As you prepare to tee off, you notice an unlikely duo locked in a game of chicken near the first hole. On one side, a medium sized alligator, and on the other, a tall gangly bird with a fierce red cap. The bird stretches out its massive wings and walks toward the giant reptile unphased. Shockingly, the bird wins and scares of the would-be interloper. You later learn that this bird was mimicking the appearance of a human, which golf course gators are notoriously fearful of. The identity of the bird was never really a question, for it is impossible to mistake the appearance of the mighty sandhill crane.

DESCRIPTION AND IDENTIFICATION

The sandhill crane (Grus canadensis) is a member of the order Gruiformes, an ancient lineage of birds that have a rich fossil record. More specifically, they belong to the family Gruidae, which includes all cranes (All About birds, Britannica). Luckily for fledgling birders, they are an extremely conspicuous bird, especially in the northwest, where they could only be confused with the great blue heron or whooping crane. The crane’s appearance is quite unique among birds, with their tall gangly legs, huge wingspan, and elongated neck.

On the ground, adults can easily be identified by their distinctive red crown and drab grey bodies. Another distinctive feature is the drooping tail feathers that form a “bustle.” These large birds are similarly sized yet bulkier than a great blue heron but smaller than the whooping crane (All About Birds)

In the air, the sandhill crane can be distinguished from similar species by its loud “wooden rattle” call as it passes overhead (Sibley, 2016). These calls can be heard from up to 2.5 miles away! This is due to its elongated trachea that extends down into its sternum. On top of that, they can also produce moans, hisses, honks, and snores (All about birds).

There are two distinct morphs of the sandhill crane: the lesser (northern) morph and the greater (southern) morph. The lesser breeds further north and is comparatively much smaller than its southern counterpart. The greater morph’s breeding territory spans form central Canada southward and can have a beak up to 50% longer than the lesser morph. The differences are easily identified at the extremes, but Canada is home to a large intermediate population that overwinter mid-continent, and thus are difficult to ID (Sibley, 2016).

BEHAVIOUR

Sandhill cranes mate for life, and thus, have adapted a quite peculiar mating dance. To the untrained eye, their mating dance looks like an excited five-year-old after too much mountain dew. However, to a fellow sandhill crane, it is an absolutely intoxicating display. The dancing bird will stretch out their wings, bob their head, jump up and down, and call to their mate. Afterwards, females usually up to two eggs, which she will care for until they are ready to leave the nest at around nine to ten months. Wintering and migrating families have also been known to group together to form flocks, which can number in the tens of thousands (All about birds).

Another interesting behavior they have adopted is a defensive kick. Threatened individuals will begin with a warning hiss. If that fails, they resort to a kick, which involves jumping into the air and kicking their feet forward (All about birds). My younger sister employed a similar strategy in our childhood fights so I can attest to its effectiveness.

