Introduction:

On the forest floor, tall Douglas fir trees around you stretch their arms to the sky. Sunlight dances through the canopy onto the forest floor, illuminating the green leaves surrounding your home. Life down on the ground ain’t so bad. Heck, life as a rabbit ain’t so bad. While birds sing in the tree tops, a fresh breeze swirls across your back. Nature’s silence. A few moments later you hear a crash. As you turn to see what’s caused the commotion you’re faced with this. Eyes locked onto you like a missile, silent wing beats allowed this predator to show up right behind you. It may be half your size but it’s faster than you. You try to turn and run. Within a moment you’ve been ambushed and trapped beneath the claws of a Northern Goshawk without a hope of escaping. These are the tales of the forest ghost’s victims.

Description:

The Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) is a stout, stealthy hunter and a powerful predator (Aubudon, 2020). It’s species name comes from the latin word gentilis meaning “of or belonging to the same family” (Wordsense.eu). They are the largest of the group, you guessed it, the accipiter hawks, also known as the true hawks. Related to their locally known smaller cousins the cooper’s and sharp-shinned hawks, the Goshawks are much more inconspicuous. They are the largest in the family Accipitridae. Out of the 50 species in the family, the sizes range from the thrush sized sparrowhawk of Africa, up to a Goshawk, which is the same size as a red-tailed hawk (Britannica, 2019). The species is reverse dimorphic meaning the females are larger than the males. Ranging from 53-64 cm tall, 0.6-1.4 kg heavy and a wingspan up to 117 cm (All about birds). They are agile hunters using the element of surprise and speed to their advantage.

Identification:

Adult Northern Goshawks have a dark grey back with light grey and white barred underparts (Fig 2). Above their menacing orange to red eyes lies a white stripe (Sibley, 2016). Juveniles are more likely to be confused with other smaller accipiter hawks, like the eurasian sparrowhawk (which only occur in Europe and Asia) and the cooper’s hawk, but the larger and broader-winged Goshawk makes a bold statement with their white eyebrows and streaking on the underparts (Fig 3)(ebird). There are 9 subspecies throughout the world, each varying slightly in head colour and amount of white and barring on underparts (Ferguson-Lees et al. 2001). Accipiter gentilis laingi is the subspecies that occurs in B.C. with lighter barring on their chest compared to the European and Asian populations and a more rufus overall hue (All about birds). Northern Goshawks are relatively quiet, they have an alarm call and make a “kak-kak-kak-kak” sound when disturbed or chasing prey (Audio below) (Aubudon, 2020). They are fiercely protective of their nest and will let you or other animals know when they’ve gotten too close (All about birds).

Photo credit: Picfair (no name attached).

Photo credit: All about birds – Alvan Buckley.

Distribution and Habitat:

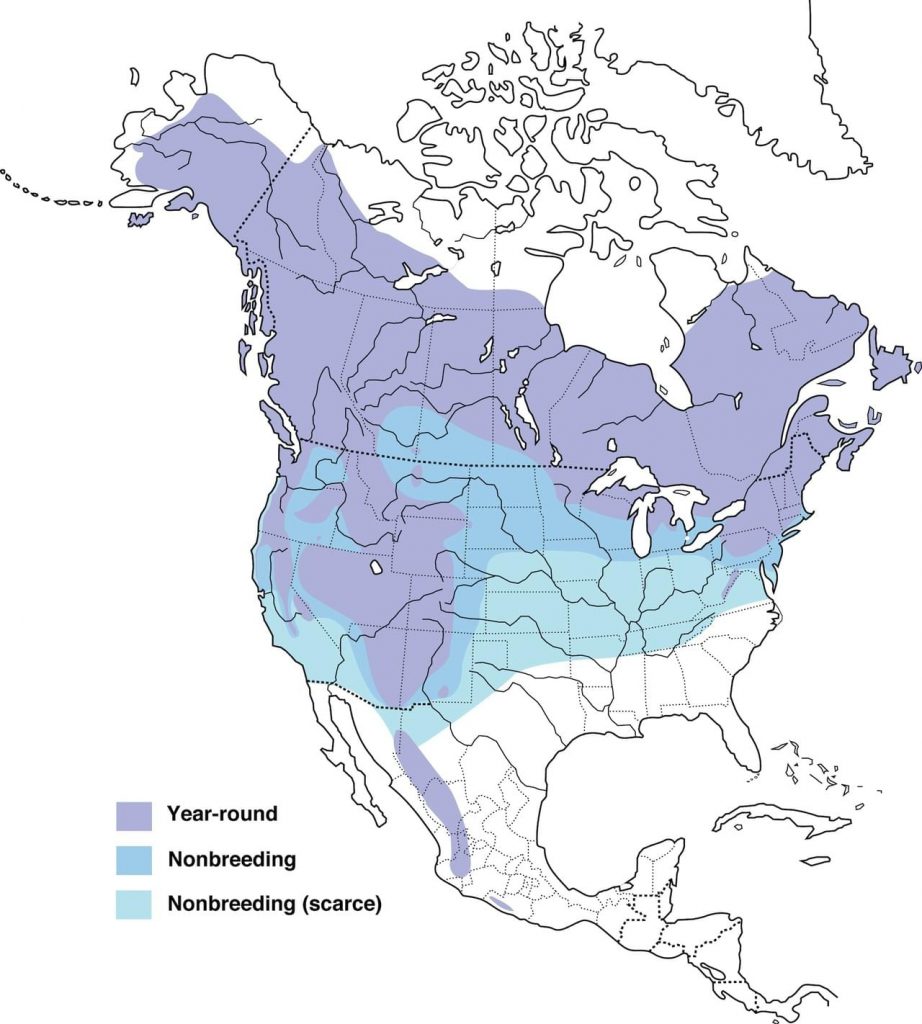

These majestic birds are found in the northern hemisphere throughout North America, Europe and Asia (Ferguson-Lees et al. 2001). In North America, they range as far south as the inland tropics of Mexico, as far north as the chilly western tip of Alaska and in every single province in Canada (Fig 4) (All about birds). Dense forest habitats are where these predators shine. Preferring mature coniferous or mixed forests, away from suburban areas (ebird). Notice the longer tail common in forest hawks, which is used to help brake and maneuver quickly at high speeds (Fig 3). The Northern Goshawks seek large trees within an area to nest. The nest is built near the trunk on a horizontal branch (All about birds). Females build the nest first out of sticks and then line the interior with softer bark and greenery (All about birds).

Behaviour:

They are a sprinter. They locate prey by watching from a perch above before navigating through the thick vegetation for their kill (Audubon, 2020). Goshawks are watchful predators, awaiting for prey to become visible in the forest canopy or ground below. They fly between elevated perches for an aerial view of potential meals below, striking swiftly with speed when an opportunity arises. They sometimes will stalk prey on foot or flying low with a watchful eye along the forest edges. They have a wide palate for birds, mammals, reptiles, insects and will sometimes scavenge pre-existing kills (Audubon, 2020). Grouse, woodpeckers, corvids, squirrels and rabbits are typical meals for these well versed birds. During courtship, Goshawks perform a sky dance which involves high circling and slow flapping, ending in a dive towards the tree tops (Hawk Mountain). Aerial displays include tucking in the tail feathers accompanied by the spreading and retracting of under-coverts called ‘tail flagging’ (Ferguson-Lees et al. 2001). Breeding pairs may mate for life and sometimes use the same nest between years, however it is more common for the female to make a new nest (Audubon, 2020). These birds are fairly sedentary, if they are going to disperse it happens in the summer months, especially for those living in higher altitudes (Ferguson-Lees et al. 2001). Typically the northern populations are more migratory and the southern populations more sedentary (Hawk Mountain).

