Now I know what you’re thinking: “No way am I really going to read a long-winded blog post about some boring seagull when there are so many other interesting bird blogs about much cooler that birds I could be reading”. But trust me this once, this is a gull unlike any that you have heard of before; and I hope by the end of reading this you will come to appreciate these handsome—and frankly, criminally underrated—birds almost as much as I do.

Classification: How did it get the name?

The Bonaparte’s gull (Chroicocephalus philadelphia) is a member of the Laridae family (gulls and terns) in the order Charadriiformes (sea and shorebirds). Its common name was given to honour, not the well-known revolutionary Napoleon, but his nephew Charles Lucien Bonaparte; who you might be surprised to learn was a renowned ornithologist who worked both in the United States and in Europe. As of 2022, he is credited by the International Ornithological Committee for coining the Latin names of more than 600 genera, species and subspecies of birds in his career. But enough about the man, lets talk birds…

Identification: How can I tell them apart from other gulls?

Bonaparte’s gull is rather small and sleek compared to a lot of other gull species, close in size to an American Crow. Their plumage is largely similar to most other gulls, with white bodies and light grey backs and wings. Where they differ from most gulls however, is the colouration of their heads.

In breeding plumage, the Bonaparte’s gull can be easily identified as they look ready to pull off an elaborate bank heist. With an all-black head with only a little white plumage left around the eyes, this colour pattern gives the appearance of a black balaclava worn to conceal their identities, but ironically giving them away. In their non-breeding plumage, these gulls lack the full black balaclava, but can still be identified by a black spot on their cheek behind the eye.

In both adult plumages, the Bonaparte’s gull can also be identified by white wedges on the front side of the wing tips, which contrast the gray colouration of the rest of the wing. Other identifying features include a narrow, all-black beak—colour matched to its black balaclava in breeding plumage—and bright red-orange legs.

Juvenile Bonaparte’s gulls display the same black spot visible in the adult non-breeding plumage but differ from adults in their mix of brown and grey colouration of the body and wings, and a black band across the end of the tail. The brown patches and black tail band are retained throughout the majority of the gull’s first year of life. Juveniles can also often be identified by black markings present across the whole length of the posterior edge of the wing, while adults only retain black markings on the distal end of the wing. During their first summer, they may begin to display some black feathers on the head, but the balaclava will not be fully formed.

Migration and Distribution: Where can I find them?

