The beautiful and eerie call of a pacific loon (Gavia pacifica) can be heard across dark, and deep freshwater lakes in the summer in the Northern regions of Canada, associating the call with the sign of great Canadian Wilderness. Humans living in these regions have been enamoured by their ghostly call for centuries..

Identification

The Pacific loon is in the order Gaviiformes which is an order of aquatic birds containing only the 5 species of loon. It was formerly considered a sub-species of the Arctic Loon (Gavia arctica) but now is its own species (Birdweb.org).

The Pacific Loon is the most abundant loon species in North America (Smithsonian National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute). It is a sleek, heavy-bodied bird with a thick neck and a long pointed bill. Their wings are long and pointed, with feet set at the far back of the body.

Pacific loons are smaller than geese but larger than ravens. They are smaller than the more known Common Loon (Gavia immer), but larger than the Red-Throated Loon (Gavia stellata).

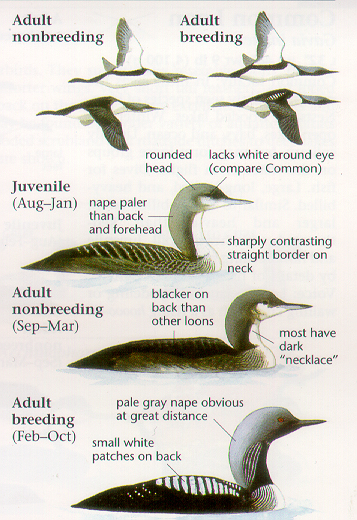

Breeding adults

Breeding adults have dusty grey heads with intricate white patches on the back.Their necks are black with crisp white lines running up it, and have a white spotted chinstrap and a white underside. Their bills and legs are very dark. Like their other loon counterparts they have a striking red eye.

Non-breeding adults

Non-breeding adults are a dark grey/brown with little white on their backs. They have a lighter underside that reaches up underneath their necks to their bill, often having a darker chinstrap or necklace.

Loons species have 4 distinct calls they make while breeding in the spring and summer. On their overwintering ground on the Pacific Coast however, loons are pretty quiet birds (Nature Canada, 2015). The most famous of their calls being the wail. The other calls are the tremolo, yodel, and hoot. They differ slightly from the more known Common Loon (Gavia immer), but see if any of them sound familiar to you!

Wail: a call given to locate other individuals, like the game ‘Marco Polo’.

Tremolo: a call given when alarmed or to announce their presence at the breeding ground.

Yodel: a territorial call made by the male to say “Hey! this is my turf!”

Hoot: Short calls given to keep contact with each other, for example a between a parent and chick, kind of like a loving hello.

Key features to identify loons in the field:

- Look for a large diving bird, when floating the body will ride low in the water

- The bill is large (usually fully dark), and will be straight at the tip

- In flight, the top of the wings will be dark, while the underside will be white and grey

- Chest and belly will be white

- In adult birds, there will be a dark chinstrap

- For breeding adults look specifically for they dusty grey nape, and the white patches on the back.

Cultural Significance

Keeping in mind that we live and learn on the lands of Canadian indigenous groups, let’s look into some of the Indigenous significance of the loon to the Coastal First Nations people, specifically here at VIU being The Snuneymuxw and the First Nations people all over Canada who have walked the same ground as the loon for thousands of years.

“Native scholar Greg Cajete has written that in indigenous ways of knowing, we understand a thing only when we understand it with all four aspects of our being: mind, body, emotion, and spirit.”

From Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants

Animals with unique vocal talents are held in high regard by Northwest Coast Peoples, who traditionally perceive words, voice and song as carriers of power and magic (First-Nations.info). The loon is thought of to have a generous and giving nature, and to hold the knowledge of other realms.

In Indigenous culture a totem is a spirit, being, or scared object that can be shared by a tribe, clan, family, or by an individual (Legends of America, 2021). The iconography of the loon in Canadian Indigenous art represents hopes and dreams. The significance to an individual with a loon totem indicates that the individual has powerful dreams, and imagination. The loon helps those individuals see the truth, and decipher what is real from their dreams or imaginations (First-Nations.info). It can also show itself to remind you that hopes and wishes can become reality.

It is reported in some cases that loons were hunted among many Northern and Coastal Indigenous people and their eggs were foraged for. Pacific Loons were specifically hunted by the Arctic, Northern Alaskan, and Ontario First Nations, including a handful of others. Skins were also used for cultural ceremonies and to make items. In some groups however, eating loons was avoided as they held great cultural significance (kuhnlein & Humphries). It is also said that many dislike the taste of loon.

