Part 1: An Introduction to the Common Loon

It’s a peaceful July evening in northern Canada’s lake country. The sun is setting, and the water has turned into a reflective surface for the vibrant sky. The temperature drops a degree and everything seems to calm as you settle into your Adirondack chair on the dock. Then, out of nowhere echoes the hauntingly beautiful call of one of Canada’s most notorious water birds.

(Audio from Macaulay Library)

Perhaps you have no idea of what I speak. In this case, I urge you to empty your pockets and take a peek at your Canadian one-dollar coin.

Description and Identification

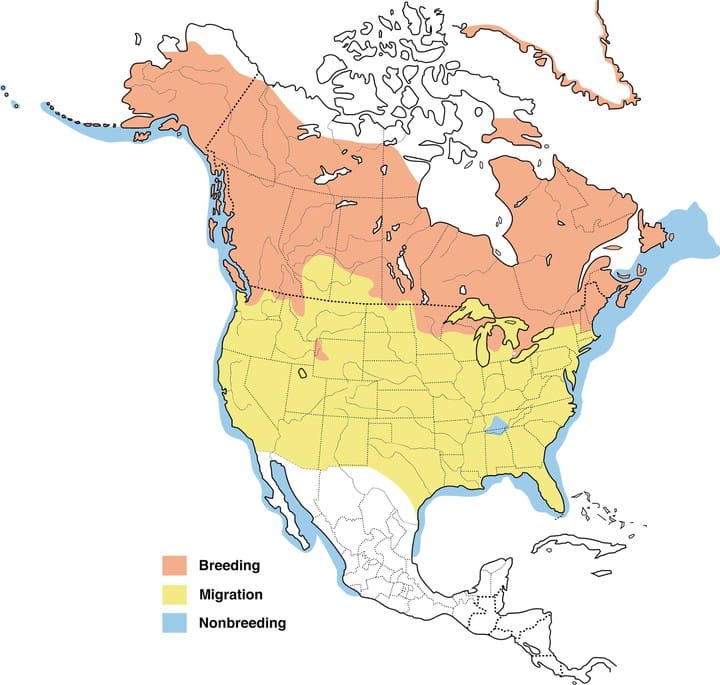

The common loon (Gavia Immer) is one of five species across North America and Northern Eurasia that make up the genus Gavia. Gavia are known for being clumsy, primitive water birds. In summer months, the common loon can be spotted in Northern lakes, and is distinguishable by its breeding plumage; beautiful black and white feathers and a ruby red eye. In winter, the common loon migrates to coastal ocean waters, and resembles its juvenile plumage with relatively drab greys and browns. (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2010).

The common loon is much larger than most people think. With a wingspan of over 4 feet, a common loon with outstretched wings is about as long as a 7-year-old child is tall (Livestrong, 2019). Not only are they large, but Gavia genus birds are also extremely heavy compared to land birds of the same size, weighing in at over 13 lbs. This stark difference in weight can be attributed to the bones of diving birds. While most birds have adapted hollow bones to assist in flight, loons have solid bones. This allows them to dive deep and swim quickly but comes at the cost of rapid take-off (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2010).

(photos by John Picken– L, and Peter Vercruijsse– R)

Behaviour

Loons need to be fantastic swimmers because the majority of their food dwells in the water. Loons typically feed on fish but will settle for frogs, crayfish, mussels, leeches, and aquatic insects. They rely on their eyesight to catch their prey. When ready to dive, loons can exhale and flatten their feathers to remove air (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2010). Powerful hind legs propel their heavy bodies toward prey, and solid bones provide mass and eliminate buoyancy. These strong hind legs are set further back than most birds to provide the loon with exceptional diving skills (up to 90m!) but are paid for by clumsy locomotion on land. Instead of staying upright like ducks, loons use a push and slide technique on land- it’s no surprise they spend so much time in the water (University of Iowa Press, 2009; Clifton & Biewener, 2019).

Unfortunately for loons, what makes them so good at swimming sometimes becomes their demise. Like airplanes, they require a long runway of water to paddle themselves into flight. When flying at night and in low visibility weather, loons have been recorded to land on small lakes and ponds (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2010). With not enough room to take-off, they become stranded and eventually die where they landed. Similarly, loons can mistake parking lots and roadways for clear water in the dark. This results in crash landings, and even if the loon survives, it can’t take off to feed, find a mate, and have hatchlings (Glacier National Park, 2005).

