Introduction

Have you ever played the game spot the difference? I am sure you have. But on the odd chance you have not, let me explain. It’s easy: you are provided with two pictures, and the goal is to identify the differences. I am sure you remember when I said it was easy, right? Well, that statement was true until I learned of nature’s masquerading bird species. Puzzle enthusiasts meet your new challenge: the Willow Flycatcher.

Identification

The Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii), a member of the Tyrannidae family, is a passerine not known for its physical features but rather for its distinct sound (Bird Web). When trying to identify the Willow Flycatcher, a common scenario will prevail; you will observe a slender bird with a peaked crown perched upright on a branch, and you instinctively will believe the bird is a flycatcher. When you notice it dart from its position to capture an insect, you will note its brownish-olive colour and white throat. And, if you get an excellent view, a bicoloured bill and two-white wing bars may come into focus. With a field guide in hand, you will feel confident that you can identify this bird, that is, until you realize that there is a handful of flycatchers who all look nearly identical. In a final attempt, you will find the bird again to get a better look; you will notice it has an incredibly faint white eye ring, and BINGO, you will trust this is enough to get a correct identification (All About Birds). But, despite your best efforts, you will remain baffled: is the bird a Willow Flycatcher or an Alder Flycatcher?

Due to its striking resemblance to the Alder Flycatcher, you must recognize the Willow Flycatcher’s song for a confident identification. The best-known pneumonic to distinguish this bird’s vocals is “fitz-bew,” so if you are ever out birding and hear a faint sound, similar to someone sneezing, you are likely in the presence of a Willow Flycatcher (All About Birds). This song is distinctively different from the Alder Flycatchers, whose song can be described as a frog’s croak, “rreee-BEEP” (All About Birds).

Willow Flycatchers’ songs are short, often lasting for less than a second, but you will hear males endlessly repeating this song when attempting to attract the attention of a female. So, gentlemen, take note, the Willow Flycatcher has found the secret to captivating ladies’ attention! While females often make soft whit calls, they seldomly sing “Fitz-bew” (All About Birds).

