You’re on a fishing vessel 25 km off the west coast of Tofino, staring into the expansion of grey ocean surrounding you from all directions, no land in sight. Your first thought is “Oh god, I just spent over $200 to see nothing. I could have just stayed home to watch youtube videos of this for free!” As your thoughts begin to spin out of control, your tour guide starts dumping dead fish into the ocean, and that along with your oncoming sea-sickness, only adds to the nauseating feeling growing in your stomach. “There’s no way that’s going to attract any seabirds” you begin to think, “there’s nothing for miles!” At this point you’re basking in dread and ready to throw your binoculars into the ocean out of pure frustration. As you’re fighting back sea-sickness, you see a small spec in the horizon. As the shape grows bigger you see that it’s a small, silverish, angry looking bird. Excitement begins to replace the dread in your chest, as more of the same angry looking birds begin to follow. As they come closer you recognize the small bill, forked-tail, and charcoal mask covering their eyes. Pure ecstasy encases your entire body as you recognize this moment as your first glimpse of the sea-bandit itself: The Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel.

Identification

If you want to embark on the cold and wet journey of seeing a Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma furcata) with your own eyes, learning how to identify them is the perfect first step. Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels are a member of the order Procellariiformes, the tube-nose birds that are characterized by their tubular nostrils, and the ability to excrete concentrated salt in drops from their hooked bill (BCS).

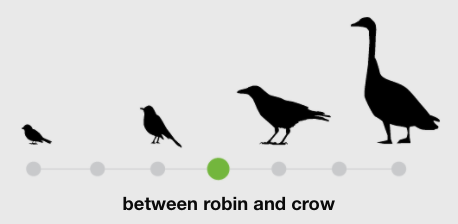

They are small for a seabird with a length of 20 cm and a weight of 50 – 80 g (think of the size between a Robin and a Crow), and size does not vary between sexes (All About Birds).

They have long, pointed wings and a long forked tail, hence their name, and a small bill and short, stubby neck (eBird). Overall, their colour is silverish-bluish gray, with darker charcoal on their shoulders and underwing, and around their eyes giving them the appearance of a mask-wearing bandit (All About Birds).

Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels are typically silent at sea, but at their nesting sites both male and female display a squeaky and harsh, descending deer-deer-deer-deer (All About Birds).

Populations from northeastern Asia to Alaska are larger and paler than populations that nest from southeastern Alaska southward, and there are intermediate birds where these populations meet (All About Birds).

Habitat and Nesting

Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels nest on remote islands in the North Pacific ranging from Alaska all the way down to Northern California. There are some large breeding colonies in the Haida Gwaii archipelago and along the northwestern coast of Vancouver Island. In British Columbia alone, there are an estimated 300,000-1.3 million individuals nesting (Nature Serve Explorer) compared to a global estimate of 4 million birds (All About Birds).

Many seabirds are known to be long distance migrants, and these guys are no exception. After spending 8 months at sea, they return to their nesting islands to breed (Nevitt, 2008). They like to use crevices of rocks, talus slopes, sod, or roots, and they even use their bills and feet to burrow into soft soil to nest in dry and enclosed locations (All About Birds).

Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels are keen recyclers, and they prove that by reusing old burrows of Tufted Puffins. Many breeding pairs do not build a nest structure, but when they do, they are very minimal, usually just comprising of grass, sedge, or other plants (All About Birds).

Reproduction

Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels are believed to be monogamous birds, usually returning to the same mate they had during the previous breeding period (Nevitt, 2008). Showmanship is very important to these birds, who immediately put on courtship displays for their special lady friend. There’s no time to waste when it comes to reproduction for these guys! They perform swift aerial chases and calls above the nest site and males will lead females toward the nest site during flight. The males will call from the entrance or from inside of their bachelor pads to entice the females to come inside. From here on out they will preen each others feathers and vocalize together, not venturing out of their nest for days; it’s a real honeymoon stage (All About Birds).

