When we think about birds, we often consider the most spectacularly coloured ones or the most unbelievable predators. Last summer, I found myself mesmerized as I watched what appeared to be a small russet potato dart across a rocky beach at Nitinat lake in July 2020. His small eyes gleaned intensely as he searched for his next snack, seemingly impartial to my presence. It was at that moment I realized one of the true beauties about birds, their sheer diversity. His plumage was far from spectacular (obvious by my potato description), he did not appear palatable in any way; nor did he look like an apex predator. Instead, he had one magnificent quality that trumped all of those traits, he was bloody cute. With the help of the internet, I soon discovered that I was looking at the Least Sandpiper— a Chad after my own heart! Understanding the outstanding beauty of my fine feathered friend, I invite you to sit back, relax, and enjoy learning about a bird that may not have previously made your top ten coolest birds list.

Let’s get to know these feisty little taters.

Identification and Description:

The Least Sandpiper (Calidris minutilla) is a spectacularly small shorebird. In fact, it is the smallest shorebird in the world, standing at an average of 5.1-5.9 inches (All About Birds; Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency). They belong to the Family Scolopacidae, and further classified within the Order Charadriiformes. While these birds can be distinguished from certain sandpipers by size (The Upland Sandpiper average being 11.0-12.6 inches (All About Birds)), others such as the semipalmated Sandpiper are more difficult to differentiate, as they average 5.9-7.5 inches (All About Birds). In particular, Least Sandpipers and Semipalmated Sandpipers can be distinguished by feet colour, as semipalmated have black feet.

a)

b)

Figure 1: a) Adult Least Sandpiper in nonbreeding plumage (Photo by Ian Davies). b) Adult Least Sandpiper in breeding plumage (Photo by Evan Lipton).

Least Sandpipers sport a fairly drab plumage, regardless of the season (breeding vs. non-breeding). They have a white belly surrounded by a gradient of brown-grey plumage, that spans from their head to their tail tips. In addition to this, they also have a long black beak with a slight down curve, and dull yellow-green legs with disproportionally long toes. Just imagine a combination of rubber ducky yellow and Shrek green, that should accurately depict their leg colour. During their breeding season (discussed later), they display similar colouration and design. The key differences include the disappearance of grey, followed by the addition of slight yellowish hues and a rusty speckling on their back (All About Birds).

A delicate song to put you to sleep … NOT:

Least Sandpipers love to trill. Trills are, a type of sound production that involves a broader range of frequencies that are combined to create an echo-like sound. During breeding season, the males (and sometimes females) sing a sequence of fairly high-pitched trills. When they’re not trying to get lucky, their call is still high-pitched, but becomes more of a creep sound, with trills mixed in (All About Birds)

Sound 1: The call of a Least Sandpiper. Note that each call contains multiple frequencies, which is what causes the echo-like trill (sound recorded by Thomas Graves).

These guys indeed like to move it move it:

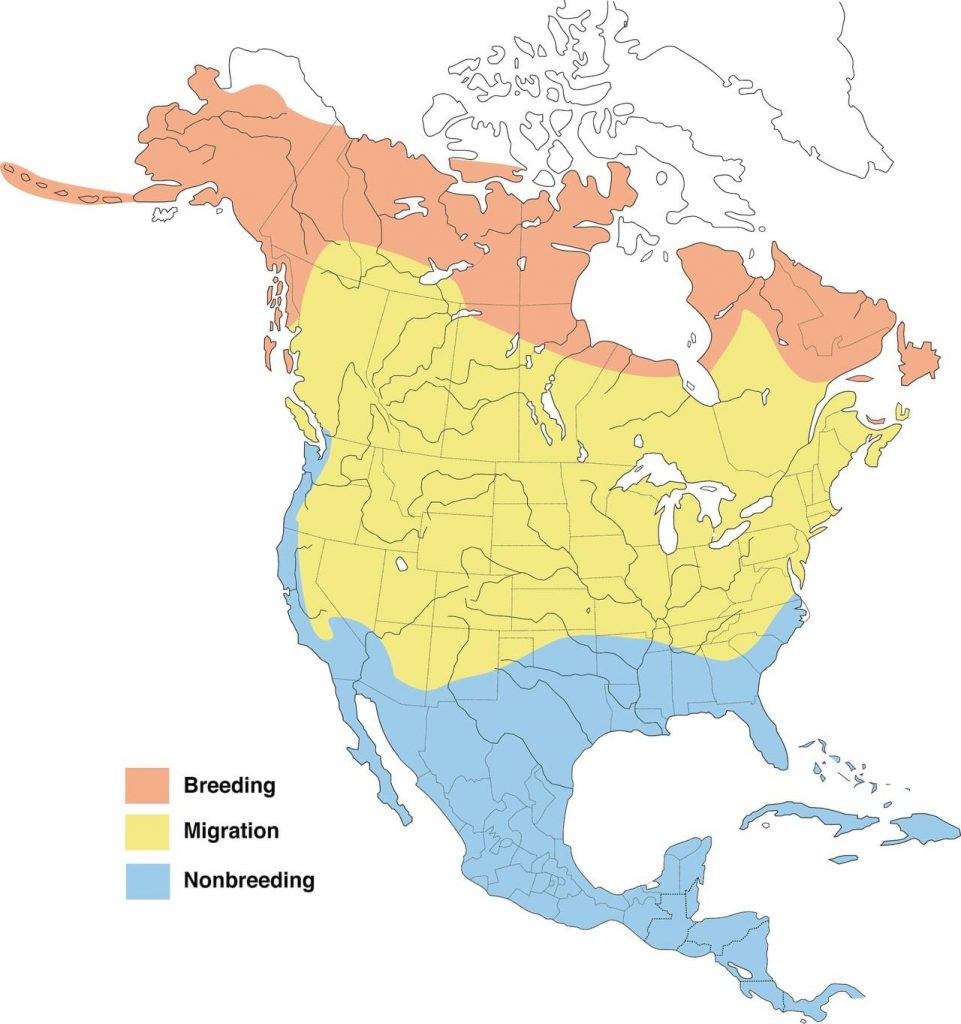

For being such small individuals, these birds are fierce migrators. They travel massive distances every year, and presumably not just for fun. Shown below, we can see a distribution map of Least Sandpipers in North America. It is suspected that the Eastern populations fly between 1800-2500 miles non-stop over the ocean to arrive in South America; while the Western population follow a more modest crawl along the coast or near interior (All About Birds). If that didn’t just blow your socks off, then I know you are definitely a liar.

These competitors can be seen nearly anywhere in North America. Although, it should be noted that they prefer wet areas such as mudflats, marches, swamps, and shores due to feeding habits (Audubon).

Figure 2: Geographic distribution of Least Sandpipers in North America (All About Birds).

Soooooo, what’s for dinner?

Least Sandpipers thrive on a healthy diet comprised of various benthic invertebrates, above ground insects, and occasionally wetland seeds (All About Birds; South Dakota Birds). Like most shorebirds, Least Sandpipers are probers, meaning they dart around wet, muddy areas searching for prey. Their long bill allows them to penetrate the mud and extract hidden invertebrates. An incredibly fascinating fact about these birds is that they use a special technique called ‘surface tension prey transport’ (Rebuga, 2008). This involves the rapid opening and closing of the jaw, which carries a droplet of water containing prey items up the bills for consumption (Estrella et al, 2007). This techniques works due to the unique physical properties of water, which apparently are the bane of invertebrate existence.

Figure 3: “I found a snack!” Adult Least Sandpiper feeding at Nitinat lake, July 2020 (Photo by James Ogihara-Kertz).

Where does sexy time fit in, and where does it happen?

Finally, the good stuff … Wait shit, did I say that out loud? Least Sandpipers are known to breed in the spring (mid-May to early-June), similar to most other avian species (Bouglouan). They migrate fairly far north to breed, one of the southernmost location being Sable Island, Nova Scotia (Miller, 1983). Interestingly, when mating season arrives, the males migrate approximately a week before the females do. This buffer time allows males sufficient time to prepare their lovely nests for inspection, in hopes of wooing the lady of their dreams (or any lady, really). This is actually a very innovative and simplified version of tinder. The males are stripped of their ‘swiping’ privilege while the females are allowed unequivocal decision making.

