Edited by Dane Larsen

But instead of going either to Albany or homeward, we must go five miles up the river, and then go over it.1 Here we abode a while. Here lived a sorry Indian, who spoke to me to make him a shirt. When I had done it, he would pay me nothing. But he living by the riverside, where I often went to fetch water, I would often be putting of him in mind, and calling for my pay: At last he told me if I would make another shirt, for a papoose not yet born,2 he would give me a knife, which he did when I had done it. I carried the knife in, and my master asked me to give it him, and I was not a little glad that I had anything that they would accept of, and be pleased with. When we were at this place, my master’s maid came home; she had been gone three weeks into the Narragansett country to fetch corn,3 where they had stored up some in the ground. She brought home about a peck and half of corn.4

This was about the time that their great captain, Naananto,5 was killed in the Narragansett country. My son being now about a mile from me, I asked liberty to go and see him; they bade me go, and away I went; but quickly lost myself, traveling over hills and through swamps, and could not find the way to him. And I cannot but admire at the wonderful power and goodness of God to me, in that, though I was gone from home, and met with all sorts of Indians, and those I had no knowledge of, and there being no Christian soul near me; yet not one of them offered the least imaginable miscarriage to me.6 I turned homeward again, and met with my master. He showed me the way to my son. When I came to him I found him not well: and withall he had a boil on his side, which much troubled him. We bemoaned one another a while, as the Lord helped us, and then I returned again. When I was returned, I found myself as unsatisfied as I was before. I went up and down mourning and lamenting; and my spirit was ready to sink with the thoughts of my poor children. My son was ill, and I could not but think of his mournful looks, and no Christian friend was near him, to do any office of love for him,7 either for soul or body. And my poor girl, I knew not where she was, nor whether she was sick, or well, or alive, or dead. I repaired under these thoughts to my Bible (my great comfort in that time) and that Scripture came to my hand, “Cast thy burden upon the Lord, and He shall sustain thee” (Psalm 55.22).8

Thanks to Project Gutenberg for providing the digitized version of this text free of charge. Without their generosity, this project would not be possible.

Reference to Connecticut River. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Connecticut_River. ↩

A young North American Indigenous child. (“papoose, n.”. OED Online. September 2020. Oxford University Press.) ↩

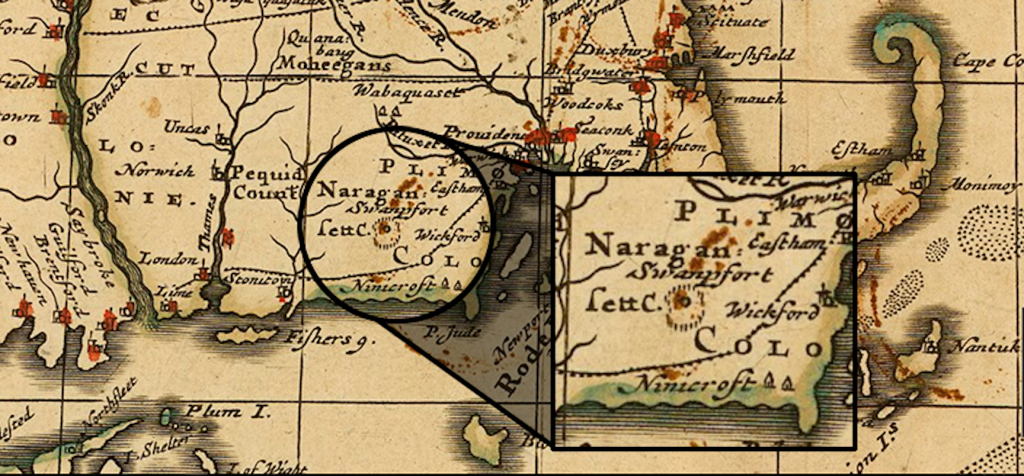

Narraganset Country: A large region controlled by the Narraganset people, during the period, in what is now south-eastern Rhode Island. ↩

A unit of capacity for dry goods equal to a quarter of a bushel, now equivalent (in Britain) to two imperial gallons (approx. 9.09 litres). (“peck, n.1”. OED Online. September 2020. Oxford University Press.) ↩

Harvey Markowitz., and Carole A. Barrett, American Indian Biographies (Pasadena, California: Salem Press, 2005), 81. Referred to in the text as Captain Naananto, more properly referred to as Canonchet or Nanuntenoo. He led the Narragansett peoples and was executed in April, 1676 by British forces. ↩

Billy J. Stratton, “‘Like a Company of Sheep Torn by Wolves’: Transatlantic Influence on the Developement of the Indian Captivity Narrative,” in Buried in Shades of Night: Contested Voices, Indian Captivity, and the Legacy of King Phillips War (University of Arizona Press, 2013), 34. Just as Rowlandson’s narrative, through its publication, shaped perceptions of indigenous peoples, so too does she make use of these same perceptions to depict the indigenous as savage as “fear for her virtue,” despite no serious harm coming to her during her captivity. In Rowlandson’s mind it can only be through the “power of God” that she remained unharmed. ↩

Paul Althaus, “The Ethics of Martin Luther,” ECLA, Journal of Lutheran Ethics, December 1, 2001, https://www.elca.org/JLE/Articles/1039. Possible reference to Martin Luther’s ideas of an “office of love,” which is serving and protecting others, or a more codified set of rituals. If either is the case it is unclear why Rowlandson herself cannot perform the “office of love” as she does not call for a minister or priest but a “Christian friend” to aid her son. ↩

Rowlandson cites Psalms 55:22, but the next verse is of interest as well given her situation. Psalms 55:23, “But thou, O God, shalt bring them down into the pit of destruction: bloody and deceitful men shall not live out half their days, but I will trust in thee.” Taken together, she is not only looking for comfort for herself, but also destruction and despair for her captors. Psalms 55:19, “God shall hear, and afflict them, even he that abideth of old.” ↩