Nesting

Despite their poor adaptations to land, loons haven’t yet evolved an effective way to nest in the water. Instead, they build nests within 50cm of the water’s edge. Both females and males contribute to nest construction on islands or backwaters, using cattails, grasses, and twigs (Strong, Bissonette & Fair, 1987). Loons occupy their breeding grounds immediately after the ice melts on the lakes. Within a month, adorable downy black-brown hatchlings with awkwardly positioned legs take their first wobbles. However, the awkwardness pays off quickly. Within 2-3 days, newly hatched loons can dive and swim underwater (Audubon, 2019). The young tend to hitch a ride on parents’ backs to conserve warmth and energy until they can fly at 10-11 weeks (Algonquin Park, 2004).

Quickly after hatching, juvenile common loons learn the definition of tough love. Parents flock south on their own and leave the juveniles behind. Luckily, the young birds find solace in each other and flock to coastal ocean waters together. The juveniles stay in coastal habitats for 2 years, then return to northern lakes to breed and have young of their own (Pittaway & King, 2019).

Not only will breeding common loons usually return to the same nest the following year, but they will often return with the same mate. Despite this blog title, loons are genetically monogamous birds. Much like (some) humans, they find a mate and stick with them. Rarely is there extra-pair copulation during this time (The Loon Project, 2018). When separated, both the male and the female make extensive efforts to locate their counterparts (Piper et al., 1997). In fact, part of this localization attempt comes in the form of the iconic eerie call heard at the beginning of this blog. One loon calls out and waits for the other to reply to guide its search efforts. The next time you hear a loon call, just think- you’re listening to a bird version of Marco Polo (The Cornell Lab, 2018)! The loons have a completely different sound to signal alarm, heard below. That’s pretty neat!

(Audio from Macaulay Library)

Conservation Status

Currently, loons are considered “climate endangered”. While their population has decreased slightly due to human disturbance on once untouched lakes, there is a larger threat at hand. Within 60 years, Audubon suspects that Common loons will lose 56% of their summer range and 75% of their winter range due to global warming (Audubon, 2019).

Part 2: Flooding and Fledglings- The Impact of Climate Change on Common Loon Nesting Success

As mentioned above, loons are clumsy land trotters. They can’t effectively travel long distances so they form their nests very close to the shoreline to avoid the awkward shuffle. Male loons choose suitable real estate, and the pair get to work scavenging vegetation for a nest. However, the fact that nests are only 10cm above the water surface causes a critical issue when water levels are unpredictable (Windels et al., 2013).

In 2019, the Lake of Ontario experienced huge flooding for the second time in three years. Contrastingly, in 2013 Lake of Ontario water levels were extremely low. According to specialists, teetering in hydrology is due primarily to climate change; more specifically three key aspects: precipitation over the lakes, evaporation over the lakes, and runoff (Molinos et al., 2015). As the earth heats up, more evaporation occurs and water levels decrease. High temperatures allow the atmosphere to hold more water, causing larger dumps of rain, thus increasing flooding. All this is a fancy way of saying that climate change causes fluctuating and unpredictable water levels (Rood & Gronewald, 2019). Definitely bizarre, but what does this have to do with loons?

A Minnesota study published in 2013 demonstrated the devastating impact climate change has on common loon nesting habits. Through advanced analysis techniques, researchers monitored the success of nests built 7-10 cms above the waterline. In 2 years, almost 37% of nests were unsuccessful due to flooding or stranding from rising water levels. That’s a high number of loons that go without producing young due to human-caused climate change (Windels et al., 2013).

Fortunately, common loons are real troopers and don’t give up without a fight. In the case of gradually rising water, loons were recorded to use cattails and bog mats for buffing up the nest edge, almost like how humans sandbag. In preservation efforts, conservation teams also provide loons with floating nest platforms to re-nest on (Rodomski, Carlson, & Woizeschke, 2014). In the case of disaster, loons were observed to re-nest up to 2 times before the end of the breeding season. Through sheer resiliance, 77 nests were rebuilt, of which 19 were successful (Windels et al., 2013).

