Introduction:

Killdeer are perhaps one of the most notable and widely spread shorebirds in North America. They are a rather active and noisy plover that can often be found far from the shore (All About Birds). They also boast a rather unique name, however, don’t let them fool you, these little guys can’t actually take down a deer.

Description:

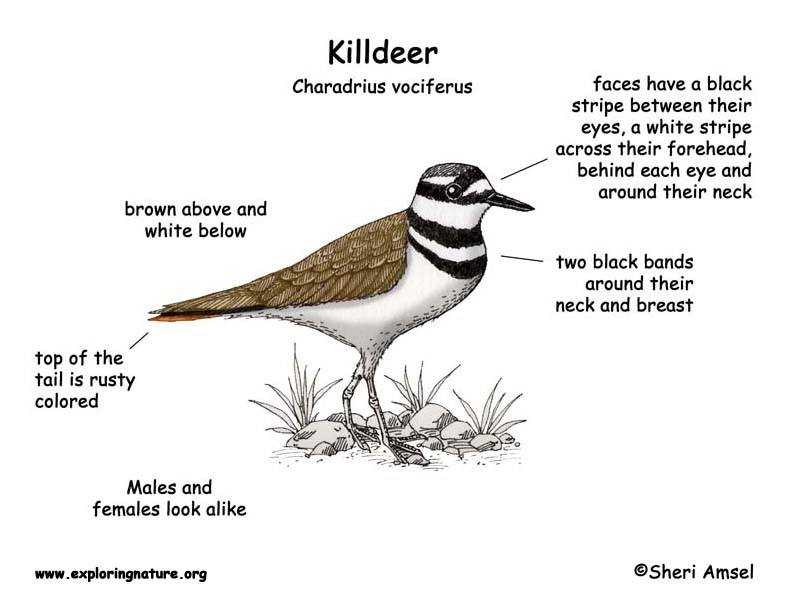

Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus) are slender robin-sized birds belonging to the family of Charadriidae. This family of birds falls under the common name of plovers, which may be familiar to some readers. They exhibit the typical plover feature of having a short bill. However, they have a uniquely large and round head and eyes. They also have rather lanky legs along with a long pointed tail. Killdeer are averaged size plovers with a weight between 75-128g, a length between 20-28cm, and a wingspan between 46-48cm (All About Birds). Killdeer may be called shorebirds, yet they are often found far from it as they can be spotted in short grass fields far from water or even gravel parking lots (Sibely, 2016). While Killdeer have a somewhat misleading common name, their scientific name describes them perfectly, as Charadirus refers to frequenting the shore, and vociferous means clamorous and noisy, which they most definitely are (Jobling, 2010).

Identification:

The most distinct feature of Killdeer is the two black bands wrapping around their lower neck and breast. Note that the two black bands are only present in adults as juveniles will only have one. In addition to this, they also have two distinct black stripes on their face. Other than these features Killdeer are rather plain with their above being a boring shade of brown with a white bottom and a rusty rump/tail when in flight. It should also be noted that males and females of this species appear the same, meaning they are monochromatic, so sexing from a distance is a lost battle. Although one may think the black bands might separate Killdeer from other shore birds, they are often confused with other plovers, such as Wilson’s plover and the Semipalmated plover (All About Birds). However, these birds only have one measly black band located at the base of their neck. So if you’re ever stuck between the three look out for those two distinct bands.

As some may already be familiar with, Killdeer did not get their name from a unique prey item. Rather Killdeer actually named themselves, as their call is described as “kill-deer”(eBird). In addition to calling their name, they also have a shrill “kill-deee” or “fill-deee”. Along with a call of “dee, dee-duh-duh” or “deet-deet-deet” and a sputtered alarm call when protecting their nest (Audubon.org).

