Edited By Aaron Burgess

“I have seen the extreme vanity of this world:

One hour I have been in health, and wealthy, wanting nothing. But the next hour in sickness and wounds, and death, having nothing but sorrow and affliction.”

– Mary Rowlandson

I can remember the time when I used to sleep quietly without workings in my thoughts, whole nights together, but now it is other ways with me.1 When all are fast about me, and no eye open, but His who ever waketh, my thoughts are upon things past, upon the awful dispensation of the Lord towards us, upon His wonderful power and might, in carrying of us through so many difficulties, in returning us in safety, and suffering none to hurt us.2 I remember in the night season, how the other day I was in the midst of thousands of enemies, and nothing but death before me. It is then hard work to persuade myself, that ever I should be satisfied with bread again.3 But now we are fed with the finest of the wheat, and, as I may say, with honey out of the rock.4 Instead of the husk, we have the fatted calf.5 The thoughts of these things in the particulars of them, and of the love and goodness of God towards us, make it true of me, what David said of himself, “I watered my Couch with my tears” (Psalm 6.6). Oh! the wonderful power of God that mine eyes have seen, affording matter enough for my thoughts to run in, that when others are sleeping mine eyes are weeping.6

I have seen the extreme vanity of this world: One hour I have been in health, and wealthy, wanting nothing. But the next hour in sickness and wounds, and death, having nothing but sorrow and affliction.7

Before I knew what affliction meant, I was ready sometimes to wish for it. When I lived in prosperity, having the comforts of the world about me, my relations by me,8 my heart cheerful, and taking little care for anything, and yet seeing many, whom I preferred before myself, under many trials and afflictions, in sickness, weakness, poverty, losses, crosses, and cares of the world,9 I should be sometimes jealous least I should have my portion in this life, and that Scripture would come to my mind, “For whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth, and scourgeth every Son whom he receiveth” (Hebrews 12.6). But now I see the Lord had His time to scourge and chasten me.10 The portion of some is to have their afflictions by drops, now one drop and then another; but the dregs of the cup, the wine of astonishment, like a sweeping rain that leaveth no food, did the Lord prepare to be my portion.11 Affliction I wanted, and affliction I had, full measure (I thought), pressed down and running over.

Yet I see, when God calls a person to anything, and through never so many difficulties, yet He is fully able to carry them through and make them see, and say they have been gainers thereby. And I hope I can say in some measure, as David did, “It is good for me that I have been afflicted.”13 The Lord hath showed me the vanity of these outward things. That they are the vanity of vanities, and vexation of spirit, that they are but a shadow, a blast, a bubble, and things of no continuance. That we must rely on God Himself, and our whole dependance must be upon Him.14 If trouble from smaller matters begin to arise in me, I have something at hand to check myself with, and say, why am I troubled? It was but the other day that if I had had the world, I would have given it for my freedom, or to have been a servant to a Christian. I have learned to look beyond present and smaller troubles, and to be quieted under them.15 As Moses said, “Stand still and see the salvation of the Lord” (Exodus 14.13).

Finis.

Thanks to Project Gutenberg for providing the digitized version of this text free of charge. Without their generosity, this project would not be possible.

Works Cited:

Arsić, Branka. “Mary Rowlandson and the Phenomenology of Patient Suffering.” Common Knowledge, vol. 16, no. 2, 2010, pp. 247-275.

Traister, Bryce. “Mary Rowlandson and the Invention of the Secular.” Early American Literature, vol. 42, no. 2, 2007, pp. 323-354.

Bennet, Bridget. “The Crisis of Restoration: Mary Rowlandson’s Lost Home.” Early American Literature, vol. 49, no. 2, 2014, pp. 327-356.

