PART I: Introduction

Easily recognizable and found in great abundance, the Red-Winged Blackbird is the most widely-known of the 5 blackbird subspecies in North America. Flying in flocks of up to the millions and flashing their bright red epaulettes, the feisty Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) is a beautiful bird to behold and is even more fascinating below the surface.

Description and Identification

As the name suggests, Red-Winged Blackbirds are easily identifiable by their brightly coloured epaulettes (shoulders). This feature is only present however in breeding males of the species, used to threaten competition and attract the attention of their brunette female counterparts. Non-breeding males lack completed red patches and instead sport a black, almost scaly look in colouration. (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

Though the red shoulders of the Red-winged Blackbird are recognized as a staple trait, males may often be confused with the Tricoloured Blackbird, a similar but more localized subspecies of Blackbird. The main indicator that the bird seen is truly a Red-winged, is the yellow band below the epaulette, while the band appears white in their subspecies cousin. These two species can often be seen flocking together on the west coast of Canada.

Female Red-wing Blackbirds are streaky in colour, with a yellow hue around their beaks. Females are found to be slightly smaller than males, with the species ranging between 32 to 72 grams in weight, and 17 to 23 centimetres in length. (Griff & McIntyre, 2009) However, the size and proportions can vary between different subspecies.

Red-winged Blackbirds have slender, conical beaks which they use to collect seeds and hunt insects from the marshland they inhabit. They have a stocky build and a wingspan of 31 to 40 centimetres. Belonging to the Order Passeriformes, and like many of the songbirds, the Red-winged blackbird has Anisodactyl Feet, with three digits in front and one in the back. This model of feet is designed to perch on reeds and twigs, as well as allows them to run or bounce across open fields, which is very beneficial to ground foragers such as the Red-wing. They even have the ability to hop backwards while foraging which is referred to as “double scratch”. (Griff & McIntyre, 2009) Red-winged Blackbird eggs are typically blue-green and covered in dark spots.

Many people will recognize a Red-winged Blackbird song without realizing what bird it comes from. An everyday background trill, the song of a male consists of several introductory notes followed by a harsh “kon-ka-reeee”. There is also a common “Chek” call that is used to communicate flight to nearby birds. Lastly, the Red-winged Blackbird is able to make an alarm call that is a single high pitched note, trailing slightly down in pitch. It will use this to alert other blackbirds of the presence of nearby predators. (Sibley, 2016)

