The Winnipeg General Strike had a lasting effect on women within the province and the rest of the nation. Although in the end, the strike did not achieve its main goal of collective bargaining and unionization, it was still a success in many areas. It was another important step forward for the union movement and collective bargaining. It was also a time of increased equality for women, as they were right beside males throughout the strike. Women left their jobs, organized into social and political clubs, marched in the streets, served meals in a food kitchen, and took part in the chaos at times. According to Canadian social activist Beatrice Brigden, the strike helped women achieve “the right to organize, it got them the right to speak up for themselves, and they began to have some legislation such as control of wages and led on to a minimum wage and led on to women getting into organizations too and the right to be recognized and the right to organize, that was the big thing” (Horodyski). The Winnipeg General Strike played a key role in advancing women socially and politically in Canada in the 20th century.

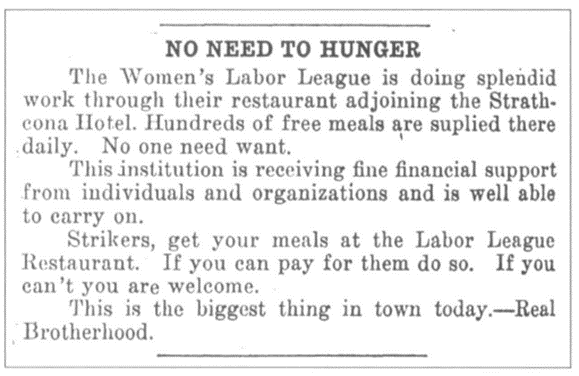

This newspaper clipping is from Western Labour News in May of 1919. The clipping came when the Women’s Labor League was handing out free meals to help striking citizens in need (Naylor, 77).

Food Kitchen

Arguably the most significant contribution by women to strikers’ efforts in the summer of 1919 was the opening of a food kitchen. About one week into the strike, the Women’s Labor League, led by Helen Armstrong, created a food kitchen in the Strathcona Restaurant in downtown Winnipeg (Kelly). Armstrong named it the Labour Café and it was extremely successful. The kitchen served 1200 to 1500 meals daily, all of which were free. The main priority of the Labour Café was to feed women strikers, however, they were willing to give meals to anyone in need. When serving men food, they asked for a donation of some sort. The Labour Café was crucial to the perseverance of women strikers because finding or affording food was difficult for some. A small portion of the Winnipeg population were widows due to the Great War and were completely reliant on only one income. Others had no money saved up, or had large families and were pressured by the number of mouths to feed. This drove some women to take part in scab work, which meant they had to cross the picket line. It is because the strike ended up only having a duration of six weeks that some women’s ability to purchase food and the availability of food did not become a serious matter.

Helen Armstrong fought for women to receive higher wages and more civic rights in the Winnipeg General Strike (Kelly).

Helen Armstrong

Helen Armstrong was a prominent figure for females during the Winnipeg General Strike. She was a mother of four and a part of the working class who became a voice for women in 1917 when she started working with the Women’s Labor League. After two years of service, she was promoted to the president of the organization. She was also presented with the opportunity to join the Central Strike Committee and was one of the two women on the committee of fifty individuals. Armstrong was an advocate for all women during the strike, and she was notably against wage inequality. Academic Paula Kelly explains Armstrong’s significance in a time of turmoil, stating “Whether walking the picket line, making her case in the provincial legislature, or facing the police court magistrate, Helen Armstrong was an outspoken and vigorous advocate for all labouring women: laundresses, retail workers, stenographers, telephone operators, hotel waitresses; the list went on and on. In one letter to the deputy minister of labour, she went to bat for the candy-industry girls, citing case after case of poor wages, constant layoffs, and petty persecutions that made ‘the lives of many of our working girls … so unbearable that in the end the street claims them as easy prey.” Armstrong was also a major driving force in the organization of women. She believed that women organizing would result in social, political, and economic improvements. She shared in a letter to the editor of a Canadian newspaper that “Girls have got to learn to fight as men have had to do for the right to live, and we women of the Labor League are spending all our spare time in trying to get girls to organize as the master class have done to protect their own interests” (Kelly). The leadership from Armstrong is credited as a major factor in women’s participation in unions and labour activism (McMaster, 125). Armstrong’s overall intensity and devotion to activism eventually led to her being thrown in jail, as she was intent on making sure scabbing employees understand their work was not appreciated by the strikers.