Both parents play equal roles caring for their chick after the female lays the egg (Bonadonna et al., 2007). Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels have one of the largest egg to body mass ratios of all birds, with their egg being 20% the mass of their body (All About Birds). These birds have a clutch size of just 1, so parents will give their chicks their undivided attention until its time to fledge (Nevitt, 2008). Parents will take turns incubating the egg, and provisioning the chick (Audubon). After the chick has fledged it will decide when it wants to leave the nest to take a big leap into this cruel world. Not to worry though, because this young bird will not be on their own for long (All About Birds).

Behaviour

As we know, tubenose birds have a very good sense of smell that helps them find food at sea, but however good other seabirds are at sniffing out a meal, Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels are just a little bit better. Due to their superior sense of smell, they are usually the first to respond to a crime scene – the crime scene being a smelly, floating carcass in the middle of the ocean (All About Birds).

These birds are often seen in small flocks that feed and rest on the sea surface together during the non-breeding season, sometimes mixed with other seabirds. Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels perform an interesting manoeuvre on the water called pattering. With stiff, fluttering wingbeats, they fly low to the water and hover just above the surface, pattering their feet, and dipping down to seize prey with their bill (All About Birds).

Their diet consists of planktonic crustaceans, small fish, and squid, and they have also been known to eat carrion (Nevitt, 2008). Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels will feed their chicks with oil that they store in their stomachs. The oil also has a secondary defensive purpose when the birds regurgitate the oil onto predators, or onto each other while fighting over nest sites (All About Birds). Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels, like all Procellariiformes, are known for their strong, musky scent (Bonadonna et al., 2007) that perfumes their oily plumage, their nest material and even their eggs (2008).

Remember when I said that a chick will get its parents undivided attention? Well that isn’t exactly true: Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels refuse to feed their chicks if the weather is bad. Thankfully the chicks are quite durable, and after not being fed for several days, they can reduce their body temperature and go into a stage of torpor where growth nearly stops. Once the weather clears up and mama and papa decide they can feed them, they can resume their growth (All About Birds).

Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels tend to return to their nests at nighttime to avoid predators (Bonadonna et al, 2007), even though they do not have eyes adapted for nocturnal vision (Bonadonna et al., 2003). Instead, they have powerful olfaction to attract them to food related odours, and even to help them find their burrow at night (2007) due to their attraction to the conspecific scent that covers their nest (Buxton & Jones, 2012).

Conservation

Luckily for the Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel they are a very widespread and abundant species, but little is known about their population trends (Hipfner, 2015). They have an estimated global breeding population of 4 million birds, and have a rating of 9/20 on the Continental Concern Score, so they are of least concern; However, that doesn’t mean this species isn’t susceptible to environmental disasters.

This species is known to consume floating oil from dead marine animals which makes them very vulnerable to petroleum poisoning from oil spills, which can also foul their plumage. Plastic pollution is also a concern for many seabirds, who ingest small bits of plastic that float on the oceans surface. As plastic pieces accumulate in the birds stomach, pollutants are also accumulated that can poison the birds (All About Birds).

Fun tid-bit

O ki ik is the name given to the Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels of the Bering Sea, which translates to “bird that eats oil”, due to their habit of consuming oil from carcasses of marine animals (All About Birds).

Recent Research of Fork-tailed Storm Petrels

A misconception in avian conservation is that if you are to repair a habitat after it has been damaged, birds will return to recolonize the area. Often this works, but many times it does not. Looking at avian behaviour and social factors – especially for island-nesting seabirds where strong fidelity to a site and colony is a strong part of their behaviour – is necessary for understanding social cues of these birds. Often times if these factors are interrupted, the rate of recolonization can be very limited. Seabirds like to socialize and pass on information that can lead to colonizing at new nesting sites. Once a site has seen severe damage from anthropogenic causes (such as introduced predators), they will stop sharing information that signals a good nesting site, and instead signal that the nesting habitat is destroyed. This is when they will begin looking for other, more suitable nesting habitats (Buxton & Jones, 2012).

