You’re walking through the forest, taking in the scenery of the trees, the sounds of songbirds, and observe the aquatic habitat with cattails in full bloom. Everything is peaceful and quiet; the world seems to fade away. Then, all of a sudden, you hear this strange harsh sound from far away: “kiddik, kiddik”. You shrug it off. Then, vegetation begins to move, the water starts to ripple, and the sound gets louder… You look around, but you don’t see anything! Quickly, out of the corner of your eye, you see something skitter away with a white flash and you’re puzzled to what you saw. You get out your phone and open your birding apps to investigate. To your surprise, you’ve just witnessed the rare, yet marvelous, Virginia Rail.

Figure 1: Adult Virginia Rail. Photo by Evan Lipton. Via All About Birds.

DESCRIPTION & IDENTIFICATION:

The Virginia Rail (Rallus limicola) resides in the Rallidae family which also includes the Sora (Porzana carolina), and American Coot (Fulica americana) (Sibley, 2016). Virginia Rails tend to live in marsh environments with dense vegetation in order to hide and blend with their surroundings. They have many adaptions to conquer their habitat with long legs, a long beak, and robust feathers to withstand wear and tear from the emerging vegetation (Barrett, et al., 1990; All About Birds). They also have the highest ratio of bird leg muscles to flight muscles and mainly choose to walk, or swim, rather than fly (All About Birds).

Generally speaking, the Virginia Rail is a very secretive bird, and it is more often heard than seen (eBird). The male song consists of double “kiddik” sounds that reverberate through the environment to attract female mates, much like the sound in the video below:

Video 1: Virginia Rail calling. Via naturalist97333

Physically, Virginia Rails are medium-sized and have a laterally compressed body: if you look at it head on, it looks very thin, but from the side, it looks full-bodied. This appearance led to the English idiom of looking “as thin as a rail” (Barrett, et al., 1990). Virginia Rail plumage is rusty coloured overall but with a grey face, course brown streaking along the back, black and white barring on the sides, and a white undertail (All About Birds; Kaufman & Small, n.d.). They also have a reddish beak and legs, but they are usually submerged if not covered in marsh mud (All About Birds).

DIET:

The diet of Virginia Rails consists primarily of invertebrates such as beetles, dragonflies, and snails, but they do occasionally consume seeds, fish, and aquatic vegetation (Audubon; Barrett, et al., 1990). They feed by probing through the mud and shallow water with their long beak.

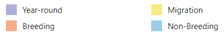

HABITAT & DISTRIBUTION:

You can find Virginia Rails across the majority of North America and in a very small portion of South America (Conway, 2020). Most Virginia Rail populations are migratory, but some on the West Coast are permanent residents (Bird Web). They tend to migrate from mid-August to October and return in the spring as early as late March. During their migration, they can be found in peculiar locations, such as in city streets (Audubon).

Figure 2: Virginia Rail distribution. Via Birds of the World

The primary habitat for Virginia Rails is freshwater or brackish marshes with water levels less than 6 inches (15cm) deep (All About Birds). They also prefer an environment with moderate proportions of emergent vegetation (30-70%) so as to not be too thick to move through (Zimmerman, et al., 2002).

BEHAVIOUR:

Virginia Rails tend to walk fast in open areas with a rather jerky motion, all while flicking their tail to display the white feathers underneath. They tend to seek cover for the majority of their time and will spend leisurely time foraging when well hidden. When Virginia Rails do decide to fly, their flight is rather short and weak. When they choose to swim, they propel themselves with their wings (All About Birds).

MATING & NESTING:

The mating ritual for Virginia Rails begins with the male running back and forth near the female with his wings raised. When both partners are in agreement, they bow to one another, and then the ritual ends when the male feeds the female (Audubon). Their nest construction is a basket made of loosely woven vegetation and placed onto dry ground or very shallow water. It is not uncommon for a canopy of live plants to be made over top of the nest for camouflage. (Audubon; All About Birds). The nests are generally located within dense vegetation for brood protection and to secure a place for foraging (Hanane, 2018) The female lays between 4-13 eggs and the young hatch with black, downy plumage – how cute! (Audubon).

Figure 3: Virginia Rail downy young. Photo by Hal Trachtenberg. Via Audubon.

