Part I: Introduction

The Orange-crowned Warbler is one of 54 warbler species found across North America. The warblers are part of the order Passeriformes, and all but one warbler species, are part of the family Parulidae. Warblers are known as one of the smallest kinds of birds found within North America. The Orange-crowned Warbler (Leiothlypis celata) is known for traveling long distances, heading South during Fall migration (Sibley 2016).

Description & Identification

The Orange-crowned Warbler is a small songbird with a sharp pointed bill. It has been described as the plainest warbler species. It has an olive coloration on its upperparts and more of a yellow coloration on its underparts. Overall, Orange-crowned Warblers can be quite plain in terms of colour patterns. As for the under tail covert feathers, these feathers are typically bright yellow. On the Pacific coast Orange-crowned Warblers have been described as having a more yellowish appearance than those that are farther East. Taking a closer look, Orange-crowned Warblers have a faint, thin yellow, or white stripe over the eye as well as a faint black streak that appears to pass though the eye, and a very pale eyering. Despite its name, the Orange-crowned Warbler typically does not have a noticeably visible orange crown; very rarely can an actual orange patch be seen . However, an orange patch on the crown of the warbler’s head may become visible if the bird raises its feathers in response to stimuli causing excitement or agitation to the bird (Audubon Field Guide). An Orange-crowned Warbler can range in length between 3 to 5.5 inches, and weigh between 0.3 to 0.4 oz. Lastly, the warblers wingspan is equal to approximately 7.5 inches for both males and females (Sibley 2016). (eBird)

Like many warbler species, the Orange-crowned Warbler can be found foraging within thick shrubs and low-growing vegetation including small trees. This species has been referred to as being quite quiet and rather inconspicuous. Often times, however, it can be spotted when foraging within low vegetation. They can also be heard making low volume contact calls to one another while scavenging. The Orange-crowned Warbler’s call can be described as a high pitch “chip” sound (Jones 2007). Whereas its song is considered a trill, meaning when they sing, it’s a series of quickly repeated high notes (eBird).

The Orange-crowned Warbler is an insectivore, meaning that its main diet is composed of insects such as various types of ants, flies, caterpillars, beetles, and other invertebrate prey such as spiders. If the Orange-crowned Warbler encounters a shortage of insects, they can alter their diets and eat other food sources such as fruits, seeds, and other forms of vegetation. They have been known to also visit sap wells made by types of woodpeckers such as the sap sucker. Orange-crowned Warblers may, at times, be attracted to backyard feeders or may attempt to retrieve nectar from flowering plants. (The Cornell Lab)

Distribution, Habitat & Nesting

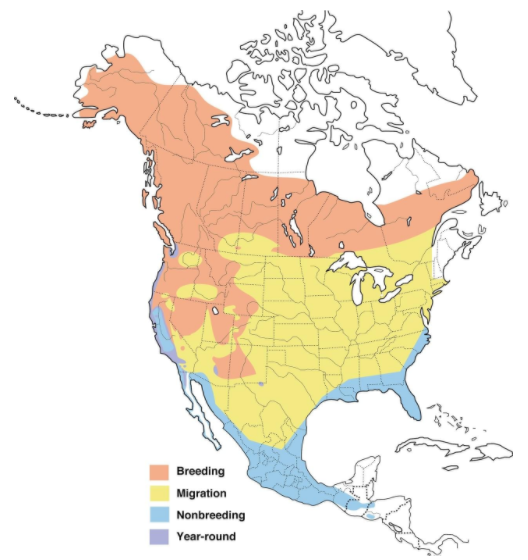

As mentioned previously, the Orange-crowned Warbler can typically be found in areas with low-growing vegetation growing in riparian ecosystems, meaning situated along the banks of rivers and streams. The Orange-crowned Warbler species is considered to be widespread in shrubby habitats across Canada, Alaska, and throughout the western United States. During the Fall/ Winter migration, these birds are known to migrate South towards the southern United States and down to Central America. (The Cornell Lab)