Fork-tailed Storm-petrels use public information, such as conspecific vocalizations, when selecting a nesting habitat and like many other island birds are extremely vulnerable to predation. This is due their small size, lack of anti-predator behaviour, low reproductive rates, and ground-nesting habits. Due to social behaviour, colonies of Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels do not return after being extirpated, so it is important to understand the use of cues in forming colonies to attract individuals to an empty site (2012).

Many island ecosystems in the Aleutian chain in Alaska were devastated by the introduction of Arctic foxes, and the accidental introduction of Norway rats. The Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge has made the eradication of introduced foxes a top priority since the first successful eradication in 1949; However, the rate of storm-petrel recolonization on those islands after fox removal is decreasing. This indicates that a protocol is needed to encourage the storm-petrels to recolonize the Aleutian Islands (2012).

A colony of Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels from Ulva Cove at Amatignak, an island in the Aleutian Archipelago, were tested for their attraction to conspecific playback calls and attraction to their odours. These two cues were combined to test whether birds were more likely to enter and inhabit an artificial burrow depending on the playback and odour treatment (2012).

The Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels were strongly attracted to conspecific calls, and to conspecific odours. When two were combined, the birds entered more artificial burrows. This study highlighted the fact that it may be possible to attract Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels to abandoned colonies in the Aleutians; However, more research must be done before it can be determined whether social attraction is a suitable method for speeding up recolonization (2012).

Literature Cited

All About Birds. Accessed Nov. 26, 2020. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

Audubon. Accessed Nov. 26, 2020. https://www.audubon.org

eBird. Accessed Nov. 26, 2020. https://ebird.org

Hipfner, M. (2015). Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel. The Atlas of the Breeding Birds of British Columbia, 2008-2012. Bird Studies Canada. Delta, B.C. http://www.birdatlas.bc.ca [26 Nov 2020]

Nature Serve Explorer. Accessed Dec. 4, 2020. https://explorer.natureserve.org

Really great blog Haley!

Your description of Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels was really detailed and I don’t think I’d have any problem identifying them from your description alone. I really enjoyed reading about their nesting behaviour and locations, it’s crazy how there’s an estimated 300,000+ birds that nest on remote islands in BC alone! Did you find anything in your research about breeding-site fidelity in FTSP? I’m super curious if they usually return to the same island each breeding season.

The research was also really interesting, it was cool to read that it wasn’t only conspecific calls that attracted them, but also conspecific odours. This is great proof of their keen sense of smell and shows how useful it is for them to survive out at sea.

Thanks for teaching me more about Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels!

Maddy

Hi Madeline!

Thanks for reading my blog, I’m glad you enjoyed it! 300,000+ birds in BC surprised me too especially since they only breed on small islands off the coast.

To answer your question, Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels have very strong site fidelity and they usually return to the same nest site each year and this has a lot to do with their attraction to conspecific odours. A study I found gave the example of FTSP who had switched from a preferred soil habitat to a rocky habitat after the introduction of the Arctic Fox to their island. The FTSP would not recolonize the soil habitat even decades after the Fox species was removed even though rocky habitat decreases breeding success. This is likely due to philopatry, nest site fidelity and conspecific attraction, so FTSP would rather return to the existing colony in rock habitat year after year rather than recolonize soil habitat on their own.

I hope this answers your question!

Haley

Drummond, B. A., Leonard, M. L. (2010). Reproductive consequences of nest site use in fork-tailed storm-petrels in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska: Potential Lasting Effects of an Introduced Predator. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 5(2), 4.

Hi Haley,

Really great blog! I loved learning about the Fork-tailed Storm Petrel. Awesome introduction and I found your whole blog post very easy to read and follow. You mentioned that the chick will decide when to leave the nest and that it would be on its own, but not for long. What were you referring to when you said that?

Also do you know why the parents refuse to go out in bad weather? Is it just because they don’t want to risk getting lost or stuck at sea?

Thanks for the great post!

Danielle G

Hi Danielle!