Habitat and Distribution:

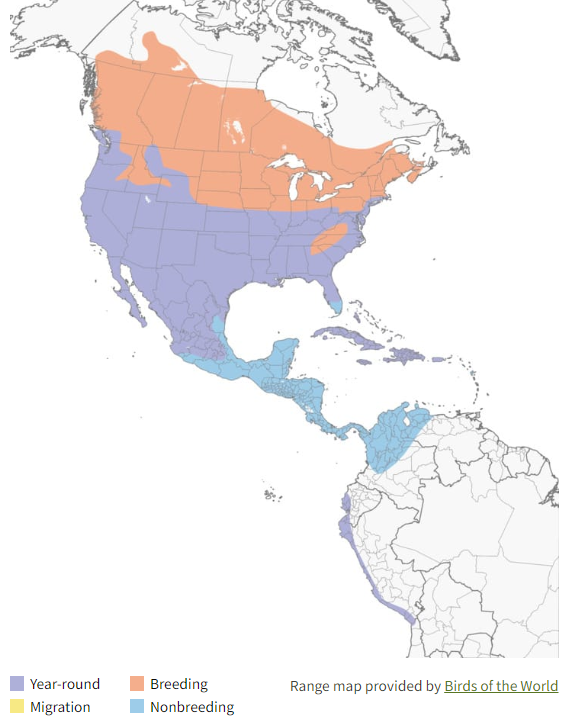

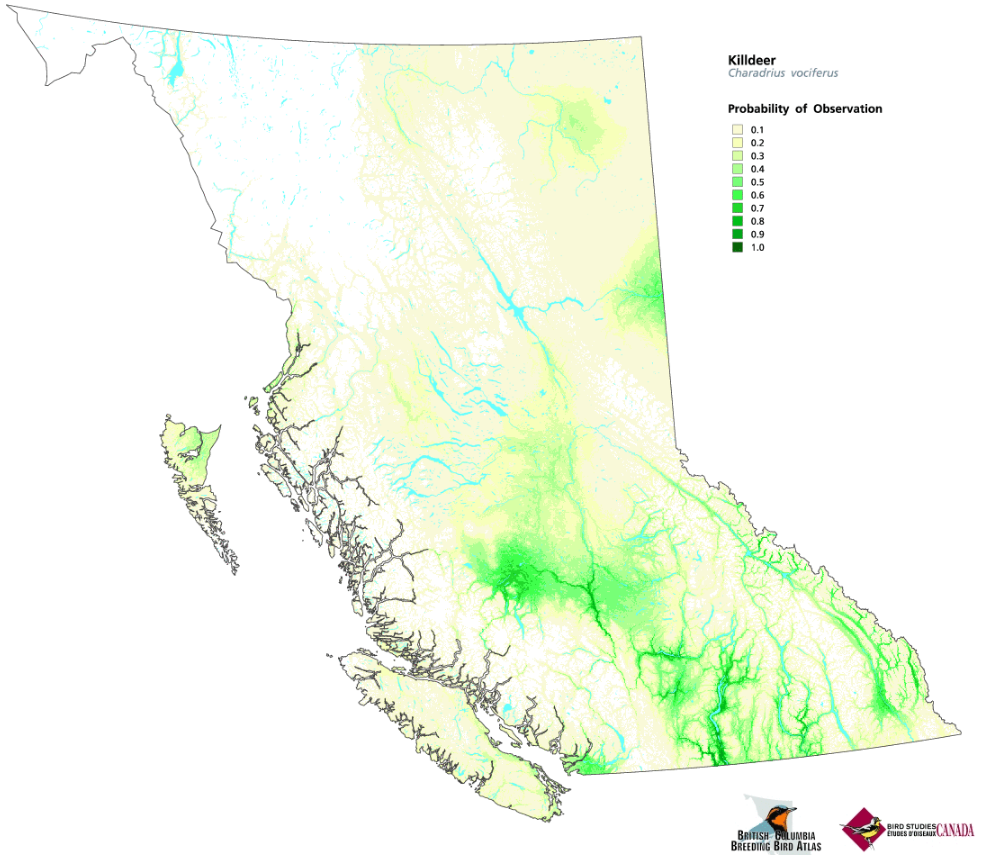

Killdeer can be found as far north as northern Canada and as far south as northern South American coasts. They are known to breed in Canada and the United States where they are also year-round residents, making sightings likely for us here on the island. There are also some year-round residents in parts of Mexico. Some northern breeding Killdeer may also choose to spend their winters in Mexico (All About Birds). In British Columbia specifically, Killdeer have been found to breed in the southern third of the province. Generally mirroring the distribution of agriculture and human development (Atlas of the Breeding Birds of British Columbia). As previously mentioned, Killdeer are shore birds meaning they often inhabit shore environments such as sandbars and mudflats, like the ones our class saw at Englishmen River Estuary. However, they can also be found in agricultural crops, pastures, short-grass prairies, as well as wetlands, and open grasslands (New Hampshire PBS).