Distribution, Habitat and Nesting

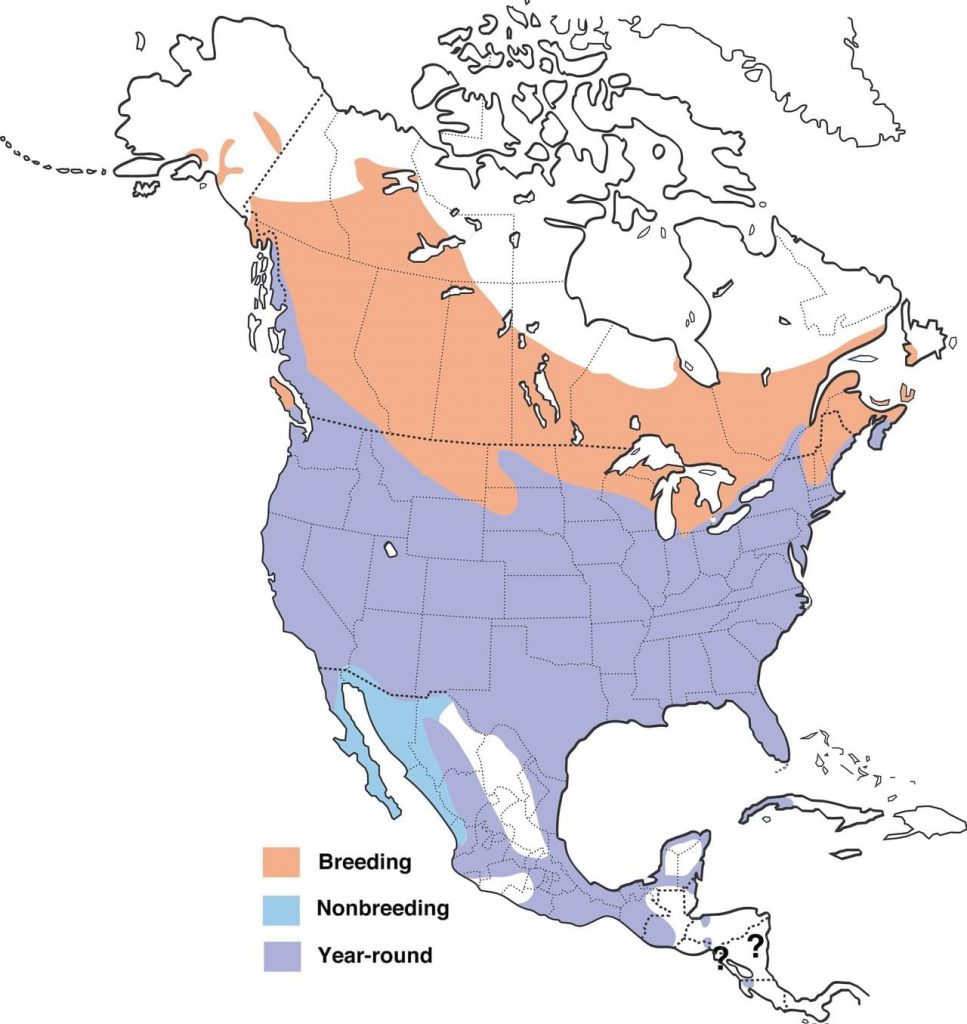

The Red-winged Blackbird can be found throughout North America over the course of a year. They predominantly inhabit the United States year-round but make their way northbound for the warmer breeding season. Their migration is known to be one of the first signs of spring in Canada. Red-winged Blackbirds spend the breeding season in wetlands but fresh and saltwater. They are also known to inhabit hayfields, meadows and even wooded areas along waterways. In fall and winter, they congregate in millions, with similar species, in agricultural fields, and grasslands. The factors behind their chosen habitat include the abundance of nesting materials, food sources, and even the types of birds that live in the neighbourhood. (Griff & McIntyre, 2009)

Fun fact: Red-winged blackbirds travel as many as 800 miles south for the winter!

Red-winged Blackbirds build their nests low, near the ground or water surface among the dense vegetation. The nest consists of varying weaved plant material, filled with wet leaves and decaying wood. Next, the nest is plastered with mud and then finally lined with fine, dry grass. When the nest is complete, it measures approximately 4 to 7 inches across and 3 to 7 inches deep. This nest is simple but durable and effective, being adaptable to whatever resources are at hand. (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

Behaviour

The Red-winged Blackbird is a highly polygynous species, with up to 15 female partners at a time, though on average this is closer to around 5 partners per male. During the breeding season, males are extremely aggressive and territorial, even known to attack larger animals such as people and horses.

Red-winged blackbirds may have up to three broods per partner per year. Females are the main contributor to building nests and choosing the nest location within a male’s designated territory. Prior to and throughout the breeding season, male Red-winged Blackbirds can be seen sitting on a high perch over their territory and singing as a way of displaying dominance and sexual prowess. (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

Females lay three to five eggs and incubate them for approximately 11 to 13 days. The young red-wings then stay in the nest for 9 to 12 days. Both Female and Male Red-winged blackbirds protect the nest from predators during this time. It is even seen that other neighbouring Red-winged Blackbird males will go out of their way to defend a nest in another male’s territory. This interesting, perceived altruistic behaviour shows a more cooperative side of the otherwise highly aggressive males. (Olendorf, Getty & Scribner, 2004). Red-wing males often sound an alarm before divebombing their enemies from behind. Fearless, they repeat this for as long as necessary, often staying with the predator long after they have fled, proving they are not to be messed with. (Griff & McIntyre, 2009)

Fun Fact: Young Red-wings are capable of swimming in short distances while adult Red-wings cannot!

Conservation Status

Red-winged blackbirds are abundant in North America and also are a widely-studied species. They are considered of Low-Concern, although the Red-wing Blackbird, like many bird species, is still threatened by many things. (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

The main threat to a Red-wing is habitat loss due to the drainage of wetlands for development and agriculture. As with many other birds, red-winged blackbirds are vulnerable to pesticides. Predators of adult red-winged blackbirds include hawks and owls. Their eggs and young may also be preyed upon by predators such as raccoons, mink and other birds such as the marsh wren. The Red-winged Blackbird has adapted to this nesting threat through the placement of nests over water. (Griff & McIntyre, 2009)

PART II: Current Research – Defensive Strategies

Defense as a Team: Cooperative Rivals

Red-winged Blackbirds are known for being highly territorial and aggressive, persistent and brave, going after predators that could swallow them in one bite. However, one of the most common conflicts seen leading up to, and during the breeding season, is the conflict between male Red-wings. It is common to see males staking their territory to each other by raising their epaulettes and practicing in aggressive song. This behaviour translates to sexual selection power with the females and often territories are marked clearly before females have even migrated fully over. Once nesting has occurred however, a shift in attitude occurs where neighbouring males become protective of each other’s young.

