If you ever find yourself walking along the rocky terrain of Jasper National Park on a cloudy summer day, look up amongst the cliff ledges and high in the sky as you may spot the elusive Black swift. A black flash may pass your periphery as you try to catch a glimpse, but don’t look away for a moment as you will not want to miss the sight of the bird whose aerial life is shrouded in mystery.

Part I-Introduction to the Black Swift

Description and Identification

The black swift is the largest swift in North America, with adults measuring at approximately 18 cm long, flying high through the sky with tapered sickle-shaped wings and a wingspan of 38 cm (All About Birds, n.d.; Black Swift Identity, n.d.). They are one of 92 members of the family Apodidae, with all black plumage on the top of the body and grey plumage on the underside, a notched tail that often appears square, a slender body, and a white patch on either side of the forehead (All About Birds, n.d.). There is no known differentiation between the males and females, but juveniles have white speckles across their bodies as well as white edging on their flight and body feathers (All About Birds, n.d.). The bird’s long, curved, and tapered wings, as well as its aerodynamic body, allow them to fly higher than the human eye can see (Parks Canada Agency, 2021). The longevity of the Black swift is unknown, but the oldest recorded was in 2020, which was determined to be at least 17 years old via banding and recapture (Hedenström et. al., 2022). Members of the swift family can be hard to identify due to their aerial lifestyle and the similarity between species, so the first nest was only discovered in 1901 by an egg collector named A. G. Vrooman and a limited amount of research has been conducted since (All About Birds, n.d.).

Vocalizations

Black swifts are less vocal than other swifts, giving a soft yet high-pitched chattering call of twit-twit-twit-twit (Kaufman, 2014). Twits can be rapid or slow and they often call to each other during aerial chases (Marin, 1997). Have a listen to the chattering of the black swift!

The Bird that does Everything in Flight

The elusiveness of the Black swift can be attributed to spending most of their lives in the air, only coming down to nest during the breeding season. Otherwise, they eat, sleep, and mate all while airborne, reaching heights up to 12 100ft (All About Birds, n.d.). Geolocation of these birds gives evidence that they remain airborne for over 99% of the entire eight month non-breeding season, with only a few individuals making rare and brief stops (Hedenström et. al., 2022). Using still and shallow wingbeats, as opposed to the fluttery wingbeats of smaller swifts, this species can fly to extreme elevations and cover hundreds of kilometers a day (All About Birds, n.d.). As soaring birds, their wing shape and body size allow them to use the wind reflected off the ocean waves and mountain sides to lift their body high into the air (Hedenström et. al., 2022). Soaring is predominantly utilized during the day as they switch to flapping flight (continuous flapping of wings) primarily during the night hours (Hedenström et. al., 2022).

Behaviour

Black swifts are social birds, with intimate relationships and complicated interactions (Marin, 1997). When lucky, observers can see them partake in various aerial interactions including high-speed group chases where the birds will chase each other with sharp dives and erratic maneuvers (Marin, 1997). These interactions are assumed to increase the bonding of the groups and of monogamous pairs, while other aerial interactions can be aggressive (Marin, 1997). Aggressive acts can include pairs fighting using their feet as leverage, often dropping drastically in elevation and stopping themselves before reaching the canopy of the trees (All About Birds, n.d.; Marin, 1997). In addition to this, Black swifts can display terrestrial hostile behaviours such as wing-raising, where the nesting adult or older juvenile will raise their wings to intimidate the predator or opponent (Marin, 1997).

(photo by Louis-Philippe Arnhem)

Habitat

As the Black swift spends the majority of its life airborne, they prefer to forage in open areas such over bodies of water or forests, travelling great distances to do so (All About Birds, n.d.). They nest alone or in small colonies (when the terrain allows) on cliff and rock ledges that are sheltered by overhanging vegetation, cliff edges, or most commonly waterfalls (All About Birds, n.d.). Their choice of nesting location is influenced by their preference for moist nests that are dark and inaccessible to terrestrial predators (Beason et. al., 2012).

Diet

Black swifts are aerial foragers, where they use their rapid speed and high elevation to catch insects in their relatively large bill (Marin, 1997). As insectivores, they feed on flying insects including flies, flying ants, beetles, and wasps (Kaufman, 2014; Potter et. al., 2015). On days with clear skies, they will forage high above the air out of sight of the naked eye and will remain low on cloudy days (Hedenström et. al., 2022). As a predominantly aerial species, they drink water by flying low over a lake or pond and catching the water in their open bill (All About Birds, n.d.).

Breading and Nestlings

Courtship between male and female black swifts occurs through high-speed aerial chases, followed by mating while still in the air (All About Birds, n.d.). Following their courtship, it is believed that these birds are monogamous, forming long-term bonds with their partner and breeding with them in the subsequent seasons (All About Birds, n.d.). The female will produce only one brood per mating season which contains a singular white egg with a width of 1.7-2.1 cm and a length of 2.4-3.2 cm (All About Birds, n.d.). Both the male and female incubate the egg over a period of 23-30 days and the sharing of parental responsibility continues throughout the raising of their nestling (All About Birds, n.d.; Black Swift Behaviour, n.d.). The nest is comprised of mud, moss, algae, and sometimes other vegetation, which forms a small cup approximately 14 cm in diameter and 2.5 cm deep (All About Birds, n.d.). The same nest is used over many breeding seasons, with some established nest colonies frequented by Black swifts for over 20 years (Collins and Foerster, 1995).