The Orange-crowned Warbler spends its breeding seasons throughout Canada, Alaska, and the western United States (Sibley 2016). During the fall migration season, the Orange-crowned Warbler migrates its long journey South. They begin their travels during the night. As warblers travel South, many of them chose to winter in Mexico, while others continue their journey further South, choosing to spend the non-breeding season either in Guatemala or Belize. Some warblers that breed on California’s Channel Islands, will spend their winters in the northern and southern regions of California. (The Cornell Lab)

The Orange-crowned Warbler can call a wide variety of habitats home. It can be seen forming habitats within alders or willow trees that are scattered within old-growth temperate rain forests in parts of Canada and up to Alaska during their breeding season. In Arizona, the Orange-crowned Warbler has been reported in fir-aspen woodlands up to 7,500 ft. These Warblers have been known to breed in open, logged, or clear-cut areas in the northern Rockies. The Orange-crowned Warbler breeds in forested habitats and prefers shrubbery and other low-growing vegetation. During the winter seasons, the Orange-crowned Warbler seeks a warmer climate such as that in areas of the southern United States, and Mexico. (The Cornell Lab)

When it comes to nesting, the female warbler is typically the one to choose nesting sites. As she flutters amongst low-growing vegetation, she is seeking a nesting location that includes a shady hillside, is near steep trail cuts, located in a gully, or a canyon that is sheltered by vegetation. Nests are then built on the ground under plants, nestled in tree roots or amongst fern fonds, on moss, within rock cracks, or dips in the ground soil. Some warblers may even form their nests off the ground, placing them within low-growing shrubs. (eBird)

Once a nesting location has been selected for, it is time for the female warblers to build the nests. The nest building process can take up to four days to complete, resulting in a nesting cup that is approximately 4 inches across and 2.5 inches high. In order to build the nest, the female, Orange-crowned Warbler must first lay down a foundation. The foundation of the nest is comprised of a variety of materials such as stems, dead leaves, grasses, and various other coarse materials. The foundational materials are then weaved together in order to create a solid outer shell. The nest is then lined with finer materials such as animal hair, or finer grasses thus, providing a cozy nest for future eggs. Once the nests have been built, the female will lay her eggs. Typically, a clutch size can range anywhere from 3 to 6 eggs. The eggs are a creamy color with very fine reddish-brown speckles. Once the eggs hatch, the hatchlings emerge from the eggs with their eyes closed, and their bodies covered in sparse dark gray down feathers. (The Cornell Lab)

Behaviour

Although small, these songbirds are known for flying rapidly through shrubs, vines, and trees, snatching insects from leaves as they go. Orange-crowned Warblers typically feed from their perches, but they can grab insects as they fly through the air. They poke and prod through decaying leaf litter and through moss and bark using their sharp bill, in hopes of finding hidden invertebrate prey (Remsen et al. 1989).

During the spring, males begin their vocalizations and will sing their trill song, in order to establish their territories and attempt to attract a mate. In order to defend their territories or when threatened, males will lift the feathers on their crown in order to display their bright orange crown. If a male manages to attract a female, the two will begin their silent courtship. During the courtship phase, the males perform mimicry, and attempt to mimic the females movements by performing several actions such as dropping their wings, pointing their bill towards to sky, and spreading their tail feathers. If the males courtship efforts are successful, a pair will be established. Orange-crowned Warblers have been known to mix with other types of warblers, chickadees, vireos, etc. during winter or while migrating. (The Cornell Lab)

Conservation Status

Although the Orange-crowned Warbler is considered to be relatively abundant within its breeding range, the populations have declined by approximately 34% between the years of 1966 and 2014. Some areas of the United States have experienced steeper declines in Orange-crowned Warbler populations. As of 2014, the Orange-crowned Warbler was not noted as a species of bird that should be watched closely. Researchers have noted that these warblers likely benefit from logging practices in certain areas, for it creates openings in forest canopies thus, leading to an increase in low-growing vegetation, which is their preferred habitat. However, practices that damage shrubbery or low-vegetation can result in the lost of suitable habitat for this warbler species. Additional causes of death in Orange-crowned Warblers can be attributed to building collisions, or collisions with vehicles, towers, and wind turbines. (The Cornell Lab)

Interesting Facts

- There are four subspecies of Orange-crowned Warblers. Each subspecies differs in plumage coloration, size, and molt patterns. One subspecies can be found in Alaska and across Canada during breeding season. This subspecies is considered to have the dullest coloration of all and contains the most gray. The other subspecies can be found on the Pacific coast (brightest yellow), throughout the Rocky Mountains (intermediate appearance), and in southern California (greenest coloration)

- The oldest Orange-crowned Warbler recorded was a male and was estimated to be at least 8 years and 7 months old when recaptured during banding processes in the state of California. The average lifespan of the Orange-crowned Warbler is estimated to be 6.8 years old, and does not vary between sexes.