So why don’t loons just build their nests higher away from the water and waddle a bit further? While loons are the top predator of a lot of smaller aquatic trophic systems, they don’t fare so well in the vast world of land predators. The adult loon itself has few known predators; notably large raptors, like eagles, hawks, and ospreys. By coming further out of the water, the adult loon has a higher chance of being spotted by a hungry predator. Refer to the GIF above displaying how loons move on land- Not a fair fight. Of even greater importance, however, is the susceptibility of the nestlings. When the adult common loons can’t protect their nests quickly from the water, and the nests are more visible to predators, nestlings and eggs become a quick snack for snapping turtles, gulls, crows, ravens, skunks, minks, etc (National Wildlife Federation, 2019). The same study showed that while flooding was significant, the largest number of nests were unsuccessful due to predation (Windels et al., 2013).

It seems loons just can’t win. Loon success decreases with rising water levels. It is hypothesized that loon survival rates will also decrease under low water conditions, as nests will be built further inland and loon nestlings will make a quick snack for bigger birds (Windels et al., 2013). Fluctuating water levels play a crucial role in loon conservation, and experts suspect that by the end of the century, the only place to see a loon may be on the back of a loonie (Audubon, 2019).

So what can you do? Firstly, you can spread the word. Inform your friends about declining bird populations. Since my original post, the Canadian federal election has concluded. However, you can still write letters to part leaders and people in power to elicit change. Additionally, individual actions matter. Reduce your emissions, reduce your single-use plastics, and vote with your dollars. Not sure where to start? Use this calculator to analyze your ecological footprint, and find where you can cut back. Do it for the common loon!

References:

Audubon (2019) Guide to North America’s Birds. (Internet): https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/common-loon

Audubon (2019) The Climate Report: Focal Species- Common Loon. (Internet): https://climate2014.audubon.org/birds/comloo/common-loon

Clifton, G., Biewener, A. (2018) Foot-propelled swimming kinematics and turning strategies in common loons. Journal of Experimental Biology: 221

Glacier National Park (2005). Common Loons in Glacier National Park. (Internet): https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/nature/upload/Citizen%20Science%20for%20Common%20Loon%20Monitoring%20Education%20Presentation.pdf

Livestrong (2019) The Average Height and Weight by Age. (Internet): https://www.livestrong.com/article/328220-the-average-height-and-weight-by-age/

Molinos, J., Viana, M., Brennan, M., Donohue, I. (2015) Importance of Long-Term Cycles for Predicting Water Level Dynamics in Natural Lakes. PLoS ONE 10(3)

Piper, W., Evers, D., Meyer, M., Tischler, K., Kaplan, J., Fleischer, R. (1997) Genetic monogamy in the common loon. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology. 41: 25-31

Pittaway, R., King, M. (2014) Loon ID in Fall and Winter. OFO News. http://www.jeaniron.ca/2014/loon2ID.htm

Radomski, P., Carlson, K., Woizeschke, K. (2014) Common Loon Nesting Habitat Models for North-Central Minnesota Lakes. Waterbirds 37(1): 102-117

Strong, P., Bissonette, J., Fair, S. (1987): Reuse of Nesting and Nursery Areas by Common Loons. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 51 (1): 123-127

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology (2010) All About Birds: Common Loon. (Internet): https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Loon/id

The Loon Project (2018) Do Loons Mate for Life? (Internet): https://loonproject.org/do-loons-mate-for-life/

The Science Behind Algonquin’s Animals (2005) Common Loon and Bird Migration Research in Algonquin Provincial Park (Internet): http://www.sbaa.ca/projects.asp?cn=303

The Scientific American (2019) Climate Change Sends Great Lakes Water Levels Seesawing. (Internet): https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/climate-change-sends-great-lakes-water-levels-seesawing/

University of Iowa Press. (2007). Common Loon Gavia Immer. Fifty Uncommon Birds of the Upper Midwest.

Windels, S., Beever, E., Paruk, J., Briniman, A., Fox, J., Macnulty, C., Evers, D., Siegel, L, & Osborne, D. (2013). Effects of water-level management on nesting success of common loons. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 77 (8).

Hi Shenade,

What an absolutely awesome blog! I really loved the clever title and beautiful introduction; they pulled me in to what became a really informative and well written discussion about these really neat birds. I remember watching loons in the Bowron Lakes when I was little and I tried (to no avail) to recreate their haunting calls. None of them ever responded to me – I just wanted to play Marco Polo too!