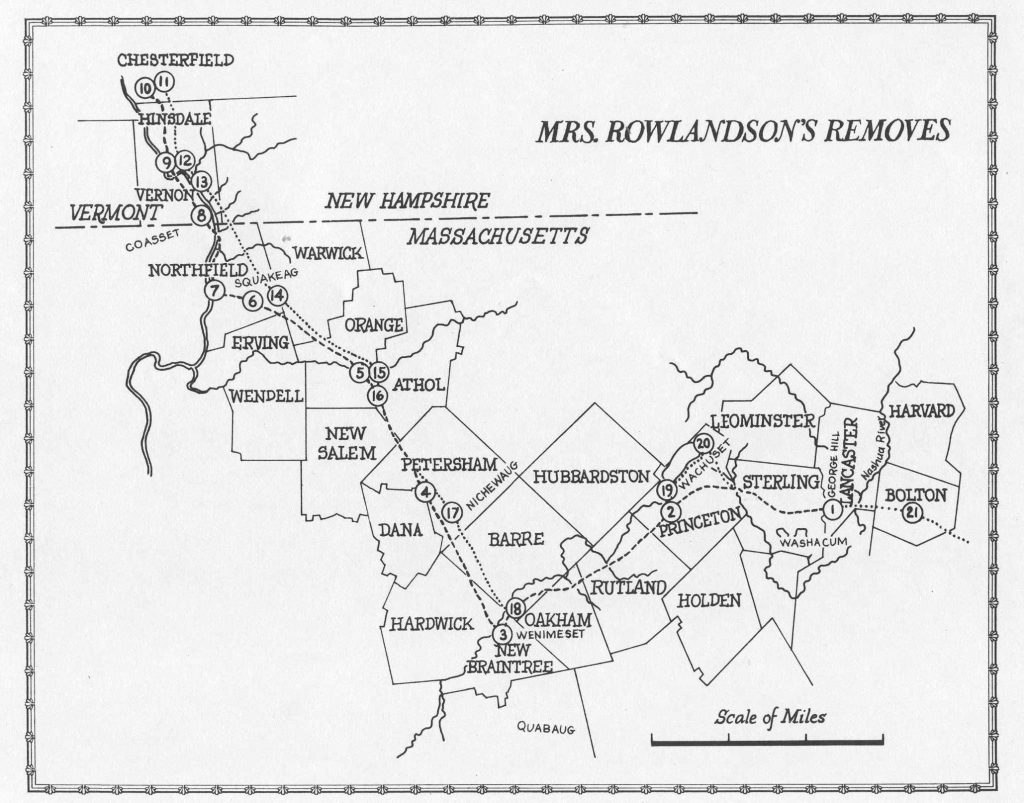

Cloyd, Aaron. “A Posture of Removal: Mary Rowlandson’s Location, Position, and Displacement.” DisClosure (Lexington, Ky.), vol. 23, 2014, pp. 78.

Rowlandson, Mary White. The Soveraignty & Goodness of God. E-Book, Internet Archive, 1682. https://archive.org/details/soveraigntygoodn00rowl/page/n11/mode/2up. Accessed Nov 12th 2020.

This opening passage has been examined in depth by scholar Bryce Traister, found in his article “Mary Rowlandson and the Invention of the Secular.” – “As a mental portrait,… the passage sketches an itinerant mind roving from the narrative present (‘I can remember’), to the remote past of unconscious life (‘used to sleep quietly’), back to a present radically different from that past (‘but now it is other’), and then back to a past identified as a haven from the turmoil of her sleepless present (‘my thoughts are on things past’) (323). ↩

“Mary Rowlandson’s ‘restoration’ is imperfect; her sleeplessness registers the incompleteness of her redemption, testifying simultaneously to her desire to thank God for her rescue from captivity, and to her ongoing spiritual search for the assurance that Gods wondrous power has indeed provided for her restoration to English community, if not for her spiritual redemption (Traister 324). ↩

“There is virtually no Remove in The Sovereignty and Goodness of God that is not marked by reference to food” (Arsić 249). – This point is noteworthy, as there is a punctuated relationship between physical food, as sustenance, and metaphysical nourishment through God; and can be examined more extensively in Branka Arsić’s article “Mary Rowlandson and the Phenomenology of Patient Suffering.” ↩

Psalm 81:16 ↩

Luke 15:22 – this is a pertinent allusion, as it is made in reference to the prodigal son and imposes a comparison between this figure, who is explicitly male, and the transgressive, social status of Rowlandson herself. ↩

“Puritan pragmatics thus substituted an ideal – a disembodied type – for the reality of individual loss. This idealistic switch was essential in disciplining the psychic dynamic, reshaping its remembering from mourning into exemplarism” (Arsić 248). ↩

Though inexplicit, this passage is thematically reminiscent of the parable of the Book of Job. ↩

Bridget Bennet’s article, “The Crisis of Restoration: Mary Rowlandson’s Lost Home”, offers a nuanced analysis of Rowlandson’s restoration, especially as it pertains to the removal of home, or the loss of home within community. – “Home is what is lost to Rowlandson at the start of the narrative and is what she aims textually, affectively, and materially to rebuild” (Bennet 328). ↩

“The restoration of Mary Rowlandson is also a reinstatement of one set of claims of home and a legitimization of the processes —including the violence— of colonization, settlement, and nation building. Though these are evidently (and importantly) political, economic, and religious, they also have a strong affiliative and affective element” (Bennet 328). ↩

“In the Protestant-Calvinist framework, affliction becomes meaningful within a rendering of saintly perseverance…” (Traister 325). ↩

This passage is highly reminiscent of Transubstantiation – especially when considered alongside passages pertaining to bread – and is made especially curious due to the correlation between its ritual practice and Catholicism, to which Rowlandson as a Calvinist-Puritan would have been strongly opposed. ↩

Aaron Cloyd offers a comprehensive analysis of the geography, and topographical relevance of Rowlandson’s removes in his article “A Posture of Removal: Mary Rowlandson’s Location, Position, and Displacement.” ↩

Psalm 119:71 ↩

Again, there seems to be a correlation between reference made to David, followed swiftly by thematic renderings of Job. ↩

Branka Arsić notes the quietest significance of this final passage, and furthers an examination in her article “Mary Rowlandson and the Phenomenology of Patient Suffering.” – “Thus Rowlandson’s testimony to the quietist strategy that preserved and yet transformed her concludes with an invocation of triumphant stillness: ‘as Moses said, Exodus 14.13. Stand still and see the salvation of the Lord’” (Arsić 275). ↩