CONSERVATION STATUS:

Marsh birds are wonderful indicators of marsh health and quality (Kitaif, et al., 2022). Maintenance of wetlands and degradation prevention is crucial in protecting wetland species as a whole. Mudflats, sandbars, and meadows should also be conserved as these are crucial habitats for Virginia Rail foraging and breeding (Zimmerman, et al., 2002). Populations of Rails in the past did show population decline from 1966-1991 (Courtney J. Conway, 1994) but recent evaluations show that their numbers remain stable (Bird Web). However, due to their secretive nature and small size, data collection has proven rather difficult (Courtney J. Conway, 1994). The major threat to their overall success is loss of marshland habitat, which face a major threat with global warming and climate change (All About Birds; Audubon).

Figure 4: Red list category of species vulnerability. Via eBird.

RECENT RESEARCH – PROTECT THE MARSHES!

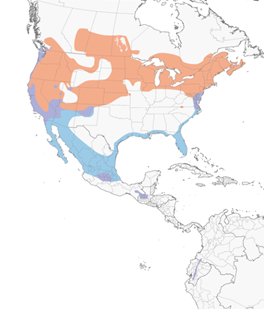

Limited research has been conducted on this marsh bird due to its secretive nature and small size. However, a recent article published in Science of the Total Environment by Kopec et al. (2018), looked into the mercury concentrations in the blood and feather of various marsh birds. The research was conducted in the lower Penobscot River in Maine, USA, specifically at a location downstream from a former chlor-alkali plant. While in operation, this plant disposed of nine tons of mercury waste into the aquatic habitat. Thankfully, the plant closed in 2000. The researchers in this study wanted to investigate mercury levels at this location in comparison to a reference site and assess how the mercury levels changed over the course of six years.

The study analyzed 5 species of birds: Nelson’s sparrow, song sparrow, swamp sparrow, red-winged blackbird, and Virginia Rails. Virginia Rails had to be captured in a different way than the “standard” mist net. This was done by luring them into open areas and then activating a woosh net remotely. A whoosh net is rapidly deployed into the air over the birds and then quickly settles to the ground to capture them. Once the birds were trapped, blood samples and feathers were collected and analyzed for their mercury content.

Figure 5: Blood mercury levels in Nelson’s sparrows (NESP), red-winged blackbirds (RWBL), song sparrows (SOSP), swanp sparrows (SWSP), and Virginia Rails (VIRA).

The results of the blood tests found that mercury levels were significantly higher in adult birds residing in habitats downstream of the previous chlor-alkali plant in comparison to the reference site. Specifically for Virginia Rails, they had mercury concentrations 10 times that of those living in the reference site – yikes! These levels were also 4 times higher compared to a similar species, the Clapper Rail. The range of mercury concentration did depend on diet differences considering the bioaccumulation of mercury through the food web.

Interestingly, it was hypothesized that mercury levels would decrease over the 6-year sampling period, but they found that levels remained stagnant or even increased! Mercury can become buried with other sediments within marsh habitats and re-suspended with changes in the river channel and erosion. This implies that the actions we take today can have disastrous effects for years, if not decades, later.

References

All About Birds: Virginia Rail. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2022, from The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Virginia_Rail/overview

Barrett, N. M., Bernstein, C., Brown, R. M., Connor, J., Dunham, K., Dunne, P., . . . Toups, J. (1990). Book of North American Birds. Pleasantville: Reader’s Digest.

Conway, C. J. (2020, March 4). Virginia Rail. Retrieved from Birds of the World: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/virrai/cur/introduction

Courtney J. Conway, W. R. (1994). Nesting Success and Survival of Virginia Rails and Soras. The Wilson Bulletin, 106(3), 466-473. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/stable/4163446?pq-origsite=summon#metadata_info_tab_contents

Fournier, A. M., Sullivan, A. R., Bump, J. K., Perkins, M., Shieldcastle, M. C., & King, S. L. (2017). Combining citizen science species distribution models and stable isotopes reveals migratory connectivity in the secretive Virginia rail. Journal of Applied Ecology, 54, 618-627. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12723

Guide to North American Birds: Virginia Rail. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2022, from Audubon: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/virginia-rail

Hanane, S. I. (2018, November 14). Evidence for a geographical gradient selection in the distribution of breeding Podicipedidae and Rallidae in the south-western Mediterranean. Journal of Natural History, 52, 2457-2472. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://doi-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.1080/00222933.2018.1539195