DISTRIBUTION

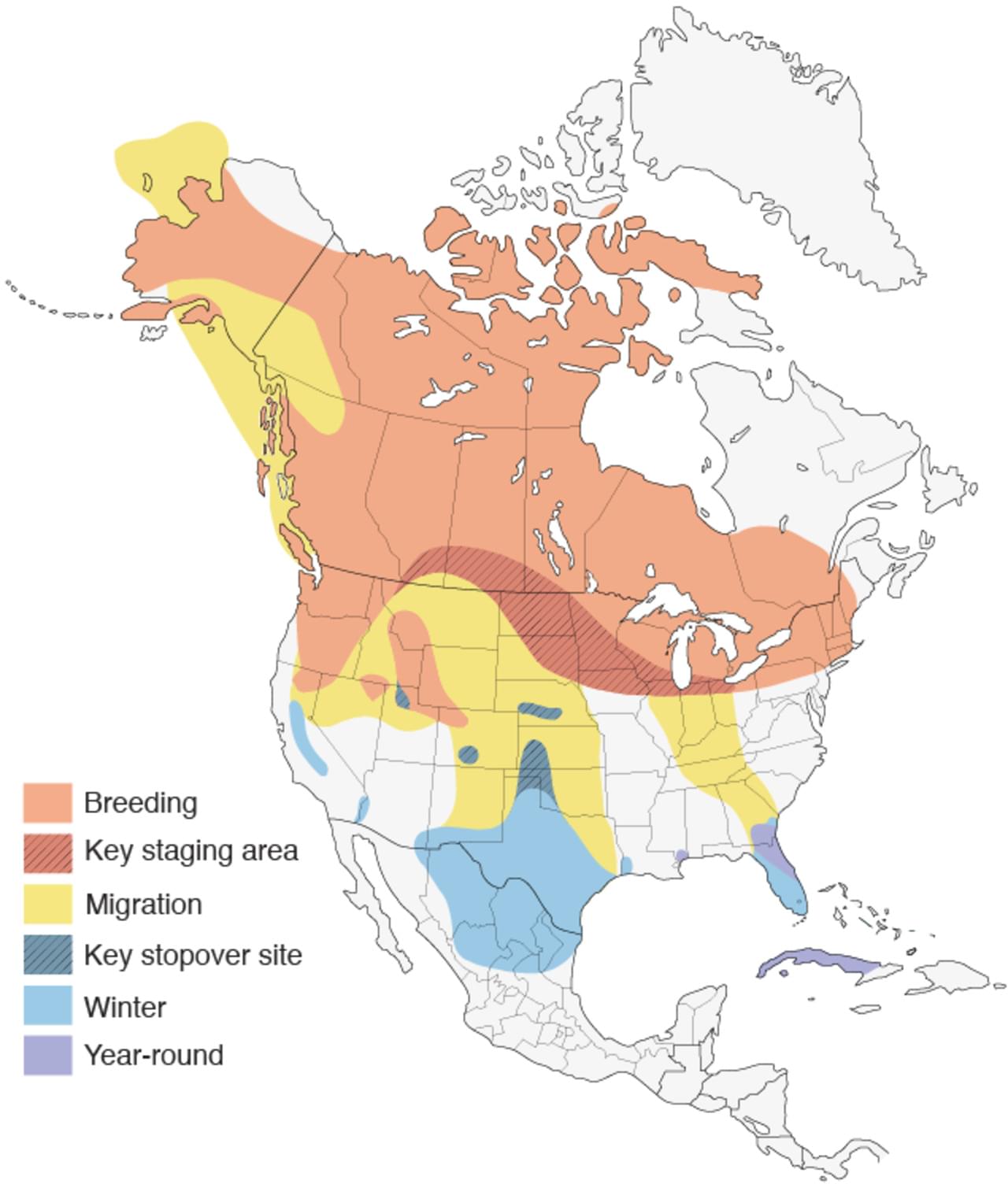

Depending on the subspecies, sandhill cranes can be long-distance migrants or residents. There are three resident subspecies, which live year-round in Florida, Mississippi, and Cuba. The three remaining subspecies will migrate far north into northern Canada and Alaska to breed, followed by a winter migration to the southern United States or Northern Mexico (All About Birds).

CONSERVATION STATUS

In general, Sandhill cranes are of low conservation concern. It is estimated that the breeding population is around 560,000 individuals (Partners in Flight). Although, the Mississippi subspecies is endangered. This is due to pine plantations taking over their wet pine savanna habitats. Like many wetland species, the biggest threat to sandhill crane conservation is habitat loss. Notably, population recovery occurs slowly due to the species’ low fecundity (All about Birds).

CURRENT RESEARCH

As if sandhill cranes didn’t have enough to worry about with the widespread loss of their wetland homes, it would seem that a clever parasite has made the jump to their species. The first report of a Protechinostoma mucronisertulatum infection in a sandhill crane has been recently described by Rothenburger et al. (2016). The parasites were found in a “debilitated, immature, male sandhill crane during autumn migration from the Canadian prairies” (Rothenburger et al., 2016).

