Part 1: The Common Yellowthroat

Today I would like to discuss with you one of my favorite local species, the Common Yellowthroat. The Common Yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas) is a Wood Warbler within the family Parulidae and order Passeriformes (Ebird). There have been 30 different species of Wood-Warblers recorded on Vancouver Island, and out of those 30 species, only 10 species are commonly encountered (Ebird).

Identification and Description:

The Common Yellowthroat is a sexually dimorphic species; males and females look different (Thusius 2001). Both sexes are quite small, being only around 12cm from beak to tail (All About Birds). Males and females have rounded heads and slightly rounded medium-length tail feathers (Sibley). Both birds have a yellow throat and yellow undertail covert feathers which can vary in shade geographically.

The female warbler is typically an olive color, with a brownish head, a yellow throat, and a buffy belly. Compare this then to the male, while having similar features, also has a striking black mask around his eyes. The top of the mask is outlined with white feathers; this stands out against the brownish head.

Juvenile Common Yellowthroats resemble an adult female, and juvenile males have a very patchy mask. I included a photo (below) of a young male I got to band with the Vancouver Island University (VIU) banding station in 2019.

Calls and Songs:

Next time you are on a walk around Buttertubs Marsh in the spring, try to listen for the Common Yellowthroat’s call and song. Both the male and female make a very distinctive chedp call that is quite full in sound and does not follow a pattern with respect to the number of chedps given (Sibley). Males, however, have a more charismatic sound and sing a three high-pitched wichety-wichety-wichety song.

These birds are quite curious, so if you can hear their call, they might come in view if you make pishing sounds. This might be helpful to see Common Yellowthroats, as they prefer to be hidden in grasses.

What They Find Tasty:

Common Yellowthroats are insectivores, which means they primarily feed on insects (All About Birds). While they prefer to eat small insects, (such as ants, bees, flies, and beetles), they will eat bigger insects as well (such as dragonflies, damselflies, and butterflies). These warblers tends to remain quite low in grasses and shrubs, which allows them to find their prey (Sibley).

Where to Find Them:

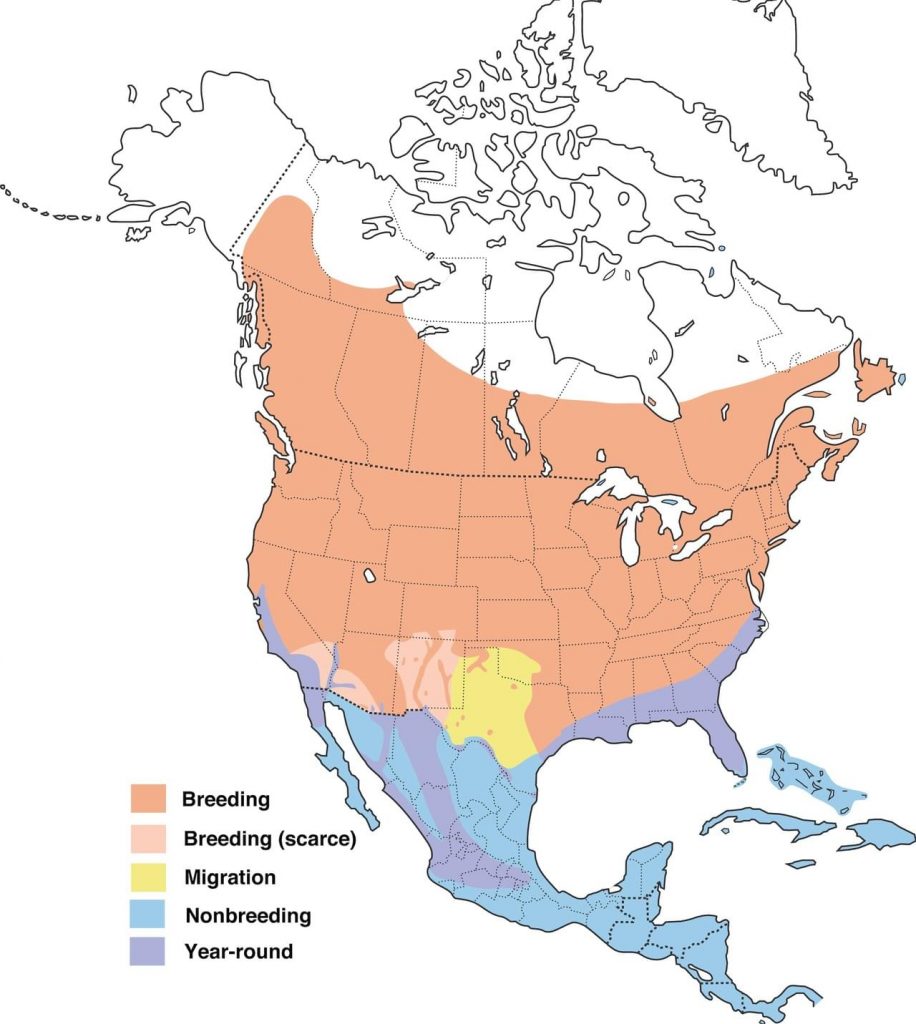

The Common Yellowthroat can be found all over North America (All About Birds). They tend to have a very small home range, and the smallest home range that has been recorded is 0.5 acres. This species breeds in almost all of Canada and the United States, and migrates to Mexico, Guatemala, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Nicaragua for the winter months (Figure 3). During migration, the Common Yellowthroat can be found in forests and backyards, although this is not their preferred habitat. Their preferred habitat is marshlands, and are one of the only warblers that like to nest in open marshlands! When they reach their final destination, they can sometimes be found in large foraging flocks of different species, but once they get settled, they prefer to forage on their own.

Behavior of the Common Yellowthroat:

Typically, this warbler is quite territorial within its home range during mating, and both males and females will defend their territories against other Common Yellowthroats (All About Birds). Females will attract mates by a signal of her fluttering her wings and calling with a fast series of chips. This signal will also attract other males, which she may choose to mate with behind her mates back (known as extrapair fertilization). However, Common Yellowthroats are only territorial of their home range until their chicks are born, as now feeding their offspring is more important than defending their territory.

Nesting and the Issue of Brood Parasitism:

The Common Yellowthroat makes its nests less than 3 feet off the ground on grasses and shrubs, or bulrushes and cattails in marshlands (Audubon). The nests are made by the female out of organic material such as pieces of weeds, bark, ferns, dead leaves, hair, and grass. Nests are formed into a cup-like structure, and sometimes they will even create a roof-like structure.

The female will lay between three to five eggs, but records have shown that she can lay up to six eggs. The eggs are creamy white in color, with brown and black spots. The female incubates the eggs for 12 days; the male bird will feed her on the nest during this time. After the eggs hatch, juveniles are fed by both parents and remain in the nest for eight to ten days. After they leave the nest, their parents will still continue to feed them until they learn how to forage for their own food.

Unfortunately Common Yellowthroats are often the victim of cowbird parasitism (Spautz 1999). Brown-headed Cowbirds are known brood parasites, as females will lay their eggs in other bird’s nests for them to take care of. Female brown-headed cowbirds time their egg-laying just right to lay their egg in the middle of the host bird’s clutch; they will also remove an egg to not raise suspicion by the female host. The host bird will incubate the egg until it hatches, and as the juvenile brown-headed cowbird is usually much bigger than the juveniles in its hosts nest, it will outcompete the other offspring for resources. This in turn might result in the death of some of the host bird’s offspring. Even though acceptance seems to be the most common reaction when the parasitic egg is discovered in the nest, there are a few different methods that the Common Yellowthroat parents might do to try and increase their nest’s success. One such method is for the warbler to desert it nest once they find the parasitic egg. The reason for this is to stop putting energy into a nest that most likely will fail from the parasitic egg. Another method is that they might try is to remove the parasitic egg from their nest. This does not always work however, as the female cowbird checks in on her eggs to make sure they are all still in the nest. If her egg is missing, she may destroy the host’s eggs in revenge.

If you would like to learn more about the Brown-headed Cowbird, I highly recommend that you read Marissa Wright-Lagreca’s blog post. If you are interested in learning about other species that are victims to brood parasitism I would recommend checking out Samuelle Simard-Provençal’s blog post on Warbling Vireos.

Conservation Status and What We are Doing to Help:

In general, the conservation status of these warblers is of least concern but that does not mean that their numbers are not dropping (All About Birds). The species has had a 38% decline from 1966 to 2014, and there has been an average decline of one percent of the entire population per year. The main reasons for this decline are the destruction of wetlands for agricultural and urban uses, increased use of pesticides, and lowered water quality. As this species primarily feeds on insects, pesticides are causing a decrease in the warbler population. There is currently no plan in place to stop the decline, but there is hope that the species might be able to benefit from waterfowl conservation efforts. As good practice, it important for us to not dump cleaners and other toxic solvents down the drain, as this can affect water quality, and to be mindful of these habitats, as many different species call it home.

