Anna’s Hummingbird belongs to the genus Calypte, which also includes the species Costa’s Hummingbird. Both C. anna and C. costa display courtship behaviour that includes diving displays. The courtship behaviour of these hummingbirds has been researched extensively as it is incredibly interesting!

A male adult Anna’s hummingbird perched and ready to learn about diving displays! [Link]

Observations done by Stiles1 & Clark2 defined these activities. It was noticed that there is an initial contact made by the female in which she will fly into the male’s territory and try to feed.1 While the female is in the males territory she will evaluate its quality. She will then be approached by the male whereby he will proceed to sing to her with his gorget flared, perform a “shuttle” display, and then partake in a series of outstanding diving displays.3 These performances may result in copulation if the male is lucky! The “shuttle” display is described as a back-and-forth motion above the female, while producing a high-intensity song.1 This display is said to be the most crucial part of courtship! The diving display consists of the male rising approximately 30 m and then carrying out a high-speed swooping dive over the female.3

Overall C. anna can produce a variety of noises, such as a chip note, a chatter, a song, and a sonation from diving. The chip note is described as a low-intensity “short, sharp, dry, ‘tzin’”1 which represents basic interaction amongst all members. The chatter resembles buzzy, harsh, high-intensity notes to signify aggression1, often given by territorial males or females guarding their nest. The song produced by C. anna is highly complex and structured. Males rely heavily on their song in breeding territories.1