The nestling is hatched naked with closed eyes and will remain in the nest, cared for by both parents, for 45-50 days (Black Swift Identity, n.d.). During this time, parents will take turns flying in the sky to collect insects and will return to their sole nestling to regurgitate a sticky mixture of insects and saliva (All About Birds, n.d.; Collins and Foerster, 1995).

Click here to see a video by Benjamin Clark of a Black swift incubating it’s egg!

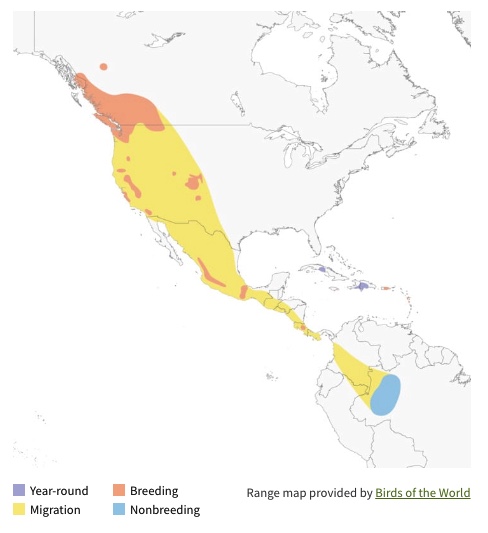

Distribution and Migration

Black swifts spend their summer breeding season (May-September) across North America, with 80% of the population in British Columbia and the rest scattered throughout southern Alberta, northwestern U.S., southwestern U.S., and Mexico (Black Swift, n.d.; Parks Canada Agency, 2021). During migration, the Black swift flies thousands of kilometers to South America and the Caribbean, with many traveling to the lowland rainforests of Brazil to spend the winter months (Beason et. al., 2012). Interestingly, it was unknown where the species spent their non-breeding season until a group of Colorado researchers used small geolocators on four birds, tracking them to Brazil where there had never been any reported sightings as they blend in with other swift species in the area (Gunn et. al., 2021).

Conservation

Despite the little information known about the black swift, it is known that their populations are declining, and action must be taken. It is estimated that approximately 50% of the population has declined since 1973, and the species was listed as endangered by Canada’s Species at Risk Act in 2019 (Parks Canada Agency, 2020). This decline in population is most likely a result of a decline in flying insects, climate change, and human activity (Parks Canada Agency, 2021). A decline in flying insects is detrimental to the insect foraging species and may be caused by a number of different factors including pesticide use, extreme weather, and the destruction of wetlands (Gunn et. al., 2021). Climate change may play a role as the shrinking of glaciers leads to a decrease in free running water such as waterfalls, limiting the number of suitable breeding habitats (Gunn et. al., 2021). In addition to this, greater habitat loss has occurred due to human activities such as intensive agriculture and deforestation (Parks Canada Agency, 2021). All these events lead to the decline in food availability and habitat, highlighting the need to protect the species. To prevent the extinction of the mysterious species, known nesting sites such as Two Valley Canyon in Jasper national park are closely monitored and closed during the breeding season, which prohibits climbers and hikers from disturbing their activities (Parks Canada Agency, 2021).

Part II- Moonlight Drives Nocturnal Vertical Flight Dynamics in Black Swifts

Lunar cycles affect many nocternal animals, with the reflection of moonlight allowing enough vision to forage throughout the night, but is the nocturnally active Black swift influenced by the changes of the moon phase? This was the question posed by Hedenström and his colleagues, who uncovered how the lunar cycle can influence the flight behaviour of the species. The research team used multisensor loggers that monitored the light, flight activity, and altitude of seven Black swifts over the course of four years (Hedenström et. al., 2022). Periodical altitude increases during dusk and dawn were identified, with the purpose of this behaviour assumed to be for reorientation, social behaviour, or for sleeping while gliding down from the high altitude (Hedenström et. al., 2022).

Futhermore, it was found that the altitude of nocturnal foraging increased with the phases of the moon ranging from low altitudes at the new moon to 2000-4000 m above sea level during the full moon (Hedenström et. al., 2022). The preffered nocturnal altitude was around 2000 m, but some individuals ascended up to 5000 m during the full moon (Hedenström et. al., 2022). Their flight patterns during this time suggested to the researchers that they were actively foraging or avoiding predators such as the bat falcon (Hedenström et. al., 2022). This indicates that their changes in maximum altitude may be related to the patterns of insects, as there is evidence that many insects also change altitude in accordance with the lunar phase (Hedenström et. al., 2022). Meanwhile, their daytime foraging behaviour and altitude remained relatively the same throughout the lunar cycle (Hedenström et. al., 2022). Interestingly, it was found that when the birds were at high altitudes during a lunar eclipse, they would promptly descend to low altitudes with the shading of the moon (Hedenström et. al., 2022). At the time of publication, the Black swift was the first bird species to have periodic altitude increases in accordance with the lunar phases (Hedenström et. al., 2022).

