Merlin Description

Merlins (Falco columbarius), are fierce and clever falcons that span the Northern Hemisphere. Merlins are among the smaller members of the falcon family, yet they use their small size to their advantage with incredible maneuverability and powerful flight. They are excellent hunters and intimidate even birds that are too big to be preyed on. They are intelligent birds and have been used in falconry since the Medieval Times (All About Birds).

Identification

Merlin are smaller than crows but make up for it with their robust build. Colour is highly dependent on geography and thus is not a great identifier, additionally, populations and individuals may lack certain defining features depending on their plumage.

To distinguish merlin from other birds of prey it is most useful to observe their overall stature, movements and take a good look at the patterns on their underwing, chest and tail.

Immature males and adult females can be difficult to distinguish from afar due to similar plumage. Adult females are considerably larger than adult males, up to 35% larger by mass, and they are additionally more brown in colour than adult males (Lusby et all., 2017).

Key Identifying Features: (All About Birds)

Wings: Sharply pointed. Often dark and checkered.

Tail: Medium length, contrasting stripes, white terminal stripe.

Chest: Lighter than back, thick streaks. Under chin and base of the tail are paler in colour.

Eyebrow: Lighter tone than the rest of the plumage, less visible in the prairie subspecies.

Mustache: Resembles a crowbar mustache. Less visible in lighter subspecies.

Quick Tips to Avoid Misidentifying a Merlin in Flight

North American Subspecies

There are 9 subspecies of merlin globally. The three shown are found in North America

Photo by Ryan Merrill

Distribution and Habitat

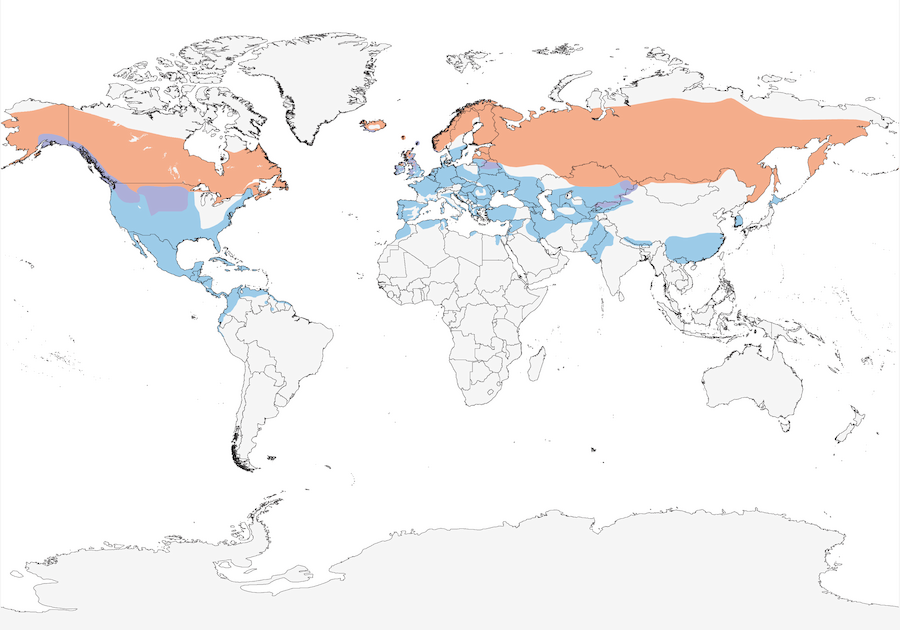

Merlin breed in the northern latitudes of North America, Europe and Asia. Migratory populations overwinter in the southern latitudes of the northern hemisphere (All About Birds).

Merlin require an open or semi-open landscape for hunting. When available merlins nest in semi-open forests in close proximity to grasslands, bogs, coastlines, rivers and anthropogenic environments (Konrad et al., 2020).

Merlin populations are increasing in urban areas likely due to a high abundance of songbird prey (Konrad et al., 2020).

Map found on: Birds of the World

Purple= Year Round,

Red= Breeding Range,

Blue= Non-Breeding Range

History in Falconry

In medieval Europe, the merlin became popular in falconry despite its small size. The merlin is unable to fetch large game, but they excel in hunting small-medium sized birds such as songbirds, quail and possibly ducks (All About Birds). In the late 1400s, the merlin became known as “the falcon for a lady”, referencing a published guide to the sport in which societal classes were recommended an appropriate falcon. Less commonly referenced is that Emperors were also recommended merlins, in addition to eagles and vultures (Clark, 2022).

In the current day, merlins continue to be a favourite in falconry, a sport that remains somewhat prevalent in some countries including the United States and Canada. Exact requirements vary by region, but both countries regulate the impact of falconry on merlin populations by issuing permits and licenses based on population estimates (Konrad et al., 2020).