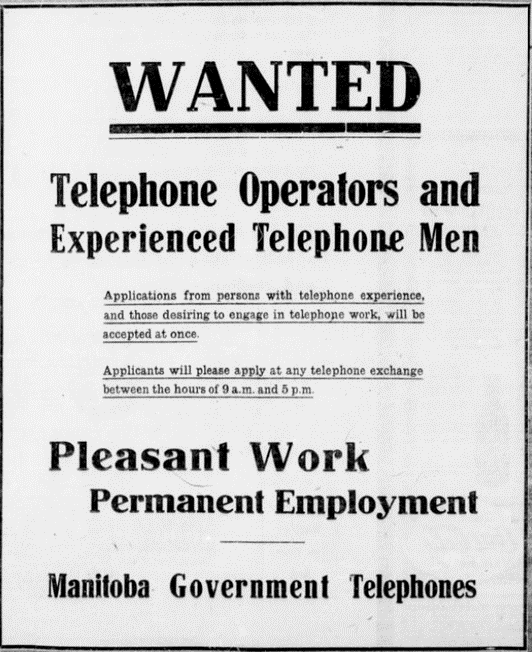

One June 2, 1919, The Winnipeg Evening Tribune published this wanted advertisement for telephone operators. Telephone operators had been off for a few weeks, and the Manitoba government was in desperate need of workers (The Winnipeg Evening Tribune).

Telephone Operators

Telephone Operators played an important role in the Winnipeg General Strike. Since the 1880s in Canada, the job of an operator had become primarily women’s work. Groups of women would sit at a switchboard with headphones on, and connect different callers. This work was seen as prestigious by many because the operator was key to connecting individuals through communication technology and they were also a source of general information for callers (McLean, 376). The 1919 Strike was not the first time that telephone operators had rebelled against their employers. Two years earlier in 1917, Winnipeg women had been a part of union disputes when they fought for a salary increase of fifteen to forty percent (Horodyski). On May 1st, 1917, operators conducted a three-hour strike to gain their employer’s attention. When disputes began in the summer of 1919, many operators were comfortable and familiar with having conflict with their employer.

Telephone operators were crucial in starting the city-wide strike. On May 15th, 1919, five hundred telephone operators walked out and pulled the switches which left a majority of Winnipeg with no phone service. There were no workers that came in to replace them. At this point, the only strikers were the metal and building trades workers and around five hundred female bakery and confectionary workers who were on strike because their employer was refusing to negotiate with the union (McMaster, 135). By midnight on May 15, over 20,000 people had joined the strike (McMaster, 135). Employees from shops, factories, offices, railyards, restaurants, theatres, and fire halls had left their postings (Horodyski). All telephone lines in the province were shut down by May 26th. Some women did come back to work as operators mid-way through the strike, as they were offered plenty of money and some people’s financial situations had become dire after several weeks with no pay. Volunteers joined in as well, although they were overwhelmed with the work (Horodyski).

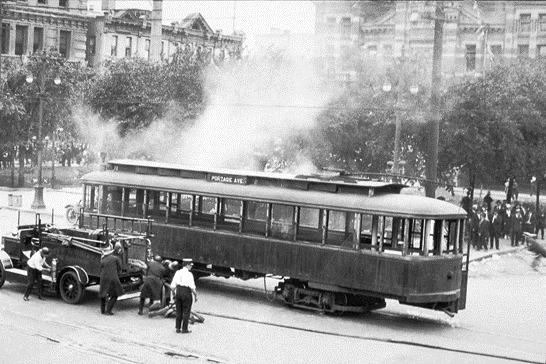

The infamous streetcar that was lit on fire by a female on Bloody Saturday. This is one of the many aggressive actions protestors performed to express their dissatisfaction with their employers and the Citizens Committee. The events of Bloody Saturday escalated until two protestors were killed by the RCMP (Bernhardt).

Women Striking

Women in the strike were alongside men fighting for better working conditions, collective bargaining, and the ability of industrial unionism. Their primary concern, however, was earning more money. At the time, women were receiving less than a living wage (Horodyski). Women became involved in all areas of the strike, as they acted as protestors, rioters, and scabs. There were several headlines and reports of women being arrested for being members of unlawful assembly and intimidation. Women were active, especially in the working-class areas of Winnipeg. In these parts of town, “women pulled scab firemen from the firehall and wrecked department-store delivery trucks. Others intimidated strike-breakers who lived in their neighborhoods” (Heron, 185). A female protestor is also credited with lighting the streetcar on fire on Bloody Saturday (Horodyski). Some women’s focus during the period of the strike was less on destruction and revolt and more on surviving. There was a decent population of women workers who were in desperate need of a paycheque. Therefore, females started selling and distributing newspapers to earn some cash. Papers like the Winnipeg Evening Tribune and the Western Labor News offered women these jobs. The papers supported striking women by temporarily replacing the young men they had doing these jobs with struggling females.

Outside City Hall in Winnipeg on June 21, 1919, a large crowd gathered. Crowds like this became common during the strike’s six-week duration (Lowry).