Least Sandpiper breeding occurs predominantly on dry ground near bodies of water to protect the eggs and allow easy access to feeding. Female generally lay 3-4 eggs (Miller, 1979; All About Birds) with an incubation period between 19-23 days. The female generally deserted quite quickly, leaving the male to protect his young, usually until they can fly, around 14-16 days later (Audubon). The juvenile birds display plumage somewhat similar to the breeding plumage of adults, Except they are more brightly coloured and display some additional rufous colour (Sibley, 2016; All About Birds). They also sport a whitish supercilium (eyebrow area). As previously discussed, the plumage in Least Sandpipers is monomorphic, so to differentiate male and female juveniles you would have to monitor a dimorphic characteristic (such as bill length).

Figure 4: Juvenile Least Sandpiper. Notice the white supercilium right above the eye (Photo by Alix d’Entremont).

Save the shorebirds!!!

While Least Sandpipers are very common throughout North America and are listed as a low concern for conservation, it does not mean that we should neglect them in any way. Shorebirds have been steadily declining over the years due habitat destruction veiled as urbanization. A 2016 North American study reported a 70% decrease in shorebird populations since the 1970s, which is absolutely mind blowing (Nature Conservancy Canada, 2018; North American Bird Conservation Initiative, 2016). According to a 2012 study by Connell lab of Ornithology, it estimated 700,000 Least Sandpipers in North America (Save Coastal Wildlife). Don’t let this fool you into thinking that they’re perfectly safe. Consider a 1% decrease in population, that would result in a 7000-indiviual loss. Amplifying this to a 10 year steady decline would mean 70,000 Least Sandpipers in 10 years…

So, I just know that you’re all at the edge of your seat wondering what you can do. Yes you! Becoming aware of the habitat destruction occuring around you is a wonderful first step. Even with a quick google search I was able to find some interesting links to the Okanagan Wetlands Strategy as well as a document on the importance of the Wetlands of the Southern Interior Valleys. I realize the second article is outdated (2004), but urbanization of wetlands and population growth are constantly growing, so it proves to remain relevant regardless.

Sidebar: Audubon has a super interesting visual model of how climate change and temperature increase will affect Least Sandpiper range. It even lets you look at different temperature increases! It really helped you understand how drastically temperature increase would affect the world; I highly recommend sneaking a peek.

What exactly do we think we’re doing in THEIR swamp?

The year is 2050, I am no longer as plump as I once was whilst preparing for migration. The food supplies are simply not what they used to be. Furthermore, my favourite swamp has just been urbanized by those awful, awful humans. Shorebird populations have been decimated across Canada. Different species of shorebirds have put aside their differences and have united with the hopes of sweet retribution. Why us, what did we ever do to deserve such a hellish punishment? I leave this as my last cry for help before I begin my arduous journey to the promised land, with the hopes that someone may read this and call to arms, for us.

– An internal monologue from Jeff, the Least Sandpiper

Figure 5: A picture was included in the bottle, presumably this is Jeff. Since there was no photographer listed, I guess I have to take credit (Photo by James Ogihara-Kertz).

I received this immensely moving message from a bottle floating in the ocean that was undeniably from the future. I was so touched that I decided to make it my mission to research shorebird habitat destruction, with the hopes of fulfilling Jeff’s wishes. A united call to arms from the human race.

As you read above, Least Sandpiper populations may not be in imminent danger, but we need to conserve those numbers by protecting the very land they flourish on. Human have been ravaging the earth for many years now. Our greed has now turned its eyes to the precious wetlands, swamp, and mudflats, that house so many wonderful species, including our beloved Least Sandpiper. Studies have reported that across Canada and the United States, approximately 85% of wetlands have already been destroyed and replaced by agricultural expansion (Scientific American). Due to the efforts of many conservation groups the rate has greatly slowed, but slowing the rate is no longer sufficient; it needs to be completely stopped!