- Orange-crowned Warblers typically build their nests on the ground or in low-growing vegetation, this is potentially to avoid nest-robbing bird ie. depredation. However, the southern Californian subspecies will form their nests in taller shrubs and trees due to there being potentially less aviation predators present and in order to escape predation from snakes and mammals on the ground. (The Cornell Lab)

Part II: Current Research

Genetics & Evolution

Molecular Evidence that the Channel Islands populations of Orange-crowned Warblers represent a distinct evolutionary lineage

As mentioned previously, four subspecies of the Orange-crowned Warbler have been identified across North America. This study used molecular data in order to assess the degree of divergence of a particular subspecies (Oreothlypis celata) across its western North American breeding range. This study was particularly interested in investigating the degree to which O. celeta populations diverge with one another between the maintain of southern California and the Channel Islands. This study used sequences of mitochondrial DNA and genotypes for various population of all four recognized subspecies. The results indicated that there was in fact significant divergent results, albeit shallow divergent results. The results indicate that the subspecies located on the Channel Islands of California do experience isolation and isolation-by-distance which can explain the genetic divergence of the populations located on the Channel Islands in comparison to those located on the mainland of southern California. Great gene-flow was observed in Channel Island populations as oppose to those located on the mainland. (Hanna et al. 2019)

Post-breeding Molt

Post-breeding elevational movements of western songbirds in Northern California & Southern Oregon

Migratory species such as the Orange-crowned Warbler must employ a variety of strategies in order to meet the high cost energetic demands that is required for post-breeding molt processes. This study investigated the strategies employed by western Neotropical migrant species such as the Orange-crowned Warbler. These species are known to travel a short upslope distance to areas of higher altitude, where adults will then molt both their body and flight feathers. This phenomenon is suggested to be quite common yet may be poorly documented. This study aimed to examine the prevalence of short-distance molt migration in higher altitudes in Neotropical species. Previous collected data was used to create linear models for nine Neotropical species including the Orange-crowned Warbler. The study aimed to examine whether elevation and the distance travelled from the coast, can be used to predict the abundance of of breeding and molting birds. Research results suggest that long-distance migrants such as the Orange-crowned Warbler moved higher in elevation in order to complete their post-breeding molt. The study concluded that changes in altitude for molt migration are quite common, it is variable among species, and is a rather complex behavioural characteristic amongst western songbirds. (Wiegardt et al. 2017)

References:

Gilbert, William M., Mark K. Sogge and C. Van Riper III. (2010). Orange-crowned Warbler (Oreothlypis celata), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Hanna, Z. R., Cicero, C., & Bowie, R. C. K. (2019). Molecular evidence that the channel islands populations of the orange-crowned warbler (oreothlypis celata; aves: Passeriformes: Parulidae) represent a distinct evolutionary lineage. PeerJ, doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.viu.ca/10.7717/peerj.7388

Jones, J. (2007). Orange-crowned Warbler Singing in October. Colorado Birds, 40.

Orange-crowned Warbler Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved November 23, 2020, from Orange-crowned Warbler Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Orange-crowned Warbler, Audubon Field Guide, Audubon. Retrieved November 23, 2020, from Orange-crowned Warbler | Audubon Field Guide

Orange-crowned Warbler, eBird. Retrieved November 23, 2020, from Orange-crowned Warbler – eBird

Remsen, J., Mark Ellerman, & Cole, J. (1989). Dead-Leaf-Searching by the Orange-Crowned Warbler in Louisiana in Winter. The Wilson Bulletin, 101(4), 645-648. Retrieved November 27, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4162799

Sibley, D. (2016). Orange-crowned Warbler. In Sibley birds west: Field guide to birds of western North America (2nd ed., p. 372). New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Wiegardt, A., Wolfe, J., Ralph, C. J., Stephens, J. L., & Alexander, J. (2017). Post-breeding elevational movements of western songbirds in northern California and southern Oregon. Ecology and Evolution, 7(19), 7750-7764. doi:10.1002/ece3.3326

Awesome job Gabrielle!