Behaviour

Killdeer are mostly spotted feeding during the day either alone, in a breeding pair, or in a loose grouping during non-breeding seasons, however, they are also known to be active during night hours (Animal Diversity Web). Killdeer are ground foragers typically observed on flat landscapes using a stop-and-go technique of running and then stopping and pecking around to search for prey such as insects or earthworms, they will also tap their foot to stir up anything nearby. When inhabiting farmland they will sometimes follow tractors to search for upturned prey, which is a very unique behaviour (American Bird Conservancy). They are often thought to be carnivores as they do primarily feed on insects, crustaceans, and terrestrial or aquatic invertebrates. When in reality they are omnivores as they have been known to feed on berries (Animal Diversity Web). Their flight is stiff with intermittent wingbeats, and when they are disturbed they will take off and circle overhead while calling, especially if the disturbance is near their nest (All About Birds).

Mating and Nesting

Male Killdeer, similar to most birds, will attract a mate by producing a loud call to attract females. As well as performing their scrape ceremony near potential nests made by the male (All About Birds). Once a female selects a male they will remain monogamous during their given nesting season and may nest together in the future (Wild Bird Watching).

Killdeer make basic scrape nests somewhere in their typical open habitat where they will also forage for food, these nests are generally between 3-3.5 inches across. They often make multiple different nests before deciding on one, using the others as decoys for predators (All About Birds). Scrape nests are different from the stereotypical bird nests found in trees. A scrape nest is a simple depression made in the ground with added stones or leaves (Golden Gate Audubon Society). Killdeer will typically produce a clutch of anywhere from 4-6 eggs and will have 1-3 broods over a year. Interestingly, once Killdeer begin to lay their eggs they will usually add rocks, trash, shell pieces, or sticks to the nest, and they have a specific preference for lighter-coloured additions (All About Birds). Scientists believe there are two reasons behind this, one being thermoregulation of the nest as the white colour will reflect light and keep their often unshaded nest cooler. And two for a form of concealment by creating cryptic colouration around the nest to better hide it in plain sight. (Kull Jr, 1977).

Killdeer are precocial birds, meaning that juveniles hatch with their eyes wide open ready to move around, and are covered in downy feathers. This doesn’t mean they are instantly ready for flight as they can only run around and still depend on their parents (birdwatching.com). Parental Killdeer do not feed their young, which is rather unusual, chicks instead follow their parents and begin practicing their foraging ability. After approximately 31 days chicks will leave the nest, however, sometimes they stick around for an extra 10-day period (birdfact.com).

The Iconic Broken Wing Act

If readers knew anything about Killdeer before reading this blog it would’ve either been about their call or their very unique broken-wing act. Which is performed by adults who will pretend to have a broken wing in order to distract predators from the nest by hobbling away from it to protect their young (All About Birds). This behaviour is thought to be a reflex function of Killdeer occurring when an enemy intrudes on their breeding territory as the behaviour is not entirely dependent on the presence of eggs. However, it isn’t solely a reflex as there are some learned nuances since there are slight procedural differences depending on the intruder (Deane, 1944).

Conservation Status

Killdeer populations have experienced a noticeable decrease since 1970, The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) lists Killdeer as a candidate wildlife species for assessment, due to their general decline in population. They have also been identified as a priority for conservation in more than one Bird Conservation Region Strategy in Canada. However, globally Killdeer have been deemed a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Government of Canada). This is largely due to the lack of dramatic population change. As their population only decreases by an estimated 0.57% per year, with a global population of an estimated 2.3 million. They are also thought to be one of the most successful shorebirds due to their fondness for human-modified habitats, as previously mentioned. Sadly, there is a downside to their fondness as it makes them more susceptible to pesticide poisoning or collisions with cars and buildings (All About Birds).