Least Sandpipers, among other shorebirds, rely heavily on abundant wetlands during migratory periods as stopover locations to refuel energy stores. In the case of Least Sandpipers, they must travel north up thousands of miles to breed, and then back down those same miles to their non-breeding grounds. Maximizing the acreage of wetlands available is critical as it not only allows for greater freedom during migration, but also ensures that specific regions are not overexploited. Tofino is home to one such gem, The Wah-nah-jus Hilth-hoo-is mudflats. Since 1997, the majority of The Wah-nah-jus Hilth-hoo-is mudflats have been within the boundaries of the Tofino Mudflats Wildlife Management Area (WMA) (WHSRN). However, regardless of conservation efforts, Dunlin, Western Sandpiper, Least Sandpipers, and Short-billed Dowitchers have experienced negative trends regarding counts (Drever et al, 2016). These negative effects were characterized as a reduction in feeding due to higher rates of vigilance towards humans, fleeing, and distancing (Frid and Dill, 2002). Due to our presence, the shorebirds were not able to maximize their efficiency, leading to not enough fat stores, late migration, and potentially death. But we want Tofino, don’t we? And obviously if we want it then it MUST be ours. And once again, our greed to capitalize on the beauty of nature will take its toll on Least Sandpipers and other precious species.

Restoration of wetlands sounds like a fantastic idea, right?! Yes and no. It’s a wonderfully thoughtful idea to restore what we have so greedily taken. However, studies have reported that the efficacy of this is questionable. It appears as though ‘restoration’ of wetlands is simply someone slapping a goddamn band-aid on the swamp and calling a day. The ecological processes that have been disrupted can take decades to fully recover (now that, is a big ol’ yikes). What’s more, the beta diversity was lower in restored wetlands vs. natural ones (Anderson and Rooney, 2019). Beta diversity refers to the ratio of regional (in this case migratory birds) to local residents. That means that even though the wetlands had been restored, migratory birds would not return as readily. The evident solution is presented on a silver platter, rather than putting all of our effort in restoration of wetlands, we should focus on conserving what we still have, and have restoration as a secondary goal.

On a scale of 10-10 how much have these devilishly handsome birds stolen your heart?

Personally, it’s the easiest 11 out of 10 that’s ever left my lips. Thanks so much for checking out the blog, I hope you enjoyed reading it. I encourage you to follow up, do your own research, and learn even more about these amazing birds. Feel free to leave any question or opinions in the comments below!

Literature cited:

Anderson, D.L.; Rooney, R.C. (2019). Differences exist in bird communities using restored and natural wetlands in the Parkland region, Alberta, Canada. Restor. Ecol., 27(6), 1495-1507. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1111/rec.13015

Audubon. (n.d.). Guide to North American Birds: Least Sandpiper. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/least-Sandpiper

Bouglouan, N. (n.d.). oiseaux-birds: Least Sandpiper. Retrieved November 17, 2020, http://www.oiseaux-birds.com/card-least-Sandpiper.html

Brandon, M.B. Nature Conservancy Canada. (2018). Shorebird populations declining. Retrieved November 17, 2020. https://www.natureconservancy.ca/en/where-we-work/manitoba/news/shorebird-populations.html

Davies, I. (2016, September 28). Nonbreeding adult Least Sandpiper [Photograph]. Georgia. Macaulay Library. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Least_Sandpiper/media-browser/64822761

d’Entremont, A. (2014, August 23). Juvenile Least Sandpiper [Photograph]. Nova Scotia. Macaulay Library. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Least_Sandpiper/media-browser/64822741

Drever, M.C.; Beasley, B.A.; Zharikov, Y.; Lemon, M.J.F.; Levesque, P.G.; Boyd, M.D.; Dorst, A. Monitoring Migrating Shorebirds at the Tofino Mudflats in British Columbia, Canada: is Disturbance a Concern?. Waterbirds, 39(2), 125-135. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.039.0203

Estrella, S.M.; Masero, J.A.; Pérez-Hurtado, A. (2007). Small-prey profitability: Field analysis of shorebirds’ use of surface tension of water to transport prey. The Auk, 124(4), 1244-1253. https://doi.org/10.1642/0004-8038(2007)124[1244:SPFAOS]2.0.CO;2