It was observed by researchers that once mates and territories were established, there became a non-biological bond between neighbouring families, where males would come to the aid of other males and defend their young just as aggressively as their own. Through the study, it was hypothesized that this was an act of reciprocal altruism, as there were no additional external motivators observed, such as resource trading, or sired offspring (biological relation to that of the neighbouring male).

It was a simple understanding that the males protected the young of those who were in the most danger, even at the risk of their own young being temporarily less protected. This “golden rule” was then passed down through multiple breeding seasons and generations. This overall was seen to cause high nesting success for contributing males. (Olendorf, Getty & Scribner, 2004).

Defense Against Brood Parasites

A brood parasite is a bird that lays its eggs in another bird’s nest, relying on other birds to take care of their young. Sometimes when doing this, the parasitic bird will destroy the host’s eggs in the process. This can be extremely destructive and have lasting damages to the local population of competing birds. A relevant example of a local brood parasite is the Brown-headed Cowbird.

In order to defend against brood parasitism, the Northern Yellow warbler developed a way to communicate between females of the species and warn them of the presence of birds such as the Cowbird. They make a distinctive alarm sound when Brown-headed Cowbirds are near called a “seet” call. (Goldman, 2020) This “seet” call is unique to the cowbird and alerts nearby warblers to return to their nest, preventing egg transfers from occurring.

During a study where researchers observed yellow warblers and this behaviour, they noticed the consistent presence of Red-winged Blackbirds in the area. It was known that the two birds often nested in similar areas, and were seemingly less territorial with each other, but, the researchers soon noticed that the Red-winged Blackbirds were actually in fact responding to this “seet” call.

As cowbirds prey upon Red-wings as well, it was theorized that there is a mutualistic relationship between Red-winged Blackbirds and Yellow warblers. When working together against a common enemy, it was seen that both species experienced less brood parasitism when nesting near each other. Yellow warblers gave early warning calls of nearby Brown-headed Cowbirds, and in response, Red-wings fought off the cowbirds with their aggressive behaviour. (Lawson & Hauber, 2020)

Conclusion

In conclusion, Red-winged Blackbirds are well populated and found all across North America. These spirited and determined birds travel hundreds of miles each migration and they can adapt to most climates given their well-rounded diet and nesting needs. Red-winged blackbirds work tirelessly to keep up their species survivability, juggling many partners and defending not only their young but that of each other. They even became bilingual in order to gain from yellow warblers and protect themselves from brood parasitism. This is a clear sign of a successful bird whose intelligence and resiliency has led it to succeed in the Law of Natural Selection

References

Christopher McPherson, XC602542. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/602542

Goldman, J. (2020, April 13). Red-Winged Blackbirds Understand Yellow Warbler Alarms. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/red-winged-blackbirds-understand-yellow-warbler-alarms/

Griff, D. (2009). Red-winged blackbird (1066035505 810256428 T. McIntyre, Ed.). Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.hww.ca/en/wildlife/birds/red-winged-blackbird.html

Lawson, S., & Hauber, M. (2020, March 31). Yellow Warblers’ special cowbird alarm alerts blackbirds. Retrieved November 19, 2020, from https://www.birdwatchingdaily.com/news/science/yellow-warblers-special-cowbird-alarm-alerts-blackbirds/

Martin St-Michel, XC179966. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/179966.

Olendorf, R., Getty, T., & Scribner, K. (2004). Cooperative nest defence in red-winged blackbirds: reciprocal altruism, kinship or by-product mutualism?. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 271(1535), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2003.2586

Red-winged Blackbird Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Red-winged_Blackbird/overview

Sibley, D. (2016). Red-Winged Blackbird. In Sibley birds west: Field guide to birds of western North America (2nd ed., p. 434). New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Simon Elliott, XC597738. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/597738.

Hey Kiera!

Great blog! I really enjoyed the visual aspect and the different shapes to the pictures. That video of the Red-winged Blackbird attacking the geese was very cool. I kept waiting for the geese to eventually fly away! Did you happen to read anywhere about why they have the ability to hop backwards while foraging? Also I found the fun fact about the young being able to swim quite interesting. Was there any reason for why this is?

Thanks for sharing with us!