Protechinostoma mucronisertulatum is a trematode in the family Echinostomatidae. Trematodes from this family infect a variety of terrestrial and aquatic vertebrates (Maldonado and Lanfreid, 2009). The researchers quote a report by Hoberg et al. in 2013 that suggest that migratory birds may be at increased risk for echinostomatid infection due to their limited migration path and staging areas leading to higher infection pressure.

The reason why this case is so peculiar is due to the fact that the parasite’s “normal” definitive host is the sora rail (Porzana carolina), and up until now had only ever been found in this species of bird (Redington and Ulmer, 1966; McDonald, 1981). This indicates an amazing, yet troubling, ability to adapt to new hosts. Apart from its peculiarity, the other reason for concern is the “symptoms” associated with P. mucronisertulatum infections. Severe infections in the sora rail are associated with weight loss, mild enteritis, and weakness (Toledo et al., 2006). The researchers found that the infected sandhill crane was dehydrated, emaciated, and had several intestinal perforations (Rothenburger et al., 2016).

While the lesions found in the sandhill crane could not be definitively linked to P. mucronisertulatum, the associated dehydration and emaciation could severely hamper the crane’s ability to migrate. Further research will be necessary to deduce the correlation between parasite infection and intestinal lesions. Researchers also indicated this parasite is of particular interest due to the closely related whooping-crane being highly endangered (Spalding, 1996). As such, this “one off” event must be closing monitored for it could have cascading effects in the future.

REFERENCES

All About Birds. Accessed Nov. 12, 2022. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

Britannica. Accessed Nov. 12, 2022. https://www.britannica.com

Hoberg, E.P., Kutz, S., Cook, J., Galaktionov, K., Haukisalmi, V., Henttonen, H., Laaksonen, S. (2013). Parasites in Terrestrial, Freshwater and Marine Systems. Arctic Biodiversity Assessment Status and Trends in Arctic Biodiversity, 476-505. https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publication/?seqNo115=259272

Maldonado, A. & Lanfreid, R. M. (2009). Echinostomids in the wild. The Biology of Echinostomes: From the Molecule to the Community, 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09577-6_6

McDonald, M. E. (1981). Key to trematodes reported in waterfowl. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/rp142

Partners in Flight. Accessed Nov. 12, 2022. https://partnersinflight.org

Redington, B. C. & Ulmer, M. J. (1966). Helminth parasites of rails and host-parasite relationships of the trematode Protechinostoma mucronisertulatum. Iowa Academy of Science, 73, 391–405. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol73/iss1/58

Rothenburger, L., Hoberg, E., Wagner, B. (2016). First Report of Protechinostoma mucronisertulatum (Echinostomatidae) in a Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis) from Saskatchewan, Canada. Comparative Parasitology, 83(1), 111-116. https://doi.org/10.1654/1525-2647-83.1.111

Sibley, D. A. (2016). Sibley Birds West: Field guide to birds of western North America (Second ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Spalding, M. G. (1996). Helminth and arthropod parasites of experimentally introduced whooping cranes in Florida. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 32, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-32.1.44

Toledo, R., Estebanand, J. G., Fried, B. 2006. Immunology and pathology of intestinal trematodes in their definitive hosts. Advances in Parasitology, 63, 285–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-308X(06)63004-2

Hi Colton! Lovely description of the Sandhill Crane. I was very interested in the size disparity between the bills of lesser and greater morphs, is this due to differences in feeding behaviour?

Great question! I could not find an exact reason as to the size disparity other than the fact that they are different subspecies. I would suspect that feeding behavior would contribute to the size difference.

Great read, I particularly enjoyed the opening video. I found the current research very interesting. It seems like the Sandhill Crane is experiencing more severe symptoms than the normal host, were there any deaths documented due to the parasite? If so, do you think this would hinder the chances for the species-leap of this parasite to continue?

I don’t believe so. The symptoms seen in the crane were very similar to that of the parasite’s natural host. Although, if the lesions were caused by the parasite then you may be on to something…