Frid, A.; Dill, L. (2002). Human-caused Disturbance Stimuli as a Form of Predation Risk. Conserv. Ecol., 6(1), 1-16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26271862

Graves, T.G. (2019, September 2) Least Sandpiper Call [Audio file] Morro Bay, CA. https://www.xeno-canto.org/496351

Jiménez, A.; García-Lau, I.; Gonzalez, A.; Acosta, M.; Mugica, L. (2015). Sex Determination of Least Sandpiper (Calidris minutilla) and Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri): Comparing Methodological Robustness of Two Morphometric Methods. Waterbirds, 38(1), 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.038.0103

Lipton, E. (2016, May 16). Breeding adult Least Sandpiper [Photograph]. Massachusetts. Macaulay Library. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Least_Sandpiper/media-browser/64822761

Miller, E.H. (1979). Egg Size in the Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla on Sable Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. Ornis. Scand., 10(1), 10-16. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.2307/3676338

Miller, E.H. (1983). Habitat and breeding cycle of the Least Sandpiper (Calidris minutilla) on Sable Island, Nova Scotia. Can. J. Zool., 61(12), 2880-2898. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1139/z83-376

Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management; Ministry of Water, Land, and Air Protection. (March 2004). Wetlands of the Southern Interior Valleys. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/species-ecosystems-at-risk/brochures/wetlands_southern_interior_valleys.pdf

Okanagan Basin Water Board. (December 2019). Okanagan Wetlands Strategy. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.obwb.ca/newsite/wp-content/uploads/rpt_wetlands_final_singles_1_1.pdf

Rubega, M.A. (2008). Surface tension prey transport in shorebirds: how widespread is it? Ibis, 139(3), 488-493. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1997.tb04663.x

Save Coastal Wildlife. (June 11, 2019). Shorebirds in decline. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.savecoastalwildlife.org/save-coastal-wildlife-blog/2019/6/11/shorebirds-in-decline

Scientific American. (July 9, 2006). Wetlands Update–Has Preservation Had an Impact?. Retrieved November 19, 2020, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/wetlands-update/

Sibley, D.A. (2016). Least Sandpiper. In Sibley Birds West: Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Knopf, A.A. [ed], New York, NY. p. 143. https://www.sibleyguides.com/product/sibley-field-guide-birds-western-north-america-second-edition/

South Dakota Birds. (n.d.). Least Sandpiper. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.sdakotabirds.com/species/least_Sandpiper_info.htm

State of North America’s Birds. (2016). Oiseaux. Birds. Aves. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.stateofthebirds.org/2016/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/SotB_16-04-26-ENGLISH-BEST.pdf

Syilvia Duckworth. (2011, January 15). Je suis une pizza, Charlotte Diamond [Video file]. Retrieved November 20, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wxystpPE1xU

Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. (n.d.). Least Sandpiper. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.tn.gov/twra/wildlife/birds/waterbirds/least-Sandpiper.html

The Cornell lab of Ornithology. (2019) All About Birds: Least Sandpiper. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Least_Sandpiper/overview

The Cornell lab of Ornithology. (2019) All About Birds: Semipalmated Sandpiper. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Semipalmated_Sandpiper/overview

The Cornell lab of Ornithology. (2019) All About Birds: Upland Sandpiper. Retrieved November 17, 2020, https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Upland_Sandpiper/overview

Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network. (2013) Tofino Wah-nah-jus Hilth-hoo-is Mudflats. Retrieved December 1, 2020. https://whsrn.org/whsrn_sites/tofino-wah-nah-jus-hilth-hoo-is-mudflats/

Hi James,

Very funny blog! Very entertaining. I wasn’t going to read it all today, but the intro had me invested. I had no idea that their dinners could be so… bilingual. These little taters have definitely stolen my heart!

Do you know if there have been any documentation of LESA hybrids with other peeps? Just out of curiosity. My dream is to band one… or do any shorebird banding for that matter.

Thanks for sharing your love of these little shrexy birds!

Cheers,

Sam

Hi Sam!