Their adaptations to living on the water are really cool. Those comically clumsy feet are really funny – as long as they aren’t stranded somewhere on land. You talked about some adaptations loons have for their lifestyle, and you mention that they rely on their excellent eyesight. Do you know of how their eyes are adapted to be as good underwater as they must be in the air? Perhaps the lens shape is different?

Your research topics were really interesting – I love how these birds are real troopers! They are very clever to have figured a way to protect their nests in cases of gradually rising water. While the conservation status of the Common Loon is most certainly of concern (as you state at the end), your conclusion does bring a little bit of hope. I appreciate how you closed out the post with a section on future considerations and a reminder on how we have the power to make change.

Again, awesome job and thank you for such a wonderful and interesting blog.

Samuelle

Hi Sam,

Thank you so much for all the kind words! I have similar memories with common loon calls. My brothers and I used to spend hours practicing the tremolo- I now realize we got no replies because we likely alarmed them all. Sorry loons!

This is a really interesting question. Our eyes are quite differently from those of diving birds. Our corneas are spherical and separate air and water into two refractive indexes. Since the cornea does so much work, our lenses pretty much focus on fine-tuning. Once we open our eyes underwater, the lens can’t compensate for the cornea and everything becomes blurry.

In diving birds, the lens does all the work. While our lenses have a flat shape, loons have a spherical shape. Their corneas are also flattened, allowing a refractive index that makes underwater vision VERY clear, but comes at the cost of the vision in the air, which apparently isn’t so great. Maybe that’s why there are so many cases of loon and grebe stranding? There are also some genome analyses that show a reduction in opsin genes to provide the common loon specifically with visual acuity in low light.

Here are two articles that might fill in any blanks I didn’t answer:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5921391/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982212010573

Again, I really appreciate all your encouragement. I’m so glad I was able to share the coolness of loons with someone else!

Cheers,

Shenade

Hi Sam,

Thank you so much for all the kind words! I have similar memories with common loon calls. My brothers and I used to spend hours practicing the tremolo- I now realize we got no replies because we likely alarmed them all. Sorry loons!

This is a really interesting question. Our eyes are quite different from those of diving birds. Our corneas are spherical and separate air and water into two refractive indexes. Since the cornea does so much work, our lenses pretty much focus on fine-tuning. Once we open our eyes underwater, the lens can’t compensate for the cornea and everything becomes blurry.

In diving birds, the lens does all the work. While our lenses have a flat shape, loons have a spherical shape. Their corneas are also flattened, allowing a refractive index that makes underwater vision VERY clear, but comes at the cost of the vision in the air, which apparently isn’t so great. Maybe that’s why there are so many cases of loon and grebe stranding? There are also some genome analyses that show a reduction in opsin genes to provide the common loon specifically with visual acuity in low light.

Here are two articles that might fill in any blanks I didn’t answer:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5921391/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982212010573

Again, I really appreciate all your encouragement. I’m so glad I was able to share the coolness of loons with someone else!

Cheers,

Shenade

Hey Shenade,

Interesting blog! I enjoyed the figure legends and I am sure that the Eagle gave that baby loon a better life somewhere else don’t worry :D… 🙁

You mentioned that due to climate change Loon’s habitats are shrinking, and specifically that their winter oceanic habitat would shrink by 75% which is a disturbingly large number! I was wondering if you had any other information on why exactly climate change is so destructive for their non-breeding habitat?

Also I appreciate how you included a relevant topic such as climate change into the blog and then tied it all together with a reminder to vote!

Well done,

Joel

Hey Joel!

In my mind, the loon nestling is living its best life with its adopted eagle dad. I’m glad someone else agrees. 😉

Great question! I focused a lot on the breeding habitat, but it turns out loons are pretty much in danger all year. One of the primary effects of global warming is increasing ocean temperatures which create “warm blobs” and promote the growth of toxic algal blooms. This is bad news for loons and other water birds. The dinoflagellates coat their feathers and prevent the loons from flying. Additionally, the coating can cause them to lose their waterproofing and become hypothermic. There was also evidence of hemorrhaging in the lungs of aquatic birds in algal blooms. Here’s that study: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0004550

And here’s one indicating the increase of toxic blooms with ocean acidification:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-018-0344-1?WT.feed_name=subjects_chemistry

Loons also rely heavily on pacific herring as a food source during the winter. While I can’t find a study linking the two, herring numbers have been decreasing for years as the juveniles can’t effectively function in higher temperatures. I imagine that a decrease in a main food source would also cause the loons some stress. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6034797/)

There are plenty of other detrimental factors associated with oceanic habitats that I could write a whole other blog about, but I’ve already written a novel so I’ll leave it at that. Let me know if you have any more questions!