Danielle G

Hey Danielle,

Thanks for commenting! My research on the “double – scratch” only spoke of them being capable of it due to the shape of their feet, however, I can elaborate on what this technique means. With each hop forward, RWBL grabs the leaf litter with their feet, and with each hop backward, releases the leaf litter to expose the ground and grub beneath. Hope that gives you a little more context.

As for the young, they cannot swim far and do not do it on purpose. They cannot fly for the first 10 days of hatching and sometimes they can fall in the nearby marsh. When they do, they can swim and hold onto a nearby cattail if needed since the option of flight is not available to them. This is also likely a natural response for them since their species nests on wetlands primarily. It is likely that the feathers of the adult RWBL absorb water at a rapid rate, making it impractical for flying adults since it would heavily weight them down.

Hope that answered your questions!

Cheers,

Kiera Brown

Hi Kiera,

Nice blog. Brood parasitism is always really interesting!! Do you know how affected BWBL are by BHCO? I would imagine that a little YEWA might suffer a greater magnitude of nesting failure due to BHCO parasitism compared to RWBL.

Thanks for sharing your love of RWBL.

Cheers,

Sam

Hey Sam!

Thanks for commenting! RWBL are more successfully targetted by the BHCO than the YEWA; however, they are less affected by the inclusion of cowbird nestlings. A study that I will link found that

Cheers,

Kiera Brown

Haha sorry, my bad, accidentally pressed reply and you cannot edit comments after the fact.

To finish off my comment. They found in the study that the foraging rate of the parents and the amount of time spent with the young remained unnotably changed. They only noticed a slight increase in begging from the RWBL nestlings but they grew healthy in the same amount of time regardless. They even found that despite the BHCO nestlings constantly begging, the host parents fed them the same amount as their own young. The relationship between the RWBL and the YEWA is so beneficial because the YEWA significantly decreases the number of successful attempts from the BHCO and the RWBL fights back against the BHCO, protecting the YEWA in return.

Hope that answered your question!

Cheers,

Kiera Brown

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003347203921683

Hi Kiera,

Great Blog! The video you included of the Red-winged blackbird attacking the geese was super interesting and was a very effective way of showing their aggressive territorialism.

Their nesting behaviour was super interesting to read about, especially when you mentioned that other neighbouring RWBL will actually protect nests besides their own. You mentioned earlier that they are very polygynous, does this affect the RWBL’s ability to protect their nests since the males have several mates at a time and therefore possibly several nests?

The brood parasitism research you mentioned was also super fascinating. I love that somehow the RWBLs have picked up on the meaning behind the Yellow Warbler’s “seet” call.

Thanks for sharing!

Madeline

Hey Madeline,

Thanks for commenting! Female RWBL are significantly less territorial to their fellow females, and therefore they often will put their nests close to each other in the most ideal location within a male’s territory. So each male RWBL will have a cluster or two of nests rather than all of them scattered around his territory. This allows males to have an easier time watching over all the nests in that area.

Hope that answers your question!

Cheers,

Kiera Brown

Hi Kiera,

Loved your blog post! It was very informative! I had no idea how neat this species was. I particularly enjoyed the video footage of the Red-winged Blackbird aggressively dive bombing the geese. To think that these little guys are brave enough to attack much larger species!

It was also very interesting to read about the mutualistic relationship formed between the Red-Winged Blackbird and the Yellow Warbler in order to work against the common enemy. The Brown-headed Cowbird is a well known brood parasite and has been known to affect many species including the Orange-Crowned Warbler (my bird), so I really enjoyed learning about the formation of a mutualistic relationship in attempts to work against the enemy. Very well done!

Gabrielle

Hi Kiera,

Thanks for the great post! When I was in Ontario, they were one of my favourite birds, since they were so common and easy to recognize by both sight and sound! It’s cool to learn more about species that you like superficially but don’t know their full story, I never knew they were such feisty little birds! One question that I have is regarding their territorial behaviour. During the breeding season, do the flocks disperse into smaller groups with only one male allowed, or are the territories simply for nesting purposes and they still remain together for foraging?

Have a great day!

Adam

Hey Adam!

Thanks for commenting! RWBL are territorial all through the breeding season, designating a certain territory before the female birds have even entered the area from their migration down sout! Females will often flock together during this time but males are very independent. Once nesting has occurred males tend to relax a lot more on boundaries and during the nonbreeding season, the group flocks and migrates together as a large group. THey even flock with other similar species, forming groups in the thousands.

Hope that answered your question!

Cheers,

Kiera Brown