Photo by Alexander Abuladzee

A Year in the Life

Hatchling’s

It’s hard to believe that these balls of the fluff will grow up to be fierce predators, but with the help of their parents, they will grow very quickly into successful hunters.

The merlin will remain nest-bound for at least a month before their flight feathers come in and they can begin to fly! Clumsy at first the fledglings will practice flight around the nest by chasing insects and other birds (All About Birds).

Close calls in the 2021 BC Heat Wave

During the B.C heatwave of 2021 Avian rehab centers across the province rehabilitated hundreds of birds, including falcons.

Due to the high temperatures, many hatchlings were said to have jumped from their nests prematurely. Many received injuries during the fall or suffered from severe dehydration and hunger (Labbe, 2021).

Migration

Each population of merlin chooses to spend their winters differently. Most black merlins are residents and opt to stay close to their breeding ground all year. Most taiga merlin migrate to the south-central United States or as far as Central America. Migratory populations generally follow migratory paths along mountain ranges or follow coastlines (Bourbour et al., 2021). Merlin are primarily solitary outside of breeding season but they may migrate in loose groups (All About Birds).

Merlin have relatively small fat reserves so they must hunt throughout their migration, in order to fuel their journey. It has been shown that young Merlin intentionally follows the same migratory route as their songbird prey, even when their prey alters their path. Few, if any studies have explored if this behaviour continues into adulthood (Bourbour et al., 2021).

Breeding Season

Returning to the Breeding Grounds

Males return from winter first, preparing to claim territory before the females return from the south. Males are more likely to return to the same area to breed as the previous year, fewer females opt to return (Konrad et al., 2020).

Finding a Mate…… or not

Males attempt to win over females by showing off their hunting and flying skills; performing showy dives, and slow flutter flights. They also show off their tail and wings, figure eight around a potential mate, or offer her food (All About Birds). First-year males have little luck finding a mate, probably due to their small size, inexperienced hunting skills, and inferior nesting site. More first-year females will breed but may have a smaller nest or end up mating with another first-year. By the second year, males are nearly fully grown, and most will successfully find a mate. (Warkentin et al., 2016).

Many find comfort in knowing merlin, among other falcons are monogamous. Unfortunately, it’s not so cut and dry, in fact, there’s less than a 20% chance the breeding pair will remain together (All About Birds) for two years in a row. Another blow to monogamous animal lovers is the reports of extra-pair copulations amongst merlin during the breeding season. That means that a merlin from outside the breeding pair; typically an outsider male will breed with the female while her mate is out hunting (Sodhi, 1991). While merlin may not be faithful they are reliable! A breeding pair is truly socially bound and will continue to raise and protect their young together, no matter the funny business going on amongst them (Sodhi, 1991).

Photo by: Rhododendrites

A Merlin showing off his chest, possibly to impress a potential mate.

Photo by: Rhododendrites.

Choosing the Perfect Nest

Merlins are frugal when it comes to nesting season. Instead of building their own nests they utilize abandoned crow, raven, magpie and hawk nests. They choose nests in semi-open forested areas so they can keep watch on the surrounding area. In desperate times they may choose a nest in a tree cavity, on a cliff or on the ground (All About Birds). Older individuals often get the first pick of available nests, leaving the smaller undesirable ones to the young inexperienced birds (Warkentin et al., 2016).

Defending their Territory

Both sexes are highly defensive of their nesting territory. They do so by soaring high above the area and making frequent calls. Merlins successfully intimidate other species away from their nesting territory. The area surrounding merlin’s nests have a lower bird abundance, even in species that are not preyed upon by merlin. This is likely due to merlin’s intimidation tactics, or simply because other species don’t want to risk injury by being the next victim of hunting practice (Sodhi et al., 1990). The home range appears to depend on prey abundance, with merlins who nest near sufficient food requiring a smaller range (Konrad et al., 2020).

The mating pair will each choose a favourite perch in their territory and make frequent calls to each other.

Nesting Time

1-2 months after returning home it is time to start nesting. Females lay 2-5 brown eggs (All About Birds). The female spends the majority of her time defending the nest but will occasionally switch out when her partner brings her food (Konrad et al., 2020). The eggs are incubated for about 1 month until they hatch, then the parents will continue to provide parental care for the remainder of the summer (Konrad et al., 2020).

Conservation and Research

Conservation Status

According to the North American Bird Breeding Survey, Merlin populations are steadily increasing. Like many raptors, their population suffered from pesticide contamination in the 1960s. Currently, they are categorized as Low Concern (All About Birds). However, they are a difficult species to study and changes to their environment may harm the population (Lusby et all., 2017).

New Forests in Ireland may Harm Merlin Populations

In Ireland, forest cover is actually increasing! This has some worried about the health of Irish Merlin populations, as it’s known that they heavily rely on open and semi-open habitats for hunting (Lusby et al., 2017).