Subspecies of the Common Yellowthroat:

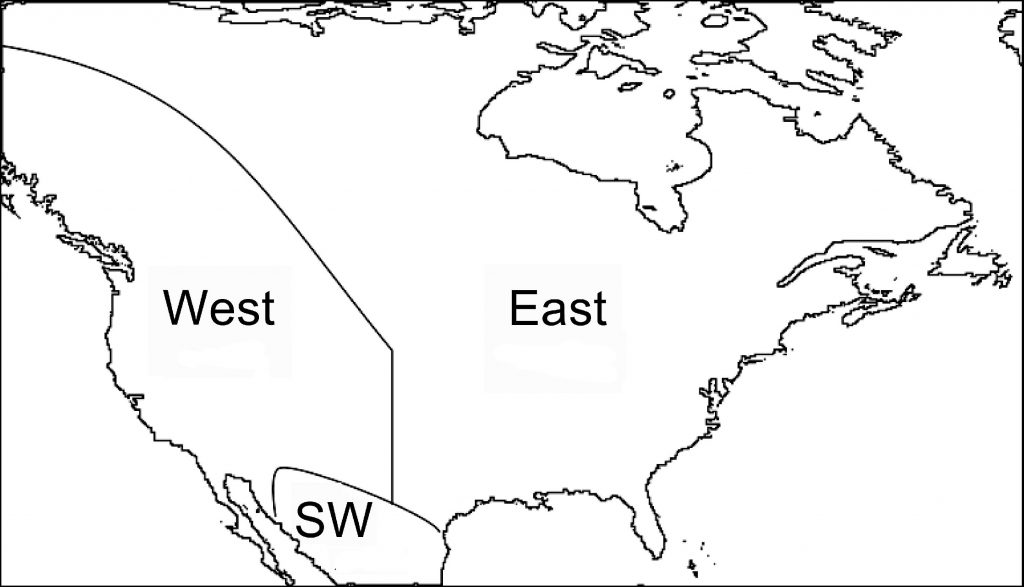

There are approximately 13 different subspecies of the Common Yellowthroat (Bolus 2014). Even though the subspecies are similar in appearance and behavior, through using genetic approaches, Common Yellowthroat subspecies can be separated into three different groups (Escalante et al. 2009). These three groups are the eastern, western, and southwestern groups (Bolus 2014). The eastern group is most related to the Hooded Yellowthroat (Geothlypis nelsoni) and the Altamira Yellowthroat (Geothlypis flavovelata), which can be found in South America. The western group however is more closely related to their Mexican relative called the Belding’s Yellowthroat (Geothlypis beldingi). The southwestern group is most related to the Common Yellowthroat, and not to any other species of the genus Geothlypis. While these subspecies are still considered to be Common Yellowthroats, they vary in genetic relatedness to the individuals we can find in Nanaimo.

A: Altamira Yellowthroat

B: Hooded Yellowthroat

C: Belding’s Yellowthroat

D: Common Yellowthroat

Two subspecies of Common Yellowthroats are facing challenges due to habitat destruction (All About Birds). One subspecies population from the San Francisco Bay region (western group) has declined between 80-95% in the last one hundred years, and another subspecies in Texas (eastern group) has declined by such an extent that a once abundant warbler was thought to have gone extinct. It is important for us to create practices that protect marshlands, as if we protect marshlands, we can protect many different species that live in these zones.

Part 2: Why it is Important to Wear a Mask:

Just like it important for us to wear masks when we go out in public, it is also very important for male Common Yellowthroats to wear one. Even though their mask won’t protect them from viruses, research has shown that the mask on the male Common Yellowthroat is very important in mate selection (Thusius et. al. 2001). Males with a larger mask had an increased social advantage, and were more likely to mate. These males were also able to participate in extrapair fertilizations, where males are able to have multiple mates in a breeding season. It was shown that males who have larger masks were able to father more offspring than males with a small mask. This could be due to the females recognizing that a smaller mask might indicate a younger male, as the Common Yellowthroat is not born with its mark.

young juvenile

juvenile

adult

Having a beautiful mask does not mean that the male will be a good father. Usually in animal behavior, the more “good-looking” a male is, the more care he will provide the offspring (also known as the good parent hypothesis), but this is not the case with Common Yellowthroats. In a study conducted by Daniel Mitchell and his colleagues, it was shown that male Common Yellowthroats provide less care to offspring if they have a more well-defined mask (2007). This is due to the fact that males with good masks will have more options in mating, and will try to mate with other females to increases their fecundity (or reproductive output). Males that have poorer masks will only be able to mate with one female, so they put more energy into rearing their young to increase their reproductive success.

