The sun is setting as you walk through the forest, and all’s quiet except for the buzz of mosquitos and a faint beeping sound in the distance. “Is the beeping getting closer?” you ask yourself. You keep walking, and then BOOM something crashes through the trees behind you. It sounded like a race-car whooshing by, but there’s nothing there. Now that sound is above you and before you know it, the race-car is back. A dark shape hurdles towards the ground, but swerves up at the last minute and lands facing you. It is a slender brown bird and it is swaying its hips and tail. You want to walk away, but now you’re intrigued. It puffs out its neck and starts to croak. He’s clearly mistaken you for a female of his species. You try to explain his mistake to him, but he just keeps swaying. Now you’re mesmerized by his moves and can’t look away. You have been seduced by the Common Nighthawk.

Description

The Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor) is a medium sized slender bird belonging to the family of Nightjars and Nighthawks (Caprimulgidae). This grouping of birds is commonly referred to as Goatsuckers, after the outdated false belief that they would attack and suckle goats in the night. (Sibley, 2016). The Common Nighthawk is average in size for a Goatsucker as it weighs between 65-98g, has a length between 22-24cm and has a wingspan of 53-57cm. The name Nighthawk poorly represents this bird as they’re not primarily nocturnal nor are they closely related to hawks (All About Birds). However, the Nighthawks scientific name does a far better job at representing this fascinating bird. Its genus name is a blend of two words: khoreia, meaning a dance with music, and deile, meaning evening. However, you’ll have to keep reading to fully understand why this genus name fits so well. Additionally, the species name of minor reflects its small stature (Jobling, 2010).

Identification

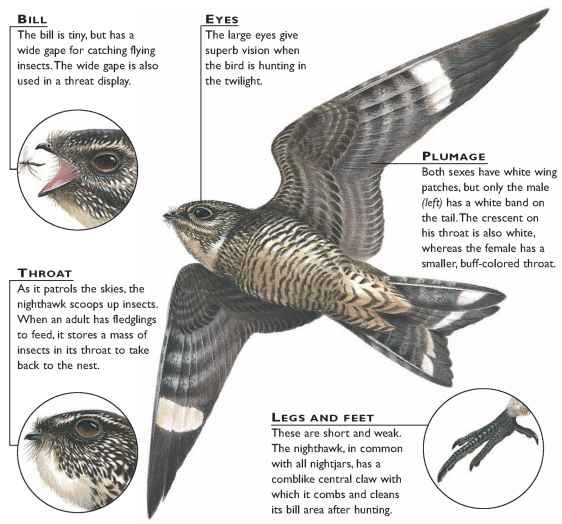

Common Nighthawk adults are characterized by a series of camouflaging grey and brown stripes which help them blend into their daytime roosts on fences and trees. Furthermore, the Common Nighthawk also has a short neck, large eyes and a short beak which exaggerate the size of the head (All About Birds). When in-flight the Nighthawk has long pointed wings which display a distinct white patch near the end of each wing. Additionally, a distinct white V-shaped marking can also be seen on the neck of the Nighthawk (eBird). The best way to distinguish between males and females of this species is to look for the white bar on the tail which is only found in males. (Landbird).

The Common Nighthawk has many distinct calls and songs, ranging from an “aug-aug” sounding call to a series of “peents and booms”. These booms come from the male Nighthawk’s wings as they dive to the ground to impress females or to startle intruders (Audubon).

Habitat and Distribution

The Common Nighthawk can be found across most of Southern Canada and as far South as Argentina. However, the southern hemispheres are predominantly occupied by non-breeding residents (All About Birds). Breeding residents can be found as far north as the Yukon and down through the continental United States. Breeding individuals tend reside in more open habitats such as prairies, forest openings, bogs and post-fire areas. These birds are not limited to the wilderness as they are also commonly seen living in the urban environment with their favourite nesting spots being gravel roof tops (Government of Canada). During migration Nighthawks utilize a variety of habitats including river valleys, marshes and woodlands (All About Birds). While little is known about their wintering habitat in South America there is some evidence that these birds prefers disturbed habitats such as farmland (Ng et al, 2018).