HABITAT AND DISTRIBUTION

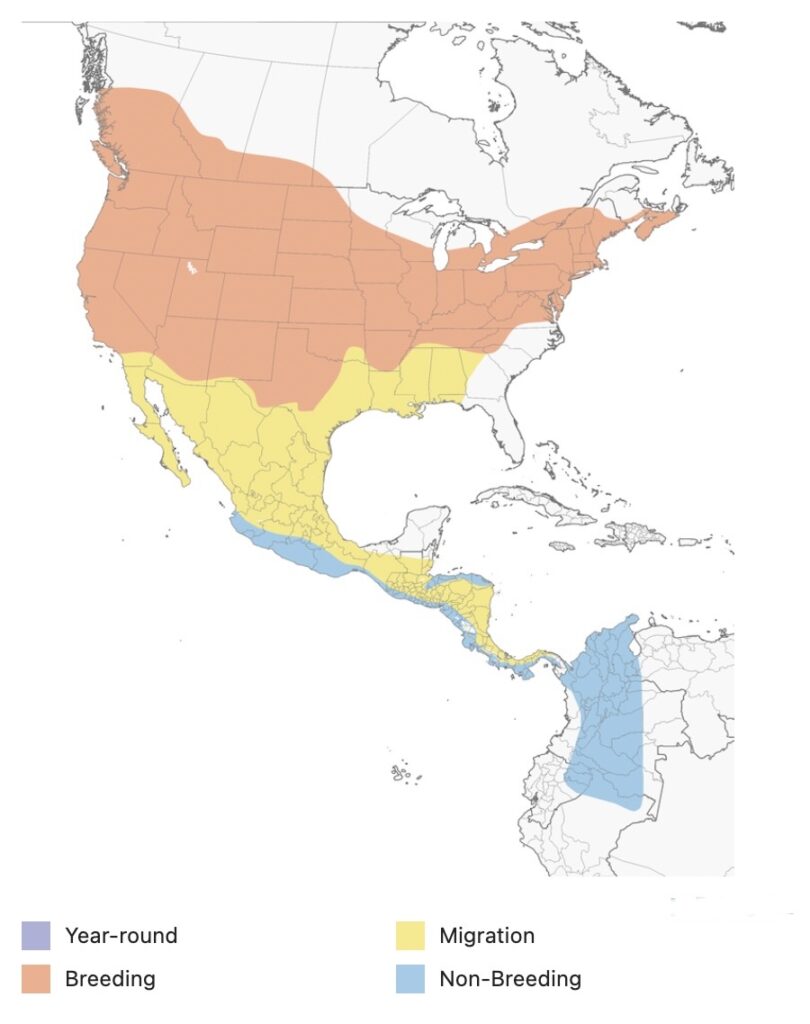

Willow Flycatchers are long distant migrants who call the Americas home. Starting in mid-May, Willow Flycatchers will be observed across central British Columbia, portions of Southern Canada, and the United States (Animal Diversity Web). They favour shrubby areas near standing water or streams during the breeding season. As their same suggest, they utilize trees and shrubs such as willow thickets, box elders, and dogwood trees (All About Birds). If you are hoping to spot a flycatcher, this season is your best chance!

Each year, Willow Flycatchers return to the same site or nearby areas to breed. As a result, these birds are incredibly territorial. Often, claiming a place much larger than required, the male will sit on the highest perch available, threatening others who come near with a combination of tactics. When an intruder looms, they will flick their tail, spread out their tail feathers, and flick their wings. If their snappy movements are not enough, this small bird is prepared to chase away any enemy (All About Birds). Of course, don’t forget, this bird has a sinister sneeze!

After the summer months, Willow Flycatchers are ready to embark on their extended vacation to escape the higher altitudes, drab weather, and insufficient resources. Jealous? Me too! Willow Flycatchers will travel to Mexico and Central America; some enthusiasts will even move as far as Colombia. Here, they will find high-altitude tropical clearings or woodland edges (Animal Diversity Web). Identifying these birds during this time is much more challenging as their song is seldomly heard.

Feeding Behaviour

Willow Flycatchers are primarily insectivores, eating anything from wasps, flies, beetles, and moths. As aerial foragers, Willow Flycatchers will sit perched on a shrub, often atop a high branch, waiting for their prey to pass. When they spot their target, they quickly swoop down from their position, attempting to catch the insect with their beaks (Animal Diversity Web). It can be challenging to catch their moving prey, but the lovely crunch is worth it! In addition, Willow Flycatchers sometimes snack on berries, such as dogwood or blackberries, to supplement their diet (Audubon).

Breeding Behaviour

Willow Flycatchers are often monogamous throughout the breeding season. However, in threatened populations, such as the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, polygyny, in which one male mates with multiple females, has been observed (Kus et al., 2017). Though Willow Flycatchers’ breeding behaviour is not fully understood, there is a belief that during courtship, pairs will use their alluring song and the fun game of chase to establish a mate (All About Birds).

In the world of the Willow Flycatchers, the females are responsible for building the nest. Using vegetative materials, including grasses and other plant materials, the females will build a nest 2-5 feet off the ground in trees such as the willow. For upwards of a week, she will exert energy and effort into building a nest about three inches across and three inches tall. This nest will be where she incubates her clutch of 3-5 eggs (All About Birds).

Despite all her hard work, brood parasitism by the Brown-headed Cowbird can result in her nest’s failure. Sneaking into the nest, the Brown-headed Cowbird will damage or remove the future mother’s eggs, replacing them with its own. Sadly, the Willow Flycatcher will unknowingly invest all her resources into the offspring of the Brown-headed Cowbird (Brodhead et al., 2007).

Conservation

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (ICUN) classifies Willow Flycatchers as a species of least concern. Now, what does that mean? The Willow Flycatcher is not a species of concern as its overall population numbers remain high (ICUN Red List). Phew! Except, this classification only mirrors part of the story.