Thanks for reading! I’m glad you enjoyed it. I was referring to FTSP spending their time with other seabirds while they are out at sea during the non-breeding season. So after they leave their nest, they are not on their own for long as they go to find other FTSP and sometimes other species of seabirds that they end up foraging with.

From my understanding, parents will feed their chicks at night-time after returning from 4-6 days of food scavenging. Since they do not have nocturnal vision it can be risky to return to the nest and they rely on conspecific olfaction. If they weather is bad they are probably less able to navigate their way back to their nest safely which would increase their likelihood of being a victim of predation. So they probably wait until the weather clears up to return to their nest to increase their longevity. More research would need to be done on FTSP parental care before your question can be fully answered.

I hope this helps,

Haley

All About Birds. Accessed Dec. 6, 2020. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

Bonadonna, F., Hesters, F., Jouventin, P. (2003). Scent of a nest: discrimination of own-nest odours in Antarctic prions, Pachyptila desolata. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 54, 174-178.

Bonadonna, F., Miguel, E., Grosbois, V., Jouventin, P., Bessiere, J, M. (2007). Individual Odor Recognition in Birds: An Endogenous Olfactory Signature on Petrels’ Feathers? Journal of Chemical Ecology, 33, 1819-1829.

Buxton, R. T., Jones, I. L. (2012). An Experimental Study of Social Attraction in Two Species of Storm-Petrel by Acoustic and Olfactory Cues. The Condor, 114(4), 733-743.

Thank you Haley, very cool!

I have to admit, you had me at the fishing boat story, I really feel as though I resonated at a spiritual level with that piece. I can’t believe that a bird that small produces an egg that massive, no wonder they only lay one per year.

You mentioned that the Fork-tailed Storm Petrels will regurgitate oils to discourage predators as well as defending nest sites. I was wondering if you found anything regarding if the oil regurgitated has any sort of chemically harmful composition, or if it is purely defense by discomfort?

Thanks for the super interesting blog!

James

Thanks for reading my blog James, very cool!

I’m glad you enjoyed the intro, I had a lot of fun writing it! I agree, it can’t be comfortable to lay an egg that big.

To answer your question, the oil’s primary function is to feed chicks so it does not have a chemically harmful composition. It is made up of digested substances and when used defensively it is apparently done with “enthusiasm and stunning accuracy”, so it seems as though it is a deliberate attack to defend what they believe is rightfully theirs.

I hope that answers your question!

Haley

All About Birds. Accessed Dec. 5, 2020. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

Boersma, P. D., et al. (1980). The Breeding Biology of the Fork-Tailed Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma furcata). The Auk, 97(2), 268-282.

Hi Haley, cool borb!

Very well written and easy to read, even for someone who doesn’t know much about birds at all. You mentioned that another name for Fork-tailed storm petrels is O ki ik, where does this name originate from?

I’m looking forward to your reply 🙂

Hi Moritz!

Thanks for reading, I’m glad you found it informative! The name comes from indigenous peoples in the Bering Sea from I believe Alaska.

Thanks 🙂

Haley

All About Birds. Accessed Dec. 5, 2020. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

Thanks Haley I’m SUPER happy you answered my question!

Merry Christmas 🙂

Moritz

Hi Haley,

Lovely blog! These guys are pretty elegant. I think I am always partial to grey-ish birds, they are always so simply beautiful. The little screams of the nestling FTSP in your video nearly stopped my heart… TOO CUTE!!

I find it really interesting that their clutch size is only a single egg. Did you come across anything in your research as to why this was the best strategy for them? Seems pretty risky to place their bets on a single egg.

Well done, and thank you for sharing your love of FTSP!

Cheers,

Sam

Hi Sam!

Thanks for reading, I’m glad you enjoyed it! Yeah these guys are some nice looking birds, I find many tube-nose birds to be kind of special! I agree, that little FTSP chick was adorable!!

