himself, he nonetheless fell in love.

Through the ages, philosophers have also spoken to the perils of self love; “…when he looks at Beauty in the only way that Beauty can be seen – only then will it become possible for him to give birth not to images of virtue (because he’s in touch with no images), but to true virtue [arete] (because he is in touch with true Beauty). The love of the gods belongs to anyone who has given to true virtue and nourished it, and if any human being could become immortal, it would be he.”

The Sea Serpent and Death Water Island

Photo by Peter Olexa on Unspla

As the Dawn Treader sails across the open ocean they encounter a Sea Serpent. This is when (according to the narrator) “Eustace … did the first brave thing he had ever done” and he attacks the huge creature with a sword (Lewis, 124). Here we see that Eustace hasn’t reverted back to his old self, his faith is intact. They end up defeating the Serpent by outwitting it and sail away relatively unscathed (minus the stern) (Lewis 127). (In the bible serpents are often used to represent clever trickster types, Lewis may be subverting that here).

After sailing several more days they come to another small island. Here, they come across a pool with what appears to be a gold statue resting at the bottom but they quickly realize that it’s not a statue at all, but a body turned to solid gold (Lewis 135). When they discover that the pool has the power to turn anything it touches into the precious metal, Caspian has a realization: “The King who owned this island” he says, “would soon be the richest of all Kings of the world” (Lewis 136).

Deathwater: Temptation and Greed

This is the first of two times that Caspian faces temptation in this novel. Interestingly enough, Aslan directly interferes in both instances. The allure of the gold-producing pool leads Edmund and Caspian to face another test; power. They have a complicated dynamic because both are technically kings of Narnia. Up until this point Edmund has been gracious and allowed Caspian to continue to fill the role of leader during his time there. When the prospect of infinite riches is introduced with the magic pool, greed overcomes their friendship. Instead of the two characters overcoming their moral failures on their own merit, Aslan appears to them and they immediately forget the conflict and forget what the pool could do (Lewis 137). By taking the text in this direction Lewis seems to suggest that there are some issues that only God can resolve.

The greedy stir up conflict, but those who trust in the Lord will prosper.

New International Version, Proverbs 28:25

Dark Island: an Exploration of Faith

Photo by Moira Nichol

6 You have put me in the lowest pit,

in the darkest depths.

7 Your wrath lies heavily on me;

you have overwhelmed me with all your waves.

8 You have taken from me my closest friends

and have made me repulsive to them.

9 I am confined and cannot escape;

my eyes are dim with grief.

(New International Version, Psalm 88:6-9)

Dark island is an exploration of faith in both its darkest aspects and its lightest.

After departing the Island of the Dufflepuds, the Dawn Treader sails for thirteen days when Edmund sights what appears to be land (Lewis, 189). When they get close they realize “that it was not land at all … It was a Darkness (Lewis, 190).” They enter it. The darkness is described almost like a portal to another dimension, it seems to swallow them up and eliminate the blue sky behind them; It’s suddenly cold and time doesn’t feel the same (Lewis 194, 195). They discover a man in the gloom who’s eyes “stared as if in agony of pure fear” and it comes to light that this is the Lord Rhoop, (one of the men Caspian set out to search for) (Lewis 196). He explains that “[t]his is the Island where Dreams come true” and emphasize that, that doesn’t just include good dreams (Lewis,197).

Back on the Island of the Dufflepuds, Coriarkin had revealed that a ship carrying four Lords including Rhoop had set sail from the magicians island about seven years ago (Lewis 188). This would mean that Rhoop has likely been trapped on the dark island since then, minus a few days of sailing. Rhoop reveals that he was tempted to the island by talk of a place where dreams come true but he failed to realize what that truly meant (Lewis, 197). Lewis doesn’t reveal much information about Rhoop other than that he was loyal to Caspian’s father, which would indicate he was a good and faithful man. Did Aslan think he deserved to be punished so cruelly? Or was Rhoop simply not worth his attention? It’s not until Lucy calls to Aslan that they are able to find their path out of the darkness. Perhaps Rhoop’s faith wasn’t strong enough. Either way, imagining his time alone in the darkness brings to mind fruitless prayer uttered in Psalm 88, (which can be found in its entirety here: https: //www.biblegateway.com

Photo: M. Nichol

In greek mythology Erebus (or Erebos) represents the personification of darkness and chaos. He spreads mists and turn dreams into nightmares. In the darkness of the Dark Island, it is the Albatross that is seen by Lucy after which she hears Aslan says, “courage dear Heart” (lewis, 197- 200). Albatross was seen by sailors as an omen of good luck. We again witness the “heroes” journey from dark to light. This part of Lucy’s “Heroes” path is the point where the seeker discovers her allies and finds companions to help her move from the unseen (darkness) to the seen (light).

https://qz.com/1436608/this-classic-formula-can-show-you-how-to-live-more-heroically/

Rhoop’s Faith

“We shall never get out. What a fool I was to have thought they would let me go as easily as that. No, no we shall never get out.”