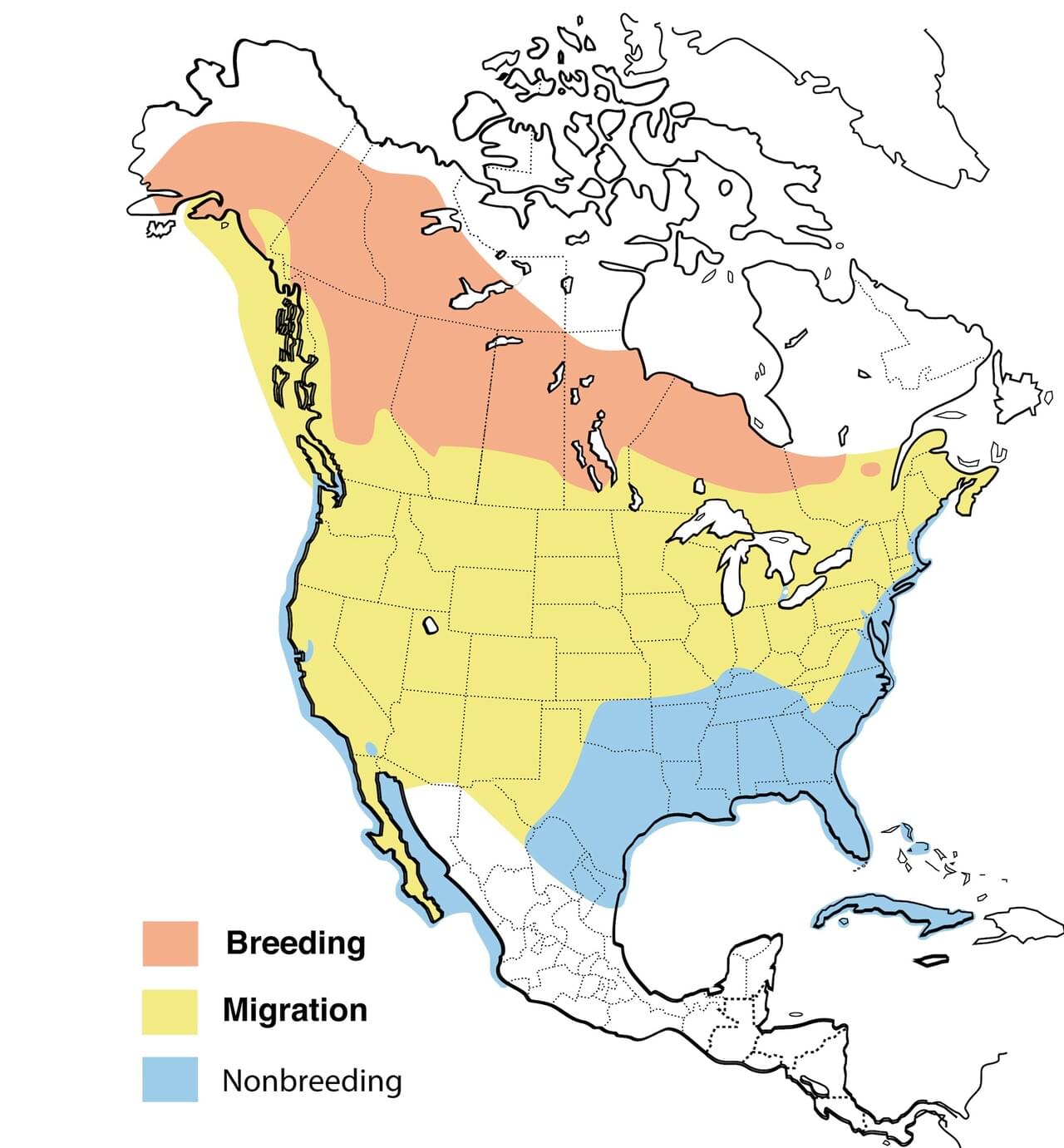

Bonaparte’s gulls are migratory birds. While they are commonly found across all of North America, their population moves north and south across the continent with the changing of the seasons. These gulls winter on the southern coasts of North America, typically beginning their flight northward around March-April (Burger, J., & Gochfeld, M., 2020). The migration routes they take are varied, but much of the population will follow river valleys, lakes, and other bodies of water. Breeding territory for the Bonaparte’s gull is also vast and dispersed but located mostly in the north-western areas of the continent. Gulls can usually be found in breeding grounds from May to early September (Burger, J., & Gochfeld, M., 2020). Some transatlantic vagrants have also been reported in western Europe and Norway (All About Birds).

Habitat and Behaviour – Summer Breeding Season

During the breeding season, Bonaparte’s gulls fly inland to the boreal forests of southern Alaska and north-western Canada. While inland, they prefer to stick around wet marshy areas, or near lakes and streams. Bonaparte’s gulls are unique among seagulls in their tendency to construct nests in trees. The nests are usually built near the trunk and can be as high as 50 feet off the ground (All About Birds). The construction of these nests is a joint effort of a breeding pair of gulls; and sometimes used over several breeding seasons. Their elevated nests compliment their feeding habits during the breeding season; which consists largely of flying insects, mostly caught on the wing or off the surface of trees and other plants (Braune, B. M., 1987).