Furthermore, there are many traditional stories about the loon told from numerous First Nations groups which, if interested can be read using the link below:

Habitat, Distribution, & Feeding

In the spring and summer time, the Pacific Loon actually isn’t in the Pacific at all. Pacific Loons spend the spring and summer months in Northern Canada, some going as far east as Hudson’s Bay, and sometimes as far west as Siberia. These birds call the Pacific Coast of Canada their home for the summertime though.

During the summer these birds inhabit deep, freshwater tundra or forested lakes in Northern Canada and Alaska. They prefer lakes with small islands to nest on and little submerged vegetation (Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute). At this time they will feed on invertebrates such as mollusks, aquatic insects and some plant material.

When fall time comes, these loons will will travel from their freshwater breeding habitat to marine habitats. They fly in small groups during the daytime, resting on the open ocean along their southern trip, and can fly at speeds up to about 60 km/h (All About Birds).

During the winter, Pacific Loons spend most of their time on the open ocean and can be found in bays and estuaries along the Pacific coast. During this time of year they will feed primarily on fish. If fish populations are dense, sometimes thousands of Pacific Loons can be seen feeding together. Being the the most social of the loons, they can be seen feeding with other loons and bird species.

They forage by by diving underwater swimming around schools of small fish with their large webbed feet. Some loon species have even been spotted by divers strategically swimming around and herding schooling fish to catch their next meal.

Courtship, Breeding, & Nesting

Loons rely on teamwork when it comes to relationships, and once together may mate for life! On their nesting grounds, both sexes of the Pacific Loon will court each other in a splash-tastic display. They will dip their bills in the water and splash-dive to gain a partners attention. Together they will choose a nest site and usually build a simple nest out of mud and vegetation near the water, creating an oval shaped mound with a depression in the middle. In some cases they build floating nests, but this is rare (audubon.org). The pair is very aggressive when it comes to protecting their nesting site and their chicks.

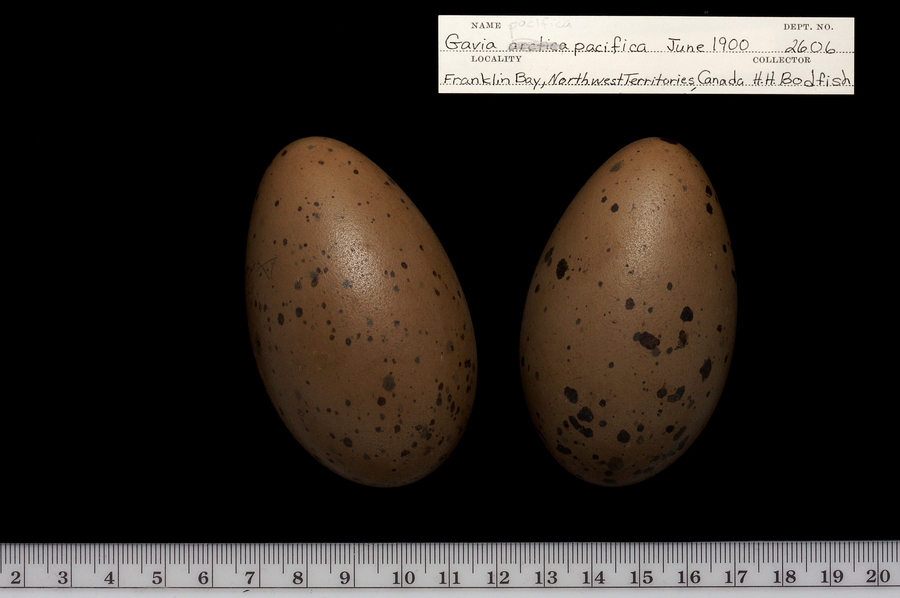

Once settled, the female will lay 1-2 eggs per breeding season. The eggs are usually brown or olive green in colour and measure approximately 3 inches long and 2 inches wide. Once again, teamwork is involved when it comes to incubating the eggs. Both the male and female Pacific Loon take turns incubating the eggs for 23-28 days (allaboutbirds.org). The newly hatched chicks can swim immediately but take some time learning how to fly. Both parents will forage for their young until it’s time to stretch out those wings, ultimately leaving the comfort of their parents’ care at about 57-64 days old (Smithsonian National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute). Sending them out into the big wide world on their way to adulthood!

Conservation

Pacific Loons are currently considered an abundant species, but could face many threats in the future as the climate changes globally. Loons are also known to be sensitive to heavy metal pollution, and face risks with increased industrial infrastructure in Northern areas. Water quality parameters like algal blooms in fresh or salt water caused by rising water temperatures and introduction of allochthonous nutrients into water systems can also be harmful to loons and many other seabirds who nest or forage in these areas (Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute).