(Lewis, 200)

Photo by Khamkéo Vilaysing on Unsplash

Psalm 88:5 reads: “I am set apart with the dead, like the slain who lie in the grave, whom you remember no more, who are cut off from your care” (New International Version). The Psalm depicts a poet who is living in complete despair and loneliness and who feels abandoned by God. The poet blames God for leaving them their to suffer but they have faith enough to continue to pray to their Lord. Leonard P. Maré suggests that “[t]he psalm is the desperate cry of someone who seeks to connect with YHWH, but the sound of YHWH’s silence explodes in his ears. The psalmist finds himself in the deepest darkness of abandonment and despair” (Maré, 177).

Rhoop has little hope left by the time the Dawn Treader arrives to save him, but the fact that he has continued to survive in the darkness for seven years shows that he hasn’t given up completely. The Lord’s heart has been sewn with doubt and fear in his exile and it shows in his words. Even when he is picked up by the Dawn Treader he doesn’t trust that they will escape, he despairs; “[w]e shall never get out. What a fool I was to have thought they would let me go as easily as that” (Lewis 200).

Lord Rhoop’s predicament and that of the poet in Psalm 88 are similar in that they both directly confront God’s apparent cruelty. It struggles with the question: “if there is a God, why does he let good people suffer”?

Maré argues that the Psalm is a realistic representation of faith, “in Ps 88 faith faces life as it is” (Maré 186). Suffering is real, and faith must find a way to survive in spite of it.

Lucy’s Faith

“Aslan, Aslan, if ever you loved us at all, send us help now”

(Lewis, 200)

Photo Credit: Byron Chin on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/48282656@N00/35724152005

When the crew realize what they have sailed into they begin to panic and the power of the island comes over them (Lewis 198). Only Reepicheep who is renowned for his bravery manages to “remain unmoved” (Lewis 198). As they paddle fearfully through the darkness in an attempt to escape, Caspian realizes that its taking longer than it should and the crew falls deeper into the pit of fear and become convinced that they will “never get out” (Lewis 199). This seems to suggest that their fear is trapping them and leading them deeper into the darkness. This is when Lucy, who has remained impressively calm, calls to Aslan: “Aslan, Aslan, if ever you loved us at all, send us help now” (Lewis 200). Immediately, she gets a response; an albatross appears and guides them back into the light (Lewis 200, 201).

Lucy’s faith is the focal point of her character in many of the novels in the Narniaverse. In the Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe it is she who discovers the doorway to Narnia and persists in showing the world to her siblings despite their dismissal of her. In Prince Caspian, she sees Aslan when the others don’t, and though she faces her siblings’ ridicule once again, she keeps her faith and is found to be right. Lucy is kind and sees the good in everyone. She is never afraid of Aslan like others often are. She’s more familiar with him, because as Edmund explains to Eustace in the Voyage of the Dawn Treader she “sees him most often” (118). He may be unsafe but she trusts that he is good. Lucy’s bond with Aslan is the guiding light to deliver them from fear.

“I sought the Lord, and he answered me; he delivered me from all my fears.”

New International Version, Psalm 34:4

Temptation in the East: the Last Sea

Photo by Matt Paul Catalano on Unsplash

“Then the man brought me to the gate facing east, and I saw the glory of the God of Israel coming from the east. His voice was like the roar of rushing waters, and the land was radiant with his glory”

New International Version, Ezekiel 43:1-2

Shortly after leaving Ramandu’s island, the Dawn Treader comes to the Last Sea. The world has been altered; the sun is much larger and the ocean is extremely clear (Lewis 237, 238). Lucy gazes overboard and spots an underwater city inhabited with Sea People, but when Drinian sees what she is looking at he warns her not to tell anyone else:

“It’ll never do for the sailors to see all that … we’ll have men falling in love with a sea-woman, or falling in love with the under-sea country itself, and jumping overboard” (Lewis 245).

Apart from this being a reference to Siren’s in mythology, this also ties into the biblical theme of temptation. This theme continues into the Silver Sea, where Caspian is tempted to forgo his duties as King of Narnia and seek adventure.

The meaning of “East”

In the Bible:

There has been some discussion on blogposts about what exactly the Eastern direction symbolizes in the Bible, because it is mentioned fairly often. Both sources below noticed a pattern of holiness coming from the east but negative implications for the humans who travel there.

Both God and the Messiah appear to come from the east according to scripture.

“For as lightning that comes from the east is visible even in the west, so will be the coming of the Son of Man”

New International Version, Matthew 24:27

Conversely for humans the east represents the original sin committed by Adam in the Garden of Eden, as well as a place of exile for Cain when he kills Abel:

“So Cain went out from the Lord’s presence and lived in the land of Nod, east of Eden” – Genesis 4:16

In Narnia:

In the Voyage of the Dawn Treader Aslan’s country is said to lie in the east, and the ship sets off with reaching that land as one of their goals; Reepicheep says: “[i]t is always from the east, across the sea, that the great Lion comes to us,” just as with God and the Messiah in the Bible (Lewis, 21). Going east in Narnia isn’t a bad thing but it does come with trials and danger. As we’ve seen, each of the characters must overcome their moral failures to receive the honor of reaching Aslan’s country. The east is reserved for only those who prove themselves worthy.