Thanks so much for taking the time to read my blog, I’m glad you enjoyed the goofs and gaffs I snuck in. I looked into specifically LESA hybrids and I couldn’t seem to find any evidence of hybridization. Apparently these guys like to keep the genes T I G H T. That being said, I didn’t come up empty handed. I found some other sandpiper hybrids that have been documented and studied enough to earn their own name.

Cox’s sandpipers are the most well documented, and are a hybrid between specifically male PESA and female CUSA. I’m not as to why it is that specific combination, but mitochondrial DNA tests were performed showing that it matched CUSA (mitochondrial DNA comes from the mother). These guys were first recorded in Australia in 1955. Due to hybrids being so rare this was most of the data that I could find. Some other “hybrids” have been seen and speculated on, but nothing solid. Cooper’s sandpipers are supposedly hybrids between CUSA and SPTS, and were also seen in Australia a few decades ago. Maybe the Australian peeps are just built differently? Last but not least I found some information suggesting DUNL and WRSA hybrids have been observed in Cape Sable, right here in Canada!

If you’re interested, here are the articles I was looking at.

https://capesablebirding.wordpress.com/2016/03/09/hybrid-calidris/

https://www.birdguides.com/articles/ornithology/coxs-sandpiper-the-species-that-never-was/#

I hope I was able to shed some light on your question!

James

Hi James!

Great blog, I didn’t realize these little guys could pull on my heart strings like they did! Finding Jeff’s message in a bottle must have really inspired you to look into their conservation, and that leads me to wonder… do you think he wrote that message with his feet or with his bill?

I like that you included all that information about the conservation efforts for their habitats. Did you happen to find any information about conservation efforts specifically for the Tofino Wah-nah-jus Hilth-hoo-is Mudflats? Just curious if there are any plans to preserve that habitat since its such a heavily trafficked area for humans as well as migrating birds. It seems that it would be difficult to implement effective conservation efforts while still satisfying the tourism industry.

Thanks!

Haley

Hi Haley,

I’m happy you enjoyed the blog! Great question, after some research I have updated the section regarding the Tofino Wah-nah-jus Hilth-hoo-is Mudflats. It seems as though there have been conservation efforts in place already, namely the Tofino Mudflats Wildlife Management Area (WMA). This comes as good and bad news. The good news is that the ecosystem is more or less safe from destruction so long it resides within the WMA boundaries. The bad news is that regardless of conservation effort, due to the sheer presence of humans, we have seen declines in many shorebird species (including LESA). :^(

Not all is lost though! Every year, Tofino residents have begun celebrating the arrival of these shorebirds (Tofino Shorebird Festival) during their migratory stop in hopes to raise more awareness of the site’s importance. What’s even cooler is that the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) acquired First Nation, Federal government, and municipal input and agreed as a group to designate the area as a WHSRN site in May 2013, WOW! For sure steps in the right direction are being taken, hopefully they are taken in time.

If you’re interested in looking into it more, here are the articles I used!

https://naturecanada.ca/news/tofino-wah-nah-jus-hilth-hoo-is-mudflats-celebrating-a-vital-link-in-a-chain-of-sites-for-migratory-birds/

https://bioone-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/journals/waterbirds/volume-39/issue-2/063.039.0203/Monitoring-Migrating-Shorebirds-at-the-Tofino-Mudflats-in-British-Columbia/10.1675/063.039.0203.full

https://whsrn.org/whsrn_sites/tofino-wah-nah-jus-hilth-hoo-is-mudflats/

https://raincoasteducation.org/what-we-do/events/tofino-shorebird-festival/

I hope that answers your question!

James

Hi James!

I have to agree with you an easy 11/10. These little guys are heart stealers. I loved your blog, it was funny, knowledgeable, as well as kept me interested and on the edge of my seat the whole time.

I actually had a question similar to Haley’s in regards to the conservation efforts in tourism destinations. How do you think they would be able to enforce a conservation area in a place that has so much human activity? Do you think that they would strictly enforce conservation areas for migratory birds, or would it be simply another sign that sadly many people tend to ignore?