Mate selection among Bonaparte’s gulls largely occurs in midair around the nesting grounds: courting gulls will call loudly while swooping and diving at each other in displays of ultimate gull prowess. The courtship ends with two gulls deciding they are impressed with the other’s swooping and screaming, and landing in a nearby tree, where they continue to scream at each other while bills opened upwards and heads bobbing up and down (Twomey, A. C., 1934). Sometimes they will do this for minutes at a time, before they decide that enough is enough and just sit together in silence, enjoying each others company.

Once a happy breeding pair of Bonaparte’s gulls is established, the two will collaboratively construct their nest. Breeding gulls value their privacy and personal space, and therefore tend to avoid building nests on already occupied trees; it is rare to see two nests built less than a hundred feet from each other (Twomey, A. C., 1934). The nests are constructed mostly of spruce and tamarack twigs, held together with lichen, and lined with tree bark.

Females typically lay a clutch of 2-4 eggs, which are incubated by both parents for about 3 weeks before hatching. Once hatched, the chicks stay in the nest for their first 6-7 days of life before following their parents out (Sandilands, A., 2011; Jehl Jr., J. R., 1971). From the laying of the eggs to the young leaving the nest, the parents will defend the nesting site aggressively against potential predators. They are known to scare off intruders through aerial dives accompanied by shrill calls (Burger, J., & Gochfeld, M., 2020). Due to the elevated placement of most Bonaparte’s gull nests, aerial predators like ravens and hawks pose the biggest threat. However, they have also been known to mob humans that have encroached on breeding territory (Twomey, A. C., 1934).

Habitat and Behaviour – Non-breeding Winter Season

Over the colder winter months, Bonaparte’s gulls tend to stay closer to the east and west coasts of the United States, as well as Cuba, the Gulf of Mexico, and some Caribbean islands (Latta, S. C., & Rodríguez, P. G., 2018). Their non-breeding habitats allow for a much greater diversity of feeding opportunities than their northern breeding habitats permit. Non-breeding Bonaparte’s gulls are known to feed in ponds, lakes, river marshes, bays, and oceans (Burger, J., & Gochfeld, M., 2020). Notably, they are almost never found scavenging human refuse around garbage dumps and landfills like many other gull species; they consider themselves above that.

While ocean feeding, these gulls are known to gather along tidal rips and upwellings as far as 20 km from shore. Their diet here consists mainly of small fish, crustaceans (especially shrimp and krill), and other marine invertebrates (Burger, J., 1988). One interesting feeding technique Bonaparte’s gulls use while out on open water is known as “conveyer belt feeding”, wherein large flocks of gulls fly upwind very close to the water’s surface so they may quickly dive at prey below. When they reach the end of the food patch they quickly fly upward, allowing the wind to carry them back to the start of the que where they may do it all over again, hence the name (All About Birds).

While they may consider themselves too good for garbage picking, Bonaparte’s gulls certainly don’t consider themselves above thievery. Like many gull species, they are known to steal food from other birds in lieu of doing the hunting or foraging themselves; this is often referred to as kleptoparisitism (pretty cool, see Parasitic jaeger for more on this). Smaller shorebirds such as dunlin, plovers, and yellowlegs are often victims of this behaviour, with gulls stealing hard earned earthworms right from their mouths (Payne, R. B., & Howe, H. F., 1976). Bonaparte’s gulls will also kleptoparasitize small fish from diving birds like mergansers and grebes. However, they will also more opportunistically catch fish that have been brought to surface in fleeing from these diving birds (All About Birds).

Conservation

Bonaparte’s gull is considered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List as being of least concern, meaning that the population is large enough and dispersed enough that it is not considered vulnerable. In fact, population trends for this bird are currently increasing. Essentially, the Bonaparte’s gull is not going to disappear any time soon (thank God).