In Memory of Wayne:

I hope you enjoyed learning about one of my favorite local birds. I would like to dedicate my blog to a very special bird that was well-known at the VIU Banding station. Wayne was a male Common Yellowthroat (banding code 2700 93399) who was always one of the first birds caught at the beginning of the banding season from 2013 until 2018. He was not good at avoiding the mist nets and was caught 46 times over this five-year time period, making him one the most recaptured birds at this station! Wayne has not been caught nor spotted since 2018 at Buttertubs Marsh, and we are fearing the worst for him. Although I never got to meet Wayne personally, I hope that by reading my blog you got to learn lots about Common Yellowthroats.

Literature Cited:

Arthur, N. (2020, December 09) Common Yellowthroat Meme [Photograph].

Bolus, R. T. (2014). Geographic variation in songs of the Common Yellowthroat. The Auk, 131(2), 175-185. doi:10.1642/auk-12-187.1

Common Yellowthroat. (n.d.). Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://ebird.org/species/comyel

Common Yellowthroat. (2020, April 30). Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/common-yellowthroat

Common Yellowthroat Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Yellowthroat/id

Demers, E. (2015, April 2). Wayne [Photograph]. VIU Bird Banding – April 2, 2015, VIU Bird Banding Club, Nanaimo, British Columbia.

Ebird. (n.d.). Bird Observations. Retrieved October 23, 2020, from https://ebird.org/barchart?byr=1900&eyr=2020&bmo=1&emo=12&r=CA-BC-AC%2CCA-BC-CP%2CCA-BC-CX%2CCA-BC-CV%2CCA-BC-NA&fbclid=IwAR2xcZK-LBRCsmm4Hcru8e31QX-SlzcS_6EPxS77migbr_OpLuKJc0xmOzk

Escalante, P., Márquez-Valdelamar, L., Torre, P. D., Laclette, J. P., & Klicka, J. (2009). Evolutionary history of a prominent North American warbler clade: The Oporornis–Geothlypis complex. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 53(3), 668-678. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.07.014

Houston Audubon (Producer). (2018, July 23). What is “Pishing”? [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRvdhovTgRo

Juvenile Male Common Yellowthroat 1 [Personal photograph taken in Nanaimo, British Columbia]. (2019, October 6).

Juvenile Male Common Yellowthroat 2 [Personal photograph taken in Nanaimo, British Columbia]. (2020, October 1).

Kayhart, R. (2012, May 13). Male and Female Common Yellowthroats. [Photograph]. Braddock Bay Bird Observatory, Hilton, New York.

McFarland, K. (2013, June 6). Common Yellowthroat Nest [Photograph]. Nests, Flickr, Woodstock, Vermont.

Mitchell, D. P., Dunn, P. O., Whittingham, L. A., & Freeman-Gallant, C. R. (2007). Attractive males provide less parental care in two populations of the common yellowthroat. Animal Behaviour, 73(1), 165-170. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.07.006

Perry, D. (2020, January 2). Altamira Yellowthroat [Photograph]. Altamira Yellowthroat, Ebird, Tamaulipas, Mexico.

Riffe, S. Common Yellowthroat Call [Audio]. (2016, May 8). Retrieved from https://www.xeno-canto.org/316669

Simard-Provençal, S. (Producer). (2019, November 3). In Memory of Wayne [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0jzHVrNNK9U&feature=youtu.be

Simard-Provençal, S. (2020, September 12). Adult Male Common Yellowthroat [Photograph]. Nanaimo, British Columbia.

Sibley, D. A. (2016). Common Yellowthroat. In The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America (2nd ed., p. 371). New York, NY: Scott & Nix.

Spautz, H. (1999). Common Yellowthroat Brood Parasitism and Nest Success Vary with Host Density and Site Characteristics. Studies in Avian Biology, 18, 218-228.