Julia

Hi Julia,

Thank you so much for taking the time to read and comment on my blog! I didn’t have much space to elaborate on the Tofino mudflats in my blog, so I’m glad you are asking these great questions.

As I mentioned Haley, further research showed me that the Tofino Wah-nah-jus Hilth-hoo-is Mudflats are actually within conservation boundaries, and have rapidly become a highly protected area within the last 20-30 years. The problem with the decline of shorebirds is that it is not actually due to habitat loss, it is more based upon the presence and proximity of humans. The amazing news is that there is actually the Tofino Shorebird Festival every year that I mentioned to Haley, and it looks like many people come with high powered scopes to watch shorebirds. The scopes mean that there is much much less human disturbance (yay), and the festival could be a venue to spread much needed awareness to seasonal tourists.

Since LESA tend to migrate and breed during mid-May to early-June, I feel as though it shouldn’t be too difficult to restrict certain areas from access during heavy migratory periods northwards. Especially with the ample protection the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN) is employing. The difficulty arises when they migrate back south around August, as that is peak tourist season in Tofino. I think the awareness that has already been spread will be impossible to ignore, and I refuse to believe that it is a lost cause!

Feel free to check out the articles I linked for Haley, I included the Tofino Shorebird Festival in there!

Thank you again for your comment,

James

Hey James,

Your blog and Jeff’s note have inspired me to take up arms to save this distressed potato we have come to know and admire. Also could there be any better name for that little bodacious sucker than Jeff?! I think not…

Anyways great blog, and I was just wondering when and how long these guys stick around our shoreline for before they continue onwards? In other words, does their arrival coincide with peak tourism in places such as Tofino?

Cheers,

Brae

Hey Brae,

Honestly Jeff’s parents could not have chosen better, he and his name will be an ever-standing icon to all shorebirds, I’m glad he inspired you too!

Great question, I found a study done in Tofino that stated northward migration occurred during April/May, while southward migration occurred between early August all the way to October. I’ve also attached a Tofino tourism report that estimated visitor volume per month. Peak months include predominantly July and August, but taper off fairly significantly in both direction (5000-10000 less visitors in June and September). To answer your question, they’re northward migration avoids peak tourism, but their southward migration potentially coincides with the absolute highest volume month, August. I believe most shorebirds tend to stay at stopover sites for a week at most.

I couldn’t find any research on the topic, but I would be curious to know if there could be a trend of shorebirds beginning to stay in the north for longer periods. Opting to migrate southward closer to October, rather than August.

If you’re interested in looking into it more, here are my sources.

https://bioone-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/journals/waterbirds/volume-39/issue-2/063.039.0203/Monitoring-Migrating-Shorebirds-at-the-Tofino-Mudflats-in-British-Columbia/10.1675/063.039.0203.full

https://tourismtofino.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Economic-Impact-of-Tourism-in-Tofino-2018-4Mar2019.pdf (page 8 in the PDF has the graph)

Thanks so much for taking the time to read and comment on my blog,

James

Hi James,

I loved your blog post! The little potato has definitely stolen my heart. I really appreciated how you added so much comedy to your writing, it definitely captured my attention and had me at the edge of my seat. Your blog regarding the Least Sandpiper was very informative, I appreciated how you included lots of information regarding the conservation I learned a lot about this species. Jeff’s little monologue definitely pulled at my heartstrings. Very well done!

Gabby

Hi Gabby

I’m so happy you enjoyed the blog! I really enjoyed researching and writing about the conservation of LESA as well as other shorebirds.

Thank you so much for reading my blog and commenting,

James

Hey James,

I knew I could come to your blog for an entertaining post and I was certainly not disappointed! I love your ability to use humour as a way to spark interest in an otherwise unassuming species, although I will say I have always loved sandpipers since I saw the conservation efforts been had at the beaches I would visit growing up.

I enjoyed the clip of them trilling but I was wondering what other sounds they may make, maybe one when they are alarmed? Aside from writing notes in bottles of course. Also just a suggestion, I would define benthic invertebrates since some people may have never heard of that turn for molluscs and such. Otherwise truly great post!

Cheers,

Kiera Brown