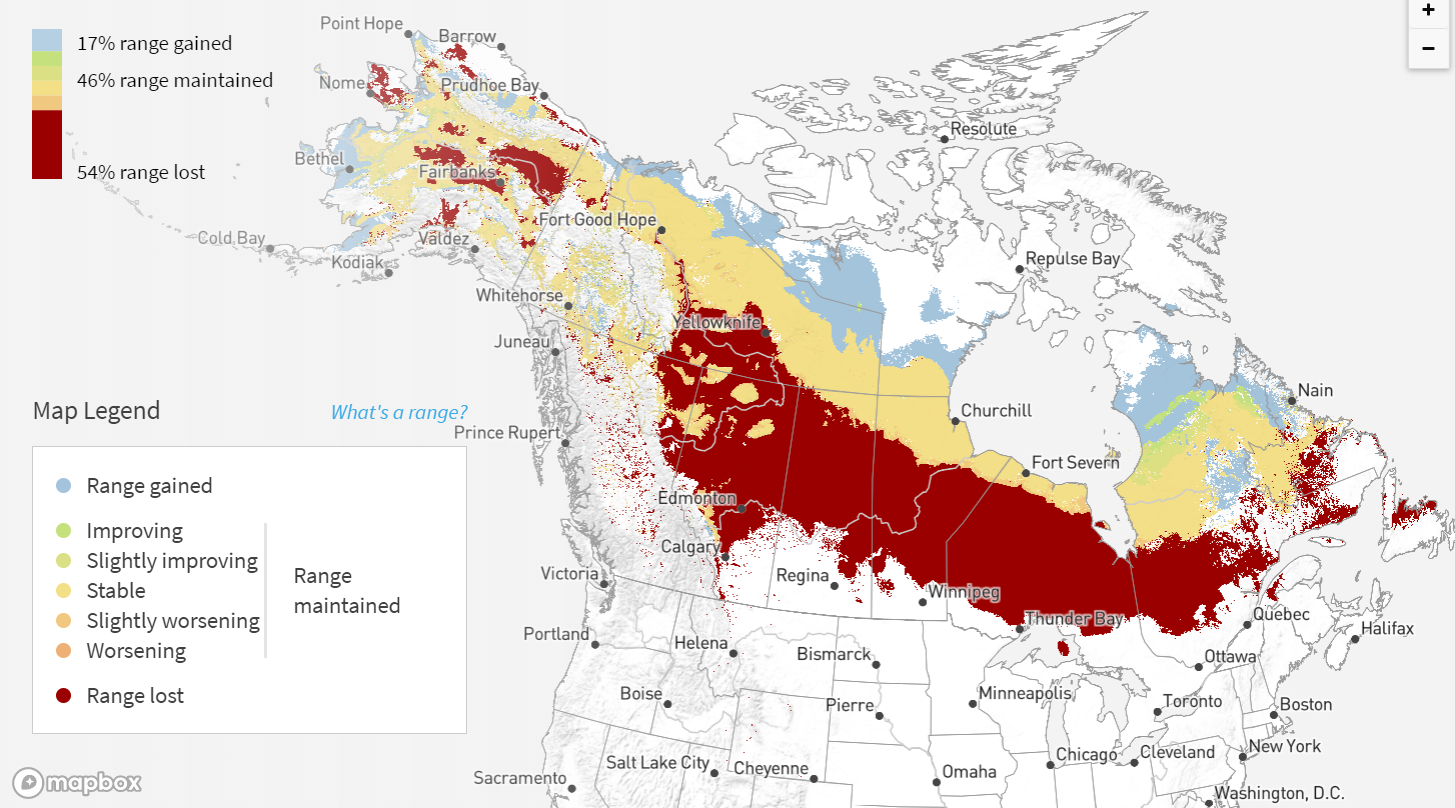

So that is all well and good. However, like most living things, the viable habitat of Bonaparte’s gulls is expected to be heavily impacted by climate change. Audubon combines sophisticated climate models with the data from millions of observation accounts to predict as high as a 54% loss of summer breeding range resulting from a 2° increase in global temperatures. For context, at current warming rates we are expected to reach this temperature by 2050.

Current Research

As briefly mentioned prior, despite the regular territory range of this gull being limited to the North American continent, several sightings have been reported of Bonaparte’s gulls in western Europe. Birds that are found far away from their normal habitat range are referred to as vagrants.