Strycker, N. (2003, June). Common Yellowthroat [Photograph]. Oregon.

Thusius, K. J., Peterson, K. A., Dunn, P. O., & Whittingham, L. A. (2001). Male mask size is correlated with mating success in the common yellowthroat. Animal Behaviour, 62(3), 435-446. doi:10.1006/anbe.2001.1758

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (Producer). (2013, March 4). Common Yellowthroat Song [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ECVC3tS_G4U

Van Norman, A. (2016, October 1). Belding’s Yellowthroat [Photograph]. Belding’s Yellowthroat, Ebird, Baja California Sur, Mexico.

Voaden, N. (2015, March 10). Hooded Yellowthroat [Photograph]. Hooded Yellowthroat, Ebird, Distrito Federal, Mexico.

Young Juvenile Male Common Yellowthroat [Personal photograph taken in Nanaimo, British Columbia]. (2020, October 1).

Ziegler, D. (2009, July 26). Common Yellowthroat feeding Juvenile Cowbird 1 [Photograph]. Common Yellowthroat, Flickr, Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Hi Madi,

Lovely blog:) Looks to me like you truly love these bright little warblers!

I was intrigued about there being 29 wood warbler species recorded on the island. I cross-checked eBird records with the website you cited, and I think you might be able to improve the accuracy just a little bit! The Avibase checklist may be mildly sketch… it also includes BCCH as a VI bird, but I don’t think there has ever actually been an accepted record.

The research you included was interesting. Mate selection pressures are always neat to study. Do you know any of the statistics behind the paper you reviewed? How much of an advantage do males with larger masks have? Do the researchers look into the difference in number of offspring produced or number of successful copulation events?

Thank you for sharing your love for these fun birds. Wayne would be honoured, I’m sure.

Cheers,

Sam

Hi Sam,

Thank you for reading my blog!

I looked into the number of species from the family Parulidae that have been spotted on Ebird for Vancouver Island, and the consensus that I am getting is that there are 30 different species, with an additional 3 hybrid species seen. I’ll make sure to update the species seen with a more reliable link source!

To answer your question about statistics and how they determined if the mask was successful or not, the researchers used both DNA fingerprinting and microsatellite analyses to determine who the juveniles belonged to. As COYE only have “one” mate that they take of after copulation, it is hard to determine that the male taking care of the nest is actually the father (due to extrapair fertilization). Due to this reason, the researchers took blood samples from both the parents and juveniles from 46 broods, and then determined paternity of the young in each nest. The mask size between male individuals varies almost 2x, with the smallest mask being 195mm2 and the largest mask being 376 mm2, and it was also discovered that mask size increased with age. A larger mask also did increase extrapair sires. The number of extrapair fertilizations from males with larger masks was statically significant (p = 0.003), but I cannot find the number of offspring sired in extrapair fertilizations of small mask males vs. large mask males.

The genetics behind this paper was insane!

Hope that answers your questions!

Madi

Hi, Madi,

Interesting report/blog. I enjoyed reading it, hearing the tidbits of inform. & sounds and I liked the information on the masks & relations to mating. Nice little “in memory of”.

Keep masks on & stay safe!

Johanne

Thanks Johanne for reading my blog! It means a lot to me!

Sending hugs,

Madi

Hey Madison,

I really enjoyed reading your blog! I found it so interesting about the mask size and how that effects the male’s involvement in the raising of the young. Thank you for sharing the video and story about Wayne, I love how you mention he was not good at avoiding the mist nets.

I was wondering if you had come across any recent research regarding the cowbird parasitism? Is there ways for the COYE to prevent the cowbird from placing the egg in their nest? I find it so amazing how smart some birds can be!

Danielle

Hi Danielle,

Thanks for your lovely comments about my blog! The question you asked me was quite interesting, and I have spent some time trying to find information on it! There doesn’t seem to be a clear cut answer to it unfortunately, but I did find a recent paper! In this paper (2014), COYE were studied in Iowa, and it was discussed that COYE nests are parasitized less when they are in marshlands with a greater number of RWBL nests, increased number of forb plants nearby, or if the nest is more concealed, but this paper also says that some of their results contradict other recent papers.

One of the reasons why COYE might not have any real defenses against BHCO is because BHCO used to be only on plains, and followed bison. When forests became more cleared due to deforestation, the species was able to spread its range to new areas that it wasn’t previously found in, and I suspect has created a co-evolutionary arms race with COYE and other songbirds.