Conservation Status:

In 2013, COSEWIC re-examined and confirmed the listing in 2000 of the Northern Goshawk subspecies A. g. laingi as a threatened population (COSEWIC, 2013). Genetic studies further discussed below have proven the A. g. laingi subspecies to be much more genetically distinct compared to the rest of the Northern Goshawks found in North America (Fig 5)(Geraldes et al. 2019). Over half of the habitat and range for this subspecies is in British Columbia with our mature coniferous forests which are in decline due to forestry and shorter harvest times. The Haida Gwaii population is at risk from introduced deer populations that are over-grazing the forest understory resulting in a decline of prey species (COSEWIC, 2013). Approximately 35-36% of nesting and foraging habitat for the Northern Goshawks are protected in Canada (COSEWIC, 2013).

Photo credits: NWPS

Interesting Tidbits:

- Goshawks have been used extensively in falconry. They were, in a lot of cases, the first birds to be used in falconry for multiple countries (Woodruff, 2020). Goshawks are extremely consistent and reliable hunters which makes them widely used for capturing food (Woodruff, 2020). A study conducted in Britain from 1970-1978 tracked the fate of 216 Goshawks imported from Finland for falconry use. They contacted owners biennially to track the fate of these animals and causes of death finding a death rate of 22% per year (Kenward et al. 1981). They are difficult animals to care for because of their fragility and not recommended as a first bird for new falconers (Woodruff, 2020).

- The Northern Goshawk was on the helmet of Attila the Hun as it represents a symbol of strength (Hawk Mountain).

- Personal hygiene is of utmost importance as they need to bathe on the daily (Woodruff, 2020).

- It used to be referred to as “the cook’s hawk” because of it feeds on grouse, ducks, rabbits, and hares (Hawk Mountain).

- About half of all Siberian Goshawks are nearly all white to blend in with the snowy terrain (Fig 6 & 7) (All about birds).

Photo credit: Conrad Tan

Photo credit: Cindy Fry

Areas of Research:

Much of the research about Northern Goshawks is about determining the subspecies ranges and differentiating between the populations around the globe. Lots of genetic work helps scientists determine the needs of each population for better management and conservation efforts.

There has been a spotlight on the Haida Gwaii Accipiter gentilis laingi subspecies, even making the CBC news. The population has been isolated on the Queen Charlotte islands for 20,000 years as they do not make migrations over large bodies of water (Alam 2019). The study conducted by Geraldes et al. last year (2019) took samples from 433 Northern Goshawks, as well as european subspecies A. g. gentilis, cooper’s hawk, sharp-shinned hawk, red-tailed hawk and a bald eagle to compare various gene loci. They used tissue samples from museum specimens, fallen feathers beneath nests, and blood samples from live specimens. The Haida Gwaii population was proven to be very distinct between the rest of North American and even other British Columbian Goshawks. This indicates the need for more specific conservation efforts towards the isolated population (Geraldes et al. 2019). Similar studies in Japan have compared their Honshu and Hokkaido populations of Northern Goshawks, which are also classified as vulnerable species, to determine the genetic diversity and status of these raptors. At the time of the study there was no concern yet in regard to a large genetic distinction requiring special conservation between the two. There is concern around imported Goshawks genetically polluting the native populations keeping them on biologists’ watch list (Takaki et al. 2009).

In the United States, studies on the home ranges of these birds was conducted by Moser & Garton in 2019. They radio-tagged 17 Goshawks from 17 different breeding locations in northern Idaho to compare their breeding ranges. Males had a mean range of 5,146 ha, 33% larger than the range of females at 3,859 ha (Moser & Garton, 2019). They concluded a larger breeding range in the north compared to Goshawks in the southwestern states. Males in Arizona had an average home range of 1,758 ha (Bright‐Smith & Mannan 1994). There are two other studies that confirm smaller home ranges in the southern states.