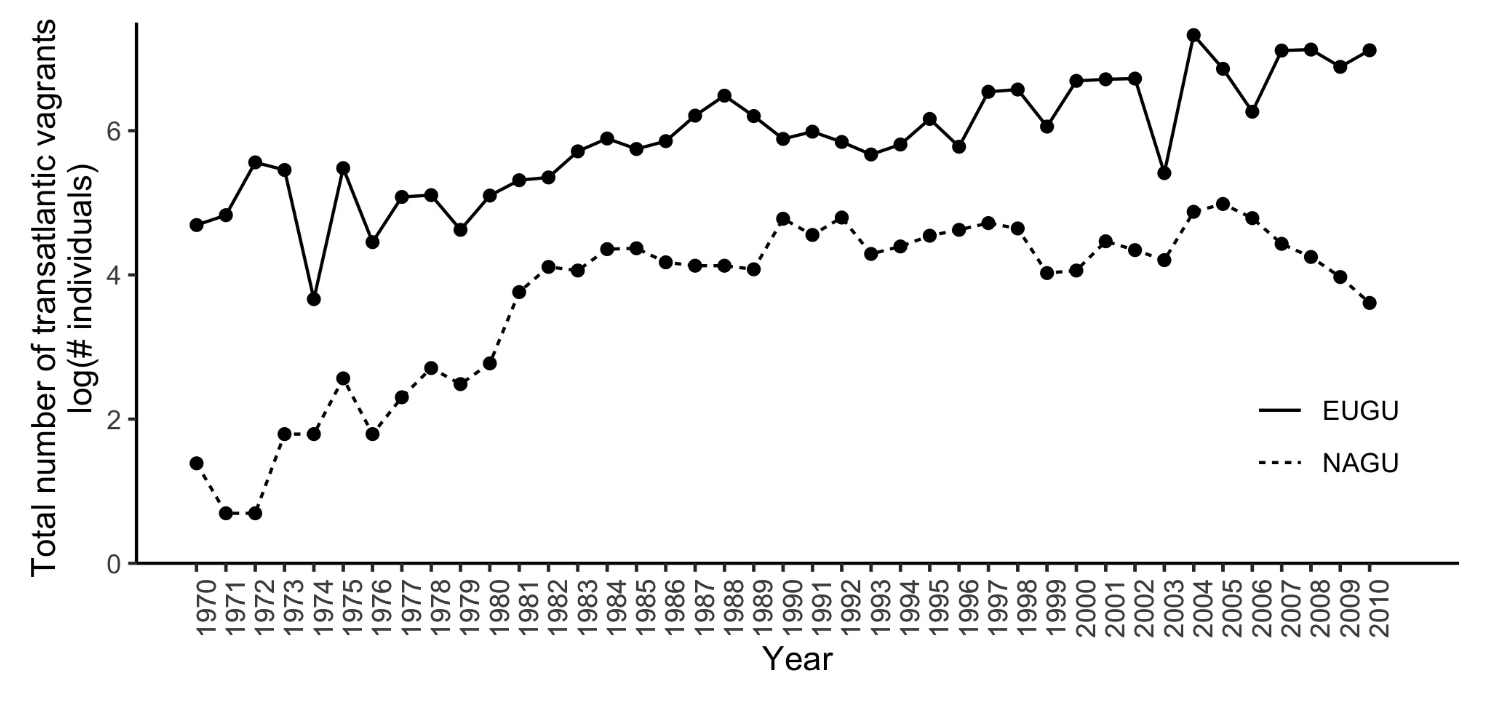

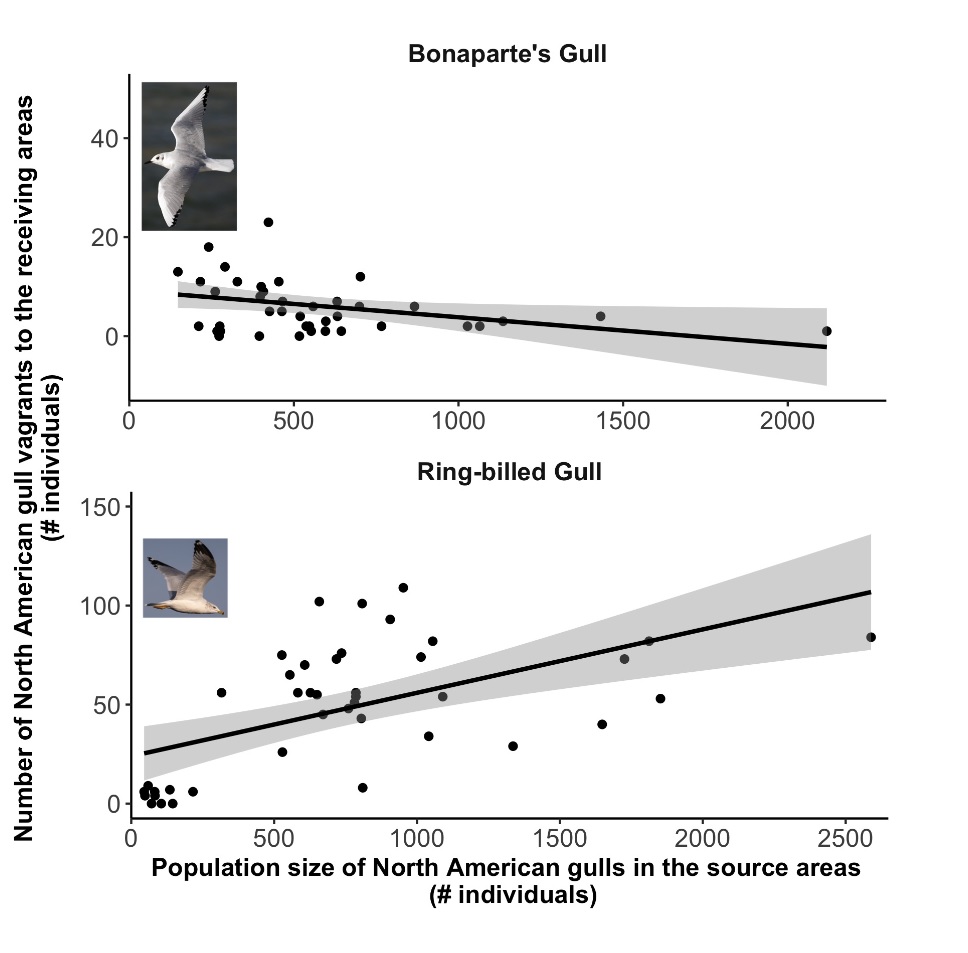

A recent paper by Alamo et al. (2022) published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution investigated the effects of population size on transatlantic vagrancy of various gull species, including our beloved Bonaparte’s gull. They hypothesized that increasing gull population sizes were directly correlated with vagrancy due to an increased pressure to explore new breeding sites. They found an increase in transatlantic vagrancy in both directions (vagrant gulls from Europe are also spotted in North America), suggesting that vagrancy is not randomly driven by strong winds, but deliberate choice.

Interestingly, Alamo et al. (2022) found an inverse relationship between the two variables when examining Bonaparte’s gull specifically. Meaning that their data suggested larger population sizes correlated with lower vagrancy rates, which contradicts their hypothesis. However, some other gulls like the Ring-billed gull (Larus delawarensis) examined in the study showed a positive correlation. The authors suspect that the population data collected on Bonaparte’s gulls might reflect the susceptibility of their nesting sites to human disturbance.