The American Breeding Bird survey acknowledges that the species population has declined by approximately 25% between 1966 and 2019, and today this trend continues (All About Birds). In some areas, this bird is considered common. However, in the western United States, the Willow Flycatcher is in rapid decline, and it has been identified as an endangered species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Due to the bird’s favoured areas association with rivers and streams, habitat loss and overgrazing have disrupted the species’ livelihood (National Park Service). Magnifying this issue is the devious behaviours of the Brown-headed Cowbirds.

Fun facts

- The Willow Flycatcher and Alder Flycatcher are now considered sister species, but before 1973 they were recognized as the same species due to their indecipherable appearance, overlapping habitats, and feeding behaviours (Novitch et al., 2015).

- Flycatchers are unlike many songbirds. When Willow Flycatchers were raised by scientists, without exposure to their parents, they still vocalized their species’ song, “Fitz-bew.” Therefore, instead of learning their songs, their songs are innate (Kroodsma, 1984).

- The oldest recorded Willow Flycatcher was at least eleven years old. Its first capture was in California in 2001; its final recapture was in 2010 (All About Birds).

Current Research

In recent decades, alarm bells have been ringing regarding Southwestern Willow Flycatchers. In California, populations are at an elevated risk as fewer than five hundred pairs remain within the state. At the hands of humans, their wetland habitats have been destroyed by agricultural grazing and modified hydrology. Despite the implementation of large-scale restoration projects in Sierra Nevada, Willow Flycatchers have yet to return to the restored habitats (Schofield et al., 2018). Of course, I know what you are thinking: you would love for your house to be re-vamped and modernized, so what is the Willow Flycatcher’s hesitation?

Birds, especially passerines, choose their territory based on habitat quality and conspecifics (Muller et al., 1997). As acknowledged, a high-quality habitat has been established in the Sierra Nevada, indicating conspecifics, which mean other members of the same species, are missing. The habitat selection theory suggests territorial birds, such as the Willow Flycatcher, should deliberately avoid crowded locations, favouring areas such as the vacant meadows in California (Ward & Schlossberg, 2004).

However, in theory, you may love the idea of escaping the city, moving out to the mountains, and isolating yourself from the chaos occurring in a city’s core. Although, this move would come with substantial risk. When you live in the city, you are surrounded by establishments that secure you with your daily needs, such as groceries and prescriptions. However, when you move off the grid, you are solely responsible for acquiring the necessities for survival, and birds recognize this risk. Despite the competition being a threat, when other birds occupy the area, incoming birds perceive this as a sign of a resourceful habitat (Muller et al., 1997). Consequently, re-establishing a once-thriving habitat is a tremendous undertaking.

A recent study used conspecific broadcasts to encourage Willow Flycatcher’s settlement in unoccupied, recently restored meadows. Researchers in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California choose areas with dense willow cover to install automated broadcast systems. In essence, they introduced a speaker that played the Willow Flycatcher’s song, “fitz-bew,” and their calls, “whit.” These pre-recorded sounds were played at regular intervals and included vocals from other known species in the area. As a result, they discovered Willow Flycatchers were attracted to the meadows that broadcasted bird songs; they were observed in 35.75% of fields with the broadcast system and only 5.3% of meadows without the broadcast system. Though this study cannot indicate if the observed Willow Flycatchers will generate a productive population, the arrival of colonists is promising (Schofield et al., 2018).

References

BirdLife International. (2020, October 15). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Empidonax traillii. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22699848/138005562

Brazil, E., & Martina, L. S. (n.d.). Empidonax traillii (willow flycatcher). Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Empidonax_traillii/

Brodhead, K. M., Stoleson, S. H., & Finch, D. M. (2007). Southwestern willow flycatchers (Empidonax traillii extimus) in a grazed landscape: Factors influencing brood parasitism. The Auk, 124(4), 1213–1228. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/124.4.1213

Kroodsma, D. E. (1984). Songs of the alder flycatcher (Empidonax Alnorum) and willow flycatcher (Empidonax traillii) are innate. The Auk, 101(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/101.1.13