Fun Facts:

- The oldest Killdeer on record was at least 10 years and 11 months old when it was released after a recapture at a bird banding operation in Kansas

- Adult Killdeer are actually rather proficient swimmers and chicks are able to swim across small streams often found on the coastal environment they may inhabit (All About Birds)

Recent and Future Research on Killdeer

Dancing in the Moonlight

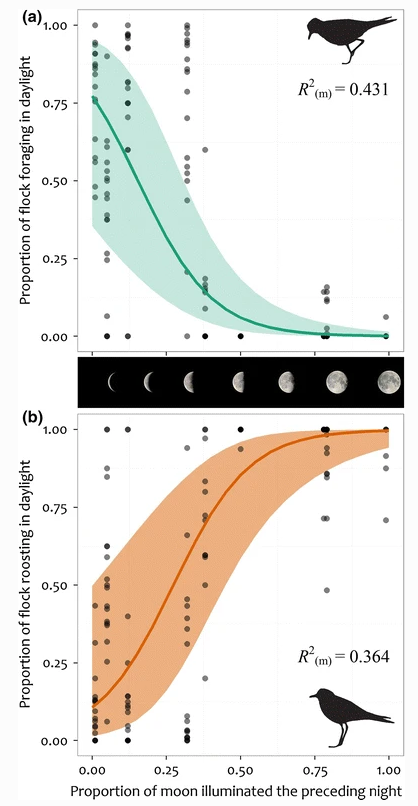

As previously mentioned, Killdeer forage by searching the ground for prey items, thus relying on sight and sufficient illumination of the ground. However, a study conducted in California suggested Killdeer may actually prefer foraging during the night in order to avoid predation and optimize prey availability, as their prey items are more active at night. Not only did it suggest that they preferred foraging at night, but that they actually understood lunar cycles and would be more active on nights with brighter moonlight for better foraging. The study found that all models including lunar illumination were supported, rejecting the null hypothesis of there being no link between lunar illumination and Killdeer night foraging behavior. It also found that diurnal foraging decreased and diurnal roosting increased following nights with better lunar illumination. Which highlights an important link between lunar cycles and the diurnal activity of Killdeer. It is also proposed that anthropogenic light pollution may lead to changes in shorebird foraging entirely, as there is more artificial light at night possibly exposing birds to nocturnal predation. Which could have serious trophic system consequences. (Eberhart-Phillips, 2016)

Figure 8: Killdeer Behaviour Following Nights with Varying Levels of Illumination. Via Luke J. Eberhart-Phillips.

Anthropogenic Effects on Killdeer Ecology

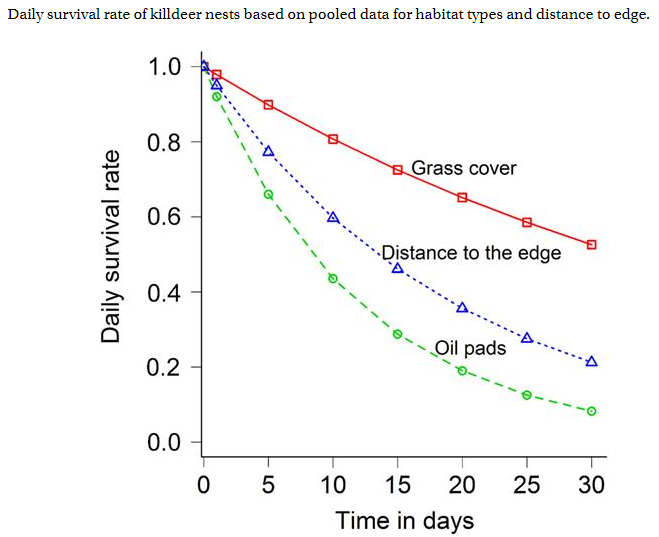

Most readers should already be aware that human development almost always has serious impacts on the surrounding environment and species that call that environment home. Sadly, Killdeer are not immune to these impacts as anthropogenic developments and disturbances are threatening their habitats and populations. A study conducted in Oklahoma looked at the effects of oil and natural gas extraction on Killdeer nest survival by comparing survival estimates of those that nested on graveled oil pads (gravel surrounding oil extraction sites) versus native grass-covered fields. The study revealed that Killdeer had a preference for nesting on the gravel oil pads over natural grass environments, showing that 64% of nesting attempts were on oil pads. It was also found that nest survival estimates of oil pads were lower than in the grassy environment due to human activity as workers may step on or drive over nests. In this sense, human-modified landscapes act as traps for animals such as Killdeer, as they are attracted to the environment but suffer greatly while inhabiting it. Future management efforts to reduce human impacts on bird species is highly encouraged as it would be beneficial to all parties if conservation planning was incorporated with natural gas or oil extraction plants (Atuo et al., 2018).