Here is the link to the paper I am talking about: https://academic.oup.com/condor/article/116/1/74/5153089

Hope this helps a bit, hope you have a great weekend!

Madi

Hi Madison. Is the masks on individual birds dissimilar enough to be used as a method of identification? If they are could a high resolution camera be used in known migratory routes to identify birds as they stop to rest? Would be interesting to know more about the individual birds habits and they areas that they visit without having to net them.

Hi Trevor,

Thank you for reading my blog!

Many birds preform different moult strategies, so this means that they will grow new feathers at different points in their life. This is how bird banders can determine how old a bird is, as they can compare the state of the birds feathers to previous records for that bird. Here is a link to what bird banders look for in COYE to determine its age: http://www.migrationresearch.org/mbo/id/coye.html Because the feathers can be shed and/or damaged, feathers themselves are not a good marker to determine individuals apart from one another.

There are a few different ways that we can track birds without continuously re-catching them. Some researchers will do both the metal band (with the 9 numbers) on one leg and then add plastic coloured bands on the other leg. This makes it so you can a ID a particular bird form a distance with binoculars, as you will have recorded the plastic band information when you did the original processing of the bird. Here is a link to why colour banding is important: http://bloom.bio/news/2019/5/17/color-bands-why-they-are-important

Another way that researchers can track a birds movement is by using MOTUS nano tags. These tags are so small they have been put on insects, like dragonflies and butterflies! How they work is that radio-transmitters are attached to the bird, and they are then tracked by radio telemetry. Each nano tag releases a different signal, so the signal can be matched to an individual. The only issue is that these nano tags are super lightweight, which means they have a small battery and a small battery life. This means that the tag either has to be replaced, or you are only going to collect data while the tag is has a battery life, but at least we can answer questions about migration that we might have not known about before! Here is a link to COYE that were tagged in the US:https://motus.org/data/tracksMap?t=14671&t=14674&e=2013-01-01&l=2020-12-31&s=17000

Hopefully this answers your questions!

Madi

Hi Maidson,

Great blog!

What was your experience like learning to hold the birds for tagging? Were the females or males more feisty or calm?

Thanks,

Wendy

Hi Wendy,

Thanks for reading my blog, it means a lot to me!

Learning how to bird band is a super cool experience, it is something I heard never heard about before I started university. I feel like in general, the more ‘scary’ birds to bird band are raptors (like hawks and owls). I myself haven’t banded any raptors, as I’m a bit of a novice/beginner bird bander. I don’t think the sex really makes them more feisty, but some species are more feisty than others! For example, chestnut backed chickadees always seem to be some of the most angry birds I have handled, even though they are one of the smallest!

Hope that answers your question!

Thanks,

Madison

Hi Maddy,

I use to think the Wilson’s Warbler was my favourite warbler, however after reading this blog I may need to change my mind. I had a question regarding the mate selection and masks. Because the least attractive males stay longer and help the rearing of the young, could this lead to a preference for those with lighter masks? It made me wonder if having a colourful mate will become less important if this means they will have a mate who can help provide for the young thus increasing their chances of survival. What are your thoughts on this?

Thanks for the super interesting read,

Eden

Hi Eden,

Thank you for reading my blog!

There are actually selective pressures on colour, because even though they might not be the most faithful mate, its a honest signal of health! I think the female is hoping that by mating with a healthy male, he will be able to provide more resources because he is able to provide them for himself. It is also a cue that he is older, and maybe the female thinks that this means he has experience rearing young in the past.

Here is a paper I found discussing how the colour in COYE masks and bibs affects mate selection: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00873.x

Hope this helps!

Madi

Hi Madison,

Enjoyed your blog- I am not able to pick out warblers, not fast enough with binoculars, but the bird call is very distinctive, I will have to walk the Buttertub Marsh trail again .

Are there yellow throats in Saskatchewan?

Thanks,

Kaye

Hi Kaye,

Thank you for reading my blog! There are common yellowthroats in Saskatchewan, but they should have migrated south by now. It looks like there have been sightings of them in the Waskesiu area in July. They like to be around water, so any areas with cattails might be a good place to start to look! Here is a link to ebird, where a lot of birders will input data, maybe it will help your search! 🙂 https://ebird.org/region/CA-SK?yr=all&m=

Sending Hugs,

Madi