“We have nothing if not belief.” Reepicheep (Lewis:267)

Photo: M.Nichol

“I am the alpha and the omega” is further clarified with the additional phrase, “the beginning and the end” Revelation 21:6, 22:13.

Bible Gateway

Temptation and Salvation

Even as far east as the Silver Sea, the characters continue to be tried. It is here where Caspian faces his greatest test. He attempts to ditch the crew and go east to Aslan’s country with Reepicheep to pursue adventure over duty.

In “Basic Plots in the Bible: A Literary Approach to Genre,” author Harry Hagan discusses the various themes and plots in the Bible and other literature. Hagan suggests that “much of the Bible narrates a journey, and ultimately a journey to God” (Hagan, 202). God is the ultimate destination of the journey in the Voyage of the Dawn Treader as well, even if that wasn’t the intention of the characters initially. He explains that in a story of “voyage and return” the characters don’t necessarily set out with a specific goal but instead with the “allure of possibility” and when they return they have been transformed (Hagan, 203). According to Hagan, “trials and temptations” are “subplots for journey” (Hagan, 203).

Characters in the bible are often tested to prove their worth. In Genesis 3, Adam and Eve are tempted to eat the forbidden fruit by the serpent who tells them that they will then “be like God, knowing good and evil” (New International Version Genesis 3:4). When God discovers this, he punishes them cruelly for being so easily tempted into disobeying Him (New International Version Genesis 3:16-24).

When Caspian is tempted to abandon his duty Aslan visits him through a lion statue, and although he isn’t cruel “only a bit stern” he tells Caspian that he must go home, while others go on (Lewis 262). Caspian has for the second time in this novel failed to resist temptation. Despite this, Aslan is forgiving and kind, at least in comparison to God in Genesis 3. Throughout the series Aslan is seen as terrifying and powerful, but although he is unsafe he’s undoubtedly good. If Lewis did have a religious agenda while writing these novels, I would argue that it was to show that God is also good.

The end of the story is the conclusion of the journey; the characters have reached their destination, their quest is fulfilled. Reepicheep finds the path to Aslan’s country, Prince Caspian finds the courage to follow his kingship duties, and the children return to England, forever changed by their Narnia experiences. Just as the sun rises in the east (the alpha) and sets in the west (omega), so the beginning of their new life is the end of the old one.

Conclusion

Myth has always been an important part of human learning. The telling of mythical stories is part of socialization and human ancestral links. Just as the Bible, tells the historical journey of a people, so do mythical stories impart symbolic messages of the past and urge us to live a “good life”. Mythology helps us understand our past, and learn from our ancestor’s mistakes. Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living”. Lewis’ Chronicles urges us to examine our life; he calls to us today to examine not just greed, vanity and faith, but as unintended as it may have been, to learn from his mistakes. As we read his work today, we learn how corrosive racism, consumerism, colonialism, sexism, and exclusivism is. To read and interpret the Biblical references along with his mythical and philosophical ones, helps us examine our life and our responsibility to all of nature, human or otherwise.

Works Cited

Aghiorgoussis, Maximos. “The Meaning of Christian Baptism for the Baptized and for the Church.” Greek Orthodox Theological Review, vol.55, issue 1-4, 2010, pp.19-48.

Beverly, Jared. “Nebuchadnezzar and the Animal Mind (Daniel 4).” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, vol. 45, no. 2, Dec. 2020, pp. 145–157, doi:10.1177/0309089219882447.

Hagan, Harry. “Basic Plots in the Bible: A Literary Approach to Genre.” Biblical Theology Bulletin, vol. 49, no. 4, Nov. 2019, pp. 198–213, doi:10.1177/0146107919877640.

Harrill, J. Albert. “The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy: A Case History in the Hermeneutical Tension between Biblical Criticism and Christian Moral Debate.” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, vol. 10, no. 2, [University of California Press, Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture], 2000, pp. 149–86, https://doi.org/10.2307/1123945.

Lewis, Clive S. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Harper Trophy, 1980.

Maré, Leonard P. “Facing the Deepest Darkness of Despair and Abandonment: Psalm 88 and the Life of Faith.” Old Testament Essays, vol. 27, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 177-188, https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC152826.

Matt. “Look To The East: What do directions mean in the Bible?” The Left Hand of Ehud: Matt’s Bible Blog, WordPress, July 13, 2012, https://mattsbibleblog.wordpress.com/2012/07/13/look-to-the-east-what-directions-mean-in-the-bible/. Accessed Dec. 2021.

New International Version. Biblica, 2011. Bible Gateway, https://www.biblegateway.com/

Oka, Rich. “2-21: The significance of the direction “East” in the Scriptures” Welcome to the Messianic Revolution, https://messianic-revolution.com/2-21-significance-direction-east-scriptures/. Accessed Dec. 2021.

Plato. The Dialogues. https://webs.ucm.es/info/diciex/gente/agf/plato/The_Dialogues_of_Plato_v0.1.pdf

“Why Did so Many Christians Support Slavery?” Christianity Today, Christian History, 1 Jan. 1992, https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-33/why-christians-supported-slavery.html.

Winkle, Jeffrey T. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/vie