Kaufman, K., & Small, B. E. (n.d.). How to identify Virginia Rail. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from BirdWatching: https://www.birdwatchingdaily.com/birds/kenn-kaufmans-id-tips/how-to-identify-virginia-rail/

Kitaif, C. J., Holiman, H., Fournier, A. M., Iglay, R. B., & Woodrey, M. S. (2022, November 11). Trends in Rail Migration Arrival and Departure Times Using Long-Term Citizen Science Data from Mississippi, USA. Waterbirds, 45(1), 108-112. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1675/063.045.0113

Kopec, D. A., Bodaly, R. A., Lane, O. P., Evers, D. C., Leppold, A. J., & Mittelhauser, G. H. (2018). Elevated mercury in blood and feathers of breeding marsh birds along the contaminated lower Penobscot River, Maine, USA. Science of The Total Environment, 634, 1563-1579. Retrieved November 19, 2022 from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969718309823

Sibley, D. A. (2016). Sibley Birds West. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Thompson, G. (n.d.). Virginia Rail. Retrieved from Bird Note: https://www.birdnote.org/explore/sights-sounds/photo/2013/04/virginia-rail-0

Virginia Rail: Rallus limicola. (2021). Retrieved November 25, 2022, from xeno-canto: https://xeno-canto.org/species/Rallus-limicola

Virginia Rail. (n.d.). Retrieved November 20, 2022, from eBird: https://ebird.org/species/virrai

Virginia Rail. (n.d.). (Seattle Audubon: for birds and nature) Retrieved November 22, 2022, from Bird Web: https://birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/virginia_rail#:~:text=The%20Virginia%20Rail%20is%20a%20medium-sized%20bird%20of,reddish%20in%20color%2C%20and%20the%20cheeks%20are%20gray.

YouTube. (2012). Virginia Rail calling. YouTube. Retrieved November 23, 2022 from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kAgbhLsx5U

Zimmerman, A. L., Dechant, J. A., Jamison, B. E., Johnson, D. H., Goldade, C. M., Church, J. O., & Euliss, B. R. (2002). Effects of management practices on wetland birds: Virginia Rail. Jamestown: U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Research Center. Retrieved November 19, 2022 from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363663001_Effects_of_Management_Practices_on_Wetland_Birds_Virginia_Rail

That’s super cool! I never knew these guys had a population in South America. You mentioned that most Virginia Rails migrate from mid-August to October, but some west coast birds are permanent residents. Is there any reason why these birds choose not to migrate compared to other Virginia Rails located elsewhere?

Hi Liam! Thank you for taking the time to read my blog post.

From the information that I gathered, northern populations tend to migrate to southern USA, and those on the coast tend to stay. I believe that it is due to temperature and the likelihood of the water freezing in their habitat in the winter months. In addition to this, it was mentioned that salt marshes are a more common habitat in the winter, which I would assume is due to the lower freezing point of salt water versus freshwater. I hope this helps!

Very interesting Tana! Thanks so much for sharing.

Thank you for your comment! I hope you learned something new.

So much useful information!! I had no knowledge of this type of bird. Aweeee, how cute are they when they are babies!! I was

surprised with the color they are as hatchlings.

Thanks for all the information!

Thank you for taking the time to read my post! The breeding season for Virginia Rail’s start in May – keep an eye out the next time you are in a marsh area. The colour of the young is indeed very different from that of the adult plumage. Nonetheless, adorable!

Hey! Nice blog. I was wondering if you know why they are so elusive- does anything prey on the Virginia Rail that they might need to hide from? It was so cool to see one of these in lab. Also was surprising to me that they’re in the same family as the American Coot! Thanks for an interesting read 🙂

Hi Chloe! Thanks for reading my blog. Virgina Rails do have a large number of predators: coyotes, raptors, bears, and of course, cats! They are also considered a game species, but they are not heavily hunted. I hope this helps.

I also found that concept interesting too! The more that I learn about birds, the more interesting facts I find.

Very informative and well written post, Tana! These birds are definitely among my favorites. I was wondering, given the relative inefficacy of their flight, is a large part of their migration done on foot?

Hi Samuel! I’m glad you liked my post. That is a good question… and I could not find the answer! I would assume that they mainly fly, but perhaps do so in short bursts, but I am not entirely sure. I will definitely keep an eye out in my future readings and see if this information presents itself.