The Audubon Guide to North American Birds has an incredible interactive map showing the predicted movement of this species in North America as temperatures rise globally in different increments:

Recent Research

There isn’t too much going on involving the Pacific loon, but there is some interesting research looking into effects that drive Pacific Loon abundance in Arctic lakes called “Effects of Fish Populations on Pacific Loon (Gavia pacifica) and Yellow-billed Loon (G. adamsii) Lake Occupancy and Chick Production in Northern Alaska” published in 2020 that combines nicely with another paper called “Occupancy of yellow-billed and pacific loons: evidence for interspecific competition and habitat mediated co-occurrence” written in 2014.

As loons are predators to many small fish species, this makes them vulnerable to prey abundance and distribution. As the waters in the Arctic warm it is predicted that hydrologic flow, water levels, and lake connectivities will change, affecting habitat selection by breeding loons (Uher-koch et. al., 2020). This team of researchers surveyed lakes in Northern Alaska to understand how changes in prey distribution and abundance would affect breeding success and populations of Pacific Loons in this area.

Pacific Loons and Yellow-billed Loons also commonly compete for resources in these northern habitats, and the Yellow-billed Loon tends to be more behaviourally dominant when it comes to their territory. Guarding it by vocalizations and dominance displays as well as physical means which can be fatal to the losing party (Haynes et. al., 2014). Research shows that Yellow-billed Loon occupancy in lakes has a very significant negative effect on Pacific loon occupancy (Haynes et. al., 2014). Limiting the Pacific Loon to smaller, shallower, and less connected lakes (Uher-koch et. al., 2020).

Arctic lake productivity is also very low, and can be drastically affected by aquatic bird abundance. This is possibly the reason why loons can be so territorial. All species that share the same breeding ground have to fight to make sure they can acquire a good nesting site and sufficient food to feed themselves and their young.

What these papers found were that Yellow-billed Loons tend to return to the same lakes year after year, while Pacific Loons have a much higher probability of colonizing new lakes, likely due to having broader habitat requirements which ultimately leads to larger population sizes of Pacific Loons (Uher-koch et. al., 2020). It was also found that the presence of certain fish species had a positive influence on Pacific Loon occupancy. The competition between Yellow-billed Loons and pacific loons (interspecies competition) however, was the biggest factor found to affect Pacific Loon populations on breeding grounds. The results regarding breeding success were varied, and not conclusive and much of the data regarding habitat changes were also inconclusive or too broad to to involved in the scope of these papers. Environmental factors leading to food web changes and population distribution can be hard to study and predict as there are a multitude of contributing variables. On the plus side though, it opens areas for new research in the field.

Another interesting project I wanted to highlight was a graduate research project by Emily Ford called “Vocalize: A Natural and Cultural History Project” which “attempts to share the Natural and Cultural History of the Loon through multiple ways of knowing” (Ford, 2016). This project is a multi-disciplinary and multi-perspective investigation that blends Indigenous knowledge and scientific study on the multifaceted scope of natural history. Emily looks at loon vocalizations and highlights that language is a form of power. Looking at the difference between English and Ojibwe definitions of language, and stressing the importance for language to be viewed through multiple perspectives. Discussing Indigenous oppression and highlighting how language can be oppressive. Here is an excerpt from one of her poems titled “Spring Wind”:

I hear Loon call

From the distant lake

Through my closed doors

Like a skipped stone

The mournful wail

taps open the still water,

once

dense

with discontent

broken by drumming over the depths now brimming

with vibrant concentric rings rippling

and a persistent pulse to shore radiating

up

through Cedar’s spine,

who sways grounded

Read more about her project here:

Interesting Facts

Loons are pretty amazing birds! Here are a few interesting facts about loons you can keep in your back pocket to pull out when the conversation runs dry at a party, if you don’t mind people thinking you’re a bit “loony“-but who cares what they think. Here’s some facts about loons.

- A group of loons are called a raft, a water-dance, a cry, or an asylum (International Bird Rescue, 2019)

- Loons have a long lifespan of about 30 years!

- A majority of birds have hollow bones to allow for easier flight mechanics, however some of the Pacific Loon’s bones are solid. This makes them less buoyant and allows for agile diving. This feature causes them to be unable to takeoff from land, needing about 30-50 metres of open water to get flying. Also causing them to have a funny gait (National Park Service, 2021).

- Modern loons have been found in the fossil record dating back to the Eocene period, about 35 million years ago. While earlier Gaviiformes ancestors date back all the way to the Cretaceous period, about 65 million years ago (Adirondack Centre for Loon Conservation).

- The Loon on the Canadian ‘loonie’ is a Common Loon, and was unveiled by the Royal Canadian Mint in Winnipeg in 1987 and was created by wildlife artist Robert-Ralph Carmichael, read more about it here.