Behaviour

Common Nighthawks are most active at dusk and dawn but have been seen foraging in the day during storms. When they aren’t foraging for food, Nighthawks can usually be found resting on tree branches or fence posts but are always hard to spot (eBird). Nighthawks fly similarly to bats with continuous flapping and occasional glides. Their flight is so alike to that of bats that some regions have nicknamed them bullbats (Parker, 2020). These predators are strictly insectivores feeding almost exclusively on flying insects. Rural dwelling Nighthawks choose to hunt over open fields and lakes while Nighthawks residing in urban settings often hunt over brightly lit areas such as stadiums as the lights attract prey and make them easier to spot (Audubon). Nighthawks are typically lone hunters however, during migrations they can form flocks and roost in groups (All About Birds). Migration occurs in the late fall as they fly from across North America down to South America. These non-breeding birds settle down south until early April when they begin their migration back (Ng et al, 2018).

Males of the species are very territorial during breeding season and are rarely seen overlapping with one another. Males attract females by preforming incredible dives through the forest, pulling up just meters above the ground. During this display the diving motion creates a boom which can act as a mating call and a warning to other males. Once they have found an interested female the male Nighthawk will land Infront of her, displaying his tail and showing his throat patch while croaking (All About Birds). And just like that he has a girlfriend. Additionally, researchers have found that males will only display this booming display within their own exclusive nesting territory (Knight, Brigham & Bayne, 2022).

Once the two lovebirds have paired, they chose a nest site which is typically on the ground in bare soil or sometimes on raised objects such as stumps. No nest is formally constructed instead the eggs are laid on a flat surface, with egg numbers ranging from 1-3 (Audubon). The female incubates the eggs and young only leaving them to feed. Both parents care for the young, feeding them regurgitated insects and preforming diversions to draw away predators (All About Birds).

Conservation Status

The Common Nighthawk is a species in steep decline with populations decreasing by almost 50% since 1966. There are an estimated 23 million breeding pairs globally however, solid estimates of the number of Nighthawks are hard to produce. This is due to the Nighthawks excellent camouflage making them extremely hard to count (All About Birds). Common Nighthawks have been declining in the urban environment for a plethora of reasons. Firstly, increasing numbers of urban crows are consuming Nighthawk eggs and taking over their roosts (Audubon). Furthermore, Nighthawks often forage over lit roads and fall victim to collisions with cars. Lastly, due to increasing global temperatures the rooftop nesting sites of these birds are becoming excessively warm during breeding season. This is leading to increased stress among the Nighthawks and especially their chicks (Newberry & Swanson, 2018). As for the rural Nighthawks, the number one cause of their decline is linked to the decreasing number of flying insects. This decrease is caused by the implementation of pesticides which are curbing insect populations. Moreover, habitat loss is also impairing the Common Nighthawks success (All About Birds).

Interesting Facts

- Common Nighthawks have one of the longest migration routes out of any North American bird (All About Birds).

- They often show up far out of their range. They have been recorded around Greenland and Iceland, and even as far east as the British Isles (All About Birds).

- A group of Nighthawks is called a “kettle” (What Bird).

- Stomach analysis has revealed that Nighthawks can eat over 500 mosquitos in a day (What Bird).

- There are 9 Subspecies of the Common Nighthawk, including one that breeds on Vancouver Island (Birds of the World)

- There have been over 460 000 recorded observations of the Common Nighthawk on eBird.

Areas of Research

The research around the Common Nighthawk is very diverse however, the three most prominent areas of research are about their migration, habitat and on their declining numbers. So, in this section I want to highlight a paper that discusses each of these three areas.

Until recently we knew very little about the Common Nighthawk’s migrations other than they spend the winter in South America. However, at 2018 study changed this when they applied 3.5g pinpoint GPS-Argos tag on mature males. The birds were tagged in Northeastern Alberta and were found to overwinter in the Cerrado and Amazon Biomes in Brazil. In addition to this the migratory pathways of these birds were clearly identified. These birds flew over the Gulf of Mexico to Cuba and then across the Caribbean Sea and south to Brazil (Ng et al, 2018).

This study also shed light on the previously unknown non-breeding habitat of the Nighthawks. It found that the birds chose to roost in forest patches spread among open areas such as croplands, grasslands and shrub lands. Moreover, these non-breeding habitats were always far from water which contrasts their breeding habitats which have a strong association with water (Brigham et al, 2011). However, this could have just been a result of poor resolution in the remote sensing data (Ng et al, 2018).