Yeah it seems very risky to have such a small clutch size but there is actually a very little rate of clutch failure among FTSP, as the chicks are quite durable. Both parents take equal care of the chick after the egg has been laid, with taking turns incubating the egg, to taking turns going on foraging trips and remaining at the nest to take care of the chick. Since so much parental care has to go into taking care of one offspring it would be unmanageable with two, and would likely to lead to the death of one or to both offspring. Instead they put all of their effort into successfully raising a single chick and it seems to be working!

I hope this answered your question,

Haley

All About Birds. Accessed Dec. 6, 2020. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

Muack, R. A., et al. (1995). Monogamy in Leach’s Storm-Petrel: DNA-Fingering Evidence. The Auk, 112(2), 473-482.

Hey Haley,

Awesome bird! I’ve never had the pleasure of seeing one of these birds for myself, but if I ever do in the future I’ll know what they are! I’m surprised at how many individuals there are, I would have thought that a species that breeds only on the small locations of the western coast of North America would have a relatively small population! I was wondering where they spend their time during the non-breeding season. Do they spend it entirely out at sea, or do they migrate down the coast or across the ocean?

Thanks for the great blog!

Adam

Hi Adam!

Thanks for reading, I’m glad you enjoyed it! I also can’t believe how many there are in such a seemingly small area. FTSP are generally not a migratory species and they usually spend the non-breeding season out at sea, but they do not migrate to different islands or down the coast. They spend 8 months in the Northern Pacific Ocean during the non-breeding season and they only return to land to breed. Unfortunately, not much is known about the their range during the non-breeding season so it isn’t specifically known where they spend most of their time when they’re out at sea.

I hope this answers your question!

Haley

All About Birds. Accessed Dec 6, 2020. https://www.allaboutbirds.org

Hi Haley! This was super cool to read about!

Since FTSP are monogamous, do they find another mate if their current one dies, or do they no longer breed after that?

Thanks for the awesome read!

Hi Erika!

Thanks for reading! I wasn’t able to find any research on whether FTSP will find a new mating partner if their current one dies; However, it seems likely to me that FTSP would seek out a new mating partner for fitness gains so as to increase their parity. The reason FTSP are monogamous is because they are unable to provide parental care for 2 eggs at the same time, and this is also why they have a clutch size of only 1 egg. So if one of the parents were to partake in extrapair copulations it is very likely that only one or neither of their eggs would survive. This would not increase their parity therefor, they stick to one mate. They form a life-long pair bond with their mate, so I am not sure how that would effect their desire to increase their parity after their mate dies, so more research would have to be conducted in order to properly answer your question.

Sorry I couldn’t really answer your question but I hope you find this answer somewhat insightful,

Haley

Sorry, I forgot the citation.

Muack, R. A., et al. (1995). Monogamy in Leach’s Storm-Petrel: DNA-Fingering Evidence. The Auk, 112(2), 473-482.

Hey Haley,

Awesome blog and I loved your intro. The video of the chick was so cute and the fluttering/hovering behaviour was really interesting to watch. Similar to Adams question, do these guys spend their time out at sea mainly flying or do they spend much time resting and floating in the water? Also, I can’t imagine trying to carry an egg 20% my body mass – that’s crazy.

Thanks,

Kirsten

Hi Kirsten!

Thanks for reading! Yeah I am glad I found those videos, I’m happy you enjoyed them. As I mentioned in my response to Adam, very little is known about the behaviour and range of FTSP during the non-breeding season. It is known that they spend most of their time with other seabirds foraging for food. They are considered to be non-migratory species, as they spend all their time in the Northern Pacific Ocean when not at their nesting colonies. Since they are non-migratory I am guessing that they do not spend most of their time flying, but rather foraging or resting on water. Though, they are only out at sea for 8 months of the year so they could spend much of that time flying. More research would have to be done in order to answer your question as the distance they travel during those 8 months is unknown.

I hope this helps,

Haley

All About Birds. Accessed Dec. 6, 2020. https://www.allaboutbirds.org