Shenade

Hi Shenade!

Absolutely loved your blog! Almost as much as I love the sound of loon calls (I strongly agree with calling them “hauntingly beautiful”).

I have two questions: first, why do juveniles stay in coastal habitats so long after learning to fly, instead of migrating with their parents? Second, I was wondering what the success of the floating nest platforms provided by conservationists was. If successful, it would be interesting to see if nesting on floating platforms becomes more of a regular occurrence for these land-clumsy birds.

Thank you for putting links to voter registration and an ecological footprint calculator at the end! Hopefully this draws more people to conservation and climate change activism!

Melissa

Hi Melissa,

Thanks for taking the time to read my blog. Those are both great questions! I wondered about the first myself. It seems insane that both parents would invest so much time and energy into their young only to desert them once they hatch. I actually couldn’t find any reasoning for this. I’ve read numerous studies on migration, and the largest one (published in 2015) stated that it was an area that required more research.

https://bioone.org/journals/the-condor/volume-117/issue-4/CONDOR-15-6.1/Winter-site-fidelity-and-winter-movements-in-Common-Loons-Gavia/10.1650/CONDOR-15-6.1.full

I did stumble upon an article that claimed the adults often leave their young for a few hours and flock to other lakes. This had an interesting hypothesis that might also be applicable to the southward migration. A biologist at Chapman University put forward the idea that adult loons might be leaving the nest to reduce predation. Since they have such a distinct call and are such large birds, without the adults the chicks might have a better chance at staying hidden from predators. This wasn’t ever published, but he mentioned it in an interview that I’ll link below:

https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/today-in-strange-loon-news-why-do-loons-leave-their-chicks-home-alone

To answer your second question, there’s a study by a private biology company that claims these nesting platforms are extremely successful. Since they float, it completely eliminates the problem of nest flooding. Additionally, it increases re-nesting as the loon has to do very little work to re-nest. On one lake where 5 platforms have been installed, the nesting success has gone from 29% to 61%! Definitely worth more interest and funding to me.

http://fwcp.ca/floating-loon-platforms-double-nest-success-whatshan-reservoir/

Thanks for both your questions and support!

Shenade

Hey Shenade,

Awesome job on your blog! It was really well written and kept me engaged the entire read!

It is really cool how specialized these birds are to dive and move in water, but it really does seem that they got the short end of the stick on land. It’s so sad that they often mistake roads and parking lots for water and that they are likely unable to recover.

You mention that the Common Loon relies on its eyesight to catch their food. By saying this, do you mean that they have specialized eyesight compared to other similar birds?

Great job!

Danielle

Hi Shenade,

First of all, what an amazing blog! The way you made the “common” loon seem so peculiar and interesting was astounding! All of your embedded media provided depth which is a great bonus for the reader. Listening to the echo of the loon call brought me back to the time I would spend countless nights listening to the sounds of the roughed grouse. Overall great blog and I cant wait to read more from you!

Hey Griffin,

Thanks so much for the kind words! I’m so glad I could engage you in something a little outside of your regular interests. While the common loon and the ruffed grouse are really different birds, you’re right about the sounds. It has to be very quiet to hear the ruffed grouse, and it’s often in the eerily quiet moments that you hear the common loon calling as well. If you’re interested in learning more about other super cool birds, check out the rest of the blogs from my class at this link: http://wordpress.viu.ca/biol325/ .

Thanks again for your comment and encouragement!

Shenade

Hey Danielle,

Thanks for reading! I’m so glad you liked it.

Loons have very specialized eyes compared to other land birds. Since seeing long and far in the air isn’t as important, they’ve kind of compromised this for eyes that work wonders in the water. Loons have spherical lenses and flattened corneas, whereas land birds have eyes that more so resemble humans from what I’ve read (except with a larger visual field and the ability to see many more colours than we can). Loons are also said to have fewer opsin genes, which allow loons-and other diving birds- the power of seeing in low light. So yes, loons have very specialized eyes compared to and birds, but they’re very similar to other water birds in the sense that their eyes are completely adapted for finding food underwater!

Here’s an article that even further outlines their cool adaptations if you’re interested.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5921391/

Thanks again for your comment!

Shenade