As previously mentioned, the Common Nighthawk’s numbers are dwindling, and this study suggests yet another factor that may be contributing to this. Since the migration routes are so similar between members of this species it leads to higher interspecific competition as this is the only time in their life cycle where they overlap to this degree. Therefore, if habitat or food becomes limited along their migratory routes than many may not survive the trip. However, the data gathered from this study could help to identify vulnerable areas and bottle necks. This could then lead to the appropriate conservation strategies to be implemented effectively (Ng et al, 2018).

References

Audubon (n.d.). Guide to North American Birds: Common Nighthawk. Oct 17, 2022, from: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/common-nighthawk

Brigham, R. M., Ng, J., Poulin, R. G., & Grindal, S. D. (2011). Common nighthawk (Chordeiles minor). The birds of North America, pg. 213.

eBird (n.d.) The Cornell Lab of Ornithology Common Nighthawk. Retrieved Oct 16, 2022, from: https://ebird.org/species/comnig

Government of Canada (2018). Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor): COSEWIC assessment and status report 2018. Retrieved Oct 17, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/cosewic-assessments-status-reports/common-nighthawk-2018.html

Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm. London. Pg. 104. https://archive.org/details/Helm_Dictionary_of_Scientific_Bird_Names_by_James_A._Jobling

Knight, E. C., Brigham, R. M., & Bayne, E. M. (2022). The Big Boom Theory: The Common Nighthawk wing-boom display delineates exclusive nesting territories. The Auk, 139(1), ukab066.https://academic.oup.com/auk/article/139/1/ukab066/6408601?login=false

Landbird Species at Risk in Forested Wetlands. (n.d.) Common Nighthawk Identification. Retrieved Oct 17, 2022, from: https://landbirdsar.merseytobeatic.ca/common-nighthawk-identification/

Latta, S. C., & Latta, K. N. (2015). Do urban American Crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) contribute to population declines of the Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor)?. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 127(3), 528-533. https://meridian.allenpress.com/wjo/article-abstract/127/3/528/129912/Do-Urban-American-Crows-Corvus-brachyrhynchos

Newberry, G. N., & Swanson, D. L. (2018). Elevated temperatures are associated with stress in rooftop-nesting Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor) chicks. Conservation physiology, 6(1), coy010.https://academic.oup.com/conphys/article/6/1/coy010/4916083?login=false

Ng, J. W., Knight, E. C., Scarpignato, A. L., Harrison, A. L., Bayne, E. M., & Marra, P. P. (2018). First full annual cycle tracking of a declining aerial insectivorous bird, the Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor), identifies migration routes, nonbreeding habitat, and breeding site fidelity. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 96(8), 869-875https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/cjz-2017-0098

Parker, L. (2020). Booming Bullbats: afield with the Common Nighthawk. Retrieved Oct 18, 2022, from https://www.mainenightjar.com/post/booming-bullbats-afield-with-the-common-nighthawk

Sibley, D.A. 2016. Sibley Birds West: Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, New York. pg. 222.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.) All About Birds: Common Nighthawk. Retrieved Oct 16, 2022, from: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Nighthawk/overview

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.) Birds of the World: Common Nighthawk. Retrieved Oct 19, 2022, from: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/comnig/cur/introduction

What Bird, (n.d.). Field Guide to Birds of North America: Common Nighthawk. Retrieved Oct 19, 2022, from: https://identify.whatbird.com/obj/387/_/common_nighthawk.aspx

I’ve seen some claims that the west coast subspecies ‘may’ occasionally nest in upper sand dunes where it’s more protected but still open. Did you find anything about the west coast BC nesting habits?

Thanks for reading Kaitlyn. The Vancouver Island sub species has a strong preference to open habitat nesting, so sand dunes would absolutely be acceptable to them. In fact the largest nesting site for nighthawks in BC is in a similar habitat along the Thompson river.

Hi Sean! You mentioned some research investigating the declining numbers of the species, and I was wondering if there are any conservation efforts taking place in response to the decline?

Hey Mackenzie, thanks for commenting! There are some small efforts to better identify CONI nesting habitats for future conservation efforts however, there seem to be no current large scale efforts to protect these birds. Despite this, efforts to protect flying insects are indirectly helping nighthawks and other insectivores.

Great blog Sean! I was wondering, as you mentioned their declines can be caused by a multitude of factors including heat and insect abundance if these birds may end up breeding farther north as time goes on, as it would be colder and insect populations would be less affected by anthropogenic effects, that it may shift their breeding distribution farther north?