Another study conducted in North and South Dakota looked at the displacement or attraction that wind energy facilities have on birds as well as the density effects on 9 different grassland bird species, one of which was Killdeer. It was found that Killdeer expressed attraction for wind turbine facilities at two sites 1 year after construction. As Killdeer are typically attracted to human-occupied environments they had no problem tolerating these new human-made facilities. It was also found that their density increased closer to newly constructed sites. Data on the impacts of wind turbine facilities on different bird species can contribute to well-informed site planning in the future, as it may seem to have positively impacted Killdeer, these sites also displaced different species of birds that did not react positively to human disturbance (Shaffer & Buhl, 2015).

Conclusion

Overall, I hope readers are able to take away some unique knowledge of a very characterisitic bird that is often overlooked when compared to more iconic birds, such as a Bald Eagle or a Blue Jay. Maybe this could even act as some reader’s gateway into birding or bird conservancy efforts. Thanks for reading!

References

A pair of Killdeer, at West Delray Park. (n.d.). Animals Network. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://animals.net/killdeer/.

Atuo, F. A., Saud, P., Wyatt, C., Determan, B., Crose, J. A., & O’Connell, T. J. (2018). Are oil and natural gas development sites ecological traps for nesting killdeer? Wildlife Biology, 2018(1), 1–8. https://bioone-org.ezproxy.viu.ca/journals/wildlife-biology/volume-2018/issue-1/wlb.00476/Are-oil-and-natural-gas-development-sites-ecological-traps-for/10.2981/wlb.00476.full

Burger, A. E. (n.d.). BC Breeding Bird Atlas. BC Breeding Bird Atlas Home Comments. Retrieved October 27, 2022, from https://www.birdatlas.bc.ca/accounts/speciesaccount.jsp?sp=KILL&lang=en#:~:text=The%20breeding%20range%20extends%20across,(Jackson%20and%20Jackson%202000).

Chung, T. D. and H. (n.d.). Charadrius vociferus (killdeer). Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Charadrius_vociferus/

Cotton, J. J. (n.d.). Killdeer On Shore. Hoolden Forests & Gardens. Retrieved October 24, 2022, from https://holdenfg.org/nature-profiles/killdeer/.

Danielson, B. (2020). Killdeer. Greenfield Recorder. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://www.recorder.com/Speaking-of-Nature-33574610.

Deane, C. D. (1944). The broken-wing behavior of the Killdeer. The Auk, 61(2), 243–247./https://sora.unm.edu/node/18681

Eberhart-Phillips, L. J. (2016). Dancing in the moonlight: Evidence that killdeer foraging behaviour varies with the lunar cycle. Journal of Ornithology, 158(1), 253–262. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.viu.ca/article/10.1007/s10336-016-1389-4

Grove, M. (n.d.). Kill Deer Nest. Nest Watch. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://nestwatch.org/connect/participant-photo/kill-deer-nest/.

Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm. London. Pg. 32. 404. https://archive.org/details/Helm_Dictionary_of_Scientific_Bird_Names_by_James_A._Jobling

Killdeer. American Bird Conservancy. (2020, July 17). Retrieved October 25, 2022, from https://abcbirds.org/bird/killdeer/

Killdeer. Audubon. (2022, April 1). Retrieved October 30, 2022, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/killdeer

Killdeer(Charadrius vociferus). Canada.ca. (2015, August 19). Retrieved October 29, 2022, from https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/bird-status/oiseau-bird-eng.aspx?sY=2014&sL=e&sM=p1&sB=KILL