Kus, B. E., Howell, S. L., & Wood, D. A. (2017). Female-biased sex ratio, polygyny, and persistence in the endangered southwestern willow flycatcher (empidonax traillii extimus). The Condor, 119(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1650/condor-16-119.1

Muller, K. L., Stamps, J. A., Krishnan, V. V., & Willits, N. H. (1997). The effects of conspecific attraction and habitat quality on habitat selection in territorial birds (troglodytes aedon). The American Naturalist, 150(5), 650–661. https://doi.org/10.1086/286087

Novitch, N. R., Westberg, M., & Zink, R. M. (2015). Migration of alder flycatchers (empidonax alnorum) and willow flycatchers (empidonax traillii) through the Tuxtla Mountains, Veracruz, Mexico, and the identification of migrant flycatchers in collections. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 127(1), 142–145. https://doi.org/10.1676/13-222.1

Schofield, L. N., Loffland, H. L., Siegel, R. B., Stermer, C. J., & Mathewson, H. A. (2018). Using conspecific broadcast for willow flycatcher restoration. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ace-01216-130123

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (U.S. National Park Service). (n.d.). National Park Service. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/southwestern-willow-flycatcher.htm

Ward, M., & Schlossberg, S. (2004). Conspecific attraction and the conservation of territorial songbirds. Conservation Biology, 18(2), 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00494.x

Willow Flycatcher. (2019, August 29). Audubon. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/willow-flycatcher

Willow Flycatcher. (n.d.). BirdWeb. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/willow_flycatcher

Willow Flycatcher Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). All About Birds. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Willow_Flycatcher/overview

Very informative, a lot of interesting information in this article. I was not previously aware of this bird.

The nests are 2-5 feet off the ground and cowbirds are a problem. It would seem that other predators such as wandering house cats would threaten the nests and the mother. Since the birds are obviously capable of flight , one wonders why the nests are not more inaccessible.

I am happy to hear that this blog informed you of the wonders of the Willow Flycatcher. Most Willow Flycatchers nest only a few feet above the ground because their preferred breeding habitat is full of dense willow thickets and other deciduous shrubs. However, cats are definitely a concern not only for the Willow Flycatcher but rather all birds! Unfortunately, domestic cats are the number one direct killer of birds. It is estimated that cat kills upwards of two billion birds a year. If you are interested, this article written by the American Bird Conservancy provides more detail on this issue: https://abcbirds.org/news/outdoor-cats-single-greatest-source-of-human-caused-mortality-for-birds-and-mammals-says-new-study/

Very interesting article. Our birding group go out weekly to various local areas in search of various birds. And each spring we usually find a Willow Flycatcher perched atop one of the trees in a fairly open meadow area. And yes, it’s the “fitz-bew” that catches our attention first.

Hi Rhonda! That’s great how you get out weekly for birding and how you get to spot some flycatchers. Happy birding!

Lots of good information in this article. Songs and calls are often the only way to identify the flycatchers. There are several flycatchers in the Oceanside area and identifying them often leads to a good debate until you hear their song.

I have yet to catch a glimpse of the Willow Flycatcher myself, but I look forward to the challenge of identifying them this upcoming spring! Thanks for reading!

Absolutely amazing and so much information, the details you have provided will help in recognizing the Willow Flycatcher next May/June

Thank you so much

That’s great to hear! Willow Flycatchers are definitely a challenge to spot with the eye alone. Hopefully, the pneumonic “fitz-bew” helps!

Great article. Very interesting to read how reintroduction via bird call recordings can make a difference.

I am glad you enjoyed it! Conspecific queues, including the song broadcasts used in this study, are being applied in many bird species’ research. It is an exciting field of study!

This is a really neat blog, Rachel! I enjoyed the photos of the WIFL enjoying the insects; It made me chuckle to myself. It was interesting to read about the cowbirds and brood parasitism as we just learnt about this in lecture. I appreciate the connection as it’s fun to link lecture material with these blogs.

Thanks, Ruby! The Brown-headed cowbird is undoubtedly a sneaky species, but its tactics are fascinating. In the future, we can hopefully spot one while birding!