Ultimately, Alamo et al. (2022) concluded that population size is but one of many variables that can affect vagrancy of gulls; increasing population may be a necessary factor but is not alone sufficient. The authors also emphasize the importance of further research, stating that “as anthropogenic development continues, and high-quality habitats become farther apart … the persistence of a species may depend crucially on its longest-distance dispersers” (Alamo et al. 2022).

That is all, thank you for reading. Please enjoy some pictures I took of a passing Bonaparte’s gull flock in Es-hw Sme~nts Community Park here on Vancouver Island that I’m including as an excuse to shill my photography page.

References

Alamo, M. A., Alamo, M. A., Manne, L. L., Manne, L. L., Veit, R. R., & Veit, R. R. (2022). Does Population Size Drive Changes in Transatlantic Vagrancy for Gulls? A Study of Seven North Atlantic Species. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.850577

Bonaparte’s Gull. (2014, November 13). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/bonapartes-gull

Bonaparte’s Gull (Larus philadelphia)—BirdLife species factsheet. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2022, from http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/22694432

Bonaparte’s Gull Sightings Map, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Bonapartes_Gull/maps-sightings

Braune, B. M. (1987). Seasonal Aspects of the Diet of Bonaparte’s Gulls (Larus philadelphia) in the Quoddy Region, New Brunswick, Canada. The Auk, 104(2), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/104.2.167

Burger, J. (1988). Foraging Behavior in Gulls: Differences in Method, Prey, and Habitat. Colonial Waterbirds, 11(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/1521165

Burger, J., & Gochfeld, M. (2020). Bonaparte’s Gull (Chroicocephalus philadelphia), version 1.0. Birds of the World. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.bongul.01

Heydweiller, A. M. (1935). Some Bird and Egg Weights. The Auk, 52(2), 203–204. https://doi.org/10.2307/4077250

Jehl Jr., J. R. (1971). Patterns of Hatching Success in Subarctic Birds. Ecology, 52(1), 169–173. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934750

Latta, S. C., & Rodríguez, P. G. (2018). Notable bird records from Hispaniola and associated islands, including four new species. Journal of Caribbean Ornithology, 31, 34–37.

Payne, R. B., & Howe, H. F. (1976). Cleptoparasitism by Gulls of Migrating Shorebirds. The Wilson Bulletin, 88(2), 349–351.

Sandilands, A. (2011). Birds of Ontario: Habitat Requirements, Limiting Factors, and Status: Volume 2–Nonpasserines: Shorebirds through Woodpeckers. UBC Press.

Twomey, A. C. (1934). Breeding Habits of Bonaparte’s Gull. The Auk, 51(3), 291–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/4077656

Wow. I never knew that any gull species actually nested in trees. Why do they do this? Why don’t other gull species nest in trees like these guys? Is there lot’s of research into the behavior of these gulls?

Thank you for your interest Liam. Unfortunately, very little research has been done on these magnificent birds. This is likely due to the remoteness of their breeding territories combined with their general hostility to intruders on their nesting grounds. As briefly mentioned in the ‘current research’ section, human presence is thought to negatively impact the productivity of Bonaparte’s gull nesting sites; although there is conflicting evidence regarding this issue. As for why other gulls do not make nests in trees: my educated (and not at all biased) guess would be that other gull species are simply not as smart as the brilliant Bonaparte’s gull.

A great blog post, Samuel! This was well written and an enjoyable read. I will definitely be keeping a keen eye out for these birds in the future!

Loved this bird because of your enthusiasm! I am wondering, what do the gulls eat when they are up in the Boreal forests during summer breeding season? Very interesting blog.

Thank you for your interest Nicole! I am glad to see the appreciation for these birds spreading. During the summer breeding season, Bonaparte’s gulls will feed almost exclusively on insects. They catch them either off the surface of water, off of trees and smaller plants, or simply grab them in mid-air.

Very interesting. You answered my question about if they were named after Napoleon right away so I got nothin’. Well done and a great read.

Hi Sam, great post, I’m glad to see someone fighting the good fight to end the gull stigma. I feel like these guys are a good start as they’re easy to identify!