References

Audubon. (2022, September 1). Pacific loon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/pacific-loon

First-Nations.info. (2014, September 21). The loon totem. Canada First Nations. https://www.first-nations.info/loon-totem.html

Haynes, T. B., Schmutz, J. A., Lindberg, M. S., Wright, K. G., Uher-Koch, B. D., & Rosenberger, A. E. (2014). Occupancy of yellow-billed and Pacific loons: Evidence for interspecific competition and habitat mediated Co-occurrence. Journal of Avian Biology, 45(3), 296-304. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.00394

Kuhnlein, H. V., & Humphries, M. M. (n.d.). Loons. Traditional Animal Foods of Indigenous Peoples of Northern North America. https://traditionalanimalfoods.org/birds/other-birds/page.aspx?id=6490

National Parks Service. (2021, April 30). Life Adaptations. https://www.nps.gov/gaar/learn/nature/common-loon-3.htm#:~:text=While%20most%20birds%20have%20hollow,out%20trapped%20air%20when%20diving

Naturalis Biodiversity Center. (n.d.). Pacific loon (Gavia pacifica). xeno-canto :: Sharing wildlife sounds from around the world. https://xeno-canto.org/species/Gavia-pacifica

Seattle Audubon Society. (n.d.). Pacific loon. BirdWeb. https://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/pacific_loon

Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute. (2018, August 7). Species profile: Pacific loon. https://nationalzoo.si.edu/migratory-birds/species-profile-pacific-loon

Uher-Koch, B. D., Wright, K. G., Uher-Koch, H. R., & Schmutz, J. A. (2020). Effects of fish populations on Pacific loon (Gavia pacifica) and yellow-billed loon (G. adamsii) lake occupancy and chick production in northern Alaska. ARCTIC, 73(4), 450-460. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic71533

Weiser, K., & Kaiser, K. (2021, May). Native American totem animals & their meanings. Legends of America – Traveling through American history, destinations & legends since 2003. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-totems/

Very informative blog. Great info.

Gonna be spitting facts to my boyfriend next time I go fishing and there are loons everywhere

I’ve been seeing some of the fish pictures you’ve posted! Some really nice catches!! Thank you so much for reading!

I now know more about loons than I ever thought possible! Do pacific loons have a fish species preference when it comes to food, or do they eat whatever is available whenever possible?

Hi Rebecca 🙂 They can be pretty voracious eaters especially in low productivity tundra lakes- sometimes loon species can decimate fish populations in lakes. I don’t know if Pacific Loons specifically have a preferred fish, just anything they can catch and eat (including crustaceans!). Their diet will also range from saltwater fish in the winter to freshwater fish in the summer!

Very cool. I particularly liked the addition of the loon calls and the information about the significance of the loon to our indigenous peoples.

Thank you Denman!

Loons are such amazing birds 🙂

They are pretty cool! Thank’s for reading Maja!!!

Quite possibly one of if not the most informative and awe inspiring blog I’ve ever read on the pacific loon. Not only am I star struck by the professionalism shown but the amount of effort applied has inspired and humbled me beyond measure. Very well done

Awe. Thank you! I hope you learned something new!

Very informative and engaging article! The direct examples of the loon calls bring the information to life. I also particularly liked the addition of the interesting facts. Crazy they can live up to 30 years!

Hey Emma!! Thanks for reading and thanks for your comment! 🙂 Glad you enjoyed the ‘loony’ facts!

This was so thorough and well researched! I learned a lot

Hey Des! Thank you for reading! and glad you learned something! You’ll have to do a bit of birding while you’re still in the UK lol

Absolutely amazing article. Well written, informative, and includes some interesting Loon calls!

Thank you m’am!! Hopefully if you hear one you’ll be able to say “HEY THATS A PACIFIC LOON!!!!”, everyone will think you’re a bird pro.

Great read! Very informative and intriguing

Thank you Bailey!!!

Can hardly believe these birds only live on the west coast of canada and Canada has a coin named after them.

Very interesting article, I didn’t know the pacific loon’s habitats were so far north and that they have solid bones.

Such a cool bird. Great post with lots of relevant information!

Very informative!

This is so informative I never even knew so much of that !! Such a great job well done

Really interesting blog Chloe. I never knew about the cultural significance of loons to Indigenous groups in Canada. They are very special birds.

Wow, this is the most interesting blog post I’ve read about loons! I frequent loon related blog fairly often but none have peeked my interest like this one. Extremely exhilarating to read! Keep up the good work!

Great blog Chloe, this was super informative! I recently read about how Common Loon abundence on lakes is being used as an early indicator for acid rain pollution in lakes due to how picky these loons are. Do you know if pacific loons are sensitive enough to also be used in this type of research?

Hi Sean! Thanks for your comment. I couldn’t find any research specifically on the Pacific Loon in this context, but they do share common breeding grounds and generally have the same pickiness for nesting sites (although smaller, and generally pushed out of areas where larger more aggressive loons nest and defend their territory). So I would assume they would also be able to be used in this research, but maybe to a lesser extent.