The research presented is a piece to solving the puzzle that is the life history of the elusive black swift. As technology advances, greater information on the behaviour of the species can be found, allowing for more effective conservation and protection of the populations and their habitats.

References

Beason, J. P., Gunn, C., Potter, K. M., Sparks, R. A., & Fox, J. W. (2012). The Northern Black Swift: Migration Path And Wintering Area Revealed. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 124(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1676/11-146.1

Black swift. (n.d.). Www.natureconservancy.ca. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://www.natureconservancy.ca/en/what-we-do/resource-centre/featured-species/birds/black-swift.html

Black Swift Behaviour – Whatbird.com. (n.d.). Identify.whatbird.com. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://identify.whatbird.com/obj/232/identification/Black_Swift.aspx#:~:text=Wingspan%20Range%3A%2038%20cm%20%2815%20in%29%20Wing%20Shape%3A

Black Swift Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Black_Swift/overview

Collins, C.T., Foerster, K.S. (1995). Nest site fidelity and adult longevity in the Black Swift (Cypseloides niger). North American Bird Bander. 20, 11–14.

Gunn, C., Hirshman, S. E., & Aagaard, K. J. (2021). Trends in Black Swift (Cypseloides niger) breeding phenology, productivity, and nest success in southwest Colorado, 1996–2017. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 132(2). https://doi.org/10.1676/1559-4491-132.2.317

Hedenström, A., Sparks, R. A., Norevik, G., Woolley, C., Levandoski, G. J., & Åkesson, S. (2022). Moonlight drives nocturnal vertical flight dynamics in black swifts. Current Biology, 32(8), 1875-1881.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.03.006

Kaufman, K. (2014, November 13). Black Swift. Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/black-swift

Marin, M. (1997). On the Behavior of the Black Swift. The Condor, 99(2), 514–519. https://doi.org/10.2307/1369958

Parks Canada Agency, G. of C. (2020, October 19). Black swifts – Banff National Park. Www.pc.gc.ca. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/banff/nature/conservation/Especes-species/martinet-swifts

Parks Canada Agency, G. of C. (2021, November 18). Black swift – Jasper National Park. Www.pc.gc.ca. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/jasper/nature/conservation/eep-sar/martinetsombre-blackswift

Potter, K. M., Gunn, C., & Beason, J. P. (2015). Prey items of the Black Swift (Cypseloides niger) in Colorado and a review of historical data. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 127(3), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1676/14-152

Wow what an amazing bird, I am blown away by how much time they spend in the air, I didnt know birds could drink water while in flight, that’s crazy! Also super interesting how their behavior is influenced by the moonlight, as Killdeer (the species I did my blog on) foraging behaviors are also influenced by lunar cycles.

Thank you for your interest in the Black Swift Codey! I also found their duration of flight very interesting. As it is such an elusive species I found a lot of conflicting information about just how long they remain in flight, but Anders Hedenström calculated that they will fly approximately the distance to the moon and back up to 7 times over the average lifetime!

Whoah I didn’t know that birds could spend so much of there time airborne I assumed they’d need to rest. Do they use wind pockets to stay up that long? Also do you think there declining numbers could be because they have such huge migration patterns and the uptick of tropical storms (probbaly linked to climate change) or are they well equipped to handle these issues?

Hi Molly! These birds utilize air columns from wind reflected upwards off of surfaces such as mountains and oceans, as well as use rising air from thermal columns to help them lift up high. It appears that tropical storms are not an issue for this species, but rather the declining insect population (also due to climate change) is the most prominent challenge they are facing.

Wow so cool! I never knew this!

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed the read.

I really enjoyed Darren Clark’s photo of their nesting areas! So cute! These birds are so interesting, I am shocked that they are in this area.

Thank you! I was also surprised since I’d never heard of them before, but the more I’ve read about how hidden they remain I’m not surprised I wasn’t the only one.

This is a great blog, Mackenzie! The current research is really interesting. I had no idea that Vaux swifts were influenced by the lunar cycles. The researchers speculated that these birds are following insects, by any chance did they mention why the insects were influenced by the lunar cycles?

Thank you Rachel! They did not mention in their research why insects were influenced by the lunar cycle, but they did cite a paper by Nowinszky et. al. that explained that many insects have a lifecycle that follows the lunar phase. If you would like to learn more the article is listed below:

Nowinszky, L., Petranyi, G., & Puskas, J. (2010). The Relationship Between Lunar Phases and the Emergence of the Adult Brood of Insects. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 8(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/0801_051062

Great read, Mackenzie! These birds are really incredible, being able to stay airborne for that much time. Is it known how large their nesting colonies can become? I imagine tracking these birds would be difficult.

Thank you Sam! It is not known how large their colonies become, but it appears they attempt to fit in as many nests as a particular space allows with some space between the nests. However, this can be tricky as their nesting sites are often quite small and can only hold a few nests.