One last mentionable paper is on the genetic confirmation of a Northern Goshawk and cooper’s hawk hybrid. This was a wild hybrid between the two accipiter species caught at Cape May, off of New Jersey (Haughey et al. 2019). This is the first documented wild hybrid between the two accipiter species. There have been successful captive bred hybrids in the past which are often used in falconry deeming it possible but never any evidence of this happening outside of human control (Haughey et al. 2019). Hybridization between species can increase genetic diversity, be precursors to new species or traits (Grant & Grant 1992). Being the first example it may be difficult to tell what this means for either population, but nonetheless an interesting find!

Literature Cited:

Alam, H. (2019) Haida Gwaii home to a distinct but vulnerable pocket of northern goshawks. The Canadian Press. (Accessed November 12, 2020) https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/haida-gwaii-home-to-a-distinct-but-vulnerable-pocket-of-northern-goshawks-1.4986017

Audubon Field Guide. (2020) Guide to North American Birds: Northern Goshawk. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/northern-goshawk

Bright‐Smith, D. J, and R. W. Mannan (1994) Habitat use by breeding male northern goshawks in northern Arizona. Studies in Avian Biology 16:58–65.

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Northern Goshawk Accipiter gentilis laingi in Canada (2013) Environment Canada (Accessed November 9, 2020) https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_autour_palombes_northern_goshawk_1213_e.pdf

eBird (n.d.) The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (Accessed November 9, 2020) https://ebird.org/species/norgos

Ferguson-Lees, J., Christie, D. A., Franklin, K., Mead, D., Burton, P. J. K., & ProQuest (Firm). (2001). Raptors of the world. London: Christopher Helm.

Geraldes, A, Askelson, KK, Nikelski, E, et al. Population genomic analyses reveal a highly differentiated and endangered genetic cluster of northern goshawks (Accipiter gentilis laingi) in Haida Gwaii. Evol Appl. 2019; 12: 757– 772. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12754

Grant, P., & Grant, B. (1992). Hybridization of Bird Species. Science,256(5054), 193-197. Retrieved November 13, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2876983

Haughey, C. L., Nelson, A., Napier, P., Rosenfield, R. N., Sonsthagen, S. A., & Talbot, S. L. (2019). Genetic confirmation of a natural hybrid between a northern goshawk (accipiter gentilis) and a cooper’s hawk (A. cooperii): A journal of ornithology. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 131(4), 838-844. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.viu.ca/docview/2350469050?accountid=12246

Hawk Mountain (n.d.) Northern Goshawks are revered in many cultures as a symbol of strength. (Accessed: November 9, 2020) https://www.hawkmountain.org/raptors/northern-goshawk

Kenward, R., Marquiss, M., & Newton, I. (1981). What Happens to Goshawks Trained for Falconry. The Journal of Wildlife Management,45(3), 802-806. doi:10.2307/3808727

Moser, B.W. and Garton, E.O. (2019), Northern goshawk space use and resource selection. Jour. Wild. Mgmt., 83: 705-713. https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1002/jwmg.21624

Sibley, D.A. 2016. Sibley Birds West: Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, New York. pg 99.

Takaki, Y., Kawahara, T., Kitamura, H. et al. Genetic diversity and genetic structure of Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) populations in eastern Japan and Central Asia. Conserv Genet 10, 269–279 (2009). https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1007/s10592-008-9567-4

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.) All About Birds: Northern Goshawk. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Goshawk/overview

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. June 14, 2019. Accipiter. Encyclopaedia Britannica (November 10, 2020) https://www.britannica.com/animal/accipiter

Woodruff, B. (Director). (2020, March 15). Falconry: Introduction to goshawks [Video file]. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5SOwgirewc

Word sense.eu (n.d.) “gentilis” in WordSense.eu Online Dictionary (Accessed: November 10, 2020) https://www.wordsense.eu/gentilis/

Really interesting blog Kirsten, it was really awesome to learn about these impressive birds!