Killdeer – Charadrius vociferus – natureworks. New Hampshire PBS. (n.d.). Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://nhpbs.org/natureworks/killdeer.htm

Killdeer – eBird. (n.d.). Retrieved October 24, 2022, from https://ebird.org/species/killde

Killdeer nesting (all you need to know). Birdfact. (n.d.). Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://birdfact.com/articles/killdeer-nesting

Killdeer nesting mating and feeding habits. Wild. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2022, from https://www.wild-bird-watching.com/killdeer.html

Killdeer Overview, all about birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved October 23, 2022, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Killdeer/overview

Kull Jr, R. C. (1977). Color Selection of Nesting Material by Killdeer. The Auk, 94(3), 602–603. https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v094n03/p0602-p0604.pdf

Shaffer, J. A., & Buhl, D. A. (2015). Effects of wind-energy facilities on breeding grassland bird distributions. Conservation Biology, 30(1), 59–71. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291356720_Effects_of_wind-energy_facilities_on_breeding_grassland_bird_distributions

Sheri, A. (n.d.). Killdeer Idenitification. Exploreing Nature Educational Resource. Retrieved October 23, 2022, from https://www.exploringnature.org/db/view/Killdeer.

Sibley, D.A. 2016. Sibley Birds West: Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, New York. pg. 124.

The precocious killdeer. (n.d.). Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://www.birdwatching.com/stories/killdeer.html

Types of bird nests. Golden Gate Audubon Society. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2022, from https://goldengateaudubon.org/conservation/make-the-city-safe-for-wildlife/tree-care-and-bird-safety/types-of-bird nests/.

YouTube. (2010). A Good Mother Killdeer. YouTube. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UcJB4sWVykQ&ab_channel=natureswaiting.

YouTube. (2022). Killdeer foraging. YouTube. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MPSglHdHHd0.

YouTube. (2022). Killdeer- courting ritual. YouTube. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6PumQM4MCow&ab_channel=NatBel.

Extremely informative. I now know something about a bird I never fully considered as being present in this area. I will now be alert to its presence.

Thanks, glad you enjoyed it, it really is fascinating how much goes on in nature without us realizing it.

Very informative, I was not aware of this species before!! I will be sure to keep my eyes peeled from now on.

For northern BC populations, you mention some will migrate all the way to Mexico. Does Northern BC possess a permanent population as well? Do some also instead migrate to southern BC or similarly less distant areas?

Thanks, happy to hear you learned something new from it. From the research I did, it seems that there are no year-round residents in northern BC, however, not all northern residents migrate to Mexico, as it’s more common for them to return to southern BC or parts of America.

What a neat shorebird! Their ability to rely on lunar cycles and use the night time sky illumination for to their advantage is really cool. I would be interested to learn more about the patterns of year-round Killdeer and if the longer nights and cloud-cover (particularly in southern BC) during the winter are factors in the night time forarging habits.

Thanks for reading, I definitely agree, I would’ve never thought that shorebirds would be so active at night I thought it was just owls that behaved that way. That is a great point, I’m willing to bet any factor influencing lunar illumination will play a role in their nighttime foraging ability. However, further studies would need to be conducted to get to the bottom of this.

Cool blog, I never really gave birds much thought but I learned a lot from this

Thank you, hopefully I piqued your interest enough to get you to come birding with me someday.

Great job! I learned about the broken wing thing from an episode of Kenny vs. Spenny, glad to see Kenny knew what he was talking about.

Thank you, that’s definitely a unique way to learn about birds haha.

well done Codey, this was very informative. That broken wing act is incredibly interesting, do you know if this act is preformed equally between mated pairs?

Thank you, from what I read it seems whichever one is roosting will be the one to perform the act.

Hey Codey, awesome blog. The broken wing act is fascinating! Would be so cool to witness it in person!

Thanks, glad you enjoyed it! Yeah, you’d have to get your timing right, but it would be special to see it in person.

Do you know if their behaviour/ tendency to be in a group is different between the coastal populations and the Eastern Canada populations that are found in grasslands/ farming areas?

That’s a great question, I didn’t read anything that specifically mentioned the difference in behavior between Western and Eastern Killdeer. But that would be an interesting research question for sure. Thanks!