Investigating the impact of a loss of foraging habitat revealed a lot about the merlin’s breeding and foraging behaviours. When comparing long-term population trends it was shown that with an increase in conifer plantains, Irish merlins have started to use nests on the forest edge rather than nest on the ground as they did previously. However the proximity of the open habitat to their breeding grounds still heavily influences nest selection, it was found that an open habitat within 5km of their nest positively influences breeding success. This study also found that merlin do not nest in forests that are younger than 11 years old, and they vastly prefer forests between 31 and 40 years old (Lusby et al., 2017).

Overall, it appears that so far merlin in Ireland are not negatively affected by increased forest cover. However, their populations should be considered when mapping out the location of new conifer plantations, as they still heavily rely on some form of open landscape to forage (Lusby et al., 2017).

Graph 1: Proportion of land type within 10km square blocks occupied by a merlin pair, 2km from their nest, and 500m from their nest.

Literature Cited

- Bourbour, R. P., Aylward, C. M., Tyson, C. W., Martinico, B. L., Goodbla, A. M., Ely, T. E., Fish, A. M., Hull, A. C., & Hull, J. M. (2021). Falcon Fuel: Metabarcoding reveals songbird prey species in the diet of Juvenile Merlins (falco columbarius ) migrating along the Pacific coast of western North America. Ibis, 163(4), 1282–1293. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12963

- British Columbia. (2022, January 24). Natural Resource Online Services. Capture Live Wildlife for Falconry and Zoos – Activity Guidance – Natural Resource Online Services. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from British Columbia. (2022, January 24). Natural Resource Online Services. Capture Live Wildlife for Falconry and Zoos – Activity Guidance – Natural Resource Online Services. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://portal.nrs.gov.bc.ca/web/client/-/possess-live-wildlife-for-falconry

- Clark, A. (2022, January 14). History of falconry. Raptor Aid. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.raptoraid.com/about-the-birds-1/history

- Cornell University. (2022). Merlin overview, all about birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Merlin/

- Konrad, P.M., Shaffer, J.A., and Igl, L.D., 2020, The effects of management practices on grassland birds—Merlin

- (Falco columbarius), chap. R of Johnson, D.H., Igl, L.D., Shaffer, J.A., and DeLong, J.P., eds., The effects of management practices on grassland birds: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1842, 12 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/pp1842R.

- Labbe, S. (2021, June 30). Birds jumped out of their nests to escape the June heat wave. Prince George Citizen. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.princegeorgecitizen.com/highlights/birds-jumped-out-of-their-nests-to-escape-the-june-heat-wave-4183127.

- Lusby, J., Corkery, I., McGuiness, S., Fernández-Bellon, D., Toal, L., Norriss, D., Breen, D., O’Donaill, A., Clarke, D., Irwin, S., Quinn, J. L., & O’Halloran, J. (2017). Breeding ecology and habitat selection of Merlin falco columbarius in forested landscapes. Bird Study, 64(4), 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2017.1408565

- Simpson, F. S. (2014, June 25). Sounds and Sonograms. Merlin (Falco columbarius) sonogram > fraser’s birding website. Retrieved November 12, 2022, from http://www.fssbirding.org.uk/merlinsonogram.htm

- Sodhi, N. S. (1991). Pair copulations, extra-pair copulations, and intraspecific nest intrusions in Merlin. The Condor, 93(2), 433–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/1368960

- Sodhi, N. S., Didiuk, A., & Oliphant, L. W. (1990). Differences in bird abundance in relation to proximity of Merlin nests. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 68(5), 852–854. https://doi.org/10.1139/z90-123 (Sodhi et al., 1990)

- Warkentin, I. G., Espie, R. H., Lieske, D. J., & James, P. C. (2016). Variation in selection pressure acting on body size by age and sex in a reverse sexual size dimorphic raptor. Ibis, 158(3), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12369

Hi Kaitlyn! You mentioned in the falconry portion that they were/are very common birds in falconry, but that they can only catch smaller prey. Was there any advantage they had to their keepers in terms of hunting? or was it primarily the sport of training them to fly including their small size making them good to keep?

Hi Chloe,

The initial hierarchy was likely assigned simply because the Merlin is very small, therefore a great falcon for women (sigh). However modern hobby falconers don’t typically recommend Merlin as one’s first bird because their smaller size makes weight management a concern for inexperienced falconers. Their highly variable personalities can also make them more difficult to train for beginners.

Experienced hobby falconers enjoy keeping Merlin because of this challenge, and they are exciting and fascinating to work with. They tend to have calm demeanours once trust is gained, and their powerful and highly maneuverable flight makes them great hunters. They will also take on whole flocks and chase for longer distances.

They are among the best hunters in open areas but I’m not sure if they brought back more food overall since their prey is generally smaller. But nowadays it’s primarily a hobby so it’s just the falconer’s preference, and many are won over by the merlin’s charm.