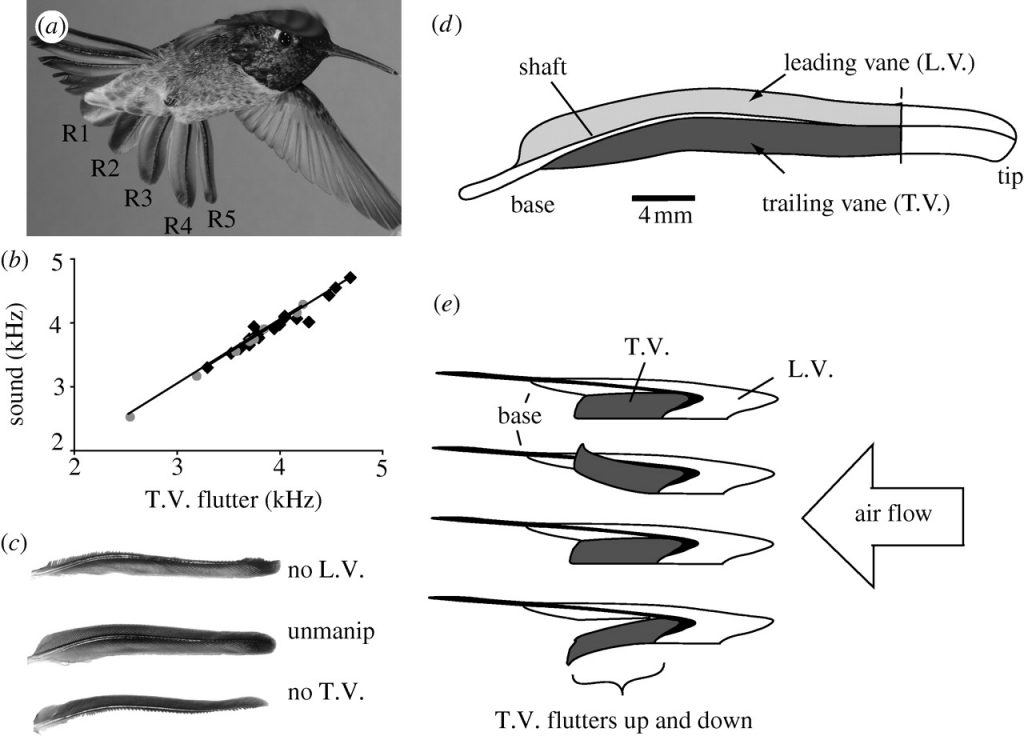

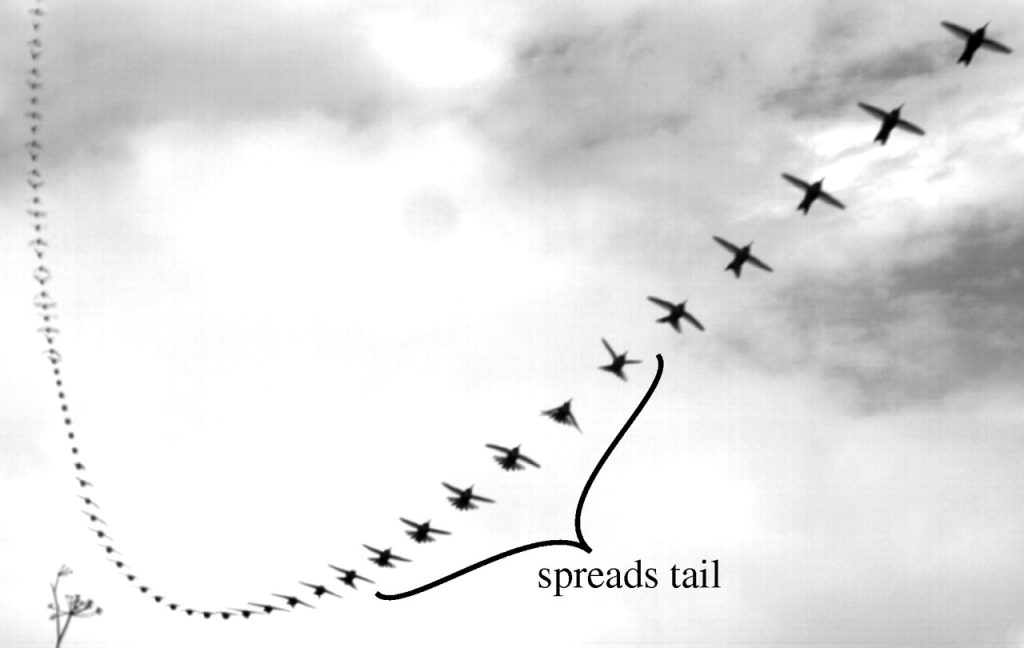

The chip, chatter and song all rely on vocal mechanisms from the syrinx. It was once thought that the sound created from the dive display was vocal as well, however through multiple studies2,3 with the use of high-speed video it has been proven the sound is a mechanism of the outermost tail feathers.2 The dive was analyzed extensively and split into 5 stages.2 The first stage begins with the hummingbird diving with a trajectory towards the sun. The diving male will propel himself downwards with wings flapping at a frequency of approximately 55.5 ± 1.72 Hz. In stage 2 the male ceases the flapping and tucks in his wings. In stage 3 the wings are spread to glide, transitioning into stage 4 in which the male reaches the bottom of the dive and will swiftly spread his tail, achieving the diving sonation. The final stage of the dive involves the male flapping his wings once and shutting the tail.

An illustration showing the location of the outer R5 feather on a male Anna’s. [Link]

Watch this video to hear the sound the tail feathers make when diving! [Link]

It’s been shown that C. anna can vocally produce a sound of the nearly the same frequency of their diving sonation.2 So why do these birds produce sound through their tail when they could produce an acoustically similar sound vocally? Phylogenetic reconstruction studies4 suggests that the diving sonation is ancestral and vocal song form evolved to mimic the dive-sounds. However, the function of the dive beyond impressing females is unclear, as is the chirping mechanism that results.

In performing this dive displays, hummingbirds reach an average maximum velocity of 27.3 ms-1, which is highest length-specific velocity performed by any vertebrate.2 It’s been hypothesized by Clark2 that hummingbirds reach these extreme speeds as a element of courtship display. The females sexual selection for high motor skills is the likely reasoning for hummingbirds executing these dives at their maximum performance limit.5 Another explanation suggests that an increase in dive speed results may be correlated to the sound amplitude produced by the tail feathers, and that females are likely selected to be able to discern these slight differences.5

An illustration of the tail feathers opening during the rapid dive. [Link]

Overall, hummingbirds truly have some unique adaptations, from their courtship displays, to their hovering flight. I hope you enjoyed reading about them today!

Literature cited:

1. Stiles, F. G. Aggressive and Courtship Displays of the Male Anna’s Hummingbird. Condor. [Online] 1982, 84 (2), 208 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1367674?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents (accessed Oct 12, 2017).

2. Clark, C. J. Courtship Dives of Anna’s Hummingbird Offer Insights into Flight Performance Limits. P. R. SOC. B.[Online] 2009, 276 (1670), 3047-3052 http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2009/06/05/rspb.2009.0508.short (accessed Oct 12, 2017).

3. Clark, C. J.; Feo, T. J. The Anna’s Hummingbird Chirps with its Tail: A New Mechanism of Sonation in Birds. P. R. SOC. B. [Online] 2008, 275 (1637), 955-962 http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/275/1637/955.short (accessed Oct 12, 2017).

4. Clark, C. J.; Feo, T. J. Why do Calypte Hummingbirds “Sing” with Both Their Tail and Their Syrinx? An Apparent Example of Sexual Sensory Bias. The American Naturalist [Online] 2009, 175 (1), 27-37 http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.viu.ca/stable/pdf/10.1086/648560.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ae14adb349bb8d821471e197033863e35 (accessed Oct 12, 2017).

5. Byers, J.; Hebets, E.; Podos, J. Female Mate Choice Based Upon Male Motor Performance. Animal Behaviour. [Online] 2010, 79 (4), 771-778 http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.viu.ca/science/article/pii/S0003347210000308 (accessed Oct 12, 2017).

6. Tamm, S.; Armstrong, D. P.; Tooze, Z. J. Display Behavior of Male Calliope Hummingbirds During the Breeding Season. Condor. [Online] 1989, 91 (2), 272 http://www.jstor.org/stable/1368304?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents (accessed Oct 12, 2017).

I found it really interesting how the R5 feather controls the sound production! The way they move still blows my mind. A question about territories; since these guys don’t migrate, do the males try and protect the same location year after year? And are they constantly defending it throughout the year or does it intensify in the spring (breeding only?)?

Thanks for the feedback Christina! That’s a great question. From what I’ve read, and from my own experience watching my hummingbird feeders, it’s very possible that these birds defend the same territory for years. Anna’s are extremely territorial, not only regarding mating but also their food source. It appears that male Anna’s are aggressively territorial all year to protect their food source and female Anna’s are more aggressive in protecting their nests. Therefore, I would say that territorial defence is only intensified in females when they are caring for their brood!