Your blog was a really in-depth and detailed look into the lives of orange-crowned warblers and I learned a lot. I found it really interesting how adaptable these little guys are at finding a food source. It almost seems as though they can eat nearly anything depending on what’s available in their environment!

The conservation information you provided was also really intriguing, it makes sense that some orange-crowned warblers actually benefit from forestry practices due to the creation of their ideal habitat. You mentioned that despite not being exceptionally endangered, their populations have still decreased 34%. Did you find any possible explanations for this decrease or was it mainly the collisions you mentioned?

I really enjoyed reading your blog, thanks for sharing!

Maddy

Hi Maddy,

Thank you for your interest in my blog post! In terms of conservation, I was only able to find the following causes for population decline. The population is estimated to have declined by about 34% from 1966 to 2014. As mentioned, some forestry practices such as the deforestation of large trees eg. California Redwood, have increased the shrubbery able to grow within the area, thus; creating the Orange-crowned Warbler’s ideal habitat. However, some forestry practices (eg. In Alaska), have led to the destruction of the forest understory, thus; destroying the Orange-crowned Warbler’s habitat, and leading to a decline in possible nesting sites. So loss of habitat due to forestry practices that destroy the forest understory has led to a decline in the population. Additional deaths can be attributed to collisions as mentioned. Although 34% would appear to be quite a decline in the population (1966 – 2014), they are still considered to be of low concern in terms of conservation. The global breeding population has been estimated to be equal to 80 million, globally (Partners in Flight, 2017).

Hope this helps to answer your question. Thank you again for your interesting in the Orange-crowned Warbler!

Gabby

Hi Gabrielle,

Nice blog. These guys are one of the most common species we catch at Buttertubs, but I still haven’t got tired of them! I’ve always loved their delicate eyeliner look.

Do you know if these guys suffer greatly at the hands (or wings…) of brood parasitism? Madi’s blog mentioned COYE parasitism by BHCO, and I’m curious if OCWA, with their wide range, are a favourite victim of these brood parasites.

Thanks for sharing your love for OCWA!

Cheers,

Sam

Hi Sam,

Thank you so much for your interesting in the Orange-crowned Warbler! As mentioned in Madi’s blog post on the Common Yellowthroat, the Brown-headed Cowbird is well known for it’s brood parasitism behaviour. Looking into, I did find that the Orange-crowned Warbler has also experienced this type of parasitism by the Brown-headed Cowbird. The Orange-crowned Warbler builds its nest on the ground or in low-growing vegetation, making it easy for brood parasites to prey upon. The Brown-headed Cowbird will lay it’s eggs within the nests, and may even remove some of the OCWA eggs. The Orange-crowned Warbler will then go on to incubate the eggs and once hatched, will provide food for the hatchlings. Unfortunately, the Brown-headed Cowbird will out compete the Orange-crowned Warbler offspring. So unfortunately, yes, the Orange-Crowned Warbler, much like the Common Yellowthroat, does suffer at the hands (or wings) of brood parasitism.

Hope this helps to answer your question. Thank you again for your interest in my blog!

Gabby

Hey Gabrielle,

Great blog! It was interesting learning more about the Orange-crowned warbler. I found it intriguing that the oldest recorded Orange-crowned warbler was 8 years and 7 months old. I was wondering how this compares to their average lifespan? I also noticed that the oldest one recorded was a male, do you know if there is a difference in lifespan between gender for this species?

Thanks,

Tyler

Hi Tyler,

Thank you for your interesting in my blog! That’s a great question. So, the average lifespan of the Orange-crowned Warbler has been estimated around 6.8 years old, and does not appear to vary between sexes.

Hope this helps!

Thank you again for your interest in the Orange-crowned Warbler