Your introduction was super creative and engaging, and despite the stunning imagery at the start, I’d have to say I am a little bit grateful not to be a rabbit.

I especially loved the youtube video you found since it showed just how precise Northern Goshawks are in their day to day life as they navigate through thick bushes to find prey, and at such high speeds! You mentioned that the A. g. laingi is listed as a threatened population, do you know if there’s any conservation efforts besides the protection of 35-36% of their nesting and foraging habitats targeted specifically at this genetically distinct subspecies?

The research you included was also very intriguing; it was super interesting to hear about the genetic diversity that can exist even between these different subspecies. Did you come across any evidence of genetic pollution from imported goshawks here in our local populations?

Thanks for teaching me a lot more about Northern Goshawks, I really enjoyed reading!

Maddy

Thank you for reading and for the questions Maddy! I got to do a little more in depth research so that I can answer your questions accurately and here is what I found:

(Sorry it’s a bit of a mouthfull)

Their main threat is commercial harvesting which reduces and fragments mature forest sites used for nesting and foraging. Management of the old growth forest areas and allowing for longer harvesting cycles so that second growth can mature past 80 years, eventually becoming old growth, are both needed strategies. There are Old Growth Management Areas throughout Haida Gwaii and the rest of B.C. They also have a Strategic Land Use Agreements under the BC Land Act on Haida Gwaii. This is an ecosystem based management strategy which zones for conservation of special value areas. Rate of harvest is regulated through the “allowable annual cut” which is projected for a steady state of forest age-classes, maintaining a consistent amount of old/mature areas long term.

They have also associated an indirect threat to the population with a few introduced species such as the deer, black rat, Norway rat, and red squirrel which reduce bird prey. They tried introducing raccoons as a prey species for the goshawks and it backfired. It is also a predator of the goshawk prey and likely preys on goshawk nestlings. The red squirrels are the only one in the list that the goshawks will actually hunt. Haida Gwaii implemented a ground based eradication of Norway rats with success, they’ve noticed seabird numbers increase since. The rats were feeding on eggs of black oyster catchers. The deer are up for discussion and they are working on assessing methods for deer removal or control.

Lastly, they’ve been trying to learn as much as they can about the range and population size doing telemetry work. They annually go out and record nest sites as it is illegal to harvest or clear trees around them.

There’s some research but definitely requires more to better understand. There is some range overlap between Accipiter gentilis laingi on Vancouver Island and the subspecies Accipiter gentilis atricapillus and resulting in some genetic affinities for the other. However, it appears subspecies interact through a metapopulation framework, acting as their own populations and unlikely to interbreed. They’ve found that the Haida Gwaii population is the most aligned with one another compared to other subspecies genes.

Here are the websites I got the conservation information from:

https://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/Rs-NthnGoshawkAutourPalombes-v01-2018Dec-Eng.pdf

https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/species-risk-registry/virtual_sara/files/plans/Ap-GwaiiHaanas-v00-2016Jul4-Eng.pdf

https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_autour_palombes_northern_goshawk_1213_e.pdf

Hey Kirsten!

This was a super interesting read! Like Maddy mentioned above, the video you included was sick. Man are they ever sexy birds… I desperately want to see one!

I really love the regal snow look of the Siberian Northern Goshawks. Did you come across any research on those guys in particular? I’m curious if they have a greater parasite load. I feel like I’ve heard that leucistic birds are more susceptible to parasites, and while this subspecies isn’t leucistic specifically maybe something similar happens? Or maybe the cold/snow weather limits this? I have no idea, just curious!

Thanks for a lovely, well written read!

Cheers,

Sam

Thanks Sam! I know me too!! They’re such awesome birds.

The Siberian Northern Goshawks are beauties. I tried to find some research about the Siberian subspecies specifically and their encounters with parasites and couldn’t find much. The closest I got was finding a catalogue of ascaridoid nematode parasites found in Chinese vertebrates. They listed a few that tend to occur in the stomach and intestines of Northern Goshawks but it’s not specific to a subspecies. The reoccurring genus’ were contracaecum and porrocaecum. They did find occurrences in Russia though so I’m sure there must be some that have made their way to the Siberian NOGO’s. The subspecies Accipiter gentilis albidus occur in a range of the lighter morph with some being greyer. Another study I found looked at blood parasites in Northern Goshawks, emphasizing on Leucocytozoon, but it showed low host specificity. It also had specimens from Russia but again wasn’t specific.

It would be super interesting to find out more and if I come across anything else I will let you know! But I’m sure if a chilly parasite came across a fluffy warm haven, they wouldn’t second guess hitching a ride.

Thanks so much,

Kirsten

Hi Kirsten!

Very well-written and informative blog! I really liked the tidbit section, especially the information about how they were used in falconry. I can’t even imagine trying to get one of these guys to cooperate.

I can see from the range map that Northern goshawks are year-round residents in most of Canada, and you said that 35-36% of nesting and foraging habitats for these guys are protected in Canada, so I am just wondering where those protected areas are? I think in your response to Maddy you said they were making conservation efforts on Haida Gwaii for that specific subspecies, so are there more protected areas where these guys hang out in the rest of Canada?

Thanks!

Haley

Thank you for reading it Haley! It would feel pretty powerful if you could!

Yeah, a lot of protected areas are the Old Growth protected areas and both provincial and national parks. A lot of different species benefit from the same habitat that the Northern Goshawks do, for examples ungulate winter ranges overlap as they’re also characterized by mature forest. Protected habitat for the Accipiter gentilis laingi subspecies, other than parts of Haida Gwaii, are scattered. This subspecies only occurs in the Pacific Northwest from Alaska down to Washington and all along our BC coast. This is a link to a map of protected old growth of BC: https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/563/2019/10/protected-not-protected.jpg . Most of coastal protected mature forests is the ideal habitat for these birds. It is scattered along the coastline of inlets the length of BC, however these also happen to be great sources for logging.

Combining the old growth map with this one kind of gives an idea of the extent. This is a map from the provincial government of protected areas, not necessarily old growth: http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/soe/indicators/land/print_ver/EnvReportBC_Protected_Lands_Waters_2016-06.pdf

The full list of the protected areas for the Northern Goshawk from COSEWIC includes: National Parks, Provincial Parks, Ecological Reserves, Protected Areas, Regional Parks, Conservancies, Forest Recreation Sites, Heritage Sites, Class 1 Grizzly Bear habitat, Wildlife Habitat Areas, Wildlands, Biodiversity, Mining and Tourism Areas, Old Growth Management Areas (legal and non-legal), Forest Reserves, Recreation Areas, Ungulate Winter Ranges, Strategic Landscape Reserve Design Reserves, Land Use Objective Order Schedule 9, and Wildlife Management Areas.

Hope this makes sense, thanks!

Kirsten

Hi Kirsten! This was super cool to read about, I could tell you were really into this!

Quick question regarding the tagged males vs the females. Was there a particular reason that the males had a 33% larger range than the females?

Sorry if you mentioned it and it just went over my head

Thanks for the wonderful read!

~Erika

Thank you, Erika!

The more I learned the more interested I got in them, and eventually went down the falconry rabbit hole! Males have larger home ranges during breeding as they do most of the foraging and the females stay near the nest. They also found males and females had differing preferred habitat during non-breeding. Males and females selected different habitat compositions and configurations. For example, females preferred areas with fewer, smaller openings and greater edge density and males preferred areas with smaller proportions and patches of moderately closed forests, and greater edge associated with openings. The study also found that females who were unsuccessful in their breeding had almost a 3 times larger range than those who had a